Hummingbird Flight Speeds

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Topazes and Hermits

Trochilidae I: Topazes and Hermits Fiery Topaz, Topaza pyra Topazini Crimson Topaz, Topaza pella Florisuginae White-necked Jacobin, Florisuga mellivora Florisugini Black Jacobin, Florisuga fusca White-tipped Sicklebill, Eutoxeres aquila Eutoxerini Buff-tailed Sicklebill, Eutoxeres condamini Saw-billed Hermit, Ramphodon naevius Bronzy Hermit, Glaucis aeneus Phaethornithinae Rufous-breasted Hermit, Glaucis hirsutus ?Hook-billed Hermit, Glaucis dohrnii Threnetes ruckeri Phaethornithini Band-tailed Barbthroat, Pale-tailed Barbthroat, Threnetes leucurus ?Sooty Barbthroat, Threnetes niger ?Broad-tipped Hermit, Anopetia gounellei White-bearded Hermit, Phaethornis hispidus Tawny-bellied Hermit, Phaethornis syrmatophorus Mexican Hermit, Phaethornis mexicanus Long-billed Hermit, Phaethornis longirostris Green Hermit, Phaethornis guy White-whiskered Hermit, Phaethornis yaruqui Great-billed Hermit, Phaethornis malaris Long-tailed Hermit, Phaethornis superciliosus Straight-billed Hermit, Phaethornis bourcieri Koepcke’s Hermit, Phaethornis koepckeae Needle-billed Hermit, Phaethornis philippii Buff-bellied Hermit, Phaethornis subochraceus Scale-throated Hermit, Phaethornis eurynome Sooty-capped Hermit, Phaethornis augusti Planalto Hermit, Phaethornis pretrei Pale-bellied Hermit, Phaethornis anthophilus Stripe-throated Hermit, Phaethornis striigularis Gray-chinned Hermit, Phaethornis griseogularis Black-throated Hermit, Phaethornis atrimentalis Reddish Hermit, Phaethornis ruber ?White-browed Hermit, Phaethornis stuarti ?Dusky-throated Hermit, Phaethornis squalidus Streak-throated Hermit, Phaethornis rupurumii Cinnamon-throated Hermit, Phaethornis nattereri Little Hermit, Phaethornis longuemareus ?Tapajos Hermit, Phaethornis aethopygus ?Minute Hermit, Phaethornis idaliae Polytminae: Mangos Lesbiini: Coquettes Lesbiinae Coeligenini: Brilliants Patagonini: Giant Hummingbird Lampornithini: Mountain-Gems Tro chilinae Mellisugini: Bees Cynanthini: Emeralds Trochilini: Amazilias Source: McGuire et al. (2014).. -

The Best of Costa Rica March 19–31, 2019

THE BEST OF COSTA RICA MARCH 19–31, 2019 Buffy-crowned Wood-Partridge © David Ascanio LEADERS: DAVID ASCANIO & MAURICIO CHINCHILLA LIST COMPILED BY: DAVID ASCANIO VICTOR EMANUEL NATURE TOURS, INC. 2525 WALLINGWOOD DRIVE, SUITE 1003 AUSTIN, TEXAS 78746 WWW.VENTBIRD.COM THE BEST OF COSTA RICA March 19–31, 2019 By David Ascanio Photo album: https://www.flickr.com/photos/davidascanio/albums/72157706650233041 It’s about 02:00 AM in San José, and we are listening to the widespread and ubiquitous Clay-colored Robin singing outside our hotel windows. Yet, it was still too early to experience the real explosion of bird song, which usually happens after dawn. Then, after 05:30 AM, the chorus started when a vocal Great Kiskadee broke the morning silence, followed by the scratchy notes of two Hoffmann´s Woodpeckers, a nesting pair of Inca Doves, the ascending and monotonous song of the Yellow-bellied Elaenia, and the cacophony of an (apparently!) engaged pair of Rufous-naped Wrens. This was indeed a warm welcome to magical Costa Rica! To complement the first morning of birding, two boreal migrants, Baltimore Orioles and a Tennessee Warbler, joined the bird feast just outside the hotel area. Broad-billed Motmot . Photo: D. Ascanio © Victor Emanuel Nature Tours 2 The Best of Costa Rica, 2019 After breakfast, we drove towards the volcanic ring of Costa Rica. Circling the slope of Poas volcano, we eventually reached the inspiring Bosque de Paz. With its hummingbird feeders and trails transecting a beautiful moss-covered forest, this lodge offered us the opportunity to see one of Costa Rica´s most difficult-to-see Grallaridae, the Scaled Antpitta. -

Volume 2. Animals

AC20 Doc. 8.5 Annex (English only/Seulement en anglais/Únicamente en inglés) REVIEW OF SIGNIFICANT TRADE ANALYSIS OF TRADE TRENDS WITH NOTES ON THE CONSERVATION STATUS OF SELECTED SPECIES Volume 2. Animals Prepared for the CITES Animals Committee, CITES Secretariat by the United Nations Environment Programme World Conservation Monitoring Centre JANUARY 2004 AC20 Doc. 8.5 – p. 3 Prepared and produced by: UNEP World Conservation Monitoring Centre, Cambridge, UK UNEP WORLD CONSERVATION MONITORING CENTRE (UNEP-WCMC) www.unep-wcmc.org The UNEP World Conservation Monitoring Centre is the biodiversity assessment and policy implementation arm of the United Nations Environment Programme, the world’s foremost intergovernmental environmental organisation. UNEP-WCMC aims to help decision-makers recognise the value of biodiversity to people everywhere, and to apply this knowledge to all that they do. The Centre’s challenge is to transform complex data into policy-relevant information, to build tools and systems for analysis and integration, and to support the needs of nations and the international community as they engage in joint programmes of action. UNEP-WCMC provides objective, scientifically rigorous products and services that include ecosystem assessments, support for implementation of environmental agreements, regional and global biodiversity information, research on threats and impacts, and development of future scenarios for the living world. Prepared for: The CITES Secretariat, Geneva A contribution to UNEP - The United Nations Environment Programme Printed by: UNEP World Conservation Monitoring Centre 219 Huntingdon Road, Cambridge CB3 0DL, UK © Copyright: UNEP World Conservation Monitoring Centre/CITES Secretariat The contents of this report do not necessarily reflect the views or policies of UNEP or contributory organisations. -

Alpha Codes for 2168 Bird Species (And 113 Non-Species Taxa) in Accordance with the 62Nd AOU Supplement (2021), Sorted Taxonomically

Four-letter (English Name) and Six-letter (Scientific Name) Alpha Codes for 2168 Bird Species (and 113 Non-Species Taxa) in accordance with the 62nd AOU Supplement (2021), sorted taxonomically Prepared by Peter Pyle and David F. DeSante The Institute for Bird Populations www.birdpop.org ENGLISH NAME 4-LETTER CODE SCIENTIFIC NAME 6-LETTER CODE Highland Tinamou HITI Nothocercus bonapartei NOTBON Great Tinamou GRTI Tinamus major TINMAJ Little Tinamou LITI Crypturellus soui CRYSOU Thicket Tinamou THTI Crypturellus cinnamomeus CRYCIN Slaty-breasted Tinamou SBTI Crypturellus boucardi CRYBOU Choco Tinamou CHTI Crypturellus kerriae CRYKER White-faced Whistling-Duck WFWD Dendrocygna viduata DENVID Black-bellied Whistling-Duck BBWD Dendrocygna autumnalis DENAUT West Indian Whistling-Duck WIWD Dendrocygna arborea DENARB Fulvous Whistling-Duck FUWD Dendrocygna bicolor DENBIC Emperor Goose EMGO Anser canagicus ANSCAN Snow Goose SNGO Anser caerulescens ANSCAE + Lesser Snow Goose White-morph LSGW Anser caerulescens caerulescens ANSCCA + Lesser Snow Goose Intermediate-morph LSGI Anser caerulescens caerulescens ANSCCA + Lesser Snow Goose Blue-morph LSGB Anser caerulescens caerulescens ANSCCA + Greater Snow Goose White-morph GSGW Anser caerulescens atlantica ANSCAT + Greater Snow Goose Intermediate-morph GSGI Anser caerulescens atlantica ANSCAT + Greater Snow Goose Blue-morph GSGB Anser caerulescens atlantica ANSCAT + Snow X Ross's Goose Hybrid SRGH Anser caerulescens x rossii ANSCAR + Snow/Ross's Goose SRGO Anser caerulescens/rossii ANSCRO Ross's Goose -

Use of Floral Nectar in Heliconia Stilesii Daniels by Three Species of Hermit Hummingbirds

The Condor89~779-787 0 The Cooper OrnithologicalSociety 1987 ECOLOGICAL FITTING: USE OF FLORAL NECTAR IN HELICONIA STILESII DANIELS BY THREE SPECIES OF HERMIT HUMMINGBIRDS FRANK B. GILL The Academyof Natural Sciences,Philadelphia, PA 19103 Abstract. Three speciesof hermit hummingbirds-a specialist(Eutoxeres aquikz), a gen- eralist (Phaethornissuperciliosus), and a thief (Threnetesruckerz]-visited the nectar-rich flowers of Heliconia stilesii Daniels at a lowland study site on the Osa Peninsula of Costa Rica. Unlike H. pogonanthaCufodontis, a related Caribbean lowland specieswith a less specialized flower, H. stilesii may not realize its full reproductive potential at this site, becauseit cannot retain the services of alternative pollinators such as Phaethornis.The flowers of H. stilesii appear adapted for pollination by Eutoxeres, but this hummingbird rarely visited them at this site. Lek male Phaethornisvisited the flowers frequently in late May and early June, but then abandonedthis nectar sourcein favor of other flowers offering more accessiblenectar. The strong curvature of the perianth prevents accessby Phaethornis to the main nectar chamber; instead they obtain only small amounts of nectar that leaks anteriorly into the belly of the flower. Key words: Hummingbird; pollination; mutualism;foraging; Heliconia stilesii; nectar. INTRODUCTION Ultimately affectedare the hummingbird’s choice Species that expand their distribution following of flowers and patterns of competition among speciationenter novel ecologicalassociations un- hummingbird species for nectar (Stiles 1975, related to previous evolutionary history and face 1978; Wolf et al. 1976; Feinsinger 1978; Gill the challenges of adjustment to new settings, 1978). Use of specificHeliconia flowers as sources called “ecological fitting” (Janzen 1985a). In the of nectar by particular species of hermit hum- case of mutualistic species, such as plants and mingbirds, however, varies seasonally and geo- their pollinators, new ecological settingsmay in- graphically (Stiles 1975). -

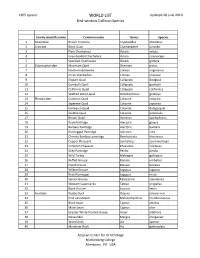

WORLD LIST Updated 28 June 2019 Bird-Window Collision Species

1305 species WORLD LIST Updated 28 June 2019 Bird-window Collision Species Family scientific name Common name Genus Species 1 Tinamidae Brown Tinamou Crypturellus obsoletus 2 Cracidae Black Guan Chamaepetes unicolor 3 Plain Chachalaca Ortalis vetula 4 Grey-headed Chachalaca Ortalis cinereiceps 5 Speckled Chachalaca Ortalis guttata 6 Odontophoridae Mountain Quail Oreortyx pictus 7 Northern Bobwhite Colinus virginianus 8 Crested Bobwhite Colinus cristatus 9 Elegant Quail Callipepla douglasii 10 Gambel's Quail Callipepla gambelii 11 California Quail Callipepla californica 12 Spotted Wood-quail Odontophorus guttatus 13 Phasianidae Common Quail Coturnix coturnix 14 Japanese Quail Coturnix japonica 15 Harlequin Quail Coturnix delegorguei 16 Stubble Quail Coturnix pectoralis 17 Brown Quail Synoicus ypsilophorus 18 Rock Partridge Alectoris graeca 19 Barbary Partridge Alectoris barbara 20 Red-legged Partridge Alectoris rufa 21 Chinese Bamboo-partridge Bambusicola thoracicus 22 Copper Pheasant Syrmaticus soemmerringii 23 Common Pheasant Phasianus colchicus 24 Grey Partridge Perdix perdix 25 Wild Turkey Meleagris gallopavo 26 Ruffed Grouse Bonasa umbellus 27 Hazel Grouse Bonasa bonasia 28 Willow Grouse Lagopus lagopus 29 Rock Ptarmigan Lagopus muta 30 Spruce Grouse Falcipennis canadensis 31 Western Capercaillie Tetrao urogallus 32 Black Grouse Lyrurus tetrix 33 Anatidae Ruddy Duck Oxyura jamaicensis 34 Pink-eared Duck Malacorhynchus membranaceus 35 Black Swan Cygnus atratus 36 Mute Swan Cygnus olor 37 Greater White-fronted Goose Anser albifrons 38 -

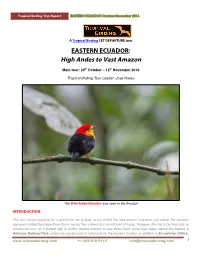

High Andes to Vast Amazon

Tropical Birding Trip Report EASTERN ECUADOR October-November 2016 A Tropical Birding SET DEPARTURE tour EASTERN ECUADOR: High Andes to Vast Amazon Main tour: 29th October – 12th November 2016 Tropical Birding Tour Leader: Jose Illanes This Wire-tailed Manakin was seen in the Amazon INTRODUCTION: This was always going to be a special for me to lead, as we visited the area where I was born and raised, the Amazon, and even visited the lodge there that is run by the community I am still part of today. However, this trip is far from only an Amazonian tour, as it started high in Andes (before making its way down there some days later), above the treeline at Antisana National Park, where we saw Ecuador’s national bird, the Andean Condor, in addition to Ecuadorian Hillstar, 1 www.tropicalbirding.com +1-409-515-9110 [email protected] Page Tropical Birding Trip Report EASTERN ECUADOR October-November 2016 Carunculated Caracara, Black-faced Ibis, Silvery Grebe, and Giant Hummingbird. Staying high up in the paramo grasslands that dominate above the treeline, we visited the Papallacta area, which led us to different high elevation species, like Giant Conebill, Tawny Antpitta, Many-striped Canastero, Blue-mantled Thornbill, Viridian Metaltail, Scarlet-bellied Mountain-Tanager, and Andean Tit-Spinetail. Our lodging area, Guango, was also productive, with White-capped Dipper, Torrent Duck, Buff-breasted Mountain Tanager, Slaty Brushfinch, Chestnut-crowned Antpitta, as well as hummingbirds like, Long-tailed Sylph, Tourmaline Sunangel, Glowing Puffleg, and the odd- looking Sword-billed Hummingbird. Having covered these high elevation, temperate sites, we then drove to another lodge (San Isidro) downslope in subtropical forest lower down. -

Distribution of Iridescent Colours in Hummingbird Communities Results

Distribution of iridescent colours in hummingbird communities results from the interplay between selection for camouflage and communication Hugo Gruson, Marianne Elias, Juan Parra, Christine Andraud, Serge Berthier, Claire Doutrelant, Doris Gomez To cite this version: Hugo Gruson, Marianne Elias, Juan Parra, Christine Andraud, Serge Berthier, et al.. Distribution of iridescent colours in hummingbird communities results from the interplay between selection for camouflage and communication. 2020. hal-02372238v2 HAL Id: hal-02372238 https://hal.archives-ouvertes.fr/hal-02372238v2 Preprint submitted on 3 Feb 2020 HAL is a multi-disciplinary open access L’archive ouverte pluridisciplinaire HAL, est archive for the deposit and dissemination of sci- destinée au dépôt et à la diffusion de documents entific research documents, whether they are pub- scientifiques de niveau recherche, publiés ou non, lished or not. The documents may come from émanant des établissements d’enseignement et de teaching and research institutions in France or recherche français ou étrangers, des laboratoires abroad, or from public or private research centers. publics ou privés. Copyright RESEARCH ARTICLE Open Access Distribution of iridescent colours in Open Peer-Review hummingbird communities results Open Data from the interplay between Open Code selection for camouflage and communication Cite as: Hugo G, Marianne E, Juan L. P, Christine A, Serge B, Claire D, and Doris G. Distribution of iridescent colours in hummingbird communities results from the interplay between Hugo Gruson1, Marianne Elias2, Juan L. Parra3, Christine selection for camouflage and communication. BioRxiv 586362, v5 4 5 1 peer-reviewed and recommended by PCI Andraud , Serge Berthier , Claire Doutrelant , & Doris Evolutionary Biology (2019). -

Breeds on Islands and Along Coasts of the Chukchi and Bering

FAMILY PTEROCLIDIDAE 217 Notes.--Also known as Common Puffin and, in Old World literature, as the Puffin. Fra- tercula arctica and F. corniculata constitutea superspecies(Mayr and Short 1970). Fratercula corniculata (Naumann). Horned Puffin. Mormon corniculata Naumann, 1821, Isis von Oken, col. 782. (Kamchatka.) Habitat.--Mostly pelagic;nests on rocky islandsin cliff crevicesand amongboulders, rarely in groundburrows. Distribution.--Breedson islandsand alongcoasts of the Chukchiand Bering seasfrom the DiomedeIslands and Cape Lisburnesouth to the AleutianIslands, and alongthe Pacific coast of western North America from the Alaska Peninsula and south-coastal Alaska south to British Columbia (QueenCharlotte Islands, and probablyelsewhere along the coast);and in Asia from northeasternSiberia (Kolyuchin Bay) southto the CommanderIslands, Kam- chatka,Sakhalin, and the northernKuril Islands.Nonbreeding birds occurin late springand summer south along the Pacific coast of North America to southernCalifornia, and north in Siberia to Wrangel and Herald islands. Winters from the Bering Sea and Aleutians south, at least casually,to the northwestern Hawaiian Islands (from Kure east to Laysan), and off North America (rarely) to southern California;and in Asia from northeasternSiberia southto Japan. Accidentalin Mackenzie (Basil Bay); a sight report for Baja California. Notes.--See comments under F. arctica. Fratercula cirrhata (Pallas). Tufted Puffin. Alca cirrhata Pallas, 1769, Spic. Zool. 1(5): 7, pl. i; pl. v, figs. 1-3. (in Mari inter Kamtschatcamet -

The Hummingbirds of Nariño, Colombia

The hummingbirds of Nariño, Colombia Paul G. W. Salaman and Luis A. Mazariegos H. El departamento de Nariño en el sur de Colombia expande seis Areas de Aves Endemicas y contiene una extraordinaria concentración de zonas de vida. En años recientes, el 10% de la avifauna mundial ha sido registrada en Nariño (similar al tamaño de Belgica) aunque ha recibido poca atención ornitólogica. Ninguna familia ejemplifica más la diversidad Narinense como los colibríes, con 100 especies registradas en siete sitios de fácil acceso en Nariño y zonas adyacentes del Putumayo. Cinco nuevas especies de colibríes para Colombia son presentadas (Campylopterus villaviscensio, Heliangelus strophianus, Oreotrochilus chimborazo, Patagona gigas, y Acestrura bombus), junto con notas de especies pobremente conocidas y varias extensiones de rango. Una estabilidad regional y buena infraestructura vial hacen de Nariño un “El Dorado” para observadores de aves y ornitólogos. Introduction Colombia’s southern Department of Nariño covers c.33,270 km2 (similar in size to Belgium or one quarter the size of New York state) from the Pacific coast to lowland Amazonia and spans the Nudo de los Pastos massif at 4,760 m5. Six Endemic Bird Areas (EBAs 39–44)9 and a diverse range of life zones, from arid tropical forest to the wettest forests in the world, are easily accessible. Several researchers, student expeditions and birders have visited Nariño and adjacent areas of Putumayo since 1991, making several notable ornithological discoveries including a new species—Chocó Vireo Vireo masteri6—and the rediscovery of several others, e.g. Plumbeous Forest-falcon Micrastur plumbeus, Banded Ground-cuckoo Neomorphus radiolosus and Tumaco Seedeater Sporophila insulata7. -

Bioone COMPLETE

BioOne COMPLETE Introduction to the Skeleton of Hummingbirds (Aves: Apodiformes, Trochilidae) in Functional and Phylogenetic Contexts Author: Zusi, Richard L., Division of Birds, National Museum of Natural History, P.O. Box 37012, Smithsonian Institution, Washington, D.C. 20013, USA Source: Ornithological Monographs No. 77 Published By: American Ornithological Society URL: https://doi.org/10.1525/om.2013.77.L1 BioOne Complete (complete.BioOne.org) is a full-text database of 200 subscribed and open-access titles in the biological, ecological, and environmental sciences published by nonprofit societies, associations, museums, institutions, and presses. Your use of this PDF, the BioOne Complete website, and all posted and associated content indicates your acceptance of BioOne's Terms of Use, available at www.bioone.org/terms-of-use. Usage of BioOne Complete content is strictly limited to personal, educational, and non-commercial use. Commercial inquiries or rights and permissions requests should be directed to the individual publisher as copyright holder. BioOne sees sustainable scholarly publishing as an inherently collaborative enterprise connecting authors, nonprofit publishers, academic institutions, research libraries, and research funders in the common goal of maximizing access to critical research. Downloaded From: https://bioone.org/ebooks on 1/14/2019 Terms of Use: https://bioone.org/terms-of-use Access provided by University of New Mexico Ornithological Monographs Volume (2013), No. 77, 1-94 © The American Ornithologists' Union, 2013. Printed in USA. INTRODUCTION TO THE SKELETON OF HUMMINGBIRDS (AVES: APODIFORMES, TROCHILIDAE) IN FUNCTIONAL AND PHYLOGENETIC CONTEXTS R ic h a r d L. Z u s i1 Division of Birds, National Museum of Natural History, P.O. -

Demography and Habitat Use of Cerulean Warblers on Breeding

DEMOGRAPHY AND HABITAT USE OF CERULEAN WARBLERS ON BREEDING AND WINTERING GROUNDS A Dissertation Presented in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree Doctor of Philosophy in the Graduate School of The Ohio State University By Marja H. Bakermans, M.S. ***** The Ohio State University 2008 Dissertation Committee: Dr. Amanda D. Rodewald, Adviser Dr. Kendra McSweeney Approved by Dr. Lisa Petit Dr. Paul Rodewald ____________________________ Adviser Graduate Program in Natural Resources ABSTRACT Because their annual movements span continents, Nearctic-Neotropical migratory birds represent one of the most challenging groups for which effective conservation strategies can be developed. Knowledge of the ecology and management of migratory bird communities comes primarily from studies conducted on the breeding grounds. However, recent work demonstrates that events that occur throughout the annual cycle may also contribute to population declines. The Cerulean Warbler (Dendroica cerulea), a Neotropical migrant exhibiting precipitous population declines, is an excellent example of a species that may be impacted by events on both the breeding and nonbreeding grounds. My dissertation research examined habitat use and population demography of Cerulean Warblers on breeding (southern Ohio) and wintering (Venezuelan Andes) grounds to evaluate potential factors that contribute to declines in Cerulean Warblers. During the breeding season, we surveyed Cerulean Warblers across 12 mature forest sites in southeast Ohio, 2004-2006. Research on the breeding grounds identified 1) how clearcutting impacted spatial distribution, density, and nesting success of Cerulean Warblers at multiple spatial scales (i.e., from local/edge to landscape), and 2) specific microhabitat and nest-patch characteristics selected by Cerulean Warblers. At each site, Ceruleans were intensively spot-mapped 8 times each year from May to July, adult behavior was used to locate and monitor nesting attempts, and nest, local, and ii landscape habitat characteristics were quantified.