Marlboro College, a Memoir Tom Ragle, President Emeritus

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Fall 2014 Landscape Magazine

Landscape Summer/Fall 2014 FOR ALUMNI AND FRIENDS OF LANDMARK COLLEGE Uncut Diamonds Landmark College’s first national fundraising event, featuring Whoopi Goldberg, alumni tributes, and more! Page 9 Russell Cosby ’99 shares the Cosby family’s Landmark College connections. Page 10 SUCCEEDING ON THE SPECTRUM Page 5 CLASS NOTES What’s new with THE ARTS our alumni ARE ALIVE Page 28 AT LC Page 16 From the Desk of Dr. Peter Eden President of Landmark College Dear Alumni and Friends of Landmark College, Our College opened its doors to students 29 years ago. Over these years we have driven change, and we have adapted to changes in higher education and in the LD field; we have faced and overcome significant challenges, and we have seen life-altering outcomes from our students. Throughout our history, Landmark College (LC) has succeeded because we have one of the most operational missions in higher education. Every day, we work to transform the way students learn, educators teach, and the public thinks about education, to ensure that students who learn and operate differently due to LD achieve their greatest potential. We deliberately engineer our efforts, initiatives, programs, curriculum, and strategic Landmark College planning to LD-related needs and opportunities. Indeed, we often feel that everything we do is a highly adaptable, must be directly connected to LD. But this is not necessary. While LD defines us, we must have the courage to not feel that everything we plan and do at the College involves LD. progressive institution This summer, for example, we are starting construction on the new Nicole Goodner BOARD OF TRUSTEES EMERITUS MEMBERS with a student body that MacFarlane Science, Technology & Innovation Center in order to offer the best physical Robert Lewis, M.A., Chair Robert Munley, Esq. -

States of Incarceration and Subordination in the Learning and Lived Experiences of Youth in a Juvenile Detention Facility

ARE THE[SE] KIDS ALRIGHT?: STATES OF INCARCERATION AND SUBORDINATION IN THE LEARNING AND LIVED EXPERIENCES OF YOUTH IN A JUVENILE DETENTION FACILITY by Jonathan Patrick Arendt A thesis submitted in conformity with the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy Graduate Department of Curriculum, Teaching, and Learning Ontario Institute for Studies in Education University of Toronto © Copyright by Jonathan Patrick Arendt 2012 ARE THE[SE] KIDS ALRIGHT?: STATES OF INCARCERATION AND SUBORDINATION IN THE LEARNING AND LIVED EXPERIENCES OF YOUTH IN A JUVENILE DETENTION FACILITY Doctor of Philosophy 2012 Jonathan Patrick Arendt Department of Curriculum, Teaching, and Learning University of Toronto ABSTRACT This study examines the dynamics and implications of trans-spatial subordination in/across the lived experiences of six incarcerated participant youths in a secure custody facility for juveniles in Louisiana. Five male teenagers (four African American, one White) and one female teenager (African American) discuss the limitations, harassment, and confinement in various aspects of their lives and speak about the impact on their expectations for the future. The author employs several methodologies in order to develop a multimedia, multifaceted representation of their lives. The narratives elicited through interviews provide the bulk of the data as the participants describe this perpetual subordination. The photographs, resulting from the implementation of a visual ethnographic methodology, provide images that serve as catalysts for introspection and analysis of significance in the mundane and routine, particularly as they apply to the carceral facilities, structures, and policies themselves. Film viewing and discussion offer an array of depictions of youth and criminality to which the youths responded, granting a simultaneous peek at how these marginalized youths viewed themselves and how mainstream media productions depict them. -

Marlboro College

Potash Hill Marlboro College | Spring 2020 POTASH HILL ABOUT MARLBORO COLLEGE Published twice every year, Marlboro College provides independent thinkers with exceptional Potash Hill shares highlights of what Marlboro College community opportunities to broaden their intellectual horizons, benefit from members, in both undergraduate a small and close-knit learning community, establish a strong and graduate programs, are doing, foundation for personal and career fulfillment, and make a positive creating, and thinking. The publication difference in the world. At our campus in the town of Marlboro, is named after the hill in Marlboro, Vermont, where the college was Vermont, students engage in deep exploration of their interests— founded in 1946. “Potash,” or potassium and discover new avenues for using their skills to improve their carbonate, was a locally important lives and benefit others—in an atmosphere that emphasizes industry in the 18th and 19th centuries, critical and creative thinking, independence, an egalitarian spirit, obtained by leaching wood ash and evaporating the result in large iron and community. pots. Students and faculty at Marlboro no longer make potash, but they are very industrious in their own way, as this publication amply demonstrates. Photo by Emily Weatherill ’21 EDITOR: Philip Johansson ALUMNI DIRECTOR: Maia Segura ’91 CLEAR WRITING STAFF PHOTOGRAPHERS: To Burn Through Where You Are Not Yet BY SOPHIE CABOT BLACK ‘80 Emily Weatherill ’21 and Clement Goodman ’22 Those who take on risk are not those Click above the dial, the deal STAFF WRITER: Sativa Leonard ’23 Who bear it. The sign said to profit Downriver is how you will get paid, DESIGN: Falyn Arakelian Potash Hill welcomes letters to the As they do, trade around the one Later, further. -

AMNH Digital Library

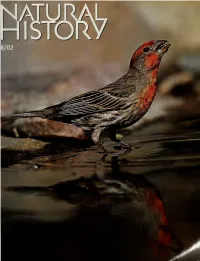

^^<e?& THERE ARE THOSE WHO DO. AND THOSE WHO WOULDACOULDASHOULDA. Which one are you? If you're the kind of person who's willing to put it all on the line to pursue your goal, there's AIG. The organization with more ways to manage risk and more financial solutions than anyone else. Everything from business insurance for growing companies to travel-accident coverage to retirement savings plans. All to help you act boldly in business and in life. So the next time you're facing an uphill challenge, contact AIG. THE GREATEST RISK IS NOT TAKING ONE: AIG INSURANCE, FINANCIAL SERVICES AND THE FREEDOM TO DARE. Insurance and services provided by members of American International Group, Inc.. 70 Pine Street, Dept. A, New York, NY 10270. vww.aig.com TODAY TOMORROW TOYOTA Each year Toyota builds more than one million vehicles in North America. This means that we use a lot of resources — steel, aluminum, and plastics, for instance. But at Toyota, large scale manufacturing doesn't mean large scale waste. In 1992 we introduced our Global Earth Charter to promote environmental responsibility throughout our operations. And in North America it is already reaping significant benefits. We recycle 376 million pounds of steel annually, and aggressive recycling programs keep 18 million pounds of other scrap materials from landfills. Of course, no one ever said that looking after the Earth's resources is easy. But as we continue to strive for greener ways to do business, there's one thing we're definitely not wasting. And that's time. www.toyota.com/tomorrow ©2001 JUNE 2002 VOLUME 111 NUMBER 5 FEATURES AVIAN QUICK-CHANGE ARTISTS How do house finches thrive in so many environments? By reshaping themselves. -

The Allman Betts Band Your Heroes It’S a Dream Come True, but Sat

Locally Owned and Operated Vol. 19 - Issue 7 • July 3, 2019 - August 7, 2019 INSIDE: WINERY GUIDE Vintage Ohio 25th Anniversary! Amphicar Festival July 24-28 2019 Summer Festivals Blues News Movie & Concert Reviews Est. 2000 FREE! Entertainment, Dining & Leisure Connection Read online at www.northcoastvoice.com North Coast Voice OLD FIREHOUSE 5499 Lake RoadWINERY East • Geneva-on-the Lake, Ohio Restaurant & Tasting Room Open 7 days Noon to Midnight Live entertainment 7 days a week! Tasting Rooms Entertainment See inside back cover for listing. all weekend. (see ad on pg. 7) 1-800-Uncork-1 FOR ENTERTAINMENT AND Hours: EVENTS, SEE OUR AD ON PG. 7 Monday Closed Hours: Tues thru Thurs noon to 7 pm, Mon. 12-4 • Tues. Closed Fri and Sat noon to 11 pm, Wed. 12-7 • Thurs. 12-8 Sunday noon to 7 pm Fri. 12-9 • Sat. 12-10 • Sun. 12-5 834 South County Line Road 6451 N. RIVER RD., HARPERSIELD, OHIO 4573 Rt. 307 East, Harpersfield, Oh Harpersfield, Ohio 44041 WED. & THURS, 12 - 7, FRI. 12-9 440.415.0661 440.361.3049 SAT. 12- 9, SUN. 12-6 www.laurellovineyards.com www.bennyvinourbanwinery.com WWW.HUNDLEY CELLARS.COM [email protected] [email protected] If you’re in the mood for a palate pleasing wine tasting accompanied by a delectable entree from our restaurant, Ferrante Winery and Ristorante is the place for you! Entertainment every weekend Hours see ad on pg. 6 Stop and try our New Menu! Tasting Room: Mon. & Tues. 10-5 1520 Harpersfield Road Wed. & Thurs. 10-8, Fri. -

Faculty Faculty Faculty JACQUES N

Faculty Faculty Faculty JACQUES N. BENEAT (2002) Professor of Electrical and Computer Engineering (2015); DEA 1990, Universite Faculty de Brest; Ph.D. 1993 Worcester Polytechnic Institute; Doctorate 1994, Universite de Bordeaux. The year after a name indicates the year hired at Norwich University; the date after the academic title COREY BENNETT (2019) Lecturer of Nursing (2019); indicates the year of that title; the year after each A.S.N. 2011, Castleton State College; B.S.N. 2018, degree indicates the year the degree was earned. University of Vermont; M.S.N. 2019, Norwich University; Registered Nurse. JONATHAN C. ADKINS (2021) Assistant Professor of Cybersecurity (2021); B.S., University of Central KYLIE BLODGETT (2016) Senior Lecturer Physical Florida; M.S., University of Central Florida; Ph.D., Nova Education (2021); B.S. 2010, Norwich University; M.S. Southeastern Univeristy in Ft. Lauderdale, FL. 2011, University of Michigan. M.S. 2015, University of New Hampshire; PhD. 2020, Walden University. MARIE AGAN (2018) Lecturer in Chemistry (2018); B.S. 2011, Saint Michael's College. DAVID J. BLYTHE (1991) Director of the School of Business (2016); Associate Professor of Management DEBORAH AHLERS (1991) Head of Cataloging and (2010); B.S. 1981, Rutgers University; J.D. 1986, Vermont Interlibrary Loan; Assistant Professor (1991); B.A., 1989, Law School. SUNY Binghamton; M.L.S., 1991, SUNY Albany. MATTHEW W. BOVEE (2010) Associate Professor of DANIEL P. ALCORN (2010) Assistant Professor (2020): Computer Science (2019); B.S. 1981, Arizona State A.A. 2008, Kent State University; B.A. 2009, Kent State University; M.A. 1986, The University of Kansas; MSISA University; Program Manager, Bachelor of Science in 2018, Norwich University; Ph.D. -

'The Wesleyan Way'

$2 Annual Conference-July 2011 Season of Pentecost Gadson on ‘audacity of faith’ Page 10 “Are you ready, South Carolina, for what God will do with us together?” Bishop Mary Virginia Taylor asked in the opening service of Annual Conference. (Photos by Jessica Connor) ‘The Wesleyan Way’ a time of worship, of praise, of fellowship the balance between theme and the busi - 31 commissioned United Methodists elect and of legislation. ness of the conference – and not keep peo - or ordained delegates, set budget, Members left Sunday afternoon after ple stuck in business hours after the event Page 2 what Taylor referred to in her closing ser - was slated to close. Key was the shifting pass legislation at 2011 mon as the “great breeze” of the Holy of the final day of business to Saturday Spirit swept through the arena and led the instead of Sunday, and moving the ordina - Annual Conference body to elect delegates to Jurisdictional tion service to the last day of conference and General Conferences in 2012, deter - (Sunday). FLORENCE – “Can you feel it? Can you mine the 2012 conference budget and vote In addition to election for delegates, sense it?” Bishop Mary Virginia Taylor on a host of resolutions. significant this year were a vote on a new, asked members of Annual Conference. Taylor reported at the event’s close that streamlined structure for the Connectional “Are you ready, South Carolina, for what 1,640 members – 846 laity, 795 clergy – Ministries arm of the conference, a shift to God will do with us together?” were in attendance. -

1 TEST OPTIONAL COLLEGES the Colleges Named Below Are SAT/ACT Optional Or Flexible, Meaning That They Minimize Or Eliminate

TEST OPTIONAL COLLEGES The colleges named below are SAT/ACT Optional or Flexible, meaning that they minimize or eliminate the importance of standardized tests in the admissions process. ARHS students regularly apply to these colleges, excerpted from a longer list at www.fairtest.org. That website also contains many religious colleges, art schools, music conservatories and many state campuses. Consult the website for the complete list. Some colleges will consider scores if you send them and others will ignore them if they do not enhance your application. Visit individual college websites to learn about their test-optional policies. Due to NCAA requirements, athletes hoping to participate at Division I and II colleges must submit SAT or ACT scores to all colleges. Key: 3 = SAT/ACT used only when minimum GPA and/or class rank is not met 4 = SAT/ACT required for some programs 5 = Test Flexible: SAT/ACT not required if submit Subject Test, Advanced Placement, Int'l Baccalaureate, other exams or graded writing samples. American International College, Springfield, MA American University, Washington, D.C. Assumption College, Worcester, MA Baldwin-Wallace College, Berea, OH Bard College, Annandale-on-Hudson, NY Bates College, Lewiston, ME Beloit college, Beloit, WI Benjamin Franklin Institute of Technology, Boston, MA Bennington College, Bennington, VT Bowdoin College, Brunswick, ME Brandeis University, Waltham, MA;5 Bridgewater State University, Bridgewater, MA Bryant University, Smithfield, RI Bryn Mawr College, Bryn Mawr, PA Castleton University, -

The Oxford Democrat

The Oxford Democrat. NUMBER 49. VOLUME 73. SOUTH PARIS, MAINE, TUESDAY, DECEMBER 4, 1906. '•Say. that's many!" ho cried. "I'c —α shiver that bad la it something Tremalne and I, and I felt myself lbkrt d. park, Have a Feast of Raaaon. May purty nigh fergot It Early this fearfully delightful. And let me add yielding to tlic fascination of the song, γ AMONG THE FAMEES. The foreword In relation to following raorniu' tbey was somebody—a wo here that the emotion which Cecily— even as tbe serpent did. It wtis not Licensed Auctioneer, coarse the Uni- the lecture prepared bj ine and so I came to know her—raised In formi- τω plow." The mm" He came close to for very large, nor seemingly very SOUTH PARIS, MAIMS. "•run versity of Maine along agricultural lines bis voice to a hoarse wbleper. me was not in the least admiration In so I did not even think of fear Housekeepers Term· Moderate. for the present winter shonld be read by dropped dable, r'D' know who I think It was? That the ordinary sense of the term, but when the little door of Correspondence on practical agricultural topics every member of the Grange and other y' Cecily opened In- fascination, when P. BARNES, la solicite· 1. Address all communication· farmers' after which in- Croydon woman!" rather an overpowering tbe cage and drew It forth. She held It have been vexed tended for this to Hkxbt D. organizations, department some amazement such as oue sometimes feels In watch- ^jUARLES Hammond, Editor Oxford Dem fluence should be exerted to secure I stared at blm In between thumb and finger just behind Agricultural back cream of tartar Attorney at Law, ocrai, Paris, lie. -

Idioms-And-Expressions.Pdf

Idioms and Expressions by David Holmes A method for learning and remembering idioms and expressions I wrote this model as a teaching device during the time I was working in Bangkok, Thai- land, as a legal editor and language consultant, with one of the Big Four Legal and Tax companies, KPMG (during my afternoon job) after teaching at the university. When I had no legal documents to edit and no individual advising to do (which was quite frequently) I would sit at my desk, (like some old character out of a Charles Dickens’ novel) and prepare language materials to be used for helping professionals who had learned English as a second language—for even up to fifteen years in school—but who were still unable to follow a movie in English, understand the World News on TV, or converse in a colloquial style, because they’d never had a chance to hear and learn com- mon, everyday expressions such as, “It’s a done deal!” or “Drop whatever you’re doing.” Because misunderstandings of such idioms and expressions frequently caused miscom- munication between our management teams and foreign clients, I was asked to try to as- sist. I am happy to be able to share the materials that follow, such as they are, in the hope that they may be of some use and benefit to others. The simple teaching device I used was three-fold: 1. Make a note of an idiom/expression 2. Define and explain it in understandable words (including synonyms.) 3. Give at least three sample sentences to illustrate how the expression is used in context. -

COMING FULL CIRCLE Page 2

Fall 2016 LandscapeFor Alumni and Friends of Landmark College COMING FULL CIRCLE Page 2 Rae Jacobson ’06 talks about her ongoing journey of self-discovery and professional success. LC’S SCHOLARSHIP FUND GALA Page 10 FIRST CLASS OF LC BACCALAUREATES Page 14 30TH ANNIVERSARY Page 20 Landmark College’s mission is to transform the way students learn, educators teach, and the public thinks about education. BOARD OF TRUSTEES EMERITUS MEMBERS TABLE OF CONTENTS Robert Lewis, M.A., Chair Robert Munley, Esq. Partner, CKL2 Strategic Partners, LLC Partner, Munley Law Francis Fairman, M.B.A., Vice Chair John Perkins, Esq. Head of Public Finance Service, Palmer & Dodge (retired) Piper Jaffray & Co. 2 Coming Full Circle: Rae Jacobson ‘06 Charles Strauch, B.S. Robert Banta, Esq. Owner, GA Services 8 A New Era for Athletics and Wellness at LC Banta Immigration Law LTD William Cotter, Esq. COLLEGE ADMINISTRATION Retired Owner, Food Manufacturing Business 10 “Unlocking Futures” Scholarship Fund Gala Peter Eden, Ph.D. Robin Dahlberg, Esq. President 14 LC’s First Baccalaureate Graduates Documentary Photographer Manju Banerjee, Ph.D. Peter Eden, Ph.D. Vice President for Educational 15 Donor Profile: Theo van Roijen ’00 President, Landmark College Research and Innovation Jane Garzilli, Esq. Corinne Bell, M.B.A. 16 Faces of Landmark College President, Garzilli Mediation Chief Technology Officer and Bretton Himsworth, B.S. ’90 Director of IT 19 Alumni Advisory Board Director, CentralEd Mark DiPietro, B.A. Linda Kaboolian, Ph.D. Director of Marketing and 20 30th Anniversary Celebration Lecturer, Kennedy School of Government, Communications Harvard University 24 Supporting Innovation Grants John D. -

President's Newsletter • Summer 2019

PRESIDENT’S NEWSLETTER • SUMMER 2019 1 Contents “I bet if you ask any of our graduates what they plan to do once they leave Castleton, they will describe detailed aspirations on the path to dream fulfillment. This generation of Spartans refuses to settle for INTRODUCTION 4 mediocrity. They own the passion and drive to create MESSAGE FROM PRESIDENT SCOLFORO change in this world, and they will not stop until ACADEMIC AFFAIRS 6 OUR 232ND COMMENCEMENT COSTA RICA they see the great things they are capable of come SUNY MUSIC PARTNERSHIP NURSING PARTNERSHIP to fruition. I believe in the future they are so intent FACULTY FELLOW AN INTERNATIONAL EXCHANGE to build, and I have great optimism because of what ADVANCEMENT 13 WELCOME JAMES LAMBERT this class has already helped to accomplish. We CASTLETON GALA ALUMNI SPOTLIGHT often tell students to make a difference here before SUMMER CONCERTS STUDENT LIFE 18 they go out and make a difference in the world, and STUDENT AWARDS CEREMONY ACTIVE MINDS these graduates have done just that.” SPRING SPORTS RECAP DR. KAREN M. SCOLFORO, PRESIDENT 2019 COMMENCEMENT ADDRESS 2 3 Chamber of Commerce networking event, Vermont Governor’s Institute of the Arts, various high school state championships, and the Shrine Maple Sugar Bowl, which returns to Castleton for the fifth straight year on August 3. I want to extend a special thank you to our hardworking facilities crew members, who work tirelessly to keep our beautiful campus looking its best for our visitors, families, and future students. One of my favorite things about the summer quarterly newsletter is it allows me to reflect on the academic year, which always passes too quickly.