The George Wright Forum

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

States of Incarceration and Subordination in the Learning and Lived Experiences of Youth in a Juvenile Detention Facility

ARE THE[SE] KIDS ALRIGHT?: STATES OF INCARCERATION AND SUBORDINATION IN THE LEARNING AND LIVED EXPERIENCES OF YOUTH IN A JUVENILE DETENTION FACILITY by Jonathan Patrick Arendt A thesis submitted in conformity with the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy Graduate Department of Curriculum, Teaching, and Learning Ontario Institute for Studies in Education University of Toronto © Copyright by Jonathan Patrick Arendt 2012 ARE THE[SE] KIDS ALRIGHT?: STATES OF INCARCERATION AND SUBORDINATION IN THE LEARNING AND LIVED EXPERIENCES OF YOUTH IN A JUVENILE DETENTION FACILITY Doctor of Philosophy 2012 Jonathan Patrick Arendt Department of Curriculum, Teaching, and Learning University of Toronto ABSTRACT This study examines the dynamics and implications of trans-spatial subordination in/across the lived experiences of six incarcerated participant youths in a secure custody facility for juveniles in Louisiana. Five male teenagers (four African American, one White) and one female teenager (African American) discuss the limitations, harassment, and confinement in various aspects of their lives and speak about the impact on their expectations for the future. The author employs several methodologies in order to develop a multimedia, multifaceted representation of their lives. The narratives elicited through interviews provide the bulk of the data as the participants describe this perpetual subordination. The photographs, resulting from the implementation of a visual ethnographic methodology, provide images that serve as catalysts for introspection and analysis of significance in the mundane and routine, particularly as they apply to the carceral facilities, structures, and policies themselves. Film viewing and discussion offer an array of depictions of youth and criminality to which the youths responded, granting a simultaneous peek at how these marginalized youths viewed themselves and how mainstream media productions depict them. -

AMNH Digital Library

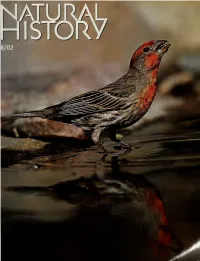

^^<e?& THERE ARE THOSE WHO DO. AND THOSE WHO WOULDACOULDASHOULDA. Which one are you? If you're the kind of person who's willing to put it all on the line to pursue your goal, there's AIG. The organization with more ways to manage risk and more financial solutions than anyone else. Everything from business insurance for growing companies to travel-accident coverage to retirement savings plans. All to help you act boldly in business and in life. So the next time you're facing an uphill challenge, contact AIG. THE GREATEST RISK IS NOT TAKING ONE: AIG INSURANCE, FINANCIAL SERVICES AND THE FREEDOM TO DARE. Insurance and services provided by members of American International Group, Inc.. 70 Pine Street, Dept. A, New York, NY 10270. vww.aig.com TODAY TOMORROW TOYOTA Each year Toyota builds more than one million vehicles in North America. This means that we use a lot of resources — steel, aluminum, and plastics, for instance. But at Toyota, large scale manufacturing doesn't mean large scale waste. In 1992 we introduced our Global Earth Charter to promote environmental responsibility throughout our operations. And in North America it is already reaping significant benefits. We recycle 376 million pounds of steel annually, and aggressive recycling programs keep 18 million pounds of other scrap materials from landfills. Of course, no one ever said that looking after the Earth's resources is easy. But as we continue to strive for greener ways to do business, there's one thing we're definitely not wasting. And that's time. www.toyota.com/tomorrow ©2001 JUNE 2002 VOLUME 111 NUMBER 5 FEATURES AVIAN QUICK-CHANGE ARTISTS How do house finches thrive in so many environments? By reshaping themselves. -

British Columbia Vegetation and Climate History with Focus on 6 Ka BP

Document generated on 10/01/2021 4:51 p.m. Géographie physique et Quaternaire British Columbia Vegetation and Climate History with Focus on 6 ka BP Histoire du climat et de la végétation de la Colombie-Britannique, notamment de la période de 6 ka BP Geschichte der Vegetation und des Klimas in British Columbia während des Holozäns, besonders um 6 ka v.u.Z. Richard J. Hebda La paléogéographie et la paléoécologie d’il y a 6000 ans BP au Canada Article abstract Paleogeography and Paleoecology of 6000 yr BP in Canada British Columbia Holocene vegetation and climate is reconstructed from pollen Volume 49, Number 1, 1995 records. A coastal Pinus contorta paleobiome developed after glacier retreat under cool and probably dry climate. Cool moist forests involving Picea, Abies, URI: https://id.erudit.org/iderudit/033030ar Tsuga spp., and Pinus followed until the early Holocene. Pseudotsuga menziesii DOI: https://doi.org/10.7202/033030ar arrived and spread in the south 10 000-9000 BP, and Picea sitchensis - Tsuga heterophylla forests developed in the north. T. heterophylla increased 7500-7000 BP, and Cupressaceae expanded 5000-4000 BP. Bogs began to See table of contents develop and expland. Modern vegetation arose 4000-2000 BP. There were early Holocene grass and Artemisia communities at mid-elevations and pine stands at high elevations in southern interior B.C. Forests expanded downslope and Publisher(s) lakes formed 8500-7000 BP. Modern forests arose 4500-4000 BP while lower and upper tree lines declined. In northern B.C. non-arboreal communities Les Presses de l'Université de Montréal preceded middle Holocene Picea forests. -

'The Wesleyan Way'

$2 Annual Conference-July 2011 Season of Pentecost Gadson on ‘audacity of faith’ Page 10 “Are you ready, South Carolina, for what God will do with us together?” Bishop Mary Virginia Taylor asked in the opening service of Annual Conference. (Photos by Jessica Connor) ‘The Wesleyan Way’ a time of worship, of praise, of fellowship the balance between theme and the busi - 31 commissioned United Methodists elect and of legislation. ness of the conference – and not keep peo - or ordained delegates, set budget, Members left Sunday afternoon after ple stuck in business hours after the event Page 2 what Taylor referred to in her closing ser - was slated to close. Key was the shifting pass legislation at 2011 mon as the “great breeze” of the Holy of the final day of business to Saturday Spirit swept through the arena and led the instead of Sunday, and moving the ordina - Annual Conference body to elect delegates to Jurisdictional tion service to the last day of conference and General Conferences in 2012, deter - (Sunday). FLORENCE – “Can you feel it? Can you mine the 2012 conference budget and vote In addition to election for delegates, sense it?” Bishop Mary Virginia Taylor on a host of resolutions. significant this year were a vote on a new, asked members of Annual Conference. Taylor reported at the event’s close that streamlined structure for the Connectional “Are you ready, South Carolina, for what 1,640 members – 846 laity, 795 clergy – Ministries arm of the conference, a shift to God will do with us together?” were in attendance. -

The Oxford Democrat

The Oxford Democrat. NUMBER 49. VOLUME 73. SOUTH PARIS, MAINE, TUESDAY, DECEMBER 4, 1906. '•Say. that's many!" ho cried. "I'c —α shiver that bad la it something Tremalne and I, and I felt myself lbkrt d. park, Have a Feast of Raaaon. May purty nigh fergot It Early this fearfully delightful. And let me add yielding to tlic fascination of the song, γ AMONG THE FAMEES. The foreword In relation to following raorniu' tbey was somebody—a wo here that the emotion which Cecily— even as tbe serpent did. It wtis not Licensed Auctioneer, coarse the Uni- the lecture prepared bj ine and so I came to know her—raised In formi- τω plow." The mm" He came close to for very large, nor seemingly very SOUTH PARIS, MAIMS. "•run versity of Maine along agricultural lines bis voice to a hoarse wbleper. me was not in the least admiration In so I did not even think of fear Housekeepers Term· Moderate. for the present winter shonld be read by dropped dable, r'D' know who I think It was? That the ordinary sense of the term, but when the little door of Correspondence on practical agricultural topics every member of the Grange and other y' Cecily opened In- fascination, when P. BARNES, la solicite· 1. Address all communication· farmers' after which in- Croydon woman!" rather an overpowering tbe cage and drew It forth. She held It have been vexed tended for this to Hkxbt D. organizations, department some amazement such as oue sometimes feels In watch- ^jUARLES Hammond, Editor Oxford Dem fluence should be exerted to secure I stared at blm In between thumb and finger just behind Agricultural back cream of tartar Attorney at Law, ocrai, Paris, lie. -

Slocan Lake 2007 - 2010

BC Lake Stewardship and Monitoring Program Slocan Lake 2007 - 2010 A partnership between the BC Lake Stewardship Society and the Ministry of Environment The Importance of Slocan Lake & its Watershed British Columbians want lakes to provide good water quality, quality of the water resource is largely determined by a water- aesthetics, and recreational opportunities. When these features shed’s capacity to buffer impacts and absorb pollution. are not apparent in our local lakes, people begin to wonder why. Concerns often include whether the water quality is getting Every component of a watershed (vegetation, soil, wildlife, etc.) worse, if the lake has been impacted by land development or has an important function in maintaining good water quality and a other human activities, and what conditions will result from more healthy aquatic environment. It is a common misconception that development within the watershed. detrimental land use practices will not impact water quality if they are kept away from the area immediately surrounding a water- The BC Lake Stewardship Society (BCLSS), in collaboration body. Poor land use practices in a watershed can eventually im- with the Ministry of Environment (MoE), has designed a pro- pact the water quality of the downstream environment. gram, entitled The BC Lake Stewardship and Monitoring Pro- gram, to address these concerns. Through regular water sample Human activities that impact water bodies range from small but collections, we can come to understand a lake's current water widespread and numerous non-point sources throughout the wa- quality, identify the preferred uses for a given lake, and monitor tershed to large point sources of concentrated pollution (e.g. -

Idioms-And-Expressions.Pdf

Idioms and Expressions by David Holmes A method for learning and remembering idioms and expressions I wrote this model as a teaching device during the time I was working in Bangkok, Thai- land, as a legal editor and language consultant, with one of the Big Four Legal and Tax companies, KPMG (during my afternoon job) after teaching at the university. When I had no legal documents to edit and no individual advising to do (which was quite frequently) I would sit at my desk, (like some old character out of a Charles Dickens’ novel) and prepare language materials to be used for helping professionals who had learned English as a second language—for even up to fifteen years in school—but who were still unable to follow a movie in English, understand the World News on TV, or converse in a colloquial style, because they’d never had a chance to hear and learn com- mon, everyday expressions such as, “It’s a done deal!” or “Drop whatever you’re doing.” Because misunderstandings of such idioms and expressions frequently caused miscom- munication between our management teams and foreign clients, I was asked to try to as- sist. I am happy to be able to share the materials that follow, such as they are, in the hope that they may be of some use and benefit to others. The simple teaching device I used was three-fold: 1. Make a note of an idiom/expression 2. Define and explain it in understandable words (including synonyms.) 3. Give at least three sample sentences to illustrate how the expression is used in context. -

The Kootenay Wreck Tour River Above Castlegar

Underwater Archaeological Society of British Columbia Vol. 22 No.6 Nov-Dec 2011 waterfront. The Ymir was made of wood and is 77’ long x 16’ wide x 6’ deep. It was built and launched at Nel‐ son in 1899 and was used to move Transfer barges around. The super structure is gone but the hull, deck planking and boiler are still in place. Directly off the bow of the Ymir is a fifteen car Railway Transfer barge in about 50’ of water. This is a shore dive and the fact that most of the decking is gone means that the inter‐ nal structure of the barge can be seen. This dive site also happens to be the location of the CPR shipways on Kootenay Lake. The CPR fleet of stern‐ wheelers, tugs and Rail barge would have been built and maintained at this location in the late 1800’s up to 1930. Our next site to visit was the Steam Tug Elco II located in the Columbia The Kootenay Wreck Tour River above Castlegar. The Elco II was by, Bill Meekel 76’ long x 15’ wide x 7’ deep. It was built by the Edgewood Lumber Co in In September 2011, eight UASBC concentrates from the mines around 1924 to move log booms on the Arrow members made a visit to the the lake before the railway was in‐ Lakes to their sawmill. The vessel is a Kootenays to visit some of the wrecks stalled. The barge is 197’ long x 33’ shore dive and is upside down on the in the area. -

Corrugated Architecture of the Okanagan Valley Shear Zone and the Shuswap Metamorphic Complex, Canadian Cordillera

Corrugated architecture of the Okanagan Valley shear zone and the Shuswap metamorphic complex, Canadian Cordillera Sarah R. Brown1,2,*, Graham D.M. Andrews1,3, and H. Daniel Gibson2 1DEPARTMENT OF GEOLOGICAL SCIENCES, CALIFORNIA STATE UNIVERSITY–BAKERSFIELD, 9001 STOCKDALE HIGHWAY, BAKERSFIELD, CALIFORNIA 93311, USA 2DEPARTMENT OF EARTH SCIENCE, SIMON FRASER UNIVERSITY, 8888 UNIVERSITY DRIVE, BURNABY, BRITISH COLUMBIA V5A 1S6, CANADA 3DEPARTMENT OF GEOLOGY AND GEOGRAPHY, WEST VIRGINIA UNIVERSITY, 98 BEECHURST AVENUE, MORGANTOWN, WEST VIRGINIA 26506, USA ABSTRACT The distribution of tectonic superstructure across the Shuswap metamorphic complex of southern British Columbia is explained by east-west– trending corrugations of the Okanagan Valley shear zone detachment. Geological mapping along the southern Okanagan Valley shear zone has identified 100-m-scale to kilometer-scale corrugations parallel to the extension direction, where synformal troughs hosting upper-plate units are juxtaposed between antiformal ridges of crystalline lower-plate rocks. Analysis of available structural data and published geological maps of the Okanagan Valley shear zone confirms the presence of≤ 40-km-wavelength corrugations, which strongly influence the surface trace of the detachment system, forming spatially extensive salients and reentrants. The largest reentrant is a semicontinuous belt of late Paleozoic to Mesozoic upper-plate rocks that link stratigraphy on either side of the Shuswap metamorphic complex. Previously, these belts were considered by some to be autochthonous, implying minimal motion on the Okanagan Valley shear zone (≤12 km); conversely, our results suggest that they are allochthonous (with as much as 30–90 km displacement). Corrugations extend the Okanagan Valley shear zone much farther east than previously recognized and allow for hitherto separate gneiss domes and detachments to be reconstructed together to form a single, areally extensive Okanagan Valley shear zone across the Shuswap metamorphic complex. -

An Act Respecting the Nakusp and Slocan Railway

1894. RAILWAY, NAKTJSP AND SLOGAN. CLXAP. 43. CHAPTER 43. An Act respecting the Nakusp and Slocan Railway. [llih April, 189i.} 7HEREAS authority was conferred upon the Lieutenant-Governor Preamble. > in Council by the " Railway Aid Act, 1893," to give a guarantee of interest upon the bonds of (amongst other railways) the Nakusp and Slocan Railway Company, hereinafter called the " Company," to the extent, at the rate, and upon the conditions in said Act specified, and power was also conferred to arrange all details, and to enter into all agreements which might be necessary for cariying out the pro visions of the said Act: And whereas under and in pursuance of the authority conferred by the said Act, the Lieutenant-Governor in Council duly authorized the execution of the several agreements, copies whereof arc set out in the schedule hereto purporting to be executed by the Minister of Finance or the Chief Commissioner of Lands and Works, as the case may be, viz.:— (1.) Agreement dated the 9th day of August, 1893, between the Nakusp and Slocan Railway Company and the Chief Commissioner of Lands and Works; (2.) Agreement dated the 29th day of August, 1893, between the Nakusp and Slocan Railway Company, the Bank of British Columbia, Messrs. WulfFsohn & Bewicke, Limited, and the Minister of Finance. And whereas pursuant to said agreements the Company has by instrument, dated the 16th day of August, 1893, duly assigned to the Chief Commissioner of Lands and Works all benefit and advantage under the agreement with the Canadian Pacific Railway Company, as provided by the first clause of the said agreement of the 9th August, 1893 : 223 CHAP. -

Mount Robson Provincial Park, Draft Background Report

Mount Robson Provincial Park Including Mount Terry Fox & Rearguard Falls Provincial Parks DRAFT BACKGROUND REPORT September, 2006 Ministry of Environment Ministry of Environment BC Parks Omineca Region This page left blank intentionally Acknowledgements This Draft Background Report for Mount Robson Provincial Park was prepared to support the 2006/07 Management Plan review. The report was prepared by consultant Juri Peepre for Gail Ross, Regional Planner, BC Parks, Omineca Region. Additional revisions and edits were performed by consultant Leaf Thunderstorm and Keith J. Baric, A/Regional Planner, Omineca Region. The report incorporates material from several previous studies and plans including the Mount Robson Ecosystem Management Plan, Berg Lake Corridor Plan, Forest Health Strategy for Mount Robson Provincial Park, Rare and the Endangered Plant Assessment of Mount Robson Provincial Park with Management Interpretations, the Robson Valley Land and Resource Management Plan, and the BC Parks website. Park use statistics were provided by Stuart Walsh, Rick Rockwell and Robin Draper. Cover Photo: Berg Lake and the Berg Glacier (BC Parks). Mount Robson Provincial Park, Including Mount Terry Fox & Rearguard Falls Provincial Parks: DRAFT Background Report 2006 Table of Contents Introduction .....................................................................................................................................................1 Park Overview.................................................................................................................................................1 -

Rocky Mountain Birds: Birds and Birding in the Central and Northern Rockies

University of Nebraska - Lincoln DigitalCommons@University of Nebraska - Lincoln Zea E-Books Zea E-Books 11-4-2011 Rocky Mountain Birds: Birds and Birding in the Central and Northern Rockies Paul A. Johnsgard University of Nebraska - Lincoln, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.unl.edu/zeabook Part of the Ecology and Evolutionary Biology Commons, and the Poultry or Avian Science Commons Recommended Citation Johnsgard, Paul A., "Rocky Mountain Birds: Birds and Birding in the Central and Northern Rockies" (2011). Zea E-Books. 7. https://digitalcommons.unl.edu/zeabook/7 This Book is brought to you for free and open access by the Zea E-Books at DigitalCommons@University of Nebraska - Lincoln. It has been accepted for inclusion in Zea E-Books by an authorized administrator of DigitalCommons@University of Nebraska - Lincoln. ROCKY MOUNTAIN BIRDS Rocky Mountain Birds Birds and Birding in the Central and Northern Rockies Paul A. Johnsgard School of Biological Sciences University of Nebraska–Lincoln Zea E-Books Lincoln, Nebraska 2011 Copyright © 2011 Paul A. Johnsgard. ISBN 978-1-60962-016-5 paperback ISBN 978-1-60962-017-2 e-book Set in Zapf Elliptical types. Design and composition by Paul Royster. Zea E-Books are published by the University of Nebraska–Lincoln Libraries. Electronic (pdf) edition available online at http://digitalcommons.unl.edu/zeabook/ Print edition can be ordered from http://www.lulu.com/spotlight/unllib Contents Preface and Acknowledgments vii List of Maps, Tables, and Figures x 1. Habitats, Ecology and Bird Geography in the Rocky Mountains Vegetational Zones and Bird Distributions in the Rocky Mountains 1 Climate, Landforms, and Vegetation 3 Typical Birds of Rocky Mountain Habitats 13 Recent Changes in Rocky Mountain Ecology and Avifauna 20 Where to Search for Specific Rocky Mountain Birds 26 Synopsis of Major Birding Locations in the Rocky Mountains Region U.S.