Brief of Amici Curiae Bipartisan Economic Scholars

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Tax Policy— Unfinished Business

37th Annual Spring Symposium and State-Local Tax Program Tax Policy— Unfinished Business Tangle of Taxes Health Policy Tax Policy and Retirement Issues in Corporate Taxation Tax Compliance Thoughts for the New Congress The Role of Federal and State Federal Impact on State Spending May 17–18, 2007 Holiday Inn Capitol Washington DC REGISTRATION — Columbia Foyer President Thursday, May 17, 8:00 AM - 4:00 PM Robert Tannenwald Friday, May 18, 8:00 AM - 12:30 PM Program Chair All sessions will meet in the COLUMBIA BALLROOM Thomas Woodward Executive Director J. Fred Giertz Thursday, May 17 8:45–9:00 AM WELCOME AND INTRODUCTION 9:00–10:30 AM ROUNDTABLE: RICHARD MUSGRAVE REMEMBERED Organizer: Diane Lim Rogers, Committee on the Budget, U.S. House of Representatives Moderator: Henry Aaron, The Brookings Institution Discussants: Helen Ladd, Duke University; Wallace Oates, University of Maryland ; Joel Slemrod, University of Michigan 10:30–10:45 AM BREAK 10:45–12:15 PM TANGLES OF TAXES: PROBLEMS IN THE TAX CODE Organizer/Moderator: Roberton Williams Jr., Urban-Brookings Tax Policy Center Alex Brill, American Enterprise Institute — The Individual Income Tax After 2010: Post-Permanencism Ellen Harrison, Winthrop Shaw Pittman LLP — Estate Planning Under the Bush Tax Cuts Leonard Burman, William Gale, Gregory Leiserson, and Jeffery Rohaly, Urban-Brookings Tax Policy Center — The AMT: What’s Wrong and How to Fix It Discussants: Roberta Mann, Widener University School of Law; David Weiner, Congressional Budget Office 12:30–1:45 PM LUNCHEON - DISCOVERY BALLROOM Speaker: Peter Orszag, Director, Congressional Budget Office Presentation of Davie-Davis Award for Public Service 2:00–3:30 PM HEALTH POLICY: THE ROLE FOR TAXES Organizer: Timothy Dowd, Joint Committee on Taxation Moderator: Alexandra Minicozzi, Office of Tax Analysis, U.S. -

HAMILTON Achieving Progressive Tax Reform PROJECT in an Increasingly Global Economy Strategy Paper JUNE 2007 Jason Furman, Lawrence H

THE HAMILTON Achieving Progressive Tax Reform PROJECT in an Increasingly Global Economy STRATEGY PAPER JUNE 2007 Jason Furman, Lawrence H. Summers, and Jason Bordoff The Brookings Institution The Hamilton Project seeks to advance America’s promise of opportunity, prosperity, and growth. The Project’s economic strategy reflects a judgment that long-term prosperity is best achieved by making economic growth broad-based, by enhancing individual economic security, and by embracing a role for effective government in making needed public investments. Our strategy—strikingly different from the theories driving economic policy in recent years—calls for fiscal discipline and for increased public investment in key growth- enhancing areas. The Project will put forward innovative policy ideas from leading economic thinkers throughout the United States—ideas based on experience and evidence, not ideology and doctrine—to introduce new, sometimes controversial, policy options into the national debate with the goal of improving our country’s economic policy. The Project is named after Alexander Hamilton, the nation’s first treasury secretary, who laid the foundation for the modern American economy. Consistent with the guiding principles of the Project, Hamilton stood for sound fiscal policy, believed that broad-based opportunity for advancement would drive American economic growth, and recognized that “prudent aids and encouragements on the part of government” are necessary to enhance and guide market forces. THE Advancing Opportunity, HAMILTON Prosperity and Growth PROJECT Printed on recycled paper. THE HAMILTON PROJECT Achieving Progressive Tax Reform in an Increasingly Global Economy Jason Furman Lawrence H. Summers Jason Bordoff The Brookings Institution JUNE 2007 The views expressed in this strategy paper are those of the authors and are not necessarily those of The Hamilton Project Advisory Council or the trustees, officers, or staff members of the Brookings Institution. -

Tax Stimulus Options in the Aftermath of the Terrorist Attack

TAX STIMULUS OPTIONS IN THE AFTERMATH OF THE TERRORIST ATTACK By William Gale, Peter Orszag, and Gene Sperling William Gale is the Joseph A. Pechman Senior outlook thus suggests the need for policies that Fellow in Economic Studies at the Brookings Institu- stimulate the economy in the short run. The budget tion. Peter Orszag is Senior Fellow in Economic outlook suggests that the long-run revenue impact Studies at the Brookings Institution. Gene Sperling is of stimulus policies should be limited, so as to avoid Visiting Fellow in Economic Studies at the Brookings exacerbating the nation’s long-term fiscal challen- Institution, and served as chief economic adviser to ges, which would raise interest rates and undermine President Clinton. The authors thank Henry Aaron, the effectiveness of the stimulus. Michael Armacost, Alan Auerbach, Leonard Burman, In short, say the authors, the most effective Christopher Carroll, Robert Cumby, Al Davis, Eric stimulus package would be temporary and maxi- Engen, Joel Friedman, Jane Gravelle, Robert mize its “bang for the buck.” It would direct the Greenstein, Richard Kogan, Iris Lav, Alice Rivlin, Joel largest share of its tax cuts toward spurring new Slemrod, and Jonathan Talisman for helpful discus- economic activity, and it would minimize long-term sions. The opinions expressed represent those of the revenue losses. This reasoning suggests five prin- authors and should not be attributed to the staff, of- ciples for designing the most effective tax stimulus ficers, or trustees of the Brookings Institution. package: (1) Allow only temporary, not permanent, In the aftermath of the recent terrorist attacks, the items. -

Notes for Tax Policy Course

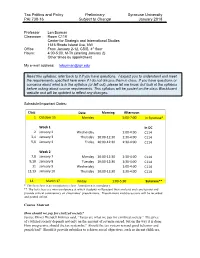

Tax Politics and Policy Preliminary Syracuse University PAI 730-16 Subject to Change January 2018 Professor Len Burman Classroom Room C119 Center for Strategic and International Studies 1616 Rhode Island Ave, NW Office From January 2-12, CSIS, 4th floor Hours: 4:00-5:00, M-Th (starting January 2) Other times by appointment My e-mail address: [email protected] Read this syllabus; refer back to it if you have questions. I expect you to understand and meet the requirements specified here even if I do not discuss them in class. If you have questions or concerns about what is in the syllabus (or left out), please let me know, but look at the syllabus before asking about course requirements. This syllabus will be posted on the class Blackboard website and will be updated to reflect any changes. Schedule/Important Dates: Class Date Morning Afternoon 1 October 15 Monday 5:00-7:00 In Syracuse* Week 1 In DC 2 January 2 Wednesday 1:00-4:00 C114 3,4 January 3 Thursday 10:00-12:30 1:30-4:00 C114 5,6 January 4 Friday 10:00-12:30 1:30-4:00 C114 Week 2 7,8 January 7 Monday 10:00-12:30 1:30-4:00 C114 9,10 January 8 Tuesday 10:00-12:30 1:30-4:00 C114 11 January 9 Wednesday 1:00-4:00 C114 12,13 January 10 Thursday 10:00-12:30 1:30-4:00 C114 14 March 1? Friday 1:00-5:30 Syracuse** * The first class is an introductory class. -

HAMILTON an Economic Strategy for PROJECT Investing in America’S Infrastructure Strategy Paper Manasi Deshpande and Douglas W

THE HAMILTON An Economic Strategy for PROJECT Investing in America’s Infrastructure STRATEGY PAPER Manasi Deshpande and Douglas W. Elmendorf JULY 2008 The Hamilton Project seeks to advance America’s promise of opportunity, prosperity, and growth. The Project’s economic strategy reflects a judgment that long-term prosperity is best achieved by making economic growth broad-based, by enhancing individual economic security, and by embracing a role for effective government in making needed public investments. Our strategy—strikingly different from the theories driving economic policy in recent years—calls for fiscal discipline and for increased public investment in key growth- enhancing areas. The Project will put forward innovative policy ideas from leading economic thinkers throughout the United States—ideas based on experience and evidence, not ideology and doctrine—to introduce new, sometimes controversial, policy options into the national debate with the goal of improving our country’s economic policy. The Project is named after Alexander Hamilton, the nation’s first treasury secretary, who laid the foundation for the modern American economy. Consistent with the guiding principles of the Project, Hamilton stood for sound fiscal policy, believed that broad-based opportunity for advancement would drive American economic growth, and recognized that “prudent aids and encouragements on the part of government” are necessary to enhance and guide market forces. THE Advancing Opportunity, HAMILTON Prosperity and Growth PROJECT Printed on recycled paper. THE HAMILTON PROJECT An Economic Strategy for Investing in America’s Infrastructure Manasi Deshpande Douglas W. Elmendorf JULY 2008 Abstract Infrastructure investment has received more attention in recent years because of increased delays from road and air congestion, high-profile infrastructure failures, and rising concerns about energy security and climate change. -

Department of the Treasury Internal Revenue Service

Department of the Treasury Internal Revenue Service Mark W. Everson Commissioner Mark J. Mazur Director, Research, Analysis, and Statistics Janice M. Hedemann Director, Office of Research IRS Research Bulletin Recent Research on Tax Administration and Compliance Selected Papers Given at the 2006 IRS Research Conference Georgetown University School of Law Washington, DC June 14-15, 2006 Compiled and Edited by James Dalton and Beth Kilss* Statistics of Income Division Internal Revenue Service *Prepared under the direction of Janet McCubbin, Chief, Special Studies Branch IRS Research Bulletin iii Foreword This edition of the IRS Research Bulletin (Publication 1500) features selected papers from the latest IRS Research Conference, held at the Georgetown Uni- versity School of Law in Washington, DC, on June 14-15, 2006. Conference presenters and attendees included researchers from all areas of IRS, represen- tatives of other government agencies (including from the United Kingdom, Australia, and New Zealand), and academic and private sector experts on tax policy, tax administration, and tax compliance. The conference began with a keynote address by Mark Matthews, Deputy Commissioner for Services and Enforcement. Mr. Matthews emphasized the importance of using high-quality data and analysis to drive key decisions. Mark Mazur, Director, Research, Analysis and Statistics, then led a panel discus- sion on compliance and administrative aspects of tax reform. The panelists, including former Assistant Secretaries for Tax Policy Pamela Olson and Ronald Pearlman, former Deputy Assistant Secretary for Tax Analysis Leonard Burman, and Jane Gravelle of the Congressional Research Service, emphasized the need to use data and analysis to inform policies as they are first being formulated, rather than after positions have hardened. -

H.R. 1872, Budget and Accounting Transparency Act of 2014

1 113TH CONGRESS " ! REPT. 113–381 2d Session HOUSE OF REPRESENTATIVES Part 1 H.R. 1872, BUDGET AND ACCOUNTING TRANSPARENCY ACT OF 2014 R E P O R T OF THE COMMITTEE ON THE BUDGET HOUSE OF REPRESENTATIVES TO ACCOMPANY H.R. 1872 together with MINORITY VIEWS MARCH 18, 2014.—Committed to the Committee of the Whole House on the State of the Union and ordered to be printed U.S. GOVERNMENT PRINTING OFFICE 39–006 WASHINGTON : 2014 VerDate Mar 15 2010 02:45 Mar 19, 2014 Jkt 039006 PO 00000 Frm 00001 Fmt 4012 Sfmt 4012 E:\HR\OC\HR381P1.XXX HR381P1 tjames on DSK6SPTVN1PROD with REPORTS seneagle COMMITTEE ON THE BUDGET PAUL RYAN, Wisconsin, Chairman TOM PRICE, Georgia CHRIS VAN HOLLEN, Maryland, SCOTT GARRETT, New Jersey Ranking Minority Member JOHN CAMPBELL, California ALLYSON Y. SCHWARTZ, Pennsylvania KEN CALVERT, California JOHN A. YARMUTH, Kentucky TOM COLE, Oklahoma BILL PASCRELL, JR., New Jersey TOM MCCLINTOCK, California TIM RYAN, Ohio JAMES LANKFORD, Oklahoma GWEN MOORE, Wisconsin DIANE BLACK, Tennessee KATHY CASTOR, Florida REID J. RIBBLE, Wisconsin JIM MCDERMOTT, Washington BILL FLORES, Texas BARBARA LEE, California TODD ROKITA, Indiana HAKEEM S. JEFFRIES, New York ROB WOODALL, Georgia MARK POCAN, Wisconsin MARSHA BLACKBURN, Tennessee MICHELLE LUJAN GRISHAM, New Mexico ALAN NUNNELEE, Mississippi JARED HUFFMAN, California E. SCOTT RIGELL, Virginia TONY CA´ RDENAS, California VICKY HARTZLER, Missouri EARL BLUMENAUER, Oregon JACKIE WALORSKI, Indiana KURT SCHRADER, Oregon LUKE MESSER, Indiana [Vacant] TOM RICE, South Carolina ROGER WILLIAMS, Texas SEAN P. DUFFY, Wisconsin PROFESSIONAL STAFF AUSTIN SMYTHE, Staff Director THOMAS S. KAHN, Minority Staff Director (II) VerDate Mar 15 2010 01:51 Mar 19, 2014 Jkt 039006 PO 00000 Frm 00002 Fmt 5904 Sfmt 5904 E:\HR\OC\HR381P1.XXX HR381P1 tjames on DSK6SPTVN1PROD with REPORTS C O N T E N T S Page H.R. -

The Urban–Brookings Tax Policy Center 2007 Annual Report

Cover-TPC-2007.indd 1 23.12.2007 21:00:23 The Urban–Brookings Tax Policy Center 2007 Annual Report The Urban Institute, 2100 M Street, N.W., Washington, DC 20037 The Brookings Institution, 1775 Massachusetts Ave., N.W., Washington, DC 20036 http://www.taxpolicycenter.org LETTER FROM THE DIRECTORS When we wrote our first proposals for the Tax Policy Center, we felt the compelling need for timely, high-quality, and comprehensible analysis of tax issues. Fortunately, we were able to convince a small group of generous foundations and individuals, but all of us— funders and researchers alike—wondered if the public would agree. It did. In five years, the Tax Policy Center has become an authority on tax issues. Hardly a day goes by when we’re not called by reporters, policy staffers (and sometimes policymakers themselves), or researchers at other think tanks or universities with tax policy questions. And with an enormous quantity of estimates and analysis on our web site, many others are able to find what they need by themselves. One indication that we’d arrived came in September when Senator Obama’s campaign asked if the Tax Policy Center would host a major speech on tax policy. This request by a major presidential candidate acknowledged our preeminence in taxes and validated everything we’d worked so hard to accomplish. (Of course, TPC is politically neutral and welcomes any major candidate who wishes to address our nation’s tax policy challenges.) From the beginning, we have worked hard to produce timely analysis of tax policy topics. -

Curriculum Vitae William G. Gale

Curriculum Vitae William G. Gale March 2019 Contact Information Address Brookings Institution 1775 Massachusetts Avenue, NW Washington, DC 20036-2188 Telephone (202) 797-6148 Fax (202) 797-6181 E-mail [email protected] Current Positions at Brookings 2007- Director, Retirement Security Project 2002- Co-Director and Co-Founder, Urban-Brookings Tax Policy Center 2001- Arjay and Frances Fearing Miller Chair in Federal Economic Policy 1994- Senior Fellow, Economic Studies Program Prior Employment 1992-present Brookings Institution 2006-2009 Vice President and Director, Economic Studies Program 2001-2006 Deputy Director, Economic Studies Program 1994-2001 Senior Fellow and Joseph A. Pechman Fellow 1992-1994 Research Associate and Joseph A. Pechman Fellow 1991-1992 Council of Economic Advisers, Senior Economist 1987-1991 UCLA, Assistant Professor, Department of Economics Education 1982-1987 Ph. D., Economics, Stanford University 1977-1981 A. B., Economics, Duke University. Magna Cum Laude 1979-1980 General Course Student, London School of Economics Professional Appointments and Honors (current, except where noted) 2018 Member, Advisory Board, EconoFact 2018 Second Vice President, National Tax Association 2017 Consultant to MSL Group 2017 Panelist, Center for Strategic Development, Kingdom of Saudi Arabia Economic Reforms Workshop 2017 2017 Ellen Bellet Goldberg Tax Policy Lecture, University of Florida 2016 Member, Macroeconomic Advisers Board of Advisors 1 2016 2016 Referee of the Year, National Tax Journal 2014-16 Commissioner, Retirement Security and Personal Savings Commission, Bipartisan Policy Center 2013-15 Consultant to Mayer, Brown, Rowe & Maw LLP 2011-12 Chair, Davie-Davies Committee, National Tax Association 2010-14 Member, Global Agenda Council on Fiscal Crises, World Economic Forum 2009-11 Co-Editor, The Economists’ Voice 2009 Chair, Spring Symposium, National Tax Association 2007 TIAA-CREF Paul A. -

Curriculum Vitae William G. Gale

Curriculum Vitae William G. Gale April 2015 Contact Information Address Brookings Institution 1775 Massachusetts Avenue, NW Washington, DC 20036-2188 Telephone (202) 797-6148 Fax (202) 797-6181 E-mail [email protected] Current Positions at Brookings 2007- Director, Retirement Security Project 2002- Co-Director, Urban-Brookings Tax Policy Center 2001- Arjay and Frances Fearing Miller Chair in Federal Economic Policy 1994- Senior Fellow, Economic Studies Program Prior Employment 1992-present Brookings Institution 2006-2009 Vice President and Director, Economic Studies Program 2001-2006 Deputy Director, Economic Studies Program 1994-2001 Senior Fellow and Joseph A. Pechman Fellow 1992-1994 Research Associate and Joseph A. Pechman Fellow 1991-1992 Council of Economic Advisers, Senior Economist 1987-1991 UCLA, Assistant Professor, Department of Economics Education 1982-1987 Ph. D., Economics, Stanford University 1977-1981 A. B., Economics, Duke University. Magna Cum Laude 1979-1980 General Course Student, London School of Economics Professional Appointments (current, except where noted) 2014- Commissioner, Retirement Security and Personal Savings Commission, Bipartisan Policy Center 2013- Consultant to Mayer Brown 2011-12 Chair, Davie-Davies Committee, National Tax Association 2010- Member, Global Agenda Council on Fiscal Crises, World Economic Forum 1 2009-11 Co-Editor, The Economists’ Voice 2009 Chair, Spring Symposium, National Tax Association 2007 TIAA-CREF Paul A. Samuelson Award Certificate of Excellence 2005-6 Consultant to Enterprise Rent-A-Car 2004-6 Consultant to Mayer, Brown, Rowe & Maw LLP 2004- Board of Directors, Center on Federal Financial Institutions 2004 Adviser, Tax Reform Project, Committee for Economic Development 2003- Research Advisory Council, SEED 2002 Advisory Panel on Dynamic Scoring, Joint Committee on Taxation. -

2005 Annual Report

The Urban–Brookings Tax Policy Center 2005 Annual Report Independent, timely, and accessible analyses of current and emerging tax policy issues The Urban Institute, 2100 M Street, NW, Washington, DC 20037 The Brookings Institution, 1775 Massachusetts Avenue, NW, Washington, DC 20036 http://www.taxpolicycenter.org CONTENTS OVERVIEW................................................................................................... 2 2005 HIGHLIGHTS ...................................................................................... 3 NEW PROGRAM ON STATE AND LOCAL TAXATION ....................... 5 MODEL ENHANCEMENTS........................................................................ 5 OUTREACH .................................................................................................. 6 FUNDRAISING............................................................................................. 8 KEY TPC PERSONNEL.............................................................................. 9 PUBLICATIONS, REPORTS, AND COMMENTARIES ....................... 14 TESTIMONIES ........................................................................................... 19 PUBLIC FORUMS...................................................................................... 20 REVENUE AND DISTRIBUTION TABLES............................................ 20 MEDIA PLACEMENT ................................................................................ 20 1 The Urban-Brookings Tax Policy Center 2005 Annual Report OVERVIEW The Urban Institute–Brookings -

America's Fiscal Choices at a Crossroad

MARCH 2011 AMERICA ’S FISCAL CHOICES AT A CROSSROAD The Human Side of the Fiscal Crisis ANNE VORCE COMMITTEE FOR A RESPONSIBLE FEDERAL BUDGET This project was supported by a generous grant from the John D. and Catherine T. MacArthur Foundation. HAIRMEN C Committee for a Responsible Federal Budget BILL FRENZEL JIM NUSSLE TIM PENNY The Committee for a Responsible Federal Budget is a CHARLIE STENHOLM bipartisan, non-profit organization committed to educating DIRECTORS the public about issues that have significant fiscal policy BARRY ANDERSON impact. The Committee’s board includes many of the past ROY ASH leaders of the Budget Committees, the Congressional Budget Office, the CHARLES BOWSHER STEVE COLL Office of Management and Budget, the Government Accountability Office, DAN CRIPPEN and the Federal Reserve Board. VIC FAZIO WILLIAM GRADISON WILLIAM GRAY , III The Fiscal Roadmap Project WILLIAM HOAGLAND DOUGLAS HOLTZ -EAKIN This paper is a product of the Fiscal Roadmap Project of the Committee for JIM JONES LOU KERR a Responsible Federal Budget, which was created to help policymakers JIM KOLBE navigate the country's serious economic and fiscal challenges. JAMES MCINTYRE , JR. DAVID MINGE MARNE OBERNAUER , JR. New America Foundation JUNE O’N EILL PAUL O’N EILL Since 2003, the Committee for a Responsible Federal Budget has been RUDOLPH PENNER PETER PETERSON housed at the New America Foundation. New America is an independent, ROBERT REISCHAUER non-partisan, non-profit public policy institute that brings exceptionally ALICE RIVLIN promising new voices and new ideas to the fore of our nation's public CHARLES ROBB MARTIN SABO discourse.