Third Millennium Nrms in Britain

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Code Description Start Date End Date A1 Protestant Episcopal Church

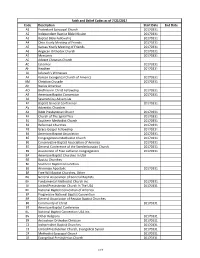

Faith and Belief Codes as of 7/21/2017 Code Description Start Date End Date A1 Protestant Episcopal Church 20170331 A2 Independent Baptist Bible Mission 20170331 A3 Baptist Bible Fellowship 20170331 A4 Ohio Yearly Meeting of Friends 20170331 A5 Kansas Yearly Meeting of Friends 20170331 A6 Anglican Orthodox Church 20170331 A7 Messianic 20170331 AC Advent Christian Church AD Eckankar 20170331 AH Heathen 20170331 AJ Jehovah’s Witnesses AK Korean Evangelical Church of America 20170331 AM Christian Crusade 20170331 AN Native American AO Brethren In Christ Fellowship 20170331 AR American Baptist Convention 20170331 AS Seventh Day Adventists AT Baptist General Conference 20170331 AV Adventist Churches AX Bible Presbyterian Church 20170331 AY Church of The Spiral Tree 20170331 B1 Southern Methodist Church 20170331 B2 Reformed Churches 20170331 B3 Grace Gospel Fellowship 20170331 B4 American Baptist Association 20170331 B5 Congregational Methodist Church 20170331 B6 Conservative Baptist Association of America 20170331 B7 General Conference of the Swedenborgian Church 20170331 B9 Association of Free Lutheran Congregations 20170331 BA American Baptist Churches In USA BB Baptist Churches BC Southern Baptist Convention BE Armenian Apostolic 20170331 BF Free Will Baptist Churches, Other BG General Association of General Baptists BH Fundamental Methodist Church Inc. 20170331 BI United Presbyterian Church In The USA 20170331 BN National Baptist Convention of America BP Progressive National Baptist Convention BR General Association of Regular Baptist -

The Brokenbody Ti-Mbrokenbody

r f THE BROKENBODY TI-MBROKENBODY an examination, PrePard especially for laymen, of what has happened in &e Episcopal church (PECUSA) in recent years, and what is being done by those determined to keep the Faith. This is not to encourage any exodus from PECUSA but to make possible an intelligent choice by those who do. ...by a Retired Priest INDEX ByWayoflntroduction..... 3 TheGreatEcumenicalGamePlan ..--..- 4 ABackgroundof History ...... 6 TheApostolicSuccession; isitnecessary? .... ... 11 WhatisanAnglo-Catholic?. ....I2 WhatisanEvangelical?.... ....I2 JustWhatDoesOrthodoxMean? .......13 EpiscopiVagantes '..... It ListofQuestions... ....17 ReformedEpiscopalChurch .... .......18 AnglicanOrthodoxChurch '....21 AmericanEpiscopalChurch .....24 AnglicanEpiscopalChurch ......27 AnglicanCatholicChurch '..'..30 Page 3 By Way of Introduction..... This booklet is written especially for the laymen since he rarely has opportunity to read church periodicals for an understanding of what has happened in the Episcopal Church in the past l5 years. To simplify matters we'll hereafter use several acronyms, the first of which is PECUSA (Protestant Episcopal Church in U.S.A.) Most of us are aware that the "troubles" (as the Irish call their revolutionary problems) came to a head at the 1976 Minneapolis General Convention, although there had been departures from PECUSA as far back as 1873. The purpose is to tell you about it without any theological gobbledegook and with as few judgmental comments as possible. The original intent of this project was to describe the origins of the seven better-known separated churches; it was soon discovered that there were neady fifty, most of which are small entities located in the southern states. The search for information showed a lot of cross- patching and cross-referencing, so in order to avoid stumbling all over ourselves we decided to confine this report to the seven. -

53. Presbyteral Transfers and Reinstatements

53. Presbyteral Transfers and Reinstatements 1. Recommendations of the Ministerial Candidates’ Selection Committee acting as a Transfer Committee The report of the Appeals Committee on applicants who have appealed against the recommendations of the committee under Standing Order 730(10) [see also SO 730(14)] Two cases Report on cases where there have been medical objections No case Applicants for transfer recommended by a 75% majority or more in the Ministerial Candidates’ Selection Committee to be transferred to the jurisdiction of this Conference under SO 730 Barry James Allen (the Methodist Church of Southern Africa) Luiz Fernando Cardoso (the Methodist Church, Brazil) Lynita Conradie (The Methodist Church of Southern Africa) Gyula Ferenc Fiák (Church of the Nazarene) Alan Geoffrey Palmer (Evangelical Fellowship of Congregational Churches) Marian Alexandra Taylor (The Church of England) Nana Banyin Thomford (Anglican Orthodox Church) Jongikaya Zihle (The Methodist Church of Southern Africa) Applicants for transfer as a probationer recommended by a 75% majority or more in the Ministerial Candidates’ Selection Committee to be transferred to the jurisdiction of this Conference under SO 730 Shalome MacNeill Cooper (Probationer (United Church of Canada) Applicants for transfer recommended by a 75% majority or more in the Ministerial Candidates’ Selection Committee to proceed to initial training and probation Sang Wook Han (Jesus Korea Sungkyul Church) Applicants for transfer recommended by a 75% majority or more in the Ministerial Candidates’ -

FACT 2005 Congregational Profile

2005 NATIONAL SURVEY OF CONGREGATIONS CONGREGATIONAL PROFILE Your congregation has been randomly selected to participate in a national study of religion in America. To have a complete picture, we need to hear from every congregation selected. The survey can be completed by the leader of the congregation, a paid staff member, or a lay leader. Some questions may not apply to your religious tradition. If so, just skip the question and go to the next one. Please note that the survey may also be completed on the Internet at http://fact.hartsem.edu/survey Thank you for your willingness to be a part of this important national study. Your Respondent Key In the boxes provided, please write the six-character respondent key printed above your address on your postcard or on your original questionnaire cover. This code will ensure we remove you from our follow-up reminder list. Thank you! A. Your Congregation’s Worship 1. How often does your congregation hold worship services? 1 One day each week 2 More than one day each week 3 Several times a month, but not every week 4 Several times a year 5 Weekly during part of the year (such as summer or ski season) 6 Some other pattern (please describe): 2. How many worship services does your congregation usually hold each weekend? Do not include special services, weddings, or funerals; please write just one number: services 3. How well do the following describe your congregation’s largest weekend worship service? NOT AT QUITE VERY CHECK ONE OPTION ON EACH LINE ALL SLIGHTLY SOMEWHAT WELL WELL A. -

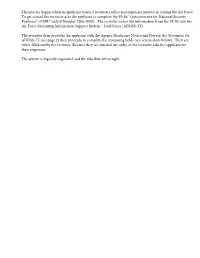

The Process Begins When an Applicant Enters a Recruiters Office and Expresses Interest in Joining the Air Force

The process begins when an applicant enters a recruiters office and expresses interest in joining the Air Force. To get started the recruiter asks the applicant to complete the SF-86 "Questionnaire for National Security Positions" (OMB Control Number 3206-0005). The recruiter enters the information from the SF-86 into the Air Force Recruiting Information Support System - Total Force (AFRISS-TF). The recruiter then provides the applicant with the Agency Disclosure Notice and Privacy Act Statement for AFRISS-TF (see page 2) then proceeds to complete the remaining fields (see screen shots below). They are either filled out by the recruiter (because they are internal use only) or the recruiter asks the applicant for their responses. The system is logically organized and the tabs flow left to right. OMB CONTROL NUMBER: 0701-0150 OMB EXPIRATION DATE: MM/DD/YYYY AGENCY DISCLOSURE NOTICE The public reporting burden for this collection of information, 0701-0150, is estimated to average 180 minutes per response, including the time for reviewing instructions, searching existing data sources, gathering and maintaining the data needed, and completing and reviewing the collection of information. Send comments regarding the burden estimate or burden reduction suggestions to the Department of Defense, Washington Headquarters Services, at whs.mc- [email protected]. Respondents should be aware that notwithstanding any other provision of law, no person shall be subject to any penalty for failing to comply with a collection of information if it does not display a currently valid OMB control number. PRIVACY ACT STATEMENT: The following information is provided to comply with the Privacy Act (PL93-579). -

Protestant Episcopal Church the Episcopal Church

JOURNAL OF THE GENERAL CONVENTION OF THE Protestant Episcopal Church IN THE UNITED STATES OF AMERICA OTHERWISE KNOWN AS The Episcopal Church Held in Seattle, Washington, From September Seventeenth to Twenty-Seventh, inclusive, in the Year of Our Lord 1967 WITH APPENDICES AND SUPPLEMENTS PRINTED FOR THE CONVENTION 1967 ECUMENICAL RELATIONS Appendix 9.1 APPENDIX 9. REPORT OF THE JOINT COMMISSION ON ECUMENICAL RELATIONS CONTENTS Introduction 9.3 Members of the Joint Commission 9.4 Structureof the Joint Commission 9.6 The Report 9.7 1. Relations with the Eastern Churches 9.7 2. Relations with the Roman Catholic Church 9.12 3. Consultation on Church Union 9.15 4. Pentecostal and ConservativeEvangelical Churches 9.21 5. World and National Councils of Churches 9.22 6. Jewish-ChristianDialogue 9.23 7. TheologicalConcerns 9.23 8. The Wider Episcopal Fellowship 9.24 9. The West Indies 9.27 10. Ecumenical Relations of the ExecutiveCouncil 9.27 11. Inter-Anglican Relations 9.28 Summary 9.30 Resolutions 9.31 Annexes 9.36 A. Interim Guide-Lines for Anglican-Orthodox Relationships 9.36 B. Resolutionof the BelgradeConference 9.38 C. Interim Guide-Lines for Relations with the Roman Catholic Church 9.42 D. Principles of Church Union 9.45 E. Episcopal Delegatesto EcumenicalGatherings 9.46 F. Statement on Communion Discipline 9.54· G. Financial Report 9.55 9.2 Appendix ECUMENICAL RELATIONS In jIltmoriam Whereas, Ralph W. Black served as a faithful member of the Joint Commission on Ecumenical Relations from 1961 until his death on August 22, 1966; and Whereas, He is mourned, not only by his family and by the Missionary District of North Dakota, but by his friends and fellow-workers throughout the Church; therefore, be it . -

The Certain Trumpet Fall 2011

The Certain Trumpet (Fall 2011) 1 The Certain Trumpet Fall 2011 by Wallace H. Spaulding THE ATTACK ON SOUTH CAROLINA IS AN ATTACK ON ALL MORAL EPISCOPALIANS UNIDENTIFIED DISSIDENTS within the Episcopal Diocese of South Carolina submitted “evidence” to the Disciplinary Board of Bishops in September 2011 which they believe shows that their bishop, the Rt. Rev. Mark J. Lawrence, has “abandoned” the Episcopal Church (TEC). Lawrence is cited most notably for presiding over his diocese’s 2009 convention, which voted to “begin withdrawing from all bodies of the Episcopal Church that have assented to actions contrary to Holy Scripture, the doctrine and worship of Christ as this Church has received them, the resolutions of the Lambeth Conference which have expressed the mind of the Communion, the Book of Common Prayer, and our Constitution and Canons, until such bodies show willingness to repent of such actions.” (The primary issue, of course, is the homosexual agenda and, secondarily, abortion.) The charge does have a certain logic, since, if the General Convention, TEC’s highest legislative body, approves the “gay marriage” proposal to be presented to it in 2012 (as is certainly anticipated), South Carolina might be expected to withdraw from that body. But the implication of this action is horrendous: Any discipline of Bishop Lawrence over the issue would indicate that TEC authorities maintain that one cannot be a TEC member in good standing unless he/she endorses, or at least tolerates, sodomy and abortion. And who has the last word in defining the requirements of church membership, other than these very authorities? What of the other Episcopal dioceses that approve of South Carolina’s stand on these moral issues? They are, first of all, the 5 among the 2004-2008 Anglican Communion Network dioceses that, along with South Carolina, did not go into the new Anglican Church in North America (ACNA) in 2009: Albany, Central Florida, Dallas, Rio Grande, and Springfield (IL). -

The Development of Youth Ministry As a Professional Career and the Distinctives of Liberty University Youth Ministry Training in Preparing Students for Youth Work

LIBERTY BAPTIST THEOLOGICAL SEMINARY THE DEVELOPMENT OF YOUTH MINISTRY AS A PROFESSIONAL CAREER AND THE DISTINCTIVES OF LIBERTY UNIVERSITY YOUTH MINISTRY TRAINING IN PREPARING STUDENTS FOR YOUTH WORK A Thesis Project Submitted to Liberty Baptist Theological Seminary in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree DOCTOR OF MINISTRY By David E. Adams Forest, Virginia March 15, 1993 Copyright 1993 David E. Adams All Rights Reserved LIBERTY BAPTIST THEOLOGICAL SEMINARY THESIS APPROVAL SHEET A Grade Mentor Reader ABSTRACT THE DEVELOPMENT OF YOUTH MINISTRY AS A PROFESSIONAL CAREER AND THE DISTINCTIVES OF LIBERTY UNIVERSITY YOUTH MINISTRY TRAINING IN PREPARING STUDENTS FOR YOUTH WORK David E. Adams Liberty Baptist Theological Seminary, 1993 Mentor: Dr.Ronald Hawkins The purpose of this thesis project is to demonstrate that youth ministry is a viable discipline warranting appropriate career consideration for those called into ministry. This project documents the development of the distinctiveness of the Liberty University Youth Major in preparing men and women for youth work. The first part documents the historical roots of youth ministry. Special attention is given to significant events, important personalities and founding youth organizations. Part two reveals how youth ministry became a profession. Ecclesiastical and sociological influences are considered. Section three demonstrates how Liberty University is responding to the need to prepare competent professionals. Total Number of Words: 100 iv TABLE OF CONTENTS ABSTRACT iv LIST OF TABLES ix INTRODUCTION AND OVERVIEW 10 PART ONE THE HISTORICAL ROOTS OF YOUTH MINISTRY PROFESSION I. THE HISTORICAL DEVELOPMENT OF YOUTH MINISTRY 17 Pre-1800 / s Youth Work 17 Revival at Amherst I Dartmouth l Princeton 17 1700/s - Discovering the roots of modern. -

Toward a Classification System of Religious Groups in the Americas by Major Traditions and Family Types

LATIN AMERICAN SOCIO-RELIGIOUS STUDIES PROGRAM (PROLADES) TOWARD A CLASSIFICATION SYSTEM OF RELIGIOUS GROUPS IN THE AMERICAS BY MAJOR TRADITIONS AND FAMILY TYPES Clifton L. Holland, Editor First Edition: 30 October 1993 Last Modified on 20 April 2010 PROLADES Apartado 1524-2050, San Pedro, Costa Rica Telephone: (506) 283-8300; Fax (506) 234-7682 E-Mail: [email protected] Internet: http://www.prolades.com © Clifton L. Holland 2006, 2007, 2008, 2009, 2010 PROLADES Apartado 1524-2050 San José, Costa Rica All Rights Reserved 2 CONTENTS 1. Document #1: Toward a Classification System of Religious Groups in the Americas by Major Traditions and Family Types 7 2. Document #2: An Annotated Outline of the Classification System of Religious Groups by Major Traditions, Families and Sub-Families with Special Reference to the Americas 15 PART A: THE OLDER LITURGICAL CHRISTIAN TRADITIONS 15 A1.0 EASTERN LITURGICAL TRADITIONS 15 A1.10 EASTERN OTHODOX TRADITION 15 A1.11 Patriarchates 16 A1.12 Autocephalous Orthodox Churches 16 A1.13 Other Orthodox Churches in the Americas 17 A1.14 Schismatic Groups of Eastern Orthodox Origins 18 A1.20 NON-CALCEDONIAN ORTHODOX TRADITION 18 A1.21 Nestorian Family – Church of the East 18 A1.22 Monophysite Family 19 A1.23 Coptic Church Family 19 A1.30 INTRA-FAITH ORTHODOX ORGANIZATIONS 20 A2.0 WESTERN LITURGICAL TRADITION 20 A2.1 Roman Catholic Church 21 A2.2 Religious Orders of the Roman Catholic Church 21 A2.3 Autonomous Orthodox Churches in communion with the Vatican 21 A2.4 Old Catholic Church Movement 23 A2.5 Other -

Faith and Belief Codes

Faith and Belief Codes as of 7/21/2017 Code Description Start Date End Date A1 Protestant Episcopal Church 20170331 A2 Independent Baptist Bible Mission 20170331 A3 Baptist Bible Fellowship 20170331 A4 Ohio Yearly Meeting of Friends 20170331 A5 Kansas Yearly Meeting of Friends 20170331 A6 Anglican Orthodox Church 20170331 A7 Messianic 20170331 AC Advent Christian Church AD Eckankar 20170331 AH Heathen 20170331 AJ Jehovah’s Witnesses AK Korean Evangelical Church of America 20170331 AM Christian Crusade 20170331 AN Native American AO Brethren In Christ Fellowship 20170331 AR American Baptist Convention 20170331 AS Seventh Day Adventists AT Baptist General Conference 20170331 AV Adventist Churches AX Bible Presbyterian Church 20170331 AY Church of The Spiral Tree 20170331 B1 Southern Methodist Church 20170331 B2 Reformed Churches 20170331 B3 Grace Gospel Fellowship 20170331 B4 American Baptist Association 20170331 B5 Congregational Methodist Church 20170331 B6 Conservative Baptist Association of America 20170331 B7 General Conference of the Swedenborgian Church 20170331 B9 Association of Free Lutheran Congregations 20170331 BA American Baptist Churches In USA BB Baptist Churches BC Southern Baptist Convention BE Armenian Apostolic 20170331 BF Free Will Baptist Churches, Other BG General Association of General Baptists BH Fundamental Methodist Church Inc. 20170331 BI United Presbyterian Church In The USA 20170331 BN National Baptist Convention of America BP Progressive National Baptist Convention BR General Association of Regular Baptist -

QUESTIONNAIRE May 30, 2014

1 PEW RESEARCH CENTER PEW RESEARCH CENTER 2014 RELIGIOUS LANDSCAPE STUDY (RLS-II) MAIN SURVEY OF NATIONALLY REPRESENTATIVE SAMPLE OF ADULTS FINAL QUESTIONNAIRE May 30, 2014 NOTE: THIS DOCUMENT INCLUDES QUESTIONS THAT WERE RELEASED AS PART OF THE FIRST OR SECOND REPORTS ON THE FINDINGS OF THE RELIGIOUS LANDSCAPE STUDY, THOSE RELEASED AS PART OF “RELIGION IN EVERYDAY LIFE” AND THOSE RELEASED AS PART OF “ONE-IN-FIVE U.S. ADULTS WERE RAISED IN INTERFAITH HOMES.” SOME QUESTIONS HAVE BEEN HELD FOR FUTURE RELEASE, AS INDICATED BELOW. Guide to questions on the RLS-II interactive website: An interactive website was released in conjunction with the Religious Landscape Study reports. The list below shows which questions can be analyzed using the website and what short description the website used for each question. Short Description on Website Question number Age AGE Generation AGE Gender SEX Race and Ethnicity HISP, RACE Immigration Status Q.P2, Q.P6, Q.P7 Income INCOME Education EDUC Marital Status MARITAL Parental Status CHILDREN Belief in God Q.G1, Q.G1b Importance of Religion Q.F2 Attendance at Religious Services ATTEND Prayer Frequency Q.I1 Prayer Groups Q.I2a Meditation Q.I2c Feelings of Spiritual Well-Being Q.I4a Feelings of Sense of Wonder Q.I4b Guidance on Right and Wrong Q.B31 Standards for Right and Wrong Q.B2d Reading Scripture Q.I2b Interpretation of Scripture Q.G7, Q.G7b Belief in Heaven Q.G5 Belief in Hell Q.G6 Political Party PARTY, PARTYLN Political Ideology IDEO Size of Government Q.B20 Government Aid to the Poor Q.B2b Abortion Q.B21 Homosexuality Q.B2a Same-Sex Marriage Q.B22 Protecting the Environment Q.B2c Human Evolution Q.B30, Q.B30b www.pewresearch.org 2 PEW RESEARCH CENTER Full text of question wording: LANDLINE INTRO: Hello, I am _____ calling on behalf of the Pew Research Center. -

The Anglican House Church in Theology and Context

LIBERTY UNIVERSITY BAPTIST THEOLOGICAL SEMINARY SACRA DOMUS: THE ANGLICAN HOUSE CHURCH IN THEOLOGY AND CONTEXT A Thesis Project Submitted to Liberty University Baptist Theological Seminary in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree DOCTOR OF MINISTRY By Alan L. Andraeas Lynchburg, Virginia May, 2014 Copyright © 2014 Alan L. Andraeas All Rights Reserved LIBERTY UNIVERSITY BAPTIST THEOLOGICAL SEMINARY THESIS PROJECT APPROVAL SHEET GRADE: MENTOR: READER: To Susan ABSTRACT SACRA DOMUS: THE ANGLICAN HOUSE CHURCH IN THEOLOGY AND CONTEXT Alan L. Andraeas Liberty University Baptist Theological Seminary, 2014 Mentor: Dr. Vernon Whaley The author is an evangelical Anglican priest with a recently formed sacramental house church. Though the house church movement is gaining popularity, no formal guidelines or methodologies exist which address this trend from a liturgical and sacerdotal perspective—even within his diocese. Because of this void, he will examine the following critical issues: What are the scriptural foundations for mandating the use of liturgy? What are the biblical, theological, and historical precedents for house churches? Can there be a complementary union between priestly liturgy and the house church model? Without guidance from other ‘reference parishes,’ the need for such a methodology will be demonstrated. Survey data demonstrating how other Anglican communions have wrestled with this church model will also be investigated. Recommendations will then be made for future research to aid the Anglican house church and its chief act of worship: the celebration of the Eucharist. Abstract length: 142 words. CONTENTS PREFACE vii ACKNOWLEDGMENTS xi Chapter 1. Introduction 1 Statement of Limitations 4 Theoretical Basis for the Project 6 Statement of Methodology 7 Summary 11 Chapter 2.