Tax Stimulus Options in the Aftermath of the Terrorist Attack

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Executive Branch

EXECUTIVE BRANCH THE PRESIDENT BARACK H. OBAMA, Senator from Illinois and 44th President of the United States; born in Honolulu, Hawaii, August 4, 1961; received a B.A. in 1983 from Columbia University, New York City; worked as a community organizer in Chicago, IL; studied law at Harvard University, where he became the first African American president of the Harvard Law Review, and received a J.D. in 1991; practiced law in Chicago, IL; lecturer on constitutional law, University of Chicago; member, Illinois State Senate, 1997–2004; elected as a Democrat to the U.S. Senate in 2004; and served from January 3, 2005, to November 16, 2008, when he resigned from office, having been elected President; family: married to Michelle; two children: Malia and Sasha; elected as President of the United States on November 4, 2008, and took the oath of office on January 20, 2009. EXECUTIVE OFFICE OF THE PRESIDENT 1600 Pennsylvania Avenue, NW., 20500 Eisenhower Executive Office Building (EEOB), 17th Street and Pennsylvania Avenue, NW., 20500, phone (202) 456–1414, http://www.whitehouse.gov The President of the United States.—Barack H. Obama. Special Assistant to the President and Personal Aide to the President.— Anita Decker Breckenridge. Director of Oval Office Operations.—Brian Mosteller. OFFICE OF THE VICE PRESIDENT phone (202) 456–1414 The Vice President.—Joseph R. Biden, Jr. Assistant to the President and Chief of Staff to the Vice President.—Bruce Reed, EEOB, room 276, 456–9000. Deputy Assistant to the President and Chief of Staff to Dr. Jill Biden.—Sheila Nix, EEOB, room 200, 456–7458. -

President Obama's Two War Inheritance

Journal of Military and Strategic Studies, Fall and Winter 2008/9, Vol. 11, Issues 1 and 2. CONFRONTING REALITY: PRESIDENT OBAMA’S TWO WAR INHERITANCE Terry Terriff, Arthur J. Child Chair of American Security Policy, Department of Political Science, University of Calgary On 20 January 2008 Barak Obama enters the White House to face a wide array of very daunting domestic and foreign challenges. Domestically, he is confronted with a dire situation: a financial meltdown, a US economy sinking ever deeper into recession, rapidly rising unemployment, a housing market in near free fall, dysfunctional health- care, energy and infrastructure systems, and a budget deficit which looks to exceed a trillion dollars. Internationally, he assumes responsibility for two land wars, a global struggle against Islamist terrorist elements, the prospect of nuclear-armed rogue states (especially Iran), diminishing American influence and power, an international financial system in crisis, and, very recently, the intense fighting between Israel and Hamas in Gaza, among a range of other security issues. Obama’s world is one full of problems and troubles. Obama’s activity during the transition period strongly suggests that his priority will be domestic problems rather than international issues. While he has remained relatively muted during the transition on international events such as the Mumbai terror attacks and the ongoing fighting between Israel- Hamas in Gaza, he has been very publicly active as President-elect in efforts to develop a massive stimulus package to be ready to sign as soon as possible after he assumes office. Reports on the stimulus plan make clear that Obama intends it to energize job creation through infrastructure investment, restore public confidence in the American economic system, kick-start a ©Centre for Military and Strategic Studies, 2009. -

Tax Policy— Unfinished Business

37th Annual Spring Symposium and State-Local Tax Program Tax Policy— Unfinished Business Tangle of Taxes Health Policy Tax Policy and Retirement Issues in Corporate Taxation Tax Compliance Thoughts for the New Congress The Role of Federal and State Federal Impact on State Spending May 17–18, 2007 Holiday Inn Capitol Washington DC REGISTRATION — Columbia Foyer President Thursday, May 17, 8:00 AM - 4:00 PM Robert Tannenwald Friday, May 18, 8:00 AM - 12:30 PM Program Chair All sessions will meet in the COLUMBIA BALLROOM Thomas Woodward Executive Director J. Fred Giertz Thursday, May 17 8:45–9:00 AM WELCOME AND INTRODUCTION 9:00–10:30 AM ROUNDTABLE: RICHARD MUSGRAVE REMEMBERED Organizer: Diane Lim Rogers, Committee on the Budget, U.S. House of Representatives Moderator: Henry Aaron, The Brookings Institution Discussants: Helen Ladd, Duke University; Wallace Oates, University of Maryland ; Joel Slemrod, University of Michigan 10:30–10:45 AM BREAK 10:45–12:15 PM TANGLES OF TAXES: PROBLEMS IN THE TAX CODE Organizer/Moderator: Roberton Williams Jr., Urban-Brookings Tax Policy Center Alex Brill, American Enterprise Institute — The Individual Income Tax After 2010: Post-Permanencism Ellen Harrison, Winthrop Shaw Pittman LLP — Estate Planning Under the Bush Tax Cuts Leonard Burman, William Gale, Gregory Leiserson, and Jeffery Rohaly, Urban-Brookings Tax Policy Center — The AMT: What’s Wrong and How to Fix It Discussants: Roberta Mann, Widener University School of Law; David Weiner, Congressional Budget Office 12:30–1:45 PM LUNCHEON - DISCOVERY BALLROOM Speaker: Peter Orszag, Director, Congressional Budget Office Presentation of Davie-Davis Award for Public Service 2:00–3:30 PM HEALTH POLICY: THE ROLE FOR TAXES Organizer: Timothy Dowd, Joint Committee on Taxation Moderator: Alexandra Minicozzi, Office of Tax Analysis, U.S. -

Brief of Amici Curiae Bipartisan Economic Scholars

No. 19-840 In the Supreme Court of the United States _________ CALIFORNIA, ET AL., Petitioners, v. TEXAS, ET AL., Respondents. _________ On Writ of Certiorari to the United States Court of Appeals for the Fifth Circuit _________ BRIEF AMICI CURIAE FOR BIPARTISAN ECONOMIC SCHOLARS IN SUPPORT OF PETITIONERS _________ SHANNA H. RIFKIN MATTHEW S. HELLMAN JENNER & BLOCK LLP Counsel of Record 353 N. Clark Street JENNER & BLOCK LLP Chicago, IL 60654 1099 New York Avenue, NW Washington, DC 20001 (202) 639-6000 May 13, 2020 [email protected] i TABLE OF CONTENTS TABLE OF AUTHORITIES ......................................... iii INTEREST OF AMICI CURIAE .................................. 1 INTRODUCTION AND SUMMARY OF ARGUMENT ....................................................................... 3 ARGUMENT ....................................................................... 5 I. The Fifth Circuit’s Severability Analysis Lacks Any Economic Foundation And Would Cause Egregious Harm To Those Currently Enrolled In Medicaid And Private Individual Market Insurance As Well As Health Care Providers. ....................................................................... 5 A. Economic Data Establish That The ACA Markets Can Operate Without The Mandate. ................................................................... 5 B. There Is No Economic Reason Why Congress Would Have Wanted The Myriad Other Provisions In The ACA To Be Invalidated. ....................................................... 10 II. Because The ACA Can Operate Effectively Without -

HAMILTON Achieving Progressive Tax Reform PROJECT in an Increasingly Global Economy Strategy Paper JUNE 2007 Jason Furman, Lawrence H

THE HAMILTON Achieving Progressive Tax Reform PROJECT in an Increasingly Global Economy STRATEGY PAPER JUNE 2007 Jason Furman, Lawrence H. Summers, and Jason Bordoff The Brookings Institution The Hamilton Project seeks to advance America’s promise of opportunity, prosperity, and growth. The Project’s economic strategy reflects a judgment that long-term prosperity is best achieved by making economic growth broad-based, by enhancing individual economic security, and by embracing a role for effective government in making needed public investments. Our strategy—strikingly different from the theories driving economic policy in recent years—calls for fiscal discipline and for increased public investment in key growth- enhancing areas. The Project will put forward innovative policy ideas from leading economic thinkers throughout the United States—ideas based on experience and evidence, not ideology and doctrine—to introduce new, sometimes controversial, policy options into the national debate with the goal of improving our country’s economic policy. The Project is named after Alexander Hamilton, the nation’s first treasury secretary, who laid the foundation for the modern American economy. Consistent with the guiding principles of the Project, Hamilton stood for sound fiscal policy, believed that broad-based opportunity for advancement would drive American economic growth, and recognized that “prudent aids and encouragements on the part of government” are necessary to enhance and guide market forces. THE Advancing Opportunity, HAMILTON Prosperity and Growth PROJECT Printed on recycled paper. THE HAMILTON PROJECT Achieving Progressive Tax Reform in an Increasingly Global Economy Jason Furman Lawrence H. Summers Jason Bordoff The Brookings Institution JUNE 2007 The views expressed in this strategy paper are those of the authors and are not necessarily those of The Hamilton Project Advisory Council or the trustees, officers, or staff members of the Brookings Institution. -

Executive Branch

EXECUTIVE BRANCH THE PRESIDENT BARACK H. OBAMA, Senator from Illinois and 44th President of the United States; born in Honolulu, Hawaii, August 4, 1961; received a B.A. in 1983 from Columbia University, New York City; worked as a community organizer in Chicago, IL; studied law at Harvard University, where he became the first African American president of the Harvard Law Review, and received a J.D. in 1991; practiced law in Chicago, IL; lecturer on constitutional law, University of Chicago; member, Illinois State Senate, 1997–2004; elected as a Democrat to the U.S. Senate in 2004; and served from January 3, 2005, to November 16, 2008, when he resigned from office, having been elected President; family: married to Michelle; two children: Malia and Sasha; elected as President of the United States on November 4, 2008, and took the oath of office on January 20, 2009. EXECUTIVE OFFICE OF THE PRESIDENT 1600 Pennsylvania Avenue, NW., 20500 Eisenhower Executive Office Building (EEOB), 17th Street and Pennsylvania Avenue, NW., 20500, phone (202) 456–1414, http://www.whitehouse.gov The President of the United States.—Barack H. Obama. Personal Aide to the President.—Katherine Johnson. Special Assistant to the President and Personal Aide.—Reginald Love. OFFICE OF THE VICE PRESIDENT phone (202) 456–1414 The Vice President.—Joseph R. Biden, Jr. Chief of Staff to the Vice President.—Bruce Reed, EEOB, room 202, 456–9000. Deputy Chief of Staff to the Vice President.—Alan Hoffman, EEOB, room 202, 456–9000. Counsel to the Vice President.—Cynthia Hogan, EEOB, room 246, 456–3241. -

Lion in Winter

NESI 1 LION IN WINTER: EDWARD M. KENNEDY IN THE BUSH YEARS A STUDY IN SENATE LEADERSHIP BY Edward A. Nesi A Study Presented to the Faculty of Wheaton College in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for Graduation with Departmental Honors in Political Science Norton, Massachusetts May 19, 2007 NESI 2 For mom who taught me the value of empathy and to value it in others NESI 3 Table of Contents I. Introduction 4 II. What Makes a Senate Leader? 13 III. No Child Left Behind: The Conciliatory Kennedy 53 IV. Iraq: The Oppositional Kennedy 95 V. Conclusion 176 Bibliography 186 NESI 4 I. Introduction “[I]n the arrogance of our conviction that we would have done better than he did in a single case, we exempt ourselves from any duty to pay attention to the many cases where he shows himself to be better than us.” 1 — Murray Kempton, New York Newsday , November 27, 1983 EDWARD MOORE KENNEDY AND I share the same first name; we also share the somewhat uncommon nickname of Ted for Edward. And for the first two decades of my life, that was roughly the extent of my knowledge about the man who has been my state’s senior senator for my entire life, all but seven years of my mother’s life, and more than half of my grandmother’s life. Kennedy has been a member of the Senate for so long (45 of his 75 years) that it seems he could have been born in the cloakroom, though he was actually born in Boston on February 22, 1932, the youngest child of Joseph Patrick and Rose Fitzgerald Kennedy. -

Executive Branch

EXECUTIVE BRANCH THE PRESIDENT BARACK H. OBAMA, Senator from Illinois and 44th President of the United States; born in Honolulu, Hawaii, August 4, 1961; received a B.A. in 1983 from Columbia University, New York City; worked as a community organizer in Chicago, IL; studied law at Harvard University, where he became the first African American president of the Harvard Law Review, and received a J.D. in 1991; practiced law in Chicago, IL; lecturer on constitutional law, University of Chicago; member, Illinois State Senate, 1997–2004; elected as a Democrat to the U.S. Senate in 2004; and served from January 3, 2005, to November 16, 2008, when he resigned from office, having been elected President; family: married to Michelle; two children: Malia and Sasha; elected as President of the United States on November 4, 2008, and took the oath of office on January 20, 2009. EXECUTIVE OFFICE OF THE PRESIDENT 1600 Pennsylvania Avenue, NW., 20500 Eisenhower Executive Office Building (EEOB), 17th Street and Pennsylvania Avenue, NW., 20500, phone (202) 456–1414, http://www.whitehouse.gov The President of the United States.—Barack H. Obama. Personal Aide to the President.—Katherine Johnson. Special Assistant to the President and Personal Aide.—Reginald Love. OFFICE OF THE VICE PRESIDENT phone (202) 456–1414 The Vice President.—Joseph R. Biden, Jr. Chief of Staff to the Vice President.—Bruce Reed, EEOB, room 202, 456–9000. Deputy Chief of Staff to the Vice President.—Alan Hoffman, EEOB, room 202, 456–9000. Counsel to the Vice President.—Cynthia Hogan, EEOB, room 246, 456–3241. -

Office of Government Ethics

UNITED STATES OFFICE OF GOVERNMENT ETHICS Preventing Conflicts* of Interest in the Executive Branch ANNUAL REPORT PURSUANT TO EXECUTIVE ORDER 13490 ETHICS COMMITMENTS BY EXECUTIVE BRANCH PERSONNEL JANUARY 1, 2011 - DECEMBER 31, 2011 'fable of Contents Preface . ... ...... ....... ........ .... .. ... .... ......... .. ... ... ....... .. ... ........... ... .... 2 Ethics Pledge Compliance.. ..... ... ... .. ..... ... .. ..... ... .......... ...... ... .. .. .. 3 Table 1: Full-Time, Non-Career Appointees ............................................. 4 Table 2: Ethics Pledge Signatures (by Appointee Type) .............. .. ......... ..... 5 Table 3: Appointees Not Required to Sign th e Ethics Pledge in 2011 ............... 5 Table 4: 2011 Appointees who Received Paragraph 2 Waivers.. ...... .. .... .. ..... 7 Enforcement. .. .. .. .. ... .......... ..... .... .... ... ...... .. .. .. ... ... .. ..... ... .. .... 7 Implementation of the Lobbyist Gift Ban............................ ........ ....... ... 7 Appendix I Executive Order 13490 Appendix II Assessment Methodology Appendix III Assessment Questionnaire Appendix IV Pledge Paragraph 2 Waivers Preface Thi s is the third annual report provided pursuant to the President's Executive Order on Ethics (Executive Order 13490 of Janu ary 2 1, 2009, "Ethics Commitments by Executive Branch Personnel"). This report provides information on: th e number of full-time, non-career appo intees who were appointed during the 20 11 ca lendar year; the appointees who were req uired to sign th e Ethics Pledge; the number and nam es of th ose appointees who rece ived waivers of any Ethi cs Pledge provisions; and, where appropriate, recusals or ethics agreements for those appointees who were registered lobb yists within the two years prior to their appointment. The repo rt covers th e time period January I through December 3 1, 201 1. This report is publicly availab le. It has been posted on the United Stat es Office of Government Ethics ' (OGE) website at \V \V\V . -

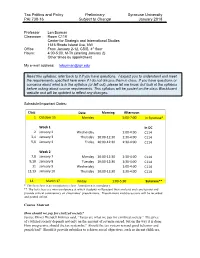

Notes for Tax Policy Course

Tax Politics and Policy Preliminary Syracuse University PAI 730-16 Subject to Change January 2018 Professor Len Burman Classroom Room C119 Center for Strategic and International Studies 1616 Rhode Island Ave, NW Office From January 2-12, CSIS, 4th floor Hours: 4:00-5:00, M-Th (starting January 2) Other times by appointment My e-mail address: [email protected] Read this syllabus; refer back to it if you have questions. I expect you to understand and meet the requirements specified here even if I do not discuss them in class. If you have questions or concerns about what is in the syllabus (or left out), please let me know, but look at the syllabus before asking about course requirements. This syllabus will be posted on the class Blackboard website and will be updated to reflect any changes. Schedule/Important Dates: Class Date Morning Afternoon 1 October 15 Monday 5:00-7:00 In Syracuse* Week 1 In DC 2 January 2 Wednesday 1:00-4:00 C114 3,4 January 3 Thursday 10:00-12:30 1:30-4:00 C114 5,6 January 4 Friday 10:00-12:30 1:30-4:00 C114 Week 2 7,8 January 7 Monday 10:00-12:30 1:30-4:00 C114 9,10 January 8 Tuesday 10:00-12:30 1:30-4:00 C114 11 January 9 Wednesday 1:00-4:00 C114 12,13 January 10 Thursday 10:00-12:30 1:30-4:00 C114 14 March 1? Friday 1:00-5:30 Syracuse** * The first class is an introductory class. -

House Passes Health-Care Reform Bill Without Republican Votes Page 1 of 6

House passes health-care reform bill without Republican votes Page 1 of 6 House passes health-care reform bill without Republican votes By Shailagh Murray and Lori Montgomery approved the bill, which first passed the Washington Post Staff Writers Senate on Christmas Eve. Monday, March 22, 2010; A01 The debate has consumed Obama's first House Democrats scored a historic victory year in office, with his focus on the issue in the century-long battle to reform the amid a deep recession and crippling job nation's health-care system late Sunday losses potentially endangering his night, winning final approval of reelection prospects and Democratic legislation that expands coverage to 32 majorities in the House and the Senate. It million people and attempts to contain has inflamed the partisanship that spiraling costs. Obama pledged to tame when he campaigned for the White House and has The House voted 219 to 212 to approve limited Congress's ability to pass any the measure, with every Republican other major legislation, at least until voting no. The measure now awaits after the midterm elections in November. President Obama's signature. In remarks Sunday night, he said that the vote And it has sparked a citizens' revolt that "proved that we are still capable of doing reached the doors of the Capitol this big things. We proved that this weekend. government -- a government of the people and by the people -- still works "If we pass this bill, there will be no for the people." turning back," House Minority Leader House Speaker Nancy Pelosi and her Advertisement colleagues erupted in cheers and hugs as the votes were counted, while Republicans who had fought the Democratic efforts on health-care reform for more than a year appeared despondent. -

The Sunday Fix for Even More of the Fix Go to Washingtonpost.Com/Thefix

2BLACK A2 DAILY 01-20-08 MD RE A2 BLACK A2 Sunday, January 20, 2008 R The Washington Post ON WASHINGTONPOST.COM The Sunday Fix For even more of the Fix go to washingtonpost.com/thefix CHRIS CILLIZZA AND SHAILAGH MURRAY It’s Never Too Early to Think About No. 2 Here at the Sunday Fix, we’re already looking beyond the nomination fi ghts to the always entertaining vice presidential speculation game. We queried some party strategists for their thoughts on the early front-runners. Here’s their consensus: DEMOCRATS John Edwards Tim Kaine Wesley Clark Tom Daschle Evan Bayh Kathleen Sebelius Tom Vilsack The former senator from The popular Virginia Clark, who ran for presi- He and his political in- The senator from Indiana The two-term Kansas Going into the Iowa cau- North Carolina has done governor was one of the dent in 2004, has been ner circle are extremely is clearly angling for the governor is a rising star cuses, Vilsack was the it once, so most peo- first to endorse Sen. one of the most valu- close to Obama. Daschle No. 2 slot, with his early nationally and is coming leader in the clubhouse ple think he won’t do it Barack Obama (Ill.). able surrogates of Sen. would help Obama ad- endorsement and strong off a successful stint as for vice president if Clin- again. If Edwards stays Kaine comes from a Hillary Rodham Clinton dress questions about advocacy for Clinton. He chairman of the Demo- ton were to win the nom- in through the conven- swing state, is term- (N.Y.).