Cissy Fitzgerald

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Herbert Brenon Ç”Μå½± ĸ²È¡Œ (Ť§Å…¨)

Herbert Brenon 电影 串行 (大全) Quinneys https://zh.listvote.com/lists/film/movies/quinneys-7272298/actors The Clemenceau https://zh.listvote.com/lists/film/movies/the-clemenceau-case-3520302/actors Case Yellow Sands https://zh.listvote.com/lists/film/movies/yellow-sands-8051822/actors The Heart of Maryland https://zh.listvote.com/lists/film/movies/the-heart-of-maryland-3635189/actors The Woman With Four https://zh.listvote.com/lists/film/movies/the-woman-with-four-faces-17478899/actors Faces Empty Pockets https://zh.listvote.com/lists/film/movies/empty-pockets-62333808/actors Honours Easy https://zh.listvote.com/lists/film/movies/honours-easy-12124839/actors Wine, Women and https://zh.listvote.com/lists/film/movies/wine%2C-women-and-song-56291174/actors Song The Custard Cup https://zh.listvote.com/lists/film/movies/the-custard-cup-62595387/actors Moonshine Valley https://zh.listvote.com/lists/film/movies/moonshine-valley-6907976/actors The Eternal Sin https://zh.listvote.com/lists/film/movies/the-eternal-sin-21869328/actors Life's Shop Window https://zh.listvote.com/lists/film/movies/life%27s-shop-window-3832153/actors Laugh, Clown https://zh.listvote.com/lists/film/movies/laugh%2C-clown-1057743/actors God Gave Me Twenty https://zh.listvote.com/lists/film/movies/god-gave-me-twenty-cents-15123200/actors Cents The New Magdalen https://zh.listvote.com/lists/film/movies/the-new-magdalen-15865904/actors The Passion Flower https://zh.listvote.com/lists/film/movies/the-passion-flower-16254009/actors Sin https://zh.listvote.com/lists/film/movies/sin-16908426/actors -

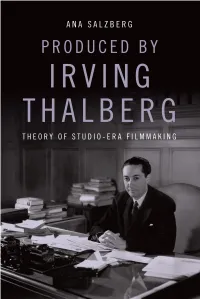

9781474451062 - Chapter 1.Pdf

Produced by Irving Thalberg 66311_Salzberg.indd311_Salzberg.indd i 221/04/201/04/20 66:34:34 PPMM 66311_Salzberg.indd311_Salzberg.indd iiii 221/04/201/04/20 66:34:34 PPMM Produced by Irving Thalberg Theory of Studio-Era Filmmaking Ana Salzberg 66311_Salzberg.indd311_Salzberg.indd iiiiii 221/04/201/04/20 66:34:34 PPMM Edinburgh University Press is one of the leading university presses in the UK. We publish academic books and journals in our selected subject areas across the humanities and social sciences, combining cutting-edge scholarship with high editorial and production values to produce academic works of lasting importance. For more information visit our website: edinburghuniversitypress.com © Ana Salzberg, 2020 Edinburgh University Press Ltd The Tun – Holyrood Road 12(2f) Jackson’s Entry Edinburgh EH8 8PJ Typeset in 11/13 Monotype Ehrhardt by IDSUK (DataConnection) Ltd, and printed and bound in Great Britain A CIP record for this book is available from the British Library ISBN 978 1 4744 5104 8 (hardback) ISBN 978 1 4744 5106 2 (webready PDF) ISBN 978 1 4744 5107 9 (epub) The right of Ana Salzberg to be identified as the author of this work has been asserted in accordance with the Copyright, Designs and Patents Act 1988, and the Copyright and Related Rights Regulations 2003 (SI No. 2498). 66311_Salzberg.indd311_Salzberg.indd iivv 221/04/201/04/20 66:34:34 PPMM Contents Acknowledgments vi 1 Opening Credits 1 2 Oblique Casting and Early MGM 25 3 One Great Scene: Thalberg’s Silent Spectacles 48 4 Entertainment Value and Sound Cinema -

Bibliography Filmography

Blanche Sewell Lived: October 27, 1898 - February 2, 1949 Worked as: editor, film cutter Worked In: United States by Kristen Hatch Blanche Sewell entered the ranks of negative cutters shortly after graduating from Inglewood High School in 1918. She assisted cutter Viola Lawrence on Man, Woman, Marriage (1921) and became a cutter in her own right at MGM in the early 1920s. She remained an editor there until her death in 1949. See also: Hettie Grey Baker, Anne Bauchens, Margaret Booth, Winifred Dunn, Katherine Hilliker, Viola Lawrence, Jane Loring, Irene Morra, Rose Smith Bibliography The bibliography for this essay is included in the “Cutting Women: Margaret Booth and Hollywood’s Pioneering Female Film Editors” overview essay. Filmography A. Archival Filmography: Extant Film Titles: 1. Blanche Sewell as Editor After Midnight. Dir. Monta Bell, sc.: Lorna Moon, ed.: Blanche Sewell (Metro-Goldwyn-Mayer Corp. US 1927) cas.: Norma Shearer, Gwen Lee, si., b&w. Archive: Cinémathèque Française [FRC]. Man, Woman, and Sin. Dir. Monta Bell, sc.: Alice D. G. Miller, Monta Bell, ed.: Blanche Sewell (Metro-Goldwyn-Mayer Corp. US 1927) cas.: John Gilbert, Jeanne Eagels, Gladys Brockwell, si., b&w. Archive: George Eastman Museum [USR]. Tell It to the Marines. Dir.: George Hill, sc.: E. Richard Schayer, ed.: Blanche Sewell (Metro- Goldwyn-Mayer Corp. US 1927) cas.: Lon Chaney, William Haines, si, b&w, 35mm. Archive: George Eastman Museum [USR], UCLA Film and Television Archive [USL]. The Cossacks. Dir.: George Hill, adp.: Frances Marion, ed.: Blanche Sewell (Metro-Goldwyn- Mayer Corp. US 1928) cas.: John Gilbert, Renée Adorée, si, b&w. -

Film Preservation Program Are "Cimarron,"

"7 NO. 5 The Museum of Modern Art FOR RELEASE JANUARY 14 11 West 53 Street, New York, N.Y. 10019 Tel. 955-6100 Cable: Modernart EARLY FILMS TO BE REVIVED AT MUSEUM "The Virginian," Cecil B. DeMllle's 1914 classic, from the novel by Owen Wlster, with Dustin Famun who played in the stage version, will be shown as part of a series of eleven early films to be presented from January 14 through January 25, at The Museum of Modern Art. The Jesse Lasky production of "The Virginian" will be introduced by James Card, Curator of the George Eastman House Motion Picture Study Collection in Rochester, which is providing the films on the Museum program. At the eight o'clock, January 14 performance, Mr. Card will introduce the film and address himself to the controversy over the direction of "The Virginian," one of the early silent feature films. The fact that Cecil B. DeMille directed has been in dispute over the years. On the same program with "The Virginian," another vintage film will be shown. Tod Browning's "The Unknown" starring Lon Chaney. Made in 1927, it was an original story by the director, called "Alonzo, the Armless." According to The New York Times Film Reviews, a recently published compilation of the paper's film criticism, "the role ought to have satisfied Mr. Chaney's penchant for freakish characterizations for here he not only has to go about for hours with his arms strapped to his body, but when he rests behind bolted doors, one perceives that he has on his left hand a double thumb." Joan Crawford plays the female lead in the film, about which Roy Edwards writes in Sight and Sound, the characters and special effects add up to a "thorough display of grotesqueries." Other notable films that are part of this film preservation program are "Cimarron," starring Richard Dix and made in 1931 from Edna Ferber's popular novel; "Dr. -

The Horror Film Series

Ihe Museum of Modern Art No. 11 jest 53 Street, New York, N.Y. 10019 Circle 5-8900 Cable: Modernart Saturday, February 6, I965 FOR IMMEDIATE RELEASE The Museum of Modern Art Film Library will present THE HORROR FILM, a series of 20 films, from February 7 through April, 18. Selected by Arthur L. Mayer, the series is planned as a representative sampling, not a comprehensive survey, of the horror genre. The pictures range from the early German fantasies and legends, THE CABINET OF DR. CALIGARI (I9I9), NOSFERATU (1922), to the recent Roger Corman-Vincent Price British series of adaptations of Edgar Allan Poe, represented here by THE MASQUE OF THE RED DEATH (I96IO. Milestones of American horror films, the Universal series in the 1950s, include THE PHANTOM OF THE OPERA (1925), FRANKENSTEIN (1951), his BRIDE (l$55), his SON (1929), and THE MUMMY (1953). The resurgence of the horror film in the 1940s, as seen in a series produced by Val Lewton at RR0, is represented by THE CAT PEOPLE (19^), THE CURSE OF THE CAT PEOPLE (19^4), I WALKED WITH A ZOMBIE (19*£), and THE BODY SNAT0HER (19^5). Richard Griffith, Director of the Film Library, and Mr. Mayer, in their book, The Movies, state that "In true horror films, the archcriminal becomes the archfiend the first and greatest of whom was undoubtedly Lon Chaney. ...The year Lon Chaney died [1951], his director, Tod Browning,filmed DRACULA and therewith launched the full vogue of horror films. What made DRACULA a turning-point was that it did not attempt to explain away its tale of vampirism and supernatural horrors. -

The Survival of American Silent Feature Films: 1912–1929 by David Pierce September 2013

The Survival of American Silent Feature Films: 1912–1929 by David Pierce September 2013 COUNCIL ON LIBRARY AND INFORMATION RESOURCES AND THE LIBRARY OF CONGRESS The Survival of American Silent Feature Films: 1912–1929 by David Pierce September 2013 Mr. Pierce has also created a da tabase of location information on the archival film holdings identified in the course of his research. See www.loc.gov/film. Commissioned for and sponsored by the National Film Preservation Board Council on Library and Information Resources and The Library of Congress Washington, D.C. The National Film Preservation Board The National Film Preservation Board was established at the Library of Congress by the National Film Preservation Act of 1988, and most recently reauthorized by the U.S. Congress in 2008. Among the provisions of the law is a mandate to “undertake studies and investigations of film preservation activities as needed, including the efficacy of new technologies, and recommend solutions to- im prove these practices.” More information about the National Film Preservation Board can be found at http://www.loc.gov/film/. ISBN 978-1-932326-39-0 CLIR Publication No. 158 Copublished by: Council on Library and Information Resources The Library of Congress 1707 L Street NW, Suite 650 and 101 Independence Avenue, SE Washington, DC 20036 Washington, DC 20540 Web site at http://www.clir.org Web site at http://www.loc.gov Additional copies are available for $30 each. Orders may be placed through CLIR’s Web site. This publication is also available online at no charge at http://www.clir.org/pubs/reports/pub158. -

Mary Murillo

Mary Murillo Also Known As: Mary O’Connor, Mary Velle Lived: January 22, 1888 - February 4, 1944 Worked as: adapter, film company managing director, scenario writer, screenwriter, theatre actress Worked In: France, United Kingdom: England, United States by Christina Petersen In March 1918, Moving Picture World heralded British screenwriter Mary Murillo as a “remarkable example” of “the meteoric flights to fame and fortune which have marked the careers of many present day leaders in the motion picture profession” (1525). This was more than just promotional hyperbole, since, in just four years, Murillo had penned over thirty features, including a highly successful adaptation of East Lynne (1916) starring Theda Bara and the original story for Cheating the Public (1918), “which proved a sensation” at its New York debut according to Moving Picture World (1525). Murillo wrote or adapted over fifty films from 1913 to 1934 in the United States, England, and France, including slapstick comedies, melodramas, fairy tale adaptations, and vehicles for female stars such as Bara, Ethel Barrymore, Clara Kimball Young, Olga Petrova, and Norma Talmadge. As a scenarist, her range included several films focused on contemporary issues—gender equality, women’s suffrage, economic progressivism, and labor reform—while others, such as the child-oriented adaptation of Jack and the Beanstalk (1917), seem to have been meant to appeal as pure escapism. In the latter half of her career, Murillo left the United States for England where she joined several ventures, but never equaled her American output. Born in January 1888 and educated at the Sacred Heart Convent in Roehampton, England, Murillo immigrated to the United States in 1908 at the age of nineteen (“Mary Murillo, Script Writer” 1525; McKernan 2015, 80). -

The Silent Film Project

The Silent Film Project Films that have completed scanning – Significant titles in bold: May 1, 2018 TITLE YEAR STUDIO DIRECTOR STAR 1. [1934 Walt Disney Promo] 1934 Disney 2. 13 Washington Square 1928 Universal Melville W. Brown Alice Joyce 3. Adventures of Bill and [1921] Pathegram Robert N. Bradbury Bob Steele Bob, The (Skunk, The) 4. African Dreams [1922] 5. After the Storm (Poetic [1935] William Pizor Edgar Guest, Gems) Al Shayne 6. Agent (AKA The Yellow 1922 Vitagraph Larry Semon Larry Semon Fear), The 7. Aladdin And The 1917 Fox Film C. M. Franklin Francis Wonderful Lamp Carpenter 8. Alexandria 1921 Burton Holmes Burton Holmes 9. An Evening With Edgar A. [1938] Jam Handy Louis Marlowe Edgar A. Guest Guest 10. Animals of the Cat Tribe 1932 Eastman Teaching 11. Arizona Cyclone, The 1934 Imperial Prod. Robert E. Tansey Wally Wales 12. Aryan, The 1916 Triangle William S. Hart William S. Hart 13. At First Sight 1924 Hal Roach J A. Howe Charley Chase 14. Auntie's Portrait 1914 Vitagraph George D. Baker Ethel Lee 15. Autumn (nature film) 1922 16. Babies Prohibited 1913 Thanhouser Lila Chester 17. Barbed Wire 1927 Paramount Rowland V. Lee Pola Negri 18. Barnyard Cavalier 1922 Christie Bobby Vernon 19. Barnyard Wedding [1920] Hal Roach 20. Battle of the Century 1927 Hal Roach Clyde Bruckman Oliver Hardy, Stan Laurel 21. A Beast at Bay 1912 Biograph D.W. Griffith Mary Pickford 22. Bebe Daniels & Ben Lyon 1931- Bebe Daniels, home movies 1935 Ben Lyon 23. Bell Boy 13 1923 Thomas Ince William Seiter Douglas Maclean 24. -

Hooray for Hollywood!

Hooray for Hollywood! The Silent Screen & Early “Talkies” Created for free use in the public domain American Philatelic Society ©2011 • www.stamps.org Financial support for the development of these album pages provided by Mystic Stamp Company America’s Leading Stamp Dealer and proud of its support of the American Philatelic Society www.MysticStamp.com, 800-433-7811 PartHooray I: The Silent forScreen andHollywood! Early “Talkies” How It All Began — Movie Technology & Innovation Eadweard Muybridge (1830–1904) Pioneers of Communication • Scott 3061; see also Scott 231 • Landing of Columbus from the Columbian Exposition issue A pioneer in motion studies, Muybridge exhibited moving picture sequences of animals and athletes taken with his “Zoopraxiscope” to a paying audience in the Zoopraxographical Hall at the 1893 Columbian Exposition. Although these brief (a few seconds each) moving picture views titled “The Science of Animal Locomotion” did not generate the profit Muybridge expected, the Hall can be considered the first “movie theater.” Thomas Alva Edison William Dickson Motion Pictures, (1847–1947) (1860–1935) 50th Anniversary Thomas A. Edison Pioneers of Communication Scott 926 Birth Centenary • Scott 945 Scott 3064 The first motion picture to be copyrighted Edison wrote in 1888, “I am experimenting Hired as Thomas Edison’s assistant in in the United States was Edison upon an instrument which does for the 1883, Dickson was the primary developer Kinetoscopic Record of a Sneeze (also eye what the phonograph does for the of the Kintograph camera and Kinetoscope known as Fred Ott’s Sneeze). Made January ear.” In April 1894 the first Kinetoscope viewer. The first prototype, using flexible 9, 1894, the 5-second, 48-frame film shows Parlour opened in New York City with film, was demonstrated at the lab to Fred Ott (one of Edison’s assistants) taking short features such as The Execution of visitors from the National Federation of a pinch of snuff and sneezing. -

Meeting of 23Rd Feb 2013

Jitterbugs Tent meeting February 23rd 2013 I began to get a little worried during the afternoon of the 23rd Feb. Snow was falling and sticking to the ground and I wondered about cancelling. After a few hours, it became apparent that we might have a chance after all and so the trek to RTE was made. We had two apologies from Stephen and Tom, the two stalwarts who rarely miss Tent meetings. As we set up the room, a few members arrived and it looked like we were in for a cosy meeting with Stan and Ollie. Young Harry was keen to show me his Asterix the Gaul books with a number of references to Stan and Ollie and I took some photos of the pages, as I had not seen them before. As we began our first film, “The Music Box”, the door opened and a few more bodies filtered in. A few minutes later and a few more joined us... The room was now a respectable 25ish... The Music Box went down very well and all in attendance were warned to watch carefully as a Jitterbugs quiz was on the cards that night. With the final credits playing, the quiz began and the questions were focused on those with eagle eyes who might have seen something that others did not. So how many times did they do the hat switch routine in total? “Going Bye Bye”, was next to adorn the screen and Walter Long’s performance had us all in stitches... Ollie asking how they could help with Stan offering to “get you a sandwich”, had certain members in fits of laughter and it spread to the rest of the room. -

Herbert Brenon Филм ÑÐ ¿Ð¸ÑÑ ŠÐº (ФилмографиÑ)

Herbert Brenon Филм ÑÐ ¿Ð¸ÑÑ ŠÐº (ФилмографиÑ) Quinneys https://bg.listvote.com/lists/film/movies/quinneys-7272298/actors The Clemenceau Case https://bg.listvote.com/lists/film/movies/the-clemenceau-case-3520302/actors Yellow Sands https://bg.listvote.com/lists/film/movies/yellow-sands-8051822/actors The Heart of Maryland https://bg.listvote.com/lists/film/movies/the-heart-of-maryland-3635189/actors The Woman With Four Faces https://bg.listvote.com/lists/film/movies/the-woman-with-four-faces-17478899/actors Empty Pockets https://bg.listvote.com/lists/film/movies/empty-pockets-62333808/actors Honours Easy https://bg.listvote.com/lists/film/movies/honours-easy-12124839/actors Wine, Women and Song https://bg.listvote.com/lists/film/movies/wine%2C-women-and-song-56291174/actors The Custard Cup https://bg.listvote.com/lists/film/movies/the-custard-cup-62595387/actors Moonshine Valley https://bg.listvote.com/lists/film/movies/moonshine-valley-6907976/actors The Eternal Sin https://bg.listvote.com/lists/film/movies/the-eternal-sin-21869328/actors Life's Shop Window https://bg.listvote.com/lists/film/movies/life%27s-shop-window-3832153/actors Laugh, Clown https://bg.listvote.com/lists/film/movies/laugh%2C-clown-1057743/actors Sorrell and Son https://bg.listvote.com/lists/film/movies/sorrell-and-son-1058426/actors God Gave Me Twenty Cents https://bg.listvote.com/lists/film/movies/god-gave-me-twenty-cents-15123200/actors Peter Pan https://bg.listvote.com/lists/film/movies/peter-pan-1537132/actors The Case of Sergeant Grischa https://bg.listvote.com/lists/film/movies/the-case-of-sergeant-grischa-1548848/actors -

Best Picture of the Yeari Best. Rice of the Ear

SUMMER 1984 SUP~LEMENT I WORLD'S GREATEST SELECTION OF THINGS TO SHOW Best picture of the yeari Best. rice of the ear. TERMS OF ENDEARMENT (1983) SHIRLEY MacLAINE, DEBRA WINGER Story of a mother and daughter and their evolving relationship. Winner of 5 Academy Awards! 30B-837650-Beta 30H-837650-VHS .............. $39.95 JUNE CATALOG SPECIAL! Buy any 3 videocassette non-sale titles on the same order with "Terms" and pay ONLY $30 for "Terms". Limit 1 per family. OFFER EXPIRES JUNE 30, 1984. Blackhawk&;, SUMMER 1984 Vol. 374 © 1984 Blackhawk Films, Inc., One Old Eagle Brewery, Davenport, Iowa 52802 Regular Prices good thru June 30, 1984 VIDEOCASSETTE Kew ReleMe WORLDS GREATEST SHE Cl ION Of THINGS TO SHOW TUMBLEWEEDS ( 1925) WILLIAMS. HART William S. Hart came to the movies in 1914 from a long line of theatrical ex perience, mostly Shakespearean and while to many he is the strong, silent Western hero of film he is also the peer of John Ford as a major force in shaping and developing this genre we enjoy, the Western. In 1889 in what is to become Oklahoma Territory the Cherokee Strip is just a graz ing area owned by Indians and worked day and night be the itinerant cowboys called 'tumbleweeds'. Alas, it is the end of the old West as the homesteaders are moving in . Hart becomes involved with a homesteader's daughter and her evil brother who has a scheme to jump the line as "sooners". The scenes of the gigantic land rush is one of the most noted action sequences in film history.