International Plant Genetic Resources Instit., (IPGRI)

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Quarantine Regulation for Importation of Plants

Quarantine Requirements for The Importation of Plants or Plant Products into The Republic of China Bureau of Animal and Plant Health Inspection and Quarantine Council of Agriculture Executive Yuan In case of any discrepancy between the Chinese text and the English translation thereof, the Chinese text shall govern. Updated November 26, 2009 更新日期:2009 年 12 月 16 日 - 1 - Quarantine Requirements for The Importation of Plants or Plant Products into The Republic of China A. Prohibited Plants or Plant Products Pursuant to Paragraph 1, Article 14, Plant Protection and Quarantine Act 1. List of prohibited plants or plant products, countries or districts of origin and the reasons for prohibition: Plants or Plant Products Countries or Districts of Origin Reasons for Prohibition 1. Entire or any part of the All countries and districts 1. Rice hoja blanca virus following living plants (Tenuivirus) (excluding seeds): 2. Rice dwarf virus (1) Brachiaria spp. (Phytoreovirus) (2) Echinochloa spp. 3. Rice stem nematode (3) Panicum spp. (Ditylenchus angustus (4) Paspalum spp. Butler) (5) Oryza spp., Leersia hexandra, Saccioleps interrupta (6) Rottboellia spp. (7) Triticum aestivum 2. Entire or any part of the Asia and Pacific Region West Indian sweet potato following living plants (1) Palau weevil (excluding seeds) (2) China (Euscepes postfasciatus (1) Calystegia spp. (3) Cook Islands Fairmaire) (2) Dioscorea japonica (4) Federated States of Micronesia (3) Ipomoea spp. (5) Fiji (4) Pharbitis spp. (6) Guam (7) Kiribati (8) New Caledonia (9) Norfolk Island -

Download The

9* PSEUDORECOMBINANTS OF CHERRY LEAF ROLL VIRUS by Stephen Michael Haber B.Sc. (Biochem.), University of British Columbia, 1975 A THESIS SUBMITTED IN PARTIAL FULFILLMENT OF THE REQUIREMENTS FOR THE DEGREE OF MASTER OF SCIENCE in THE FACULTY OF GRADUATE STUDIES (The Department of Plant Science) We accept this thesis as conforming to the required standard THE UNIVERSITY OF BRITISH COLUMBIA July, 1979 ©. Stephen Michael Haber, 1979 In presenting this thesis in partial fulfilment of the requirements for an advanced degree at the University of British Columbia, I agree that the Library shall make it freely available for reference and study. I further agree that permission for extensive copying of this thesis for scholarly purposes may be granted by the Head of my Department or by his representatives. It is understood that copying or publication of this thesis for financial gain shall not be allowed without my written permission. Department of Plant Science The University of British Columbia 2075 Wesbrook Place Vancouver, Canada V6T 1W5 Date Jul- 27. 1Q7Q ABSTRACT Cherry leaf roll virus, as a nepovirus with a bipartite genome, can be genetically analysed by comparing the properties of distinct 'parental' strains and the pseudorecombinant isolates generated from them. In the present work, the elderberry (E) and rhubarb (R) strains were each purified and separated into their middle (M) and bottom (B) components by sucrose gradient centrifugation followed by near- equilibrium banding in cesium chloride. RNA was extracted from the the separated components by treatment with a dissociation buffer followed by sucrose gradient centrifugation. Extracted M-RNA of E-strain and B-RNA of R-strain were mixed and inoculated to a series of test plants as were M-RNA of R-strain and B-RNA of E-strain. -

NBPGR Okf"Kzd Izfrosnu ANNUAL REPORT 2012-2013

ISSN NO 0971-2572 NBPGR okf"kZd izfrosnu ANNUAL REPORT 2012-2013 jk"Vªh; ikni vkuqOakf'kd Laklk/u C;wjks (Hkkjrh; Ñf"k vuqLak/ku ifj"kn) iwlk ifjlj] ubZ fnYyh&110 012 NATIONAL BUREAU OF PLANT GENETIC RESOURCES (Indian Council of Agricultural Research) Pusa Campus, New Delhi - 110 012 Citation : Anonymous (2013). Annual Report of the National Bureau of Plant Genetic Resources 2012-2013, NBPGR, Pusa Campus, New Delhi, India, 186+vi p. Compiled and Edited by : Dr. Arjun Lal, Principal Scientist Dr. (Mrs.) Kavita Gupta, Principal Scientist Dr. (Mrs.) Vandana Tyagi, Principal Scientist Dr. (Mrs.) Sangita Yadav, Senior Scientist This report includes unprocessed or semi-processed data, which would form the basis of scientific papers in due course. The material contained in the report therefore may not be made use of without the written permission of the Director, National Bureau of Plant Genetic Resources, New Delhi except for quoting it for scientific reference. Published by the Director, National Bureau of Plant Genetic Resources, Pusa Campus, New Delhi-110 012, and Printed at Alpha Printographics (India), New Delhi-110 028. Tel.: 9999039940, 9811199620 CONTENTS Preface Executive Summary 1 Introduction 9 NBPGR Headquarters, New Delhi 1. Plant Exploration and Germplasm Collection 13 2. Germplasm Evaluation 19 3. Germplasm Conservation 40 4. Plant Quarantine 45 5. Germplasm Exchange 53 6. Tissue Culture and Cryopreservation 60 7. PGR Policy Planning 65 8. Agricultural Knowledge Management 67 9. Genomic Resources 70 NBPGR Regional Stations/ Base Centers 10. Regional Station, Akola 86 11. Regional Station, Bhowali 91 12. Base Center, Cuttack 96 13. -

Genomic Characterization of the Cacao Swollen Shoot Virus Complex and Other Theobroma Cacao-Infecting Badnaviruses

Genomic Characterization of the Cacao Swollen Shoot Virus Complex and other Theobroma Cacao-Infecting Badnaviruses Item Type text; Electronic Dissertation Authors Chingandu, Nomatter Publisher The University of Arizona. Rights Copyright © is held by the author. Digital access to this material is made possible by the University Libraries, University of Arizona. Further transmission, reproduction or presentation (such as public display or performance) of protected items is prohibited except with permission of the author. Download date 29/09/2021 07:25:04 Link to Item http://hdl.handle.net/10150/621859 GENOMIC CHARACTERIZATION OF THE CACAO SWOLLEN SHOOT VIRUS COMPLEX AND OTHER THEOBROMA CACAO-INFECTING BADNAVIRUSES by Nomatter Chingandu __________________________ A Dissertation Submitted to the Faculty of the SCHOOL OF PLANT SCIENCES In Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements For the Degree of DOCTOR OF PHILOSOPHY WITH A MAJOR IN PLANT PATHOLOGY In the Graduate College THE UNIVERSITY OF ARIZONA 2016 1 THE UNIVERSITY OF ARIZONA GRADUATE COLLEGE As members of the Dissertation Committee, we certify that we have read the dissertation prepared by Nomatter Chingandu, entitled “Genomic characterization of the Cacao swollen shoot virus complex and other Theobroma cacao-infecting badnaviruses” and recommend that it be accepted as fulfilling the dissertation requirement for the Degree of Doctor of Philosophy. _______________________________________________________ Date: 7.27.2016 Dr. Judith K. Brown _______________________________________________________ Date: 7.27.2016 Dr. Zhongguo Xiong _______________________________________________________ Date: 7.27.2016 Dr. Peter J. Cotty _______________________________________________________ Date: 7.27.2016 Dr. Barry M. Pryor _______________________________________________________ Date: 7.27.2016 Dr. Marc J. Orbach Final approval and acceptance of this dissertation is contingent upon the candidate’s submission of the final copies of the dissertation to the Graduate College. -

DISEASE RESISTANCE TESTING in COCOA a Review on Behalf of FAO/INGENIC J.C. Zadoks, Consultant

Zadoks - Disease resistance in cocoa 1997 February 2, 1997 DISEASE RESISTANCE TESTING IN COCOA A review on behalf of FAO/INGENIC J.C. Zadoks, consultant do Department of Phytopathology P.O.Box 8025 6700 EE Wageningen The Netherlands private fax + 31 - 317 - 48 34 12 fax + 31 - 317 - 42 36 14 e-mail Jan Carel [email protected] [email protected] - (hoi o Zadoks - Disease resistance in cocoa 1997 TABLE OF CONTENTS 0. Executive summary 1. Introduction 1.1. INGENIC 1.2. Objectives of the review 1.3. Procedure 2. Background information. The host plant 2.1. Origin 2.2. Agronomy 2.3. Genetics 2.4. Breeding 2.5. Pre-breeding 2.6. Conclusions and recommendations 3. Background information. The pathogens 3.1. Taxonom ic cons iderations 3.2. Subspecific variation 3.3. Selected pathogens 3.4. General comments 4. Resistance testing 4.1. Resistance, tolerance and escape 4.2. Components of resistance 4.3. Host-parasite interactions 4.4. Methods of resistance testing 4.5. Predictive tests 4.6. Resistance tests in campo 4.7. Resistance tests in vivo 4.8. Biochemical and molecular tests 4.9. International aspects of resistance testing 5. Resistance 5.1. Past and present situation of resistance breeding 5.2. Breeding objectives 5.3. Results with selected pathogens 5.4. Molecular techniques 5.5. General comments 5.6. Conclusions 2 Zadoks - Disease resistance in cocoa 1997 6. International cooperation 6.1. Organizational aspects 6.2. Needs 6.3. Pre-breeding 6.4. Preliminaries to implementation 6.5. Quality standards 6.6. Recommendations 7. -

Ajay Kumar Tiwari Editor Advances in Seed Production and Management Advances in Seed Production and Management Ajay Kumar Tiwari Editor

Ajay Kumar Tiwari Editor Advances in Seed Production and Management Advances in Seed Production and Management Ajay Kumar Tiwari Editor Advances in Seed Production and Management Editor Ajay Kumar Tiwari UP Council of Sugarcane Research Shahjahanpur, Uttar Pradesh, India ISBN 978-981-15-4197-1 ISBN 978-981-15-4198-8 (eBook) https://doi.org/10.1007/978-981-15-4198-8 # Springer Nature Singapore Pte Ltd. 2020 This work is subject to copyright. All rights are reserved by the Publisher, whether the whole or part of the material is concerned, specifically the rights of translation, reprinting, reuse of illustrations, recitation, broadcasting, reproduction on microfilms or in any other physical way, and transmission or information storage and retrieval, electronic adaptation, computer software, or by similar or dissimilar methodology now known or hereafter developed. The use of general descriptive names, registered names, trademarks, service marks, etc. in this publication does not imply, even in the absence of a specific statement, that such names are exempt from the relevant protective laws and regulations and therefore free for general use. The publisher, the authors, and the editors are safe to assume that the advice and information in this book are believed to be true and accurate at the date of publication. Neither the publisher nor the authors or the editors give a warranty, expressed or implied, with respect to the material contained herein or for any errors or omissions that may have been made. The publisher remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. This Springer imprint is published by the registered company Springer Nature Singapore Pte Ltd. -

List of Viruses Presenting at the Wild State a Biological Risk for Plants

December 2008 List of viruses presenting at the wild state a biological risk for plants CR Species 2 Abutilon mosaic virus 2 Abutilon yellows virus 2 Aconitum latent virus 2 African cassava mosaic virus 2 Ageratum yellow vein virus 2 Agropyron mosaic virus 2 Ahlum waterborne virus 2 Alfalfa cryptic virus 1 2 Alfalfa mosaic virus 2 Alsike clover vein mosaic virus 2 Alstroemeria mosaic virus 2 Amaranthus leaf mottle virus 2 American hop latent virus ( ← Hop American latent virus) 2 American plum line pattern virus 2 Anthoxanthum latent blanching virus 2 Anthriscus yellows virus 2 Apple chlorotic leaf spot virus 2 Apple mosaic virus 2 Apple stem grooving virus 2 Apple stem pitting virus 2 Arabis mosaic virus satellite RNA 2 Araujia mosaic virus 2 Arracacha virus A 2 Artichoke Italian latent virus 2 Artichoke latent virus 2 Artichoke mottled crinkle virus 2 Artichoke yellow ringspot virus 2 Asparagus virus 1 2 Asparagus virus 2 2 Avocado sunblotch viroid 2 Bajra streak virus 2 Bamboo mosaic virus 2 Banana bract mosaic virus 2 Banana bunchy top virus 2 Banana streak virus 2 Barley mild mosaic virus page 1 December 2008 2 Barley mosaic virus 3 Barley stripe mosaic virus 2 Barley yellow dwarf virus-GPV 2 Barley yellow dwarf virus-MAV 2 Barley yellow dwarf virus-PAV 2 Barley yellow dwarf virus-RGV 2 Barley yellow dwarf virus-RMV 2 Barley yellow dwarf virus-SGV 2 Barley yellow mosaic virus 2 Barley yellow streak mosaic virus 2 Barley yellow striate mosaic virus 2 Bean calico mosaic virus 2 Bean common mosaic necrosis virus 2 Bean common mosaic -

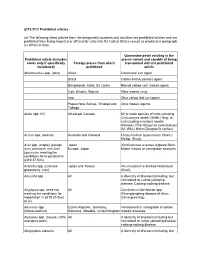

319.37-2 Prohibited Articles

§319.37-2 Prohibited articles. (a) The following listed articles from the designated countries and localities are prohibited articles and are prohibited from being imported or offered for entry into the United States except as provided in paragraph (c) of this section. Quarantine pests existing in the Prohibited article (includes places named and capable of being seeds only if specifically Foreign places from which transported with the prohibited mentioned) prohibited article Abelmoschus spp. (okra) Africa Cotton leaf curl agent. Brazil Cotton Anthocyanosis agent. Bangladesh, India, Sri Lanka Bhendi yellow vein mosaic agent. Cote d'Ivoire, Nigeria Okra mosaic virus. Iraq Okra yellow leaf curl agent. Papua New Guinea, Trinidad and Okra mosaic agents. Tobago Abies spp. (fir) All except Canada 50 or more species of rusts including Chrysomyxa abietis (Wallr.) Ung. (a rust causing a serious needle disease); Phacidiopycnis pseudotsuga (M. Wils.) Hahn (Douglas fir canker). Acacia spp. (acacia) Australia and Oceania Uromycladium tepperianum (Sacc.) McAlp. (Rust). Acer spp. (maple) (except Japan Xanthomonas acernea (Ogawa) Burk. Acer palmatum and Acer Europe, Japan Maple mosaic or variegation diseases. japonicum meeting the conditions for importation in §319.37-5(m) Actinidia spp. (Chinese Japan and Taiwan Pucciniastrum actinidiae Hiratusuka gooseberry, kiwi). (Rust). Adonidia spp All A diversity of diseases including, but not limited to: Lethal yellowing disease; Cadang-cadang disease. Aeglopsis spp. seed not All Candidatus Liberibacter spp. meeting the conditions for (Huanglongbing disease of citrus, importation in §319.37-5(w) Citrus greening). or (x). Aesculus spp. Czech Republic, Germany, Horsechestnut variegation or yellow (horsechestnut) Romania, Slovakia, United Kingdom mosaic diseases. -

9780851990163.Pdf

This page intentionally left blank S.E. Albrechtsen Danish Seed Health Centre for Developing Countries Thorvaldsensvej 40, DK-1871 Frederiksberg C, Denmark formerly Danish Government Institute of Seed Pathology for Developing Countries CABI Publishing CABI Publishing is a division of CAB International CABI Publishing CABI Publishing CAB International 875 Massachusetts Avenue Wallingford 7th Floor Oxfordshire OX10 8DE Cambridge, MA 02139 UK USA Tel: +44 (0)1491 832111 Tel: +1 617 395 4056 Fax: +44 (0)1491 833508 Fax: +1 617 354 6875 E-mail: [email protected] E-mail: [email protected] Website: www.cabi-publishing.org S.E. Albrechtsen 2006. All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced in any form or by any means, electronically, mechanically, by photocopying, recording or otherwise, without the prior permission of the copyright owners. A catalogue record for this book is available from the British Library, London, UK. ISBN 0 85199 016 9 Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data Albrechtsen, S.E. (Sven Erik) Testing methods for seed-transmitted viruses: principles and protocols / S.E. Albrechtsen. p. cm. Includes bibliographical references and index. ISBN 0-85199-016-9 (alk. paper) 1. Seeds--Testing. 2. Seed pathology. 3. Virus diseases of plants. I. Title. SB117.A35 2005 632′.8--dc22 2005003343 Typeset by AMA DataSet Ltd, UK. Printed and bound in the UK by Biddles Ltd, King’s Lynn. Contents Preface ix Acknowledgements xi PART I 1 Introduction 1 1.1. Seed-transmitted Viruses and Viroids 1 1.2. The Development of the Science 2 1.2.1. Seed-health testing for viruses 3 1.3. -

Virus Integration and Tandem Repeats in the Genomes of Petunia a Thesis

Virus integration and tandem repeats in the genomes of Petunia A thesis submitted to the University of Leicester for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy By Osamah Nadhim Kadhim Alisawi M.Sc. January 2019 Department of Genetics and Genome Biology i Abstract The integration of endogenous pararetroviruses (EPRVs) and tandemly repeated sequences were examined in whole genome raw reads, and two genome assemblies, in diploid Petunia species including hybrid-derivatives and their ancestors, using bioinformatics, molecular biology, cytogenetics and microscopy. Three types of EPRV clusters (petuvirus-, florendovirus- and caulimovirus-like sequences) were found. Chromosomal signals of PVCV (Petunia vein clearing virus) were seen by in situ hybridization in all Petunia species. Fragmented parts of four novel florendovirus-like sequences were found and the complete sequence was reconstructed, adding petunia to the 27 known host species. Chromosome III of P. axillaris and P. hybrida Rdc showed strong pericentromeric signal of PVCV and Florendovirus suggesting both EPRVs have similar positions, integration patterns and endogenization events (unlike P. integrifolia subsp inflata and P. axillaris subsp parodii). The caulimovirus-like sequence cluster was less abundant in genomes, with four novel members. RNA analysis from infected and healthy petunia samples revealed expression of endogenous PVCV and Caulimovirus sequences, unlike Florendovirus (not detected in RNA). The episomal form of vertically transmitted PVCV was integrated near the telomere of heterologous chromosomes. Transmission electron microscopy (TEM) showed differences in number and size of PVCV particles and inclusion bodies for both chlorotic spots and vein clearing symptoms, the latter correlated with PVCV particles in cytoplasm from vascular bundle cells. -

Open Melnick Phd Thesis.Pdf

The Pennsylvania State University The Graduate School Department of Plant Pathology ENDOPHYTIC BACILLUS SPP. OF THEOBROMA CACAO: ECOLOGY AND POTENTIAL FOR BIOLOGICAL CONTROL OF CACAO DISEASES A Dissertation in Plant Pathology by Rachel L. Melnick 2010 Rachel L. Melnick Submitted in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree of Doctor of Philosophy May 2010 The dissertation of Rachel L. Melnick was reviewed and approved* by the following: Paul A. Backman Professor of Plant Pathology Dissertation Advisor Chair of Committee Bryan A. Bailey Adjunct Professor of Plant Pathology Plant Pathologist at USDA-ARS SPCL Special Member Maria del Mar Jimenez-Gasco Assistant Professor of Plant Pathology Gary W. Moorman Professor of Plant Pathology Roger T. Koide Professor of Horticultural Ecology Frederick E. Gildow Professor of Plant Pathology Head of the Department of Plant Pathology *Signatures are on file in the Graduate School iii ABSTRACT Yield of Theobroma cacao, the chocolate tree, is drastically limited by disease. In South America, there are three key diseases: black pod, caused by Phytophthora spp.; frosty pod, caused by Moniliophthora roreri; and witches‟ broom, caused by Moniliophthora perniciosa. Although chemical control options exist, farmers typically only use cultural disease management such as phytosanitary pruning. Agrochemical use can be problematic in the developing countries where cacao is grown due to large risks to human health and the environment. There has been increased interest in the use of biological control for management of cacao diseases due to problems associated with pesticide use as well as consumer desire for organic chocolate. Fungal species have been the main focus for research on biological control of cacao diseases, while cacao- associated bacteria have been nearly ignored. -

Iillf .Me Clue to a Speci8llmllllitmty Ofcertain Orglals, Tissues Or Organeues to Die Cocoa Virus

UNIVEIlSITY OF CAPE COAST IIIOCHIiMlCAL STUDIES OF RESISTANCE LEVELS OF COCOA VABJBTIES AT COCOA RESEARCH INSTITUTE OF GHANA, TAFO-AKIM TO COCOA SWOLLEN SHOOT VIRUS. CLMS ...0. BY .A(:CESSION NO. 28711 I DANIEL KOJO MANU CIIf''t .QlEro(f FINAL CHeeK \ ~ . I ~.,.... ._._~--- 11IESIS SUBMITTED TO THE DEPARTMENT OF CROP SCIENCE OF THE SCHOOL OF AGRICULTURE, UNIVERSITY OF CAPE COAST IN PARTIAL FULFILMENT OF THE REQUIREMENTS FOR THE AWARD OF MASTER OF PHILOSOPHY DEGREE IN CROP SCIENCE. MARCH, 2006. _ ll ."-iiE. fillIn ClAn .. DECLARATION CANDIDATE'S DECLARATION I bereby declare that this thesis is the result ofmy own original researc~ and that DO part ofit has been presented for another degree in this university orl elsewhere. r Candidate's Signature..~ Date .. ?-::f7.1. ?~ ~~l Name: Daniel Kojo Manu - SUPERVISORS' DECLARATION We hereby declare that the preparation and presentation of the thesis were supervised in accordance with the guidelines on supervision of thesis laid dowil by the University ofCape Coast. ~y(~ Prin,'poI Sup="",', S''''''ore.. .f1f.'.. .'" O'k.... Name: Mr. Yaw Opoku-Asiama C~S"P='~'" S,,,,,m,, .. ~,,)c:h.1J:67'. Name: Mr. Patrick Constantine Aculey ii ~·'i • ,. ABSTRACf BiodIemic:alllvdies were carried out on ten cocoa types to find out their 4iffeJelit levels of resistance to Cocoa Swollen Shoot Virus. The beans were iDoc:ula&ed via viruliferous nymphs ofmealy bugs, and observed after planting for 3 months. Patches of barks of severe symptom bearing cocoa types were also tested through grafting on healthy Amelonado plants and observed for 3 months. Significant differences were observed in the cocoa types in terms of symptoms appearance and in severity.