Meanings of Worship in Wooden Architecture in Brick

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

To Search High and Low: Liang Sicheng, Lin Huiyin, and China's

Scapegoat Architecture/Landscape/Political Economy Issue 03 Realism 30 To Search High and Low: Liang Sicheng, Lin Huiyin, and China’s Architectural Historiography, 1932–1946 by Zhu Tao MISSING COMPONENTS Living in the remote countryside of Southwest Liang and Lin’s historiographical construction China, they had to cope with the severe lack of was problematic in two respects. First, they were financial support and access to transportation. so eager to portray China’s traditional architec- Also, there were very few buildings constructed ture as one singular system, as important as the in accordance with the royal standard. Liang and Greek, Roman and Gothic were in the West, that his colleagues had no other choice but to closely they highly generalized the concept of Chinese study the humble buildings in which they resided, architecture. In their account, only one dominant or others nearby. For example, Liu Zhiping, an architectural style could best represent China’s assistant of Liang, measured the courtyard house “national style:” the official timber structure exem- he inhabited in Kunming. In 1944, he published a plified by the Northern Chinese royal palaces and thorough report in the Bulletin, which was the first Buddhist temples, especially the ones built during essay on China’s vernacular housing ever written the period from the Tang to Jin dynasties. As a by a member of the Society for Research in Chi- consequence of their idealization, the diversity of nese Architecture.6 Liu Dunzhen, director of the China’s architectural culture—the multiple con- Society’s Literature Study Department and one of struction systems and building types, and in par- Liang’s colleagues, measured his parents’ country- ticular, the vernacular buildings of different regions side home, “Liu Residence” in Hunan province, in and ethnic groups—was roundly dismissed. -

Umithesis Lye Feedingghosts.Pdf

UMI Number: 3351397 INFORMATION TO USERS The quality of this reproduction is dependent upon the quality of the copy submitted. Broken or indistinct print, colored or poor quality illustrations and photographs, print bleed-through, substandard margins, and improper alignment can adversely affect reproduction. In the unlikely event that the author did not send a complete manuscript and there are missing pages, these will be noted. Also, if unauthorized copyright material had to be removed, a note will indicate the deletion. ______________________________________________________________ UMI Microform 3351397 Copyright 2009 by ProQuest LLC All rights reserved. This microform edition is protected against unauthorized copying under Title 17, United States Code. _______________________________________________________________ ProQuest LLC 789 East Eisenhower Parkway P.O. Box 1346 Ann Arbor, MI 48106-1346 TABLE OF CONTENTS ABSTRACT iv ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS vi INTRODUCTION The Yuqie yankou – Present and Past, Imagined and Performed 1 The Performed Yuqie yankou Rite 4 The Historical and Contemporary Contexts of the Yuqie yankou 7 The Yuqie yankou at Puti Cloister, Malaysia 11 Controlling the Present, Negotiating the Future 16 Textual and Ethnographical Research 19 Layout of Dissertation and Chapter Synopses 26 CHAPTER ONE Theory and Practice, Impressions and Realities 37 Literature Review: Contemporary Scholarly Treatments of the Yuqie yankou Rite 39 Western Impressions, Asian Realities 61 CHAPTER TWO Material Yuqie yankou – Its Cast, Vocals, Instrumentation -

Foguang Temple 2005-2009 Progress Report

Foguang Temple 2005-2009 Progress Report Wutai Mountain, Shanxi, China In partnership with Shanxi Bureau of Cultural Relics and the Shanxi Institute of Ancient Architectural Conservation GHF Project Directors Ms. Kuanghan Li, Manager, GHF China Mr. Ren Yiming, Conservation Manager, Shanxi Institute July 2009 Executive Summary GHF helped the Shanxi provincial authority secure matching funding from the central government to support the restoration and scientific conservation of the 1,200-year old Foguang Temple at Wutai Mountain, one of China’s five sacred mountains for Buddhism. Over $900,000 in matching cofunding was secured from the Shanxi Provincial government for the work to date, and the Chinese national government is expected to fund approximately US$1.2-1.6 million (RMB10-12 million) for the restoration of the Grand East Hall that is projected to begin in 2010, contingent upon final approvals. Foguang Temple is considered to be the ‘Fountainhead’ of classical Chinese architecture. Built during the Tang Dynasty, Foguang Temple is a tribute to the peak of Buddhist art and architecture from the 9th century. Grand East Hall of Foguang Temple is one of the oldest and most significant extant wooden structures in China; it is one of two last remaining Tang Dynasty Chinese temples. Until GHF’s initiative, Foguang Temple had not been repaired or conserved since the 17th century. The temple suffers extensive structural damages caused by landslide, water damages from leaking roof, pests and foundation settlement; which are threatening to permanently damage Foguang Temple, the last of China’s oldest wooden architectural wonders. GHF carried out a multi-stage program at a total cost of over $1,060,000 to save the Temple Complex: 1) Master Conservation Planning 2) Architecture conservation The Foguang Temple project was completed under a collaborative agreement with Shanxi Institute of Ancient Architecture Conservation and Research (SIAACR). -

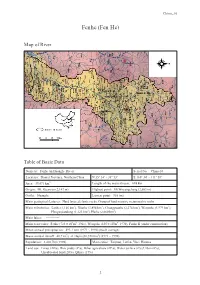

Fenhe (Fen He)

China ―10 Fenhe (Fen He) Map of River Table of Basic Data Name(s): Fenhe (in Huanghe River) Serial No. : China-10 Location: Shanxi Province, Northern China N 35° 34' ~ 38° 53' E 110° 34' ~ 111° 58' Area: 39,471 km2 Length of the main stream: 694 km Origin: Mt. Guancen (2,147 m) Highest point: Mt.Woyangchang (2,603 m) Outlet: Huanghe Lowest point: 365 (m) Main geological features: Hard layered clastic rocks, Group of hard massive metamorphic rocks Main tributaries: Lanhe (1,146 km2), Xiaohe (3,894 km2), Changyuanhe (2,274 km2), Wenyuhe (3,979 km2), Honganjiandong (1,123 km2), Huihe (2,060 km2) Main lakes: ------------ 6 3 6 3 Main reservoirs: Fenhe (723×10 m , 1961), Wenyuhe (105×10 m , 1970), Fenhe II (under construction) Mean annual precipitation: 493.2 mm (1971 ~ 1990) (basin average) Mean annual runoff: 48.7 m3/s at Hejin (38,728 km2) (1971 ~ 1990) Population: 3,410,700 (1998) Main cities: Taiyuan, Linfen, Yuci, Houma Land use: Forest (24%), Rice paddy (2%), Other agriculture (29%), Water surface (2%),Urban (6%), Uncultivated land (20%), Qthers (17%) 3 China ―10 1. General Description The Fenhe is a main tributary of The Yellow River. It is located in the middle of Shanxi province. The main river originates from northwest of Mt. Guanqing and flows from north to south before joining the Yellow River at Wanrong county. It flows through 18 counties and cities, including Ningwu, Jinle, Loufan, Gujiao, and Taiyuan. The catchment area is 39,472 km2 and the main channel length is 693 km. -

82031272.Pdf

journal of palaeogeography 4 (2015) 384e412 HOSTED BY Available online at www.sciencedirect.com ScienceDirect journal homepage: http://www.journals.elsevier.com/journal-of- palaeogeography/ Lithofacies palaeogeography of the Carboniferous and Permian in the Qinshui Basin, Shanxi Province, China * Long-Yi Shao a, , Zhi-Yu Yang a, Xiao-Xu Shang a, Zheng-Hui Xiao a,b, Shuai Wang a, Wen-Long Zhang a,c, Ming-Quan Zheng a,d, Jing Lu a a State Key Laboratory of Coal Resources and Safe Mining, School of Geosciences and Surveying Engineering, China University of Mining and Technology (Beijing), Beijing 100083, China b Hunan Provincial Key Laboratory of Shale Gas Resource Utilization, Hunan University of Science and Technology, Xiangtan 411201, Hunan, China c No.105 Geological Brigade of Qinghai Administration of Coal Geology, Xining 810007, Qinghai, China d Fujian Institute of Geological Survey, Fuzhou 350013, Fujian, China article info abstract Article history: The Qinshui Basin in the southeastern Shanxi Province is an important area for coalbed Received 7 January 2015 methane (CBM) exploration and production in China, and recent exploration has revealed Accepted 9 June 2015 the presence of other unconventional types of gas such as shale gas and tight sandstone Available online 21 September 2015 gas. The reservoirs for these unconventional types of gas in this basin are mainly the coals, mudstones, and sandstones of the Carboniferous and Permian; the reservoir thicknesses Keywords: are controlled by the depositional environments and palaeogeography. This paper presents Palaeogeography the results of sedimentological investigations based on data from outcrop and borehole Shanxi Province sections, and basin-wide palaeogeographical maps of each formation were reconstructed Qinshui Basin on the basis of the contours of a variety of lithological parameters. -

Chinese Religious Art

Chinese Religious Art Chinese Religious Art Patricia Eichenbaum Karetzky LEXINGTON BOOKS Lanham • Boulder • New York • Toronto • Plymouth, UK Published by Lexington Books A wholly owned subsidiary of Rowman & Littlefield 4501 Forbes Boulevard, Suite 200, Lanham, Maryland 20706 www.rowman.com 10 Thornbury Road, Plymouth PL6 7PP, United Kingdom Copyright © 2014 by Lexington Books All rights reserved. No part of this book may be reproduced in any form or by any electronic or mechanical means, including information storage and retrieval systems, without written permission from the publisher, except by a reviewer who may quote passages in a review. British Library Cataloguing in Publication Information Available Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data Karetzky, Patricia Eichenbaum, 1947– Chinese religious art / Patricia Eichenbaum Karetzky. pages cm Includes bibliographical references and index. ISBN 978-0-7391-8058-7 (cloth : alk. paper) — ISBN 978-0-7391-8059-4 (pbk. : alk. paper) — ISBN 978-0-7391-8060-0 (electronic) 1. Art, Chinese. 2. Confucian art—China. 3. Taoist art—China. 4. Buddhist art—China. I. Title. N8191.C6K37 2014 704.9'489951—dc23 2013036347 ™ The paper used in this publication meets the minimum requirements of American National Standard for Information Sciences—Permanence of Paper for Printed Library Materials, ANSI/NISO Z39.48-1992. Printed in the United States of America Contents Introduction 1 Part 1: The Beginnings of Chinese Religious Art Chapter 1 Neolithic Period to Shang Dynasty 11 Chapter 2 Ceremonial -

Hunan Miluo River Disaster Risk Management and Comprehensive Environment Improvement Project

Resettlement Plan (Draft Final) August 2020 People's Republic of China: Hunan Miluo River Disaster Risk Management and Comprehensive Environment Improvement Project Prepared by Pingjiang County Government for the Asian Development Bank CURRENCY EQUIVALENTS (as of 13 July 2020) Currency unit – yuan (CNY) CNY1.00 = $ 0.1430 CNY1.00 = € 0.1264 $1.00 = € 0.8834 €1.00 = $ 1.1430 ABBREVIATIONS ADB Asian Development Bank AAOV average annual output value AP affected persons AHHs affected households DDR Due Diligence Report DI Design Institute DRC Development and Reform Commission DMS Detailed Measurement Survey FSRs Feasibility Study Reports GRM Grievance Redress Mechanism HHPDI Hunan Hydro and Power Design Institute HHs households HD house demolition LA Land Acquisition LAHDC Land Acquisition and Housing Demolition Center of Pingjiang County LLF land-loss farmer M&E Monitoring and Evaluation BNR Natural Resource Bureau of Pingjiang County PLG Project Leading Group PMO Project Management Office PRC People’s Republic of China PCG Pingjiang County Government RP Resettlement Plan RIB Resettlement Information Booklet SPS Safegurad Policy Statement TrTA Transaction Technical Assistance TOR Terms of Reference WEIGHTS AND MEASURES km - kilometer km2 - square kilometer mu - 1/15 hectare m - meter m2 - square meter m3 - cubic meter This resettlement plan is a document of the borrower. The views expressed herein do not necessarily represent those of ADB's Board of Directors, Management, or staff, and may be preliminary in nature. Your attention is directed to the “terms of use” section of this website. In preparing any country program or strategy, financing any project, or by making any designation of or reference to a particular territory or geographic area in this document, the Asian Development Bank does not intend to make any judgments as to the legal or other status of any territory or area. -

Addition of Clopidogrel to Aspirin in 45 852 Patients with Acute Myocardial Infarction: Randomised Placebo-Controlled Trial

Articles Addition of clopidogrel to aspirin in 45 852 patients with acute myocardial infarction: randomised placebo-controlled trial COMMIT (ClOpidogrel and Metoprolol in Myocardial Infarction Trial) collaborative group* Summary Background Despite improvements in the emergency treatment of myocardial infarction (MI), early mortality and Lancet 2005; 366: 1607–21 morbidity remain high. The antiplatelet agent clopidogrel adds to the benefit of aspirin in acute coronary See Comment page 1587 syndromes without ST-segment elevation, but its effects in patients with ST-elevation MI were unclear. *Collaborators and participating hospitals listed at end of paper Methods 45 852 patients admitted to 1250 hospitals within 24 h of suspected acute MI onset were randomly Correspondence to: allocated clopidogrel 75 mg daily (n=22 961) or matching placebo (n=22 891) in addition to aspirin 162 mg daily. Dr Zhengming Chen, Clinical Trial 93% had ST-segment elevation or bundle branch block, and 7% had ST-segment depression. Treatment was to Service Unit and Epidemiological Studies Unit (CTSU), Richard Doll continue until discharge or up to 4 weeks in hospital (mean 15 days in survivors) and 93% of patients completed Building, Old Road Campus, it. The two prespecified co-primary outcomes were: (1) the composite of death, reinfarction, or stroke; and Oxford OX3 7LF, UK (2) death from any cause during the scheduled treatment period. Comparisons were by intention to treat, and [email protected] used the log-rank method. This trial is registered with ClinicalTrials.gov, number NCT00222573. or Dr Lixin Jiang, Fuwai Hospital, Findings Allocation to clopidogrel produced a highly significant 9% (95% CI 3–14) proportional reduction in death, Beijing 100037, P R China [email protected] reinfarction, or stroke (2121 [9·2%] clopidogrel vs 2310 [10·1%] placebo; p=0·002), corresponding to nine (SE 3) fewer events per 1000 patients treated for about 2 weeks. -

Timber Use in the Chinese Gardens and Architecture

Timber Use in the Chinese Gardens and Architecture 木材在中国园林及建筑中的应用 Ying JIANG 2012.05 CAUPD CAUPD • 1、Reasons why timber constructions appear and become mainstream in China • 为什么中国会发展出木结构建筑并形成主流 • 2 The development of timber constructions in ancient China • 木结构建筑在中国古代的发展 • 3 The development of timber constructions in ancient China • 木结构建筑在中国近现代的发展 • 4 The advantages of timber • 木材的优点 • 5 Conclusion • 结语 CAUPD • 1、Reasons why timber constructions appear and become mainstream in China • 为什么中国会发展出木结构建筑并形成主流 In the ancient times, the weather and geographical condition is suitable for growing Climate plants in the Yellow River basin. 气候 Hydrology 水文 Geography The dense forest and river here make it easy to get raw 地理 materials and transport them. CAUPD • 1、Reasons why timber constructions appear and become mainstream in China • 为什么中国会发展出木结构建筑并形成主流 Cutting easy Timber becomes 采伐容易 the first choice to build houses processing easy because it is lighter 加工容易 and more easily to cut and process. Light weight 重量轻 Mining hard 开采困难 processing hard 加工困难 heavy weight 重量沉 CAUPD • 1、Reasons why timber constructions appear and become mainstream in China • 为什么中国会发展出木结构建筑并形成主流 The Chinese philosophy- Taoism believes that the basic substances metal that compose the world are metal, wood, water, fire and soil, and each of them corresponds to one of the five direction. Soil represents Central on behalf of the load of all earth things and soil would have a earth water high status. Five elements of wood represent east and symbol of spring and vitality; while Gold acting on behalf of the West and a symbol of force and punishment to kill; water, fire for the intangible thing, therefore, the five elements fire wood represent the most advocates of the five substances, only "soil" and "wood" is the most suitable for the construction of housing people live. -

中国砂梨出口美国注册包装厂名单(20180825更新) Registered Packinghouses of Fresh Chinese Sand Pears to U.S

中国砂梨出口美国注册包装厂名单(20180825更新) Registered Packinghouses of Fresh Chinese Sand Pears to U.S. 序号 所在地 Location: County, 包装厂中文名 包装厂英文名 包装厂中文地址 包装厂英文地址 注册登记号 Number Location Province Chinese Name of Packing house English Name of Packing house Address in Chinese Address in English Registered Number 辛集市裕隆保鲜食品有限责任公 XINJI YULONG FRESH FOOD CO.,LTD. 1 河北辛集 XINJI,HEBEI 河北省辛集市南区朝阳路19号 NO.19 CHAOYANG ROAD,XINJI,HEBEI 1300GC001 司果品包装厂 PACKING HOUSE 2 河北辛集 XINJI,HEBEI 河北天华实业有限公司 HEBEI TIANHUA ENTERPRISE CO.,LTD. 河北省辛集市新垒头村 XINLEITOU VILLAGE,XINJI CITY, HEBEI 1300GC002 TONGDA ROAD, JINZHOU CITY,HEBEI 3 河北晋州 JINZHOU,HEBEI 晋州天洋贸易有限公司 JINZHOU TIANYANG TRADE CO.,LTD. 河北省晋州市通达路 1300GC005 PROVINCE HEBEI JINZHOU GREAT WALL ECONOMY 4 河北晋州 JINZHOU,HEBEI 河北省晋州市长城经贸有限公司 河北省晋州市马于开发区 MAYU,JINZHOU,HEBEI,CHINA 1300GC006 TRADE CO.,LTD. TIANJIAZHUANG INDUSTRIAL DEVELOPMENT 5 河北辛集 XINJI,HEBEI 辛集市天宇包装厂 XINJI TIANYU PACKING HOUSE 辛集市田家庄乡工业开发区 1300GC009 ZONE,XINJI,HEBEI HEBEI YUETAI AGRICULTURAL PRODUCTS TEXTILE INDUSTRIAL PARK,JINZHOU,HEBEI, 6 河北晋州 JINZHOU,HEBEI 河北悦泰农产品加工有限公司 河北省晋州市纺织园区 1300GC036 PROCESSING CO.,LTD. CHINA 7 河北泊头 BOTOU,HEBEI 泊头东方果品有限公司 BOTOU DONGFANG FRUIT CO.,LTD. 泊头河西金马小区 HEXI JINMA SMALL SECTION, BOTOU CITY 1306GC001 8 河北泊头 BOTOU,HEBEI 泊头亚丰果品有限公司 BOTOU YAFENG FRUIT CO., LTD. 泊头市齐桥镇 QIQIAO TOWN, BOTOU CITY 1306GC002 9 河北泊头 BOTOU,HEBEI 泊头食丰果品有限责任公司 BOTOU SHIFENG FRUIT CO., LTD. 泊头市齐桥镇大炉村 DALU VILLAGE,QIQIAO TOWN, BOTOU CITY 1306GC003 HEJIAN ZHONGHONG AGRICULTURE NANBALIPU VILLAGE, LONGHUADIAN TOWN, 10 河北河间 HEJIAN,HEBEI 河间市中鸿农产品有限公司 河间市龙华店乡南八里铺 1306GC005 PRODUCTS CO.,LTD. HEJIAN CITY 11 河北泊头 BOTOU,HEBEI 沧州金马果品有限公司 CANGZHOU JINMA FRUIT CO.,LTD. 泊头市龙华街 LONGHUA STREET,BOTOU CITY 1306GC018 SHEN VILLAGE, GUXIAN TOWN, QIXIAN, 12 山西晋中市 JINZHONG,SHANXI 祁县耀华果业有限公司 QIXIAN YAOHUA FRUIT CO., LTD 山西省晋中市祁县古县镇申村 1400GC020 JINZHONG, SHANXI 山西省晋中市祁县昭馀镇西关村西 SOUTHWESTERN ALLEY, XIGUAN VILLAGE, 13 山西晋中市 JINZHONG,SHANXI 祁县麒麟果业有限公司 QIXIAN QILIN FRUIT CO., LTD. -

RELACION DE LUGARES DE PRODUCCION AUTORIZADOS a EXPORTAR MANZANAS (Malus Domestica) AL PERU

RELACION DE LUGARES DE PRODUCCION AUTORIZADOS A EXPORTAR MANZANAS (Malus domestica) AL PERU 2019-2020年中国苹果输往秘鲁注册果园名单 LIST OF REGISTERED ORCHARDS FOR APPLES EXPORTING TO PURE IN THE YEAR OF 2019-2020 所在地中文名 果园中文名称 注册登记号 序号 所在地英文名 Location 果园英文名称 中文地址 英文地址 Location Orchard Name Registered No. (English) Orchard Name (English) Address (Chinese) Address (English) (Chinese) (Chinese) Code TIANHUYU VILLAGE, GREAT WALL APPLE 石家庄市井陉矿区贾庄镇 JIAZHUANG TOWN, 1 河北 JINGXING,HEBEI 长城苹果园 1300GY028 ORCHARD 天户屿村 JINGXING DISTRICT, SHIJIAZHUANG CITY SHUIYU VILLAGE, 山西省运城市芮城县学张 XUEZHANG TOWN, 2 山西运城 YUNCHENG,SHANXI 条山果园 TIAO MOUNTAIN ORCHARD RUICHENG COUNTY, 0507GY0027 乡水峪村 YUNCHENG CITY, SHANXI PROVINCE PEIZHUANG TOWN, 山西省运城市万荣县裴庄 WANRONG COUNTY, 3 山西运城 YUNCHENG,SHANXI 裴庄果园 PEIZHUANG ORCHARD 0507GY0104 乡 YUNCHENG CITY, SHANXI PROVINCE , 山西省运城市临猗县猗氏 YISHI TOWN LINYI 4 山西运城 YUNCHENG,SHANXI 孙家卓果园 SUNJIAZHUO ORCHARD COUNTY, YUNCHENG CITY, 0507GY0153 镇 SHANXI PROVINCE XIQI VILLAGE, BUGUAN 山西省运城市平陆县部官 TOWN, PINGLU COUNTY, 5 山西运城 YUNCHENG,SHANXI 西祁果园 XIQI ORCHARD 0507GY0017 镇西祁村 YUNCHENG CITY, SHANXI PROVINCE FENGWANG ROAD QIJI 山西省运城市临猗七级冯 TOWN LINYI COUNTY 6 山西运城 YUNCHENG,SHANXI 七级镇果园 QIJI TOWNSHIP ORCHARD 0507GY0159 王路 1 号 YUNCHENG CITY SAHNXI PROVINCE RELACION DE LUGARES DE PRODUCCION AUTORIZADOS A EXPORTAR MANZANAS (Malus domestica) AL PERU JIACUN VILLAGE, TONGAI HONGYAN APPLE 山西省运城市万荣县贾村 TOWN, WANRONG CONTRY, 7 山西运城 YUNCHENG,SHANXI 红艳苹果园 0507GY0235 ORCHARD 乡贾村 YUNCHENG CITY, SHANXI PROVINCE. SUNJIAZHUANG VILLAGE, 山西省运城市万荣县贾村 JIACUN TOWN, WANRONG 8 山西运城 YUNCHENG,SHANXI -

Transport Corridors and Regional Balance in China: the Case of Coal Trade and Logistics Chengjin Wang, César Ducruet

Transport corridors and regional balance in China: the case of coal trade and logistics Chengjin Wang, César Ducruet To cite this version: Chengjin Wang, César Ducruet. Transport corridors and regional balance in China: the case of coal trade and logistics. Journal of Transport Geography, Elsevier, 2014, 40, pp.3-16. halshs-01069149 HAL Id: halshs-01069149 https://halshs.archives-ouvertes.fr/halshs-01069149 Submitted on 28 Sep 2014 HAL is a multi-disciplinary open access L’archive ouverte pluridisciplinaire HAL, est archive for the deposit and dissemination of sci- destinée au dépôt et à la diffusion de documents entific research documents, whether they are pub- scientifiques de niveau recherche, publiés ou non, lished or not. The documents may come from émanant des établissements d’enseignement et de teaching and research institutions in France or recherche français ou étrangers, des laboratoires abroad, or from public or private research centers. publics ou privés. Transport corridors and regional balance in China: the case of coal trade and logistics Dr. Chengjin WANG Key Laboratory of Regional Sustainable Development Modeling Institute of Geographical Sciences and Natural Resources Research Chinese Academy of Sciences, Beijing 100101, China Email: [email protected] Dr. César DUCRUET1 National Centre for Scientific Research (CNRS) UMR 8504 Géographie-cités F-75006 Paris, France Email: [email protected] Pre-final version of the paper published in Journal of Transport Geography, special issue on “The Changing Landscapes of Transport and Logistics in China”, Vol. 40, pp. 3-16. Abstract Coal plays a vital role in the socio-economic development of China. Yet, the spatial mismatch between production centers (inland Northwest) and consumption centers (coastal region) within China fostered the emergence of dedicated coal transport corridors with limited alternatives.