Bone and Blood: the Price of Coal in China

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Fenhe (Fen He)

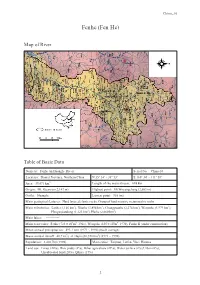

China ―10 Fenhe (Fen He) Map of River Table of Basic Data Name(s): Fenhe (in Huanghe River) Serial No. : China-10 Location: Shanxi Province, Northern China N 35° 34' ~ 38° 53' E 110° 34' ~ 111° 58' Area: 39,471 km2 Length of the main stream: 694 km Origin: Mt. Guancen (2,147 m) Highest point: Mt.Woyangchang (2,603 m) Outlet: Huanghe Lowest point: 365 (m) Main geological features: Hard layered clastic rocks, Group of hard massive metamorphic rocks Main tributaries: Lanhe (1,146 km2), Xiaohe (3,894 km2), Changyuanhe (2,274 km2), Wenyuhe (3,979 km2), Honganjiandong (1,123 km2), Huihe (2,060 km2) Main lakes: ------------ 6 3 6 3 Main reservoirs: Fenhe (723×10 m , 1961), Wenyuhe (105×10 m , 1970), Fenhe II (under construction) Mean annual precipitation: 493.2 mm (1971 ~ 1990) (basin average) Mean annual runoff: 48.7 m3/s at Hejin (38,728 km2) (1971 ~ 1990) Population: 3,410,700 (1998) Main cities: Taiyuan, Linfen, Yuci, Houma Land use: Forest (24%), Rice paddy (2%), Other agriculture (29%), Water surface (2%),Urban (6%), Uncultivated land (20%), Qthers (17%) 3 China ―10 1. General Description The Fenhe is a main tributary of The Yellow River. It is located in the middle of Shanxi province. The main river originates from northwest of Mt. Guanqing and flows from north to south before joining the Yellow River at Wanrong county. It flows through 18 counties and cities, including Ningwu, Jinle, Loufan, Gujiao, and Taiyuan. The catchment area is 39,472 km2 and the main channel length is 693 km. -

Ÿþm Icrosoft W

Copernic Agent Search Results Search: explosion deep mine (All the words) Found: 3464 result(s) on _Full.Search Date: 7/23/2010 10:40:53 AM 1. History Channel Presents: NOSTRADAMUS: 2012 Dec 31, 2008 ... I really want to get these into deeps space because who knows whats ..... what created the molecules or atoms that caused the explosion “big .... A friend of mine emailed me. He asked me if I had see the show on the ... http://ufos.about.com/b/2008/12/31/history-channel-presents-nostradamus-2012.htm 95% 2. Current Netlore - Internet hoaxes, rumors, etc. - A to Z Index, cont. Cell Phones Cause Gas Station Explosions Still unsubstantiated. .... 8-month-old Delaney Parrish, who was seriously burned by hot oil from a Fry Daddy deep fryer in 2001. ..... who lost his leg in a land mine explosion in Afghanistan. ... http://urbanlegends.about.com/library/blxatoz2.htm 94% 3. North Carolina Collection-This Month in North Carolina History - Carolina Coal Company Mine Explosion Sep 2009 - ...Carolina Coal Company Mine Explosion, Coal Glen, North...1925, a massive explosion shook the town of...blast came from the Deep River Coal Field...underground. The explosion, probably touched...descent into the mine on May 31st. Seven... http://www.lib.unc.edu/ncc/ref/nchistory/may2005/index.html 94% 4. Safety comes first at Sugar Creek limestone mine 2010/07/17 The descent takes perhaps 90 seconds. Daylight blinks out, and the speed of the steel cages descent accelerates. Soon, the ears pop slightly. http://www.kansascity.com/2010/07/16/2084075/safety-comes-first-at-sugar-creek.html 94% 5. -

FORUM: Sixth Committee of the General Assembly (Legal)

FORUM: Sixth Committee of the General Assembly (Legal) QUESTION OF: Establishing guidelines to ensure better and safer working conditions in quar- ries and mines STUDENT OFFICER: Jacqueline Schnell POSITION: Main Chair INTRODUCTION "Every coal miner I talked to had, in his history, at least one story of a cave-in. 'Yeah, he got covered up,' is a way coal miners refer to fathers and brothers and sons who got buried alive.“ ~ Jeanne Marie Laskas As stated in the quote above, every miner knows the risks it takes to work in such an industry. Mining has always been a risky occupation, es- pecially in developing na- tions and countries with lax safety standards. Still today, thousands of miners die from mining accidents each year, especially in the pro- cess of coal and hard rock mining, as can be seen in the diagram below. Although the number of deadly Source: see: IX. Useful Links and Sources: XI. Statistics to mine accidents accidents is declining, any fatal accident should still be considered a tragedy, and definitely must be prevented in advance. It seems totally irresponsible and reprehensible that while technological improvements and stricter safety regulations have reduced coal mining related deaths, accidents are still so common, most of them occurring in developing countries. Page 1 of 14 AMUN 2019 – Research Report for the 6th committee Sadly, striving for quick profits in lieu of safety considerations led to several of these tremendous calamities in the near past. Only in Chinese coal mines an average of 13 miners are killed a day. The Benxihu colliery disaster, which is believed to be the worst coal mining disaster in human history, took place in China, as well, and cost 1,549 humans their lives. -

Does Cadre Turnover Help Or Hinder China's Green Rise?

Frankfurt School – Working Paper Series No. 184 Does Cadre Turnover Help or Hinder China’s Green Rise? Evidence from Shanxi Province by Sarah Eaton and Genia Kostka January 2012 Sonnemannstr. 9 – 11 60314 Frankfurt an Main, Germany Phone: +49 (0) 69 154 008 0 Fax: +49 (0) 69 154 008 728 Internet: www.frankfurt-school.de Does Cadre Turnover Help or Hinder China’s Green Rise? Evidence from Shanxi Province Abstract China’s national leaders see restructuring and diversification away from resource- based, energy intensive industries as central goals in the coming years. This paper ar- gues that the high turnover of leading cadres at the local level may hinder state-led greening growth initiatives. Frequent cadre turnover is intended to keep local Party secretaries and mayors on the move in order to curb localism and promote compliance with central directives. Yet, with average term lengths of between three and four years, local leaders’ short time horizons can have the perverse effect of discouraging them from taking on comprehensive restructuring, a costly, complex and lengthy process. On the basis of extensive fieldwork in Shanxi province during 2010 and 2011, the pa- per highlights the salience of frequent leadership turnover for China’s green growth ambitions. Key words: Local state, China, policy implementation, governance, cadre rotation JEL classification: D78, D73, O18, R58, Q48, Q58 ISSN: 14369753 Contact: Prof. Dr. Genia Kostka Dr. Sarah Eaton Dr. Werner Jackstädt Assistant Professor Post-Doctoral Researcher for Chinese Business Studies University of Oxford China Centre East-West Centre of Business Studies 74 Woodstock Road and Cultural Science Oxford, OX2 6HP Frankfurt School of Finance & Management E-Mail: [email protected] Sonnemannstraße 9-11, 60314 Frankfurt am Main Tel.: +49 (0)69 154008- 845 Fax.: +49 (0)69 154008-4845 E-Mail: [email protected] Acknowledgements: Fieldwork for this study was partly funded by the Development Leadership Pro- gram ( www.dlp.org ), Werner Jackstädt Foundation and the Social Sciences and Humanities Research Council. -

Resettlement Monitoring Report: People's Republic of China: Henan

Resettlement Monitoring Report Project Number: 34473 December 2010 PRC: Henan Wastewater Management and Water Supply Sector Project – Resettlement Monitoring Report No. 8 Prepared by: Environment School, Beijing Normal University For: Henan Province Project Management Office This report has been submitted to ADB by Henan Province Project Management Office and is made publicly available in accordance with ADB’s public communications policy (2005). It does not necessarily reflect the views of ADB. Henan Wastewater Management and Water Supply Sector Project Financed by Asian Development Bank Monitoring and Evaluation Report on the Resettlement of Henan Wastewater Management and Water Supply Sector Project (No. 8) Environment School Beijing Normal University, Beijing,China December , 2010 Persons in Charge : Liu Jingling Independent Monitoring and : Liu Jingling Evaluation Staff Report Writers : Liu Jingling Independent Monitoring and : Environment School, Beijing Normal University Evaluation Institute Environment School, Address : Beijing Normal University, Beijing, China Post Code : 100875 Telephone : 0086-10-58805092 Fax : 0086-10-58805092 E-mail : jingling @bnu .edu.cn Content CONTENT ...........................................................................................................................................................I 1 REVIEW .................................................................................................................................................... 1 1.1 PROJECT INTRODUCTION .................................................................................................................. -

Evaluation of Sustainable Development of Resources-Based Cities in Shanxi Province Based on Unascertained Measure

sustainability Article Evaluation of Sustainable Development of Resources-Based Cities in Shanxi Province Based on Unascertained Measure Yong-Zhi Chang and Suo-Cheng Dong * Institute of Geographic Sciences and Natural Resources Research, the Chinese Academy of Sciences, Beijing 100101, China; [email protected] * Correspondence: [email protected]; Tel.: +86-10-64889430; Fax: +86-10-6485-4230 Academic Editor: Marc A. Rosen Received: 31 March 2016; Accepted: 16 June 2016; Published: 22 June 2016 Abstract: An index system is established for evaluating the level of sustainable development of resources-based cities, and each index is calculated based on the unascertained measure model for 11 resources-based cities in Shanxi Province in 2013 from three aspects; namely, economic, social, and resources and environment. The result shows that Taiyuan City enjoys a high level of sustainable development and integrated development of economy, society, and resources and environment. Shuozhou, Changzhi, and Jincheng have basically realized sustainable development. However, Yangquan, Linfen, Lvliang, Datong, Jinzhong, Xinzhou and Yuncheng have a low level of sustainable development and urgently require a transition. Finally, for different cities, we propose different countermeasures to improve the level of sustainable development. Keywords: resources-based cities; sustainable development; unascertained measure; transition 1. Introduction In 1987, the World Commission on Environment and Development (WCED) proposed the concept of “sustainable development”. In 1996, the first official reference to “sustainable cities” was raised at the Second United Nations Human Settlements Conference, namely, as being comprised of economic growth, social equity, higher quality of life and better coordination between urban areas and the natural environment [1]. -

Due Diligence Report on Land Use Rights Transfer and Land Acquisition and Resettlement

Shanxi Inclusive Agricultural Value Chain Development Project (RRP PRC 48358) Due Diligence Report on Land Use Rights Transfer and Land Acquisition and Resettlement Project number: 48358-001 August 2017 People’s Republic of China: Shanxi Inclusive Agricultural Value Chain Development Project Prepared by Zhiyang He for the Asian Development Bank PRC: Shanxi Inclusive Agriculture Value Chain Development Project Due Diligence Report on Land Use Rights Transfer and Land Acquisition and Resettlement (Revised on 25 June 2017) August 2017 Zhiyang He, Land and Resettlement Specialist TABLE OF CONTENTS 1. Introduction .............................................................................................................................. 1 1.1 Project Background ....................................................................................................... 1 1.2 Tasks Assigned and Progress ......................................................................................... 1 1.3 Methodology and approaches ...................................................................................... 1 2. Land Acquisition and Resettlement Impacts Screening ............................................................ 4 2.1 Screening of LAR Impacts .............................................................................................. 4 2.2 Documentation Preparation on LAR ............................................................................. 4 3. Type and Scope of Voluntary Land Use of PACs ....................................................................... -

RPD: People's Republic of China: Shanxi Small Cities and Towns

Resettlement Planning Document Updated Resettlement Plan Document Stage: Final Project Number: 42383 January 2011 People’s Republic of China: Shanxi Small Cities and Towns Development Demonstration Sector Project– Youyu County Subproject Prepared by Youyu County Project Management Office (PMO) The updated resettlement plan is a document of the borrower. The views expressed herein do not necessarily represent those of ADB’s Board of Directors, Management, or staff, and may be preliminary in nature. Resettlement Plan Shanxi Small Cities & Towns Development Demonstration Project Resettlement Plan For Youyu County Subproject Youyu County Development and Reform Bureau 30 September, 2008 Shanxi Urban & Rural Design Institute 1 Youyu County ADB Loan Financed Project Management Office Endorsement Letter of Resettlement Plan Youyu County Government has applied for a loan from the ADB to finance the District Heating, Drainage and wastewater network, River improvement, Roads and Water supply Projects. Therefore, the projects must be implemented in compliance with the guidelines and policies of the Asian Development Bank for Social Safeguards. This Resettlement Plan is in line with the key requirements of the Asian Development Bank and will constitute the basis for land acquisition, house demolition and resettlement of the project. The Plan also complies with the laws of the People’s Republic of China, Shanxi Province and Youyu County regulations, as well as with some additional measures and the arrangements for implementation and monitoring for the purpose of achieving better resettlement results. Youyu County ADB Loan Project Office hereby approves the contents of this Resettlement Plan and guarantees the implementation of land acquisition, house demolition, resettlement, compensation and fund budget will comply with this plan. -

World Bank Document

CONFORMED COPY LOAN NUMBER 7909-CN Public Disclosure Authorized Project Agreement Public Disclosure Authorized (Henan Ecological Livestock Project) between INTERNATIONAL BANK FOR RECONSTRUCTION AND DEVELOPMENT Public Disclosure Authorized and HENAN PROVINCE Dated July 26, 2010 Public Disclosure Authorized PROJECT AGREEMENT AGREEMENT dated July 26, 2010, entered into between INTERNATIONAL BANK FOR RECONSTRUCTION AND DEVELOPMENT (the “Bank”) and HENAN PROVINCE (“Henan” or the “Project Implementing Entity”) (“Project Agreement”) in connection with the Loan Agreement of same date between PEOPLE’S REPUBLIC OF CHINA (“Borrower”) and the Bank (“Loan Agreement”) for the Henan Ecological Livestock Project (the “Project”). The Bank and Henan hereby agree as follows: ARTICLE I – GENERAL CONDITIONS; DEFINITIONS 1.01. The General Conditions as defined in the Appendix to the Loan Agreement constitute an integral part of this Agreement. 1.02. Unless the context requires otherwise, the capitalized terms used in the Project Agreement have the meanings ascribed to them in the Loan Agreement or the General Conditions. ARTICLE II – PROJECT 2.01. Henan declares its commitment to the objective of the Project. To this end, Henan shall: (a) carry out the Project in accordance with the provisions of Article V of the General Conditions; and (b) provide promptly as needed, the funds, facilities, services and other resources required for the Project. 2.02. Without limitation upon the provisions of Section 2.01 of this Agreement, and except as the Bank and Henan shall otherwise agree, Henan shall carry out the Project in accordance with the provisions of the Schedule to this Agreement. ARTICLE III – REPRESENTATIVE; ADDRESSES 3.01. -

82031272.Pdf

journal of palaeogeography 4 (2015) 384e412 HOSTED BY Available online at www.sciencedirect.com ScienceDirect journal homepage: http://www.journals.elsevier.com/journal-of- palaeogeography/ Lithofacies palaeogeography of the Carboniferous and Permian in the Qinshui Basin, Shanxi Province, China * Long-Yi Shao a, , Zhi-Yu Yang a, Xiao-Xu Shang a, Zheng-Hui Xiao a,b, Shuai Wang a, Wen-Long Zhang a,c, Ming-Quan Zheng a,d, Jing Lu a a State Key Laboratory of Coal Resources and Safe Mining, School of Geosciences and Surveying Engineering, China University of Mining and Technology (Beijing), Beijing 100083, China b Hunan Provincial Key Laboratory of Shale Gas Resource Utilization, Hunan University of Science and Technology, Xiangtan 411201, Hunan, China c No.105 Geological Brigade of Qinghai Administration of Coal Geology, Xining 810007, Qinghai, China d Fujian Institute of Geological Survey, Fuzhou 350013, Fujian, China article info abstract Article history: The Qinshui Basin in the southeastern Shanxi Province is an important area for coalbed Received 7 January 2015 methane (CBM) exploration and production in China, and recent exploration has revealed Accepted 9 June 2015 the presence of other unconventional types of gas such as shale gas and tight sandstone Available online 21 September 2015 gas. The reservoirs for these unconventional types of gas in this basin are mainly the coals, mudstones, and sandstones of the Carboniferous and Permian; the reservoir thicknesses Keywords: are controlled by the depositional environments and palaeogeography. This paper presents Palaeogeography the results of sedimentological investigations based on data from outcrop and borehole Shanxi Province sections, and basin-wide palaeogeographical maps of each formation were reconstructed Qinshui Basin on the basis of the contours of a variety of lithological parameters. -

Henan Wastewater Management and Water Supply Sector Project (11 Wastewater Management and Water Supply Subprojects)

Environmental Assessment Report Summary Environmental Impact Assessment Project Number: 34473-01 February 2006 PRC: Henan Wastewater Management and Water Supply Sector Project (11 Wastewater Management and Water Supply Subprojects) Prepared by Henan Provincial Government for the Asian Development Bank (ADB). The summary environmental impact assessment is a document of the borrower. The views expressed herein do not necessarily represent those of ADB’s Board of Directors, Management, or staff, and may be preliminary in nature. CURRENCY EQUIVALENTS (as of 02 February 2006) Currency Unit – yuan (CNY) CNY1.00 = $0.12 $1.00 = CNY8.06 The CNY exchange rate is determined by a floating exchange rate system. In this report a rate of $1.00 = CNY8.27 is used. ABBREVIATIONS ADB – Asian Development Bank BOD – biochemical oxygen demand COD – chemical oxygen demand CSC – construction supervision company DI – design institute EIA – environmental impact assessment EIRR – economic internal rate of return EMC – environmental management consultant EMP – environmental management plan EPB – environmental protection bureau GDP – gross domestic product HPG – Henan provincial government HPMO – Henan project management office HPEPB – Henan Provincial Environmental Protection Bureau HRB – Hai River Basin H2S – hydrogen sulfide IA – implementing agency LEPB – local environmental protection bureau N – nitrogen NH3 – ammonia O&G – oil and grease O&M – operation and maintenance P – phosphorus pH – factor of acidity PMO – project management office PM10 – particulate -

Table of Codes for Each Court of Each Level

Table of Codes for Each Court of Each Level Corresponding Type Chinese Court Region Court Name Administrative Name Code Code Area Supreme People’s Court 最高人民法院 最高法 Higher People's Court of 北京市高级人民 Beijing 京 110000 1 Beijing Municipality 法院 Municipality No. 1 Intermediate People's 北京市第一中级 京 01 2 Court of Beijing Municipality 人民法院 Shijingshan Shijingshan District People’s 北京市石景山区 京 0107 110107 District of Beijing 1 Court of Beijing Municipality 人民法院 Municipality Haidian District of Haidian District People’s 北京市海淀区人 京 0108 110108 Beijing 1 Court of Beijing Municipality 民法院 Municipality Mentougou Mentougou District People’s 北京市门头沟区 京 0109 110109 District of Beijing 1 Court of Beijing Municipality 人民法院 Municipality Changping Changping District People’s 北京市昌平区人 京 0114 110114 District of Beijing 1 Court of Beijing Municipality 民法院 Municipality Yanqing County People’s 延庆县人民法院 京 0229 110229 Yanqing County 1 Court No. 2 Intermediate People's 北京市第二中级 京 02 2 Court of Beijing Municipality 人民法院 Dongcheng Dongcheng District People’s 北京市东城区人 京 0101 110101 District of Beijing 1 Court of Beijing Municipality 民法院 Municipality Xicheng District Xicheng District People’s 北京市西城区人 京 0102 110102 of Beijing 1 Court of Beijing Municipality 民法院 Municipality Fengtai District of Fengtai District People’s 北京市丰台区人 京 0106 110106 Beijing 1 Court of Beijing Municipality 民法院 Municipality 1 Fangshan District Fangshan District People’s 北京市房山区人 京 0111 110111 of Beijing 1 Court of Beijing Municipality 民法院 Municipality Daxing District of Daxing District People’s 北京市大兴区人 京 0115