DOCUMENT RESUME ED 404 077 RC 020 917 Koesler, Rena

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

States of Incarceration and Subordination in the Learning and Lived Experiences of Youth in a Juvenile Detention Facility

ARE THE[SE] KIDS ALRIGHT?: STATES OF INCARCERATION AND SUBORDINATION IN THE LEARNING AND LIVED EXPERIENCES OF YOUTH IN A JUVENILE DETENTION FACILITY by Jonathan Patrick Arendt A thesis submitted in conformity with the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy Graduate Department of Curriculum, Teaching, and Learning Ontario Institute for Studies in Education University of Toronto © Copyright by Jonathan Patrick Arendt 2012 ARE THE[SE] KIDS ALRIGHT?: STATES OF INCARCERATION AND SUBORDINATION IN THE LEARNING AND LIVED EXPERIENCES OF YOUTH IN A JUVENILE DETENTION FACILITY Doctor of Philosophy 2012 Jonathan Patrick Arendt Department of Curriculum, Teaching, and Learning University of Toronto ABSTRACT This study examines the dynamics and implications of trans-spatial subordination in/across the lived experiences of six incarcerated participant youths in a secure custody facility for juveniles in Louisiana. Five male teenagers (four African American, one White) and one female teenager (African American) discuss the limitations, harassment, and confinement in various aspects of their lives and speak about the impact on their expectations for the future. The author employs several methodologies in order to develop a multimedia, multifaceted representation of their lives. The narratives elicited through interviews provide the bulk of the data as the participants describe this perpetual subordination. The photographs, resulting from the implementation of a visual ethnographic methodology, provide images that serve as catalysts for introspection and analysis of significance in the mundane and routine, particularly as they apply to the carceral facilities, structures, and policies themselves. Film viewing and discussion offer an array of depictions of youth and criminality to which the youths responded, granting a simultaneous peek at how these marginalized youths viewed themselves and how mainstream media productions depict them. -

AMNH Digital Library

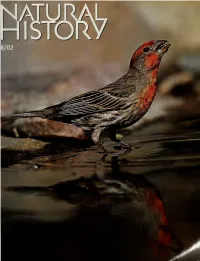

^^<e?& THERE ARE THOSE WHO DO. AND THOSE WHO WOULDACOULDASHOULDA. Which one are you? If you're the kind of person who's willing to put it all on the line to pursue your goal, there's AIG. The organization with more ways to manage risk and more financial solutions than anyone else. Everything from business insurance for growing companies to travel-accident coverage to retirement savings plans. All to help you act boldly in business and in life. So the next time you're facing an uphill challenge, contact AIG. THE GREATEST RISK IS NOT TAKING ONE: AIG INSURANCE, FINANCIAL SERVICES AND THE FREEDOM TO DARE. Insurance and services provided by members of American International Group, Inc.. 70 Pine Street, Dept. A, New York, NY 10270. vww.aig.com TODAY TOMORROW TOYOTA Each year Toyota builds more than one million vehicles in North America. This means that we use a lot of resources — steel, aluminum, and plastics, for instance. But at Toyota, large scale manufacturing doesn't mean large scale waste. In 1992 we introduced our Global Earth Charter to promote environmental responsibility throughout our operations. And in North America it is already reaping significant benefits. We recycle 376 million pounds of steel annually, and aggressive recycling programs keep 18 million pounds of other scrap materials from landfills. Of course, no one ever said that looking after the Earth's resources is easy. But as we continue to strive for greener ways to do business, there's one thing we're definitely not wasting. And that's time. www.toyota.com/tomorrow ©2001 JUNE 2002 VOLUME 111 NUMBER 5 FEATURES AVIAN QUICK-CHANGE ARTISTS How do house finches thrive in so many environments? By reshaping themselves. -

'The Wesleyan Way'

$2 Annual Conference-July 2011 Season of Pentecost Gadson on ‘audacity of faith’ Page 10 “Are you ready, South Carolina, for what God will do with us together?” Bishop Mary Virginia Taylor asked in the opening service of Annual Conference. (Photos by Jessica Connor) ‘The Wesleyan Way’ a time of worship, of praise, of fellowship the balance between theme and the busi - 31 commissioned United Methodists elect and of legislation. ness of the conference – and not keep peo - or ordained delegates, set budget, Members left Sunday afternoon after ple stuck in business hours after the event Page 2 what Taylor referred to in her closing ser - was slated to close. Key was the shifting pass legislation at 2011 mon as the “great breeze” of the Holy of the final day of business to Saturday Spirit swept through the arena and led the instead of Sunday, and moving the ordina - Annual Conference body to elect delegates to Jurisdictional tion service to the last day of conference and General Conferences in 2012, deter - (Sunday). FLORENCE – “Can you feel it? Can you mine the 2012 conference budget and vote In addition to election for delegates, sense it?” Bishop Mary Virginia Taylor on a host of resolutions. significant this year were a vote on a new, asked members of Annual Conference. Taylor reported at the event’s close that streamlined structure for the Connectional “Are you ready, South Carolina, for what 1,640 members – 846 laity, 795 clergy – Ministries arm of the conference, a shift to God will do with us together?” were in attendance. -

The Oxford Democrat

The Oxford Democrat. NUMBER 49. VOLUME 73. SOUTH PARIS, MAINE, TUESDAY, DECEMBER 4, 1906. '•Say. that's many!" ho cried. "I'c —α shiver that bad la it something Tremalne and I, and I felt myself lbkrt d. park, Have a Feast of Raaaon. May purty nigh fergot It Early this fearfully delightful. And let me add yielding to tlic fascination of the song, γ AMONG THE FAMEES. The foreword In relation to following raorniu' tbey was somebody—a wo here that the emotion which Cecily— even as tbe serpent did. It wtis not Licensed Auctioneer, coarse the Uni- the lecture prepared bj ine and so I came to know her—raised In formi- τω plow." The mm" He came close to for very large, nor seemingly very SOUTH PARIS, MAIMS. "•run versity of Maine along agricultural lines bis voice to a hoarse wbleper. me was not in the least admiration In so I did not even think of fear Housekeepers Term· Moderate. for the present winter shonld be read by dropped dable, r'D' know who I think It was? That the ordinary sense of the term, but when the little door of Correspondence on practical agricultural topics every member of the Grange and other y' Cecily opened In- fascination, when P. BARNES, la solicite· 1. Address all communication· farmers' after which in- Croydon woman!" rather an overpowering tbe cage and drew It forth. She held It have been vexed tended for this to Hkxbt D. organizations, department some amazement such as oue sometimes feels In watch- ^jUARLES Hammond, Editor Oxford Dem fluence should be exerted to secure I stared at blm In between thumb and finger just behind Agricultural back cream of tartar Attorney at Law, ocrai, Paris, lie. -

Idioms-And-Expressions.Pdf

Idioms and Expressions by David Holmes A method for learning and remembering idioms and expressions I wrote this model as a teaching device during the time I was working in Bangkok, Thai- land, as a legal editor and language consultant, with one of the Big Four Legal and Tax companies, KPMG (during my afternoon job) after teaching at the university. When I had no legal documents to edit and no individual advising to do (which was quite frequently) I would sit at my desk, (like some old character out of a Charles Dickens’ novel) and prepare language materials to be used for helping professionals who had learned English as a second language—for even up to fifteen years in school—but who were still unable to follow a movie in English, understand the World News on TV, or converse in a colloquial style, because they’d never had a chance to hear and learn com- mon, everyday expressions such as, “It’s a done deal!” or “Drop whatever you’re doing.” Because misunderstandings of such idioms and expressions frequently caused miscom- munication between our management teams and foreign clients, I was asked to try to as- sist. I am happy to be able to share the materials that follow, such as they are, in the hope that they may be of some use and benefit to others. The simple teaching device I used was three-fold: 1. Make a note of an idiom/expression 2. Define and explain it in understandable words (including synonyms.) 3. Give at least three sample sentences to illustrate how the expression is used in context. -

ED311449.Pdf

DOCUMENT RESUME ED 311 449 CS 212 093 AUTHOR Baron, Dennis TITLE Declining Grammar--and Other Essays on the English Vocabulary. INSTITUTION National Council of Teachers of English, Urbana, Ill. REPORT NO ISBN-0-8141-1073-8 PUB DATE 89 NOTE :)31p. AVAILABLE FROM National Council of Teachers of English, 1111 Kenyon Rd., Urbana, IL 61801 (Stock No. 10738-3020; $9.95 member, $12.95 nonmember). PUB TYPE Books (010) -- Viewpoints (120) EDRS PRICE MF01/PC10 Plus Postage. DESCRIPTORS *English; Gr&mmar; Higher Education; *Language Attitudes; *Language Usage; *Lexicology; Linguistics; *Semantics; *Vocabulary IDENTIFIERS Words ABSTRACT This book contains 25 essays about English words, and how they are defined, valued, and discussed. The book is divided into four sections. The first section, "Language Lore," examines some of the myths and misconceptions that affect attitudes toward language--and towards English in particular. The second section, "Language Usage," examines some specific questions of meaning and usage. Section 3, "Language Trends," examines some controversial r trends in English vocabulary, and some developments too new to have received comment before. The fourth section, "Language Politics," treats several aspects of linguistic politics, from special attempts to deal with the ethnic, religious, or sex-specific elements of vocabulary to the broader issues of language both as a reflection of the public consciousness and the U.S. Constitution and as a refuge for the most private forms of expression. (MS) *********************************************************************** Reproductions supplied by EDRS are the best that can be made from the original document. *********************************************************************** "PERMISSION TO REPRODUCE THIS MATERIAL HAS BEEN GRANTED BY J. Maxwell TO THE EDUCATIONAL RESOURCES INFORMATION CENTER (ERIC)." U S. -

Haitian Creole – English Dictionary

+ + Haitian Creole – English Dictionary with Basic English – Haitian Creole Appendix Jean Targète and Raphael G. Urciolo + + + + Haitian Creole – English Dictionary with Basic English – Haitian Creole Appendix Jean Targète and Raphael G. Urciolo dp Dunwoody Press Kensington, Maryland, U.S.A. + + + + Haitian Creole – English Dictionary Copyright ©1993 by Jean Targète and Raphael G. Urciolo All rights reserved. No part of this work may be reproduced or transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic or mechanical, including photocopying and recording, or by any information storage and retrieval system, without the prior written permission of the Authors. All inquiries should be directed to: Dunwoody Press, P.O. Box 400, Kensington, MD, 20895 U.S.A. ISBN: 0-931745-75-6 Library of Congress Catalog Number: 93-71725 Compiled, edited, printed and bound in the United States of America Second Printing + + Introduction A variety of glossaries of Haitian Creole have been published either as appendices to descriptions of Haitian Creole or as booklets. As far as full- fledged Haitian Creole-English dictionaries are concerned, only one has been published and it is now more than ten years old. It is the compilers’ hope that this new dictionary will go a long way toward filling the vacuum existing in modern Creole lexicography. Innovations The following new features have been incorporated in this Haitian Creole- English dictionary. 1. The definite article that usually accompanies a noun is indicated. We urge the user to take note of the definite article singular ( a, la, an or lan ) which is shown for each noun. Lan has one variant: nan. -

THE COLLECTED POEMS of HENRIK IBSEN Translated by John Northam

1 THE COLLECTED POEMS OF HENRIK IBSEN Translated by John Northam 2 PREFACE With the exception of a relatively small number of pieces, Ibsen’s copious output as a poet has been little regarded, even in Norway. The English-reading public has been denied access to the whole corpus. That is regrettable, because in it can be traced interesting developments, in style, material and ideas related to the later prose works, and there are several poems, witty, moving, thought provoking, that are attractive in their own right. The earliest poems, written in Grimstad, where Ibsen worked as an assistant to the local apothecary, are what one would expect of a novice. Resignation, Doubt and Hope, Moonlight Voyage on the Sea are, as their titles suggest, exercises in the conventional, introverted melancholy of the unrecognised young poet. Moonlight Mood, To the Star express a yearning for the typically ethereal, unattainable beloved. In The Giant Oak and To Hungary Ibsen exhorts Norway and Hungary to resist the actual and immediate threat of Prussian aggression, but does so in the entirely conventional imagery of the heroic Viking past. From early on, however, signs begin to appear of a more personal and immediate engagement with real life. There is, for instance, a telling juxtaposition of two poems, each of them inspired by a female visitation. It is Over is undeviatingly an exercise in romantic glamour: the poet, wandering by moonlight mid the ruins of a great palace, is visited by the wraith of the noble lady once its occupant; whereupon the ruins are restored to their old splendour. -

Marlboro College, a Memoir Tom Ragle, President Emeritus

Marlboro College, A Memoir Tom Ragle, President Emeritus Document PDF TABLE OF CONTENTS Page Page FOREWARD TO THE PROPOSED 2020 REPRINTS i 2 / 257 PROLOGUE 1 8 / 257 CHAPTER ONE – WALTER HENDRICKS AND THE EARLY YEARS 3 10 / 257 CHAPTER TWO – SETTING THE COURSE: 1958-1960 7 14 / 257 CHAPTER THREE – THE PACE QUICKENS: 1960-65 25 32 / 257 CHAPTER FOUR – THE CHANGING OF THE GUARD: 1965-1969 75 82 / 257 CHAPTER FIVE – "THE GLORIOUS REVOLUTION" OF 1969 101 108 / 257 CHAPTER SIX – INTERLUDE: 1969-1970 112 119 / 257 CHAPTER SEVEN – HIGH WATER MARK, 1969-1973 114 121 / 257 CHAPTER EIGHT – EBB TIDE, 1973-1977 142 149 / 257 CHAPTER NINE – STORMY WEATHER: 1977-1981 182 189 / 257 APPENDIX A 223 230 / 257 APPENDIX B 228 235 / 257 APPENDIX C 234 241 / 257 APPENDIX D 239 246 / 257 © 2020 by Tom Ragle. All rights reserved. FOREWARD TO THE PROPOSED 2020 REPRINTS* In the fall of 2019 I was invited by the College to write a forward for the second printing of Marlboro College, A Memoir, originally published in a very limited edition in 1999. This came as a surprise because the original document had been written simply as a typescript for the archives lest some fascinating bits about early years of the College be lost. Although it appeared in a strictly limited edition of sixty copies or so, it was never designed to be printed in the first place. This invitation came at an opportune time, however, for even as I wrote there were negotiations underway to merge Marlboro with Emerson College in Boston, Massachusetts, and move its operations to the city. -

K- 12 Approved Literature List by Title Title Author Gr

K- 12 Approved Literature List by Title Title Author Gr 1984 Orw ell, G 9 10 for Dinner Bo gart , J. 3 100 Book Race: Hog Wild in the Reading Room , The Giff, Patricia Reilly 1 1000 Acres, A Knoph, Alfred A. 12 101 Success Secrets for Gifted Kids, The Ultim ate Fonseca, Christina 6 Han d b o o k 11 Birthdays Mass, Wendy 4 12 Ways to Get to 11 Merriam , Eve 2 2001: A Space Odyssey Clarke, A. 6 2002: A Space Odyssey Clarke, A. 6 2061: Odyssey Three Clarke, A. 6 26 Fairmount Avenue dePaola, Tom ie 2 4 Valentines In A Rainstorm Bo n d , F. 1 5th of March Rinaldi, Ann 5 6 Titles: Eagles, Bees and Wasps, Alligators and Crocodiles, Morgan, Sally 1 Giraffes, Sharks, Tortoises and Turtles 79-Squares Bo sse 6 A Bad Case of Stripes Shannon, David K A Boy in the Doghouse, 1991 Duffey, Betsy 2 A Jar of Dream s Uch id a, Yo sh iko 4 A Jigsaw Jones Mystery Series Preller, Jam es 2 A Letter to Mrs. Roosevelt, 1999 C. Coco DeYoung 3 A Long Walk to Water Park, Linda Sue 6 updated April 10, 2015 *previously approved at higher grade level 1 K- 12 Approved Literature List by Title Title Author Gr A Long Way from Chicago Peck, Richard 2 A Long Way Gone Beah , Ish m ael 9 A Pocket Full of Kisses Penn, Audrey K A Year Down Yonder Peck, Richard 2 Abandoned Puppy Costello, Em ily 3 Abby My Love Irw in 6 ABC Bunny, The Gag, W. -

The Dial 1931

^:$m'mMmU^M'r- :.-: lufmm $pflf^^^^^ uMiumwu mm^ J ' ;:•:;;,•;,.- i ARCHIVES FramJngham StalQ CoHeg© FiamJngham, fi/«a£3achusett8 Wliittcmore Memorial Gate Dial State Normal School Trainindham^ Mass. 1931 PROLOGUE The way is full of care and strife Along this weary way of life Sometimes troubles overwhelm And we can barely keep the helm And oft times everything goes wrong, And hard it is to sing a song; Then the path just grows so steep, We lay aside our work and weep. 'Oh, should this old world treat us so When so far we yet must go?" We seem to hear a voice say, "No, The dark clouds soon away will go, And bright blue skies will then break through And life with joy will start anew." E. R. Vin 'If Dedicated TO 1 Miss Ramsdell I whose interest, willingness, and teachings have made our lives richer. Jul \Ju I MISS LOUIE G. RAMSDELL ; ! : ; To the Class of 1931 I have chosen to give you my message in the "Song of the Brown Thrush." May its inspiration help 3'ou to success and happiness through the days of your years. "This is the song the Brown Thrush flings Out of his thicket of roses Hark how it warbles and rings, Mark how it closes "Luck, luck, What luck ? Good enough for me! I'm alive, you see. Sun shining, No repining; Never borrow Idle sorrow; Drop it! Cover it up! Hold 3'our cup Joy will fill it, Don't spill it Steady, be ready. Good luck! " cuu/^^^lcui^ ; THOUGHT Thought is deeper than all speech Feeling deeper than all thought; Souls to souls can never teach What unto themselves was taught. -

Senate Asks Beer, Wine Service Rule

The Courier Volume 9 Issue 3 Article 1 10-9-1975 The Courier, Volume 9, Issue 3, October 9, 1975 The Courier, College of DuPage Follow this and additional works at: https://dc.cod.edu/courier This Issue is brought to you for free and open access by the College Publications at DigitalCommons@COD. It has been accepted for inclusion in The Courier by an authorized editor of DigitalCommons@COD. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Senate asks We try to tell it all, beer, wine says USIA analyst service rule By Gail Werth requires much time and effort to erase By Deborah Beaird Patty Hearst, Watergate and the oil that image, he said. The Alcoholic Beverage Policy was shortage are part of America’s Image Although its largest audience is among items discussed by Senate at their and are presented in all U.S. Information dedicated to radio. Voice of America, Oct. 2 meeting. This poUcy would allow Agencies abroad, Joel Rochow, analyst U.S.I.A. publishes more than 25 service of beer and wine at COD spon¬ for the U.S.I.A., told an Extension magazines, builds American Service sored functions such as banquets. College audience Tuesday night in Libraries, and exhibits depicting the Alcoholic beverages would not be per¬ Hinsdale. American way of life. mitted at concerts, films, speeches, “Every aspect on America is reported America isn’t the only country which picnics on campus, or athletic events. to other countries, whether good or bad, maintains an information agency. Russia Although such restrictions exist.