Montana Petition

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Free Silver"; Montana's Political Dream of Economic Prosperity, 1864-1900

University of Montana ScholarWorks at University of Montana Graduate Student Theses, Dissertations, & Professional Papers Graduate School 1969 "Free silver"; Montana's political dream of economic prosperity, 1864-1900 James Daniel Harrington The University of Montana Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarworks.umt.edu/etd Let us know how access to this document benefits ou.y Recommended Citation Harrington, James Daniel, ""Free silver"; Montana's political dream of economic prosperity, 1864-1900" (1969). Graduate Student Theses, Dissertations, & Professional Papers. 1418. https://scholarworks.umt.edu/etd/1418 This Thesis is brought to you for free and open access by the Graduate School at ScholarWorks at University of Montana. It has been accepted for inclusion in Graduate Student Theses, Dissertations, & Professional Papers by an authorized administrator of ScholarWorks at University of Montana. For more information, please contact [email protected]. "FREE SILVER MONTANA'S POLITICAL DREAM OF ECONOMIC PROSPERITY: 1864-19 00 By James D. Harrington B. A. Carroll College, 1961 Presented in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Master of Arts UNIVERSITY OF MONTANA 1969 Approved by: Chairman, Board of Examiners . /d . Date UMI Number: EP36155 All rights reserved INFORMATION TO ALL USERS The quality of this reproduction is dependent upon the quality of the copy submitted. In the unlikely event that the author did not send a complete manuscript and there are missing pages, these will be noted. Also, if material had to be removed, a note will indicate the deletion. UMT Disaartation Publishing UMI EP36155 Published by ProQuest LLC (2012). Copyright in the Dissertation held by the Author. -

COLUMN: Natelson Will Leave Legacy of Strong Conservative Base in Montana | State & Regional | Missoulian.Com

2/17/2021 COLUMN: Natelson will leave legacy of strong conservative base in Montana | State & Regional | missoulian.com https://missoulian.com/news/state-and-regional/column-natelson-will-leave-legacy-of-strong-conservative-base- in-montana/article_2a9311fa-13b0-11df-837a-001cc4c002e0.html COLUMN: Natelson will leave legacy of strong conservative base in Montana By CHARLES S. JOHNSON Missoulian State Bureau Feb 7, 2010 Rob Natelson KURT WILSON/Missoulian By CHARLES S. JOHNSON Missoulian State Bureau https://missoulian.com/news/state-and-regional/column-natelson-will-leave-legacy-of-strong-conservative-base-in/article_2a9311fa-13b0-11df-837a-… 1/4 2/17/2021 COLUMN: Natelson will leave legacy of strong conservative base in Montana | State & Regional | missoulian.com ELENA - When he moves to Colorado this summer, Rob Natelson will leave H behind a much-revitalized Montana conservative movement that he helped foment and lead over much of the past two decades. The anti-tax increase, lower-government spending and pro-free market philosophies that Natelson has advocated are now firmly embedded in the mainstream of the Montana Republican Party and with most GOP legislators. That wasn't necessarily the case when Natelson began speaking out here. Natelson, 61, said recently he will resign his job as a law professor at the University of Montana and take a job at the Independence Institute, a Colorado-based think tank that advocates free-market solutions to public policy issues. He has taught at the UM law school since 1987. Although he's been less active politically more recently to concentrate on his teaching, Natelson over the years has been a prominent political crusader, participant and commentator. -

Of the Federal Election Commission, and Counsel to Senator John Mccain’S 2000 Presidential Campaign

The Case for Closing the Federal Election Commission and Establishing a New System for Enforcing the Nation’s Campaign Finance Laws Project FEC | 2002 Table of Contents Introduction . .1 Part I What’s Wrong With The FEC: The Case for Closing the Federal Election Commission . .5 Part II Recommendations: Creating a New System for Enforcing the Nation’s Campaign Finance Laws . .33 Part III Case Studies: Detailing the Problems . .47 Exhibit 1. The Structure of the Commission: Weak, Slow-Footed, and Ineffectual . 49 Exhibit 2. The Commissioners: Party Machinery . .59 Exhibit 3. Congressional Interference: Muzzled Watchdog . .71 Exhibit 4. Soft Money: The Half-Billion Dollar Scandal Staged by the FEC . .81 Exhibit 5. Other Problems Created by the FEC: “Coordination,” Convention Funding, “Building Funds,” and Enforcement . .97 Exhibit 6. The Role of the Courts in Campaign Finance Law: No Excuses Here for the FEC . .117 Endnotes . .125 Introduction No Bark, No Bite, No Point. The Case for Closing the Federal Election Commission and Establishing a New System for Enforcing the Nation’s Campaign Finance Laws Introduction The Federal Election Commission (FEC) is beset with a constellation of problems that has resulted in its failure to act as a “real law enforcement agency.”1 Among the major reasons for this failure are the ineffectual structure of the Commission, the politicization of the appoint- ment of commissioners, and congressional interference with the agency. In the fall of 2000, Democracy 21 Education Fund initiated PROJECT FEC to develop and introduce into the national debate a new and comprehensive approach for effectively enforcing the nation’s campaign finance laws. -

The Evolution of the Digital Political Advertising Network

PLATFORMS AND OUTSIDERS IN PARTY NETWORKS: THE EVOLUTION OF THE DIGITAL POLITICAL ADVERTISING NETWORK Bridget Barrett A thesis submitted to the faculty at the University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Master of Arts at the Hussman School of Journalism and Media. Chapel Hill 2020 Approved by: Daniel Kreiss Adam Saffer Adam Sheingate © 2020 Bridget Barrett ALL RIGHTS RESERVED ii ABSTRACT Bridget Barrett: Platforms and Outsiders in Party Networks: The Evolution of the Digital Political Advertising Network (Under the direction of Daniel Kreiss) Scholars seldom examine the companies that campaigns hire to run digital advertising. This thesis presents the first network analysis of relationships between federal political committees (n = 2,077) and the companies they hired for electoral digital political advertising services (n = 1,034) across 13 years (2003–2016) and three election cycles (2008, 2012, and 2016). The network expanded from 333 nodes in 2008 to 2,202 nodes in 2016. In 2012 and 2016, Facebook and Google had the highest normalized betweenness centrality (.34 and .27 in 2012 and .55 and .24 in 2016 respectively). Given their positions in the network, Facebook and Google should be considered consequential members of party networks. Of advertising agencies hired in the 2016 electoral cycle, 23% had no declared political specialization and were hired disproportionately by non-incumbents. The thesis argues their motivations may not be as well-aligned with party goals as those of established political professionals. iii TABLE OF CONTENTS LIST OF TABLES AND FIGURES .................................................................................................................... V POLITICAL CONSULTING AND PARTY NETWORKS ............................................................................... -

Life Before BCRA: Soft Money at the State Level

L I F E B E F O R E B C R A S O F T M O N E Y A T T H E S T A T E L E V E L I N T H E 2 0 0 0 & 2 0 0 2 E L E C T I O N C Y C L E S By D E N I S E B A R B E R T H E I N S T I T U T E O N M O N E Y I N S T A T E P O L I T I C S D E C . 1 7 , 2 0 0 3 1 833 NORTH MAIN, SECOND FLOOR • HELENA, MT • 59601 PHONE 406-449-2480 • FAX 406-457-2091 • E-MAIL [email protected] www.followthemoney.org T A B L E O F C O N T E N T S State Parties: Looking for New Dance Partners ........................................3 Summary of Findings...............................................................................5 State-by-State Rankings ...........................................................................7 Who Gives to State Party Committees? ....................................................9 National Committees: State Party Sugar Daddies ................................... 10 Patterns in Giving....................................................................... 11 Transfers and Trading................................................................. 11 Reporting Discrepancies ............................................................. 13 Top Individual Contributors ................................................................... 14 Interstate Trading of Soft Money............................................................ 19 Top Industries ........................................................................................ 21 Tables ........................................................................................................ Table 1: Soft-Money Contributions, 2000 and 2002......................7 Table 2: Types of Contributors to State Party Committees ............9 Table 3: Soft Money from the National Committees ................... 10 Table 4: Top 25 Individual Contributors of Soft Money.............. 16 Table 5: Top 30 Industries Contributing to State Parties............. -

The Riverwatch the Quarterly Newsletter of the Anglers of the Au Sable

Winter 2014 Number 68 THE RIVERWATCH THE QUARTERLY NEWSLETTER OF THE ANGLERS OF THE AU SABLE Tom Baird wraps up the Holy Water Mineral Lease action and charts the remaining steps to addressing our concerns regarding oil and gas development FROM THE EDITOR BRINGING IT ALL BACK HOME ASBWPA TO MERGE WITH ANGLERS It’s time to join forces. out below Mio, their primary mission of caring for the Holy Water, North Branch and South Branch made the The Au Sable Big Water Preservation Association will problems below the Dam secondary. There are, after all, merge with Anglers of the Au Sable. Both Boards are in so many hours in each day. The area needed help from agreement with the idea in principle, and fi nal details of a more localized organization. Lacking any such entity, the merger are being worked out over this long, cold win- I gathered several committed friends and took a hold of ter. As it stands now, the Mio-based organization will be the reigns. offi cially absorbed at midnight September 8th. This will bring an end to the group’s productive seven-year run as We did a lot in a short period with limited people-power river keeper on the Trophy Water. The work that was ini- by expanding cleanups on that heavily used and often tiated during their time will continue under the Anglers’ abused section, conceptualizing the 70 Degree Pledge direction. to address dangerous water temperatures in the summer months (later adding catch-n-release.org to educate folks It’s the right move at the right time. -

B 3 A:,;!138 March 31,1998

:" < GO.--.-.:^:- .1. s:c-^T • b 3 a:,;!138 March 31,1998 Federal Election Commission 999 E. Street, N.W. Washington, D.C. 20463 RE: Federal Election Complaint Against Rick Hill For Congress Committee (1996), Triad Management Services, Inc., Citizens for Reform, and Citizens for the Republic Education Fund Dear Commissioners: This letter is a formal complaint by the Montana Democratic Party against the 1996 Rick Hill for Congress Committee, Helena, Montana, Triad Management Services, Inc., Manassas, Virginia and Citizens for Reform, and Citizens for the Republic Education Fund, Manassas, Virginia. We, the Montana Democratic Party, further request that the Federal Election Commission expedite this investigation and determination of these allegations because of their critical importance to the citizens of Montana and the United States. The 1996 election cycle saw the emergence of a new hybrid, third party election activity which makes a mockery of federal election law. If this type of activity is left unchecked by the Federal Election Commission, we can only expect it to dramatically increase in the future. Information gained from investigations by the U.S. Senate Committee examining alleged election law violations in the 1996 elections documents the creation of a new type of organization funded by a handful of wealthy interests to circumvent election laws. The minority report from that Senate Committee documents the activities of Triad Management Services and how it created two shell organizations, Citizens for Reform and Citizens for the Republic Education Fund, to spend between three and four million dollars in 29 House and Senate races and circumvent election laws. -

![Box-'/. Oversized Flats [Posters, Handbills, Etc] Box __ Political Cartoons Box Textiles Box Photograph Collection Box](https://docslib.b-cdn.net/cover/6210/box-oversized-flats-posters-handbills-etc-box-political-cartoons-box-textiles-box-photograph-collection-box-1666210.webp)

Box-'/. Oversized Flats [Posters, Handbills, Etc] Box __ Political Cartoons Box Textiles Box Photograph Collection Box

This document is from the collections at the Dole Archives, University of Kansas http://dolearchives.ku.edu Robert J. Dole Institute of Politics REMOVAL NOTICE Date: /0 llt 201 ~ . ' J Removed to: Oversized Photographs Box (Circle one) Oversized Publications Box Campaign Material Box Oversized Newsprint Box . · ~ Personal Effects Box Memorabilia Box-'/. Oversized Flats [Posters, Handbills, etc] Box __ Political Cartoons Box Textiles Box Photograph Collection Box ·Restrictions: none Place one copy with removed item Place one copy in original folder File one copy in file Page 1 of 30 This document is from the collections at the Dole Archives, University of Kansas http://dolearchives.ku.edu U.S. SENATE ,/A PROVEN LEADER ,/ dcfs1~lls1XIAN ,/A CARING FAM/LYMAN ATRUE MONTANA VOICE IN WASHINGTON Paid for by KOLSTAD for U.S. Senate Committee,Page Irvin 2 Hutchison, of 30 Treasurer This document is from the collections at the Dole Archives, University of Kansas http://dolearchives.ku.edu A TRUE ONTANA VOICE IN WASHINGTON Reflecting the Conservative Values Shared by Most Montana s As a member of a fifth generation Montana family, as a farmer and small businessman, and as a dedicated public servant for almost 22 years, I have dedicated my life to the well-being of our great state. I think I share the concerns of most Montanans-concerns for our livelihoods, for our environment, for our families and for our country. I am com itted to traditional values and conservative principles. I'm a citizen who feels a genuine obligation to offer the voters of our great st te a credible choice in this important election. -

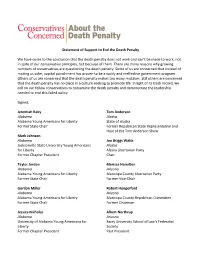

Conservative Statement to End Death Penalty with 250+ Signatories

Statement of Support to End the Death Penalty We have come to the conclusion that the death penalty does not work and can’t be made to work, not in spite of our conservative principles, but because of them. There are many reasons why growing numbers of conservatives are questioning the death penalty. Some of us are concerned that instead of making us safer, capital punishment has proven to be a costly and ineffective government program. Others of us are concerned that the death penalty makes too many mistakes. Still others are concerned that the death penalty has no place in a culture seeking to promote life. In light of its track record, we call on our fellow conservatives to reexamine the death penalty and demonstrate the leadership needed to end this failed policy. Signed, Jeremiah Baky Tom Anderson Alabama Alaska Alabama Young Americans for Liberty State of Alaska Former State Chair Former Republican State Representative and Host of the Tom Anderson Show Mark Johnson Alabama Jon Briggs Watts Jacksonville State University Young Americans Alaska for Liberty Alaska Libertarian Party Former Chapter President Chair Taylor Jordan Merissa Hamilton Alabama Arizona Alabama Young Americans for Liberty Maricopa County Libertarian Party Former State Chair Former Vice-Chair Gordon Miller Robert Hungerford Alabama Arizona Alabama Young Americans for Liberty Maricopa County Republican Committee Former State Chair Former Chairman Jessica Nicholas Albert Northrup Alabama Arizona University of Alabama Young Americans for Barry University School of -

No. ___In the Supreme Court of the United States COREY

No. _________ In the Supreme Court of the United States COREY STAPLETON, MONTANA SECRETARY OF STATE, Applicant, v. THE MONTANA DEMOCRATIC PARTY, TAYLOR BLOSSOM, RYAN FILZ, MADELEINE NEUMEYER, and REBECCA WEED Respondents. On Application to the Honorable Elena Kagan to Stay the Order of the Montana Supreme Court EMERGENCY APPLICATION FOR STAY Jim Renne, Counsel of Record 4201 Wilson Blvd., Ste. 110521 Arlington, VA 22203 [email protected] Matthew T. Meade (admission pending) Smith Oblander & Meade, PC P.O. Box 2685 Great Falls, MT 59403-2685 [email protected] Austin James Secretary of State’s Office P.O. Box 202801 Helena, MT 59620-2801 [email protected] Counsel for Applicant August 24, 2020 PARTIES TO THE PROCEEDING Applicant is Corey Stapleton, Montana Secretary of State (“Secretary”), the defendant before the Montana District Court and the appellant in the Montana Supreme Court. Respondents, Montana Democratic Party (“MDP”) and four individual voters, were plaintiffs at trial and appellees in the Montana Supreme Court. i TABLE OF CONTENTS PARTIES TO THE PROCEEDING i TABLE OF AUTHORITIES iii INTRODUCTION 1 JURISDICTION 3 STATEMENT OF THE CASE 4 A. The Montana Democratic Party filed suit to remove the Green Party from the ballot one day before the state’s primary elections 4 B. The Montana courts have reworked Montana’s minor party petition process at the eleventh hour 6 REASONS FOR GRANTING THE APPLICATION 8 A. There is a reasonable probability that at least four Justices will find certiorari warranted 9 1. The Montana courts have disregarded the First Amendment and this Court’s binding precedent 10 a) Montana courts have created significant undue burdens upon petition proponents 11 b) Montana now has a two-part petition campaign process 14 2. -

This Table Was Published on 4/3/15. Amount PAC Independent

This table was published on 4/3/15. Independent Expenditure Table 1* Independent Expenditure Totals by Committee and Filer Type January 1, 2013 through December 31, 2014 Independent Expenditure (IE) Totals by Committee and Filer Type Amount PAC Independent Expenditures** $48,829,678 Party Independent Expenditures $228,993,297 Independent Expenditure-Only Political Committees $339,402,611 Political Committees with Non-Contribution Accounts $2,573,469 Independent Expenditures Reported by Persons other than Political Committees $168,045,226 Total Independent Expenditures (IE) $787,844,281 ID # IEs by Political Action Committee (PAC)** Amount C00348540 1199 SERVICE EMPLOYEES INT'L UNION FEDERAL POLITICAL ACTION FUND $125,022 C00346015 80-20 NATIONAL ASIAN AMERICAN PAC $900 C00001461 ALASKA STATE MEDICAL ASSOCIATION POLITICAL ACTION COMMITTEE (ALPAC) $14,000 C00235861 ALLEN COUNTY RIGHT TO LIFE INC POLITICAL ACTION COMMITTEE $1,914 C00493221 ALLEN WEST GUARDIAN FUND $1,364,476 C00359539 AMERICAN ACADEMY OF DERMATOLOGY ASSOCIATION POLITICAL ACTION COMMITTEE (SKINPAC)$48,706 C00411553 AMERICAN ACADEMY OF FAMILY PHYSICIANS POLITICAL ACTION COMMITTEE $50,000 C00196246 AMERICAN ACADEMY OF OPHTHALMOLOGY INC POLITICAL COMMITTEE (OPHTHPAC) $334,184 C00173153 AMERICAN ASSOCIATION OF NURSE ANESTHETISTS SEPARATE SEGREGATED FUND (CRNA-PAC)$150,402 C00343459 AMERICAN COLLEGE OF RADIOLOGY ASSOCIATION POLITICAL ACTION COMMITTEE $1,167,715 C00382424 AMERICAN COLLEGE OF SURGEONS PROFESSIONAL ASSOCIATION PAC $200,000 C00011114 AMERICAN FEDERATION OF STATE COUNTY -

Montana Freemason

Montana Freemason Feburary 2013 Volume 86 Number 1 Montana Freemason February 2013 Volume 86 Number 1 Th e Montana Freemason is an offi cial publication of the Grand Lodge of Ancient Free and Accepted Masons of Montana. Unless otherwise noted,articles in this publication express only the private opinion or assertion of the writer, and do not necessarily refl ect the offi cial position of the Grand Lodge. Th e jurisdiction speaks only through the Grand Master and the Executive Board when attested to as offi cial, in writing, by the Grand Secretary. Th e Editorial staff invites contributions in the form of informative articles, reports, news and other timely Subscription - the Montana Freemason Magazine information (of about 350 to 1000 words in length) is provided to all members of the Grand Lodge that broadly relate to general Masonry. Submissions A.F.&A.M. of Montana. Please direct all articles and must be typed or preferably provided in MSWord correspondence to : format, and all photographs or images sent as a .JPG fi le. Only original or digital photographs or graphics Reid Gardiner, Editor that support the submission are accepted. Th e Montana Freemason Magazine PO Box 1158 All material is copyrighted and is the property of Helena, MT 59624-1158 the Grand Lodge of Montana and the authors. [email protected] (406) 442-7774 Deadline for next submission of articles for the next edition is March 30, 2013. Articles submitted should be typed, double spaced and spell checked. Articles are subject to editing and Peer Review. No compensation is permitted for any article or photographs, or other materials submitted for publication.