Education in Emergencies: a Tool Kit for Starting

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Annual Report 2020 2 Terre Des Hommes – Annual Report 2020

Annual Report 2020 2 terre des hommes – Annual Report 2020 Imprint Content 2 Imprint 2 Content terre des hommes 3 Greetings Help for Children in Need 4 Executive Board Report Head Office 6 terre des hommes’ mandate Ruppenkampstraße 11 a 8 terre des hommes’ Strategic Goals 49084 Osnabrück 9 How a project arises Germany Phone +49 (0) 5 41/71 01-0 10 terre des hommes project countries Telefax +49 (0) 5 41/70 72 33 12 South Africa: Interview with Cynthia Morrison of [email protected] »A Chance to Play South Africa« www.tdh.de 14 Nicaragua: Women fighting male violence and Account of donations police ignorance BIC NOLADE22XXX 16 India: Assistance for waste picker families IBAN DE34 2655 0105 0000 0111 22 18 Thailand: Together against environmental destruction 20 Iraq: Interview with project director Jessica Prentice Editorial Staff 22 Berlin: Guardians for refugee children Wolf-Christian Ramm (editor in charge), 24 The donation year 2020 Tina Böcker-Eden, Michael Heuer, 25 Volkswagen workforce gives humanitarian assistance Athanasios Melissis, Iris Stolz in coronavirus pandemic Editorial Assistant Cornelia Dernbach Balance 2020 27 terre des hommes in figures Photos Front cover, p. 6, 15, 17 (top), 19, 25, 35, 37, 38, 44, 45 (top), 48, 49, 50: terre des hommes; p. 3 (top), 34 Outlook and future challenges 8 (left), 9, 16, 21 (top), 42 (right), 43 (bottom), 46, 47: 36 Results-based approach at terre des hommes C. Kovermann / terre des hommes; p. 3 (bottom), 37 Quality assurance, monitoring, transparency p. 13 (top), p. 43 (right): privat; p. 4, 14: Projektpartner; 40 Risk management p. -

Wo M En C O U

“All peace and security advocates – both individually and as part of organizational work - should read the 2012 civil society monitoring report on Resolution 1325! It guides us to where we should focus our energies and resources to ensure women’s equal participation in all peace processes and at all decision- making levels, thereby achieving sustainable peace.” -Ambassador Anwarul K. Chowdhury, Former Under- Secretary-General and High Representative of the United Nations “The GNWP initiative on civil society monitoring of UNSCR 1325 provides important data and analysis Security Council Resolution 1325: Security Council Resolution WOMEN COUNT WOMEN COUNT on the implementation of the resolution at both the national and local levels. It highlights examples of what has been achieved, and provides a great opportunity to reflect on how these achievements can Security Council Resolution 1325: be further applied nationwide. In this regard my Ministry is excited to be working with GNWP and its members in Sierra Leone on the Localization of UNSCR 1325 and 1820 initiatives!” - Honorable Steve Gaojia, Minister of Social Welfare, Gender & Children’s Affairs, Government of Sierra Leone Civil Society Monitoring Report 2012 “The 2012 Women Count: Security Council Resolution 1325 Civil Society Monitoring Report uses locally acceptable and applicable indicators to assess progress in the implementation of Resolution 1325 at the country and community levels. The findings and recommendations compel us to reflect on what has been achieved thus far and strategize on making the implementation a reality in places that matters. Congratulations to GNWP-ICAN on this outstanding initiative!” - Leymah Gbowee, 2011 Nobel Peace Prize Laureate “The civil society monitoring report on UNSCR 1325 presents concrete data and analysis on Civil Society 2012 Report Monitoring the implementation of the resolution at national level. -

Acercamiento De La Corporacion Pueblo De Los Niños a La

ACERCAMIENTO DE LA CORPORACIÓN PUEBLO DE LOS NIÑOS A LA COOPERACIÓN INTERNACIONAL MANUELA GONZÁLEZ TRUJILLO MATEO RAMOS CUESTA ESCUELA DE INGENIERÍA DE ANTIOQUIA INGENIERÍA ADMINISTRATIVA ENVIGADO 2007 ACERCAMIENTO DE LA CORPORACIÓN PUEBLO DE LOS NIÑOS A LA COOPERACIÓN INTERNACIONAL MANUELA GONZÁLEZ TRUJILLO MATEO RAMOS CUESTA Trabajo de grado para optar al título de INGENIEROS ADMINISTRADORES Luz Patricia Velásquez Aguilar Directora de la Corporación Pueblo de los Niños Tatiana González Asesora Metodológica EIA ESCUELA DE INGENIERÍA DE ANTIOQUIA INGENIERÍA ADMINISTRATIVA ENVIGADO 2007 Nota de aceptación: Envigado, Junio 8 de 2007 Dedicado a los niños, niñas y jóvenes de nuestra ciudad, ya que deseamos ver sus rostros llenos de alegría y esperanza, pues son ellos el futuro de nuestra sociedad. AGRADECIMIENTOS Gracias a nuestras familias por el apoyo permanente que nos han brindado no sólo en la realización de este trabajo sino a lo largo de nuestra formación profesional, y un agradecimiento especial a la Corporación Pueblo de los Niños por permitirnos ser integrantes activos dentro de la institución y por inculcarnos día a día valores sociales con el fin de contribuir en la construcción de una mejor sociedad para los niños, niñas y jóvenes de nuestra ciudad. CONTENIDO pág. INTRODUCCIÓN............................................................................................................. 12 1. PRELIMINARES ................................................................................................... 14 1.1 Planteamiento del problema -

Relocating Artists at Risk in Latin America Cuny, Laurence

www.ssoar.info Relocating Artists at Risk in Latin America Cuny, Laurence Veröffentlichungsversion / Published Version Forschungsbericht / research report Empfohlene Zitierung / Suggested Citation: Cuny, L. (2021). Relocating Artists at Risk in Latin America. (ifa Edition Culture and Foreign Policy). Stuttgart: ifa (Institut für Auslandsbeziehungen). https://doi.org/10.17901/AKBP1.05.2021 Nutzungsbedingungen: Terms of use: Dieser Text wird unter einer CC BY-NC-ND Lizenz This document is made available under a CC BY-NC-ND Licence (Namensnennung-Nicht-kommerziell-Keine Bearbeitung) zur (Attribution-Non Comercial-NoDerivatives). For more Information Verfügung gestellt. Nähere Auskünfte zu den CC-Lizenzen finden see: Sie hier: https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0 https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/deed.de Diese Version ist zitierbar unter / This version is citable under: https://nbn-resolving.org/urn:nbn:de:0168-ssoar-72476-2 ifa Editi on Culture and Foreign Policy Policy Foreign and on Culture Editi ifa ifa Editi on Culture and Foreign Policy a Marti n Roth-Initi ati ve Publicati on • Relocating Artists at Risk in Latin America Risk in Latin at Artists Relocating Relocati ng Arti sts at Risk in Lati n America Relocati ng Arti sts at Risk in Lati n America Laurence Cuny This report maps existi ng support networks for arti sts at risk in Lati n America and conditi ons for regional temporary relocati on initi ati ves. What must protecti on programmes take into account to meet the specifi c needs of arti sts? What is needed to expand existi ng initi ati ves or create new ones? What support do initi ati ves in the arts and cultural sector need to include politi cally persecuted arti sts? And how can we on ati ve Publicati Roth-Initi n a Marti build a bridge for partnerships between art insti tuti - ons and human rights organisati ons? ifa Edition Culture and Foreign Policy – a Martin Roth-Initiative Publication Relocating Artists at Risk in Latin America Laurence Cuny Content Content Forewords ……….…………………………………………………………………………………………….……. -

Estética Y Filosofía Del Cuerpo En El Circo Desde La Perspectiva Del

FACULTAD DE CIENCIAS JURÍDICAS Y SOCIALES DEPARTAMENTO DE CIENCIAS DE LA EDUCACIÓN,LENGUAJES, CULTURA Y ARTES, CIENCIAS HISTÓRICO-JURÍDICAS Y HUMANÍSTICAS Y LENGUAS MODERNAS FILOSOFÍA Y ESTÉTICA DEL CUERPO EN EL CIRCO DESDE LA PERSPECTIVA DEL CONCEPTO DE BIOPODER TESIS DOCTORAL presentada por Jorge Gallego Silva DIRECTOR ProFesor Doctor D. Carlos Roldán López Madrid, Julio de 2015 INFORME DEL DIRECTOR DE LA TESIS. TITULO DE LA TESIS: FILOSOFIA Y ESTETICA DEL CUERPO EN EL CIRCO DESDE LA PERSPECTIVA DEL CONCEPTO DE BIOPODER. La tesis doctoral de D. Jorge Gallego Silva contextualiza adecuadamente el complejo pensamiento de Michel Foucault para desde esta contextualización responder a la vocación fundamental de toda su obra: Ser utilizado como una caja de herramientas. Michel Foucault analizó pormenorizadamente los dispositivos de subjetivación que nos llevaron a ser lo que somos. Con una especial incidencia en los procesos de normalización corporal sobre el conjunto de las poblaciones. La Tesis que aquí se presenta viene a desarrollar la premisa Foucaltiana de la existencia de los llamados espacios heterotópicos, siendo el circo uno de ellos, sin que el pensador francés desarrollará la razón de ello. De una forma coherente y sistematizada, rigurosamente adepta al legado genealógico de Michel Foucault, que es necesario conocer para entender no sólo que se investiga, sino sobre todo como se investiga, la tesis aquí presentada presenta el circo como espacio heterotópico a través de un estudio casuístico de los dispositivos de subjetivación o técnicas del cuidado de sí que los trabajadores circenses aplican sobre sus propios cuerpos. La tesis doctoral que aquí se presenta cumple, a mi juicio, con todos los requisitos de fondo y forma para proceder a su lectura y defensa como el procedimiento otorga. -

Terre Des Hommes – Annual Report 2017

Annual Report 2017 2 terre des hommes – Annual Report 2017 Imprint Contents terre des hommes 3 Greeting Help for Children in Need 4 Report by the Executive Board 6 terre des hommes’ vision Head Office 8 terre des hommes’ programme activities Ruppenkampstraße 11a 49 084 Osnabrück Germany Goals and impacts of our programme activity 10 Participation makes children strong Phone +49 (0) 5 41/71 01-0 13 Creating safe spaces for children Telefax +49 (0) 5 41/70 72 33 16 Children’s right to a healthy environment [email protected] 19 Advocacy for children’s rights www.tdh.de 22 Map of project countries Account of donations BIC NOLADE 22 XXX 28 Quality assurance, monitoring, transparency IBAN DE34 2655 0105 0000 0111 22 30 Risk management 31 The International Federation TDHIF Editorial Staff 32 You change more than you give Wolf-Christian Ramm (editor in charge), 36 The 2017 donation year Tina Böcker-Eden, Michael Heuer, 38 »How far would you go?!« Athanasios Melissis, Iris Stolz 40 terre des hommes spotlights itself Editorial Assistant Cornelia Dernbach Balance 2017 44 terre des hommes in figures Photos Front cover: M. Pelser; p. 3 top, 8, 37: F. Kopp; p. 3 bottom, 50 Outlook and future challenges 14, 19, 27, 33 bottom, 40 top, 52 bottom, 52 m., 53 top: 52 Organisation structure of terre des hommes C. Kovermann / terre des hommes; p. 4: M. Klimek; 54 Organisation chart of terre des hommes p. 7: S. Basu / terre des hommes; p. 11, 21: Kindernothilfe; p. 12: T. Schwab; p. 13: terre des hommes Lausanne; p. -

Mapping of Temporary Shelter Initiatives for Human Rights Defenders in Danger in and Outside the EU Final Report February 2012

Mapping of temporary shelter initiatives for Human Rights Defenders in danger in and outside the EU Final Report February 2012 This page is intentionally blank Mapping of temporary shelter initiatives for Human Rights Defenders in danger in and outside the EU Final Report Mapping of temporary shelter initiatives for Human Rights Defenders in danger in and outside the EU Final Report February 2012 A report submitted by GHK Consulting in association with HTSPE February 2012 J40252612 GHK Consulting Ltd 67 Clerkenwell Road London EC1R 5BL T +44 (0) 20 7611 1100 F +44 (0) 20 8368 6960 [email protected] www.ghkint.com i Mapping of temporary shelter initiatives for Human Rights Defenders in danger in and outside the EU Final Report Document control Document Title Mapping of temporary shelter initiatives for Human Rights Defenders in danger in and outside the EU Final Report Job number J40252612 Prepared by Nicolaj Sønderbye Checked by Karin Tang Date February 2012 ii Mapping of temporary shelter initiatives for Human Rights Defenders in danger in and outside the EU Final Report Abbreviations AEDH Agir Ensemble pour les Droits de L’Homme AI Amnesty International AOHR Arab Organisation for Human Rights AWID Association for Women's Rights in Development CAHR Centre for Applied Human Rights (CAHR) at York University CCJ Colombian Commission of Jurists CCS Committee of Concerned Scientists CHRD Chinese Human Rights Defenders CJFE Canadian Journalists for Free Expression CAL Coalition of African Lesbians CARA Council for assisting refugee academics -

Directory of Emergency and Rapid Response Grants

DIRECTORY OF EMERGENCY/RAPID RESPONSE GRANTS 2015 Compiled by IHRFG’s Human Rights Defenders Working Group Table of Contents 1. Agir Ensemble pour les Droits de l’Homme (AEDH) 2. American Jewish World Service (AJWS) 3. Amnesty International (AI) 4. Arab Human Rights Fund (AHRF) 5. Asian Forum for Human Rights and Development (FORUM-ASIA) 6. Astraea Lesbian Foundation for Justice 7. Centre for Applied Human Rights (CAHR), University of York 8. Chinese Human Rights Defenders 9. Coalition for African Lesbians (CAL) 10. Colombian Commission of Jurists (CCJ) (La Comisiona de Juristas) 11. Digital Defenders 12. East and Horn of Africa Human Rights Defenders Project (EHAHRDP) 13. Euro-Mediterranean Foundation of Support to Human Rights Defenders (EMFHRD) 14. Freedom House 15. Frontline Defenders 16. Fund for Global Human Rights 17. Guatemala Human Rights Commission (GHRC) 18. Human Rights First 19. International Cities of Refuge Network 20. International Federation for Human Rights (FIDH) 21. International Media Support (IMS) 22. KinderUSA 23. Komnas Perempuan (Indonesia’s National Commission on Violence against Women) 24. Lifeline Embattled NGO Assistance Fund 25. MADRE 26. Mediterranean Women’s Fund 27. Mobilize Power Fund (Third Wave Fund) 28. National Endowment for Democracy (NED) 29. Protection International (PI) 30. Reporters Without Borders 31. RAITH Foundation 32. Rory Peck Trust 33. Scholar Rescue Fund (SRF) 34. Scholars at Risk Network 35. Somos Defenseros Program (We Are Defenders Program) 36. Southern Africa Human Rights Defenders Trust (SAHRDT) 37. Unidad de Protección a Defensoras y Defensores de Derechos Humanos – Guatemala (UDEFEGUA) 38. Urgent Action Fund for Women’s Human Rights (UAF) 39. -

Reconciliation and Development Program (REDES)

Sida Evaluation 07/37 Reconciliation and Development Program (REDES) Sida – UNDP Partnership for Peace in Colombia 2003–2006 t Elisabeth Scheper Anders Rudqvist María Camila Moreno Department for Latin America Reconciliation and Development Program (REDES) Sida – UNDP Partnership for Peace in Colombia 2003–2006 Elisabeth Scheper Anders Rudqvist María Camila Moreno Sida Evaluation 07/37 Department for Latin America This report is part of Sida Evaluations, a series comprising evaluations of Swedish development assistance. Sida’s other series concerned with evaluations, Sida Studies in Evaluation, concerns methodologically oriented studies commissioned by Sida. Both series are administered by the Department for Evaluation and Internal Audit, an independent department reporting directly to Sida’s Board of Directors. This publication can be downloaded/ordered from: http://www.sida.se/publications Authors: Elisabeth Scheper, Anders Rudqvist, María Camila Moreno. The views and interpretations expressed in this report are the authors’ and do not necessarily refl ect those of the Swedish International Development Cooperation Agency, Sida. Sida Evaluation 07/37 Commissioned by Sida, Department for Latin America Copyright: Sida and the authors Registration No.: 981-586 Date of Final Report: December 2006 Printed by Edita Communication AB, 2007 Art. no. SIDA40234en ISBN 978-91-586-8164-4 ISSN 1401— 0402 SWEDISH INTERNATIONAL DEVELOPMENT COOPERATION AGENCY Address: SE-105 25 Stockholm, Sweden. Offi ce: Valhallavägen 199, Stockholm Telephone: +46 (0)8-698 -

A Hrc Wg.6 30 Col 3 E.Pdf

United Nations A/HRC/WG.6/30/COL/3 General Assembly Distr.: General 12 March 2018 English Original: English/Spanish Human Rights Council Working Group on the Universal Periodic Review Thirtieth session 7–18 May 2018 Summary of Stakeholders’ submissions on Colombia* Report of the Office of the United Nations High Commissioner for Human Rights I. Background 1. The present report was prepared pursuant to Human Rights Council resolutions 5/1 and 16/21, taking into consideration the periodicity of the universal periodic review. It is a summary of 55 stakeholders’ submissions1 to the universal periodic review, presented in a summarized manner owing to word-limit constraints. A separate section is provided for the contribution by the national human rights institution that is accredited in full compliance with the Paris Principles. II. Information provided by the national human rights institution accredited in full compliance with the Paris Principles 2. The Ombudsman’s Office of Colombia noted that the National Development Plan 2010–2014 had explicitly incorporated a gender perspective, including with specific actions; the National Development Plan 2014–2018 was less progressive in that regard, however.2 3. The Office indicated that article 24 of Legislative Act No. 01 of 2017 limited the degree and scope of the responsibility of commanders and other officers in the forces of law and order, in breach of article 28 of the Rome Statute of the International Criminal Court, and mentioned the particular consequences that that limitation would have for the victims of sexual violence.3 4. The Office welcomed the release of the Action Plan on Business and Human Rights in 2015; however, it noted that 23 per cent of social protests or demonstrations related to business activity.4 The Office also welcomed the progress made by the State regarding human rights within the framework of international investment agreements.5 5. -

Icsp-Funded Projects

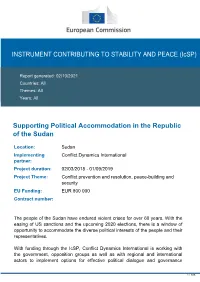

INSTRUMENT CONTRIBUTING TO STABILITY AND PEACE (IcSP) Report generated: 02/10/2021 Countries: All Themes: All Years: All Supporting Political Accommodation in the Republic of the Sudan Location: Sudan Implementing Conflict Dynamics International partner: Project duration: 02/03/2018 - 01/09/2019 Project Theme: Conflict prevention and resolution, peace-building and security EU Funding: EUR 800 000 Contract number: The people of the Sudan have endured violent crises for over 60 years. With the easing of US sanctions and the upcoming 2020 elections, there is a window of opportunity to accommodate the diverse political interests of the people and their representatives. With funding through the IcSP, Conflict Dynamics International is working with the government, opposition groups as well as with regional and international actors to implement options for effective political dialogue and governance 1 / 405 arrangements. Political representatives are given the tools to reach a sufficient degree of consensus, and encouraged to explore inclusive and coherent political processes. This is being achieved through a series of seminars and workshops (with a range of diverse stakeholders). Technical support is provided to the government as well as to main member groups within the opposition, and focus group discussions are being conducted with influential journalists and political actors at a national level. Regional and international actors are being supported in their efforts to prevent and resolve conflict through a number of initiatives. These include organising at least two coordination meetings, the provision of technical support to the African Union High-Level Implementation Panel, and consultations with groups active in the peace process. Through this support, the action is directly contributing to sustainable peace and political stability in Sudan and, indirectly, to stability and development in the Greater East African Region. -

Director Paisanos

AÑO XXV No. 149 Sep-Octubre 2020 Fundador y Director Felipe Cid Domínguez “Publicación periódica para uso exclusivo e interno de la comunidad española de Las ideas justas, por sobre Cuba, en general, y en particular de la gallega y sus descendientes en el mundo”. todo obstáculo y valla, llegan a logro. José Martí. Paisanos: Continuamos con la Pandemia del Covid-19, pero los que tratamos por todos los medios de tener informados a nuestros lectores no detendremos nuestra marcha, claro, las actividades asociativas detenidas como detenido está parte de nuestra bella isla, la mayor de las Antillas. También otros países están afectados con esta horrible pesadilla que ha arrebatado tantas vidas no solo de adultos mayores sino también de jóvenes que podían aportar mucho más a la sociedad civil cubana y mundo en general. La insensatez del ser humano está provocando el caos. Digo caos pues al no haber la movilidad necesaria y acostumbrada entre las personas, las economías bajan y las escaseces serán el Pan nuestro de cada día. Aún los terrícolas no han interiorizado que el Covid-19 MATA. Las indisciplinas sociales, no solo en Cuba sino en todo el globo terráqueo será la responsable de más infectados y más muertes. Si escucháramos las cifras de fallecidos y los salvados con secuelas irreversibles nos asombramos, pero al salir de casa no usamos con responsabilidad el nosobuco que hasta el momento ayuda a no contagiarnos. De una vez por toda debemos tomar conciencia e interiorizar que el remedio es una vacuna contra esta reina sin corona. Muchos países incluyendo el nuestros están tratando de encontrarla, pero hasta el momento del cierre de esta edición aún no ha sido descubierta.