Palestinian Security Sector Governance

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

University of Cincinnati

U UNIVERSITY OF CINCINNATI Date: 05-20-2009 I, Shadi Y. Saleh , hereby submit this original work as part of the requirements for the degree of: Master in Architecture It is entitled: Designing by Community Participation: Meeting the Challenges of the Palestinian Refugee Camps Shadi Saleh Student Signature: This work and its defense approved by: Committee Chair: Elizabeth Riorden Thomas Bible Approval of the electronic document: I have reviewed the Thesis/Dissertation in its final electronic format and certify that it is an accurate copy of the document reviewed and approved by the committee. Committee Chair signature: Elizabeth Riorden Designing by Community Participation: Meeting the Challenges of the Palestinian Refugee Camps A thesis submitted to the Division of Research and Advance Studies of the University of Cincinnati in partial fulfillment of the requirements of the degree of Master of Architecture In the school of Architecture and Interior design Of the College of Design, Architecture, Art and Planning 2009 By Shadi Y. Saleh Committee chair Elizabeth Riorden Thomas Bible ABSTRACT Palestinian refugee camps in the West Bank, Gaza Strip, Jordan, Lebanon and Syria are the result of the sudden population displacements of 1948 and 1967. After 60 years, unorganized urban growth compounds the situation. The absence of state support pushed the refugees to take matters into their own hands. Currently the camps have problems stemming from both the social situation and the degradation of the built environment. Keeping the refugee camps in order to “represent” a nation in exile does not mean to me that there should be no development. The thesis seeks to make a contribution in solving the social and environmental problems in a way that emphasizes the Right of Return. -

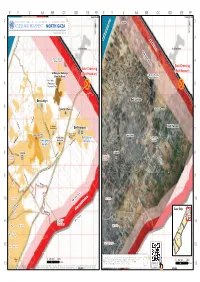

Urban Planning Analyses of Refugee Camps, Jabalia As Case Study-Gaza Strip, Palestine

International Journal of Science and Research (IJSR) ISSN (Online): 2319-7064 Index Copernicus Value (2013): 6.14 | Impact Factor (2015): 6.391 Urban Planning Analyses of Refugee Camps, Jabalia as Case Study-Gaza Strip, Palestine Dr. Usama Ibrahim Badawy1, Dr Ra’ed A. Salha2, Dr. Muain Qasem Jawabrah3, Amjad Jarada4 Mohammed A. EL Hawajri5 1Former Professor of Architecture, Birzeit University Palestine, works currently at UNRWA 2Assistant Professor, Islamic University of Gaza in Geography and GIS Palestine 3Assistance Professor, Architecture Department, Birzeit University Palestine 4Researcher in Infrastructure Planning and Development works currently at UNRWA, G, 5Researcher Geography subjects, works currently as teacher by the Ministry of Education Abstract: The Gaza Strip is a tight area with more than 1.8 million inhabitants. Since the beginning of the last century, and as other Palestinian areas, Gaza Strip was subject to direct occupation. The occupation tightened laws and regulations and increased obstacles, meanwhile it established settlements in a method that besieges existing Palestinian urban areas and leads them to develop in a way that serves the occupation, particularly the security side. This research begins with background information on Palestinian refugees in Gaza, sees that camp Improvement Strategies should called for adoption of the future urban planning, increasing the accommodation capacity of the built-up area, activating the environmental resources protection laws and played down the issue of the land properties when preparing the comprehensive plans. In this study reviews options for addressing the problems faced by Palestinian refugees in Gaza, Recommendations: After discussing the topic through a analyses of the Current Conditions , Land availability, Population distribution, Land requirements, Overcrowding, Public Spaces problems inside the camps , Sustainability in Gaza Strip, socio-economic situation , Unemployment problem and Population density in Jabalia Camp. -

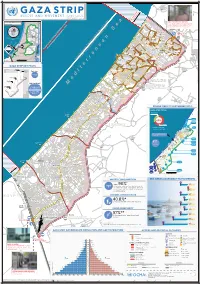

North Gaza ¥ August 2011 ¥ 3 3 Mediterranean Sea No-Go Zone

No Fishing Zone 1.5 nautical miles 3 nautical miles X Y Z AA BB CC DD EE FF X Y Z AA BB CC DD EE FF Yad Mordekhai Yad Mordekhai 2 United Nations OfficeAs-Siafa for the Coordination of Humanitarian Affairs As-Siafa 2 ACCESS AND MOVEMENT - NORTH GAZA ¥ auGUST 2011 ¥ 3 3 Mediterranean Sea No-Go Zone Al-Rasheed Netiv ha-Asara Netiv ha-Asara High Risk Zone Temporary Wastewater 4 Treatment Lagoons 4 Erez Crossing Erez Crossing Al Qaraya al Badawiya (Beit Hanoun) (Beit Hanoun) Al Qaraya al Badawiya (Umm An-Naser) (Umm An-Naser) Beit Lahia 5 Wastewater 5 Treatment Plant Beit Lahiya Beit Lahiya 6 6 'Izbat Beit Hanoun 'Izbat Beit Hanoun Al Mathaf Hotel Al-Sekka Al Karama Al Karama El-Bahar Beit Lahia Main St. Arc-Med Hotel Al-Faloja Sheikh Zayed Beit Hanoun Housing Project Beit Hanoun Madinat al 'Awda 7 v®Madinat al 'Awda 7 Beit Hanoun Jabalia Camp v® Industrial Jabalia Camp 'Arab Maslakh Zone Beit Hanoun 'Arab Maslakh Kamal Edwan Beit Lahya Beit Lahya Abu Ali Eyad Kamal Edwan Hospital Al-Naser Al-Saftawi Hospital Khalil Al-Wazeer Ahmad Sadeq Ash Shati' Camp Said El-Asi Jabalia Jabalia An Naser 8 Al-quds An Naser 8 El-Majadla Ash Sheikh Yousef El-Adama Ash Sheikh Al-Sekka Radwan Radwan Falastin Khalil El-Wazeer Al Deira Hotel Ameen El Husaini Heteen Salah El-Deen ! Al-Yarmook Saleh Dardona Abu Baker Al-Razy Palestine Stadium Al-Shifa Al-Jalaa 9 9 Hospital ! Al-quds Northern Rimal Al-Naffaq Al-Mashahra El-Karama Northern Rimal Omar El-Mokhtar Southern Rimal Al-Wehda Al-Shohada Al Azhar University Ad Daraj G Ad Daraj o v At Tuffah e At Tuffah 10 r 10 n High Risk Zone Islamic ! or Al-Qanal a University Yafa t e Haifa Jamal Abdel Naser Al-Sekka 500 meter NO-Go Zone Salah El-Deen Gaza Strip Beit Lahiya Al-Qahera Khalil Al-Wazeer J" Boundar J" y JabalyaJ" Al-Aqsa As Sabra Gaza City Beit Hanun Gaza City Marzouq GazaJ" City Northern Gaza Al-Dahshan Wire Fence Al 'Umari11 Wastewater 11 Mosque Moshtaha Treatment Plant Tal El Hawa Ijdeedeh Ijdeedeh Deir alJ" Balah Old City Bagdad Old City Rd No. -

Combating Political Violence Movements with Third-Force Options Doron Zimmermann ∗

Between Minimum Force and Maximum Violence: Combating Political Violence Movements with Third-Force Options Doron Zimmermann ∗ Introduction: Balancing the Tools of Counter-Terrorism In most liberal democratic states it is the responsibility of the police forces to cope with “internal” threats, including terrorism, since in such states terrorism is invariably defined as a criminal act rather than a manifestation of insurgent political violence. In many such instances, the resultant quantitative and qualitative overtaxing of law en- forcement capabilities to keep the peace has led to calls by sections of the public, as well as by the legislative and executive branches of government, to expand both the le- gal and operational means available to combat terrorism, and to boost civilian agen- cies’ capacity to deal with terrorism in proportion to the perceived threat. The deterio- rating situation in Ulster in Northern Ireland between 1968 and 1972 and beyond is an illustrative case in point.1 Although there have been cases of successfully transmogrifying police forces into military-like formations, the best-known and arguably most frequent example of aug- mented state responses to the threat posed by insurgent political violence movements is the use of the military in the fight against terrorism and in the maintenance of internal security. While it is imperative that the threat of a collapse of national cohesion due to the overextension of internal civil security forces be averted, the deployment of all branches of the armed forces against a terrorist threat is not without its own pitfalls. Paul Wilkinson has enunciated some of the problems posed by the use of counter-ter- rorism military task forces, not the least of which is that [a] fully militarized response implies the complete suspension of the civilian legal system and its replacement by martial law, summary punishments, the imposition of curfews, military censorship and extensive infringements of normal civil liberties in the name of the exigencies of war. -

Gaza CRISIS)P H C S Ti P P I U

United Nations Office for the Coordination of Humanitarian Affairs occupied Palestinian territory Zikim e Karmiya s n e o il Z P m A g l in a AGCCESSA ANDZ AMOV EMENTSTRI (GAZA CRISIS)P h c s ti P P i u F a ¥ SEPTEMBER 2014 o nA P N .5 F 1 Yad Mordekhai EREZ CROSSING (BEIT HANOUN) occupied Palestinian territory: ID a As-Siafa OPEN, six days (daytime) a B?week4 for B?3the4 movement d Governorates e e of international workers and limited number of y h s a b R authorized Palestinians including aid workers, medical, P r 2 e A humanitarian cases, businessmen and aid workers. Jenin d 1 e 0 Netiv ha-Asara P c 2 P Tubas r Tulkarm r fo e S P Al Attarta Temporary Wastewater P n b Treatment Lagoons Qalqiliya Nablus Erez Crossing E Ghaboon m Hai Al Amal r Fado's 4 e B? (Beit Hanoun) Salfit t e P P v i Al Qaraya al Badawiya i v P! W e s t R n m (Umm An-Naser) n i o » B a n k a North Gaza º Al Jam'ia ¹¹ M E D I TER RAN EAN Hatabiyya Ramallah da Jericho d L N n r n r KJ S E A ee o Beit Lahia D P o o J g Wastewater Ed t Al Salateen Beit Lahiya h 5 Al Kur'a J a 9 P l D n Treatment Plant D D D D 9 ) D s As Sultan D 1 2 El Khamsa D " Sa D e J D D l i D 0 D s i D D 0 D D d D D m 2 9 Abedl Hamaid D D r D D l D D o s D D a t D D c Jerusalem D D c n P a D D c h D D i t D D s e P! D D A u P 0 D D D e D D D a l m d D D o i t D D l i " D D n . -

TRAFFICKING in PERSONS 2020 COUNTRY PROFILE North Africa and the Middle East Table of Contents − Algeria −

GLOBAL REPORT ON TRAFFICKING IN PERSONS 2020 COUNTRY PROFILE North Africa and the Middle East Table of Contents − Algeria − ...................................................................................................................................................... 3 − Bahrain − .................................................................................................................................................... 5 − Egypt − ........................................................................................................................................................ 8 − Iraq − ........................................................................................................................................................ 11 − Israel − ...................................................................................................................................................... 14 − Jordan − .................................................................................................................................................... 17 − The Kingdom of Saudi Arabia − ................................................................................................................ 18 − Kuwait − .................................................................................................................................................... 20 − Lebanon − ................................................................................................................................................ -

Internal Security Forces

Lebanese Republic Ministry of Interior and Municipalities Directorate General of the Internal Security Forces Internal Security Forces Code of Conduct All rights reserved – Directorate General of the Internal Security Forces © 2011. No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system or transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic, mechanical, photocopying, recording or otherwise, without the prior written permission of the Directorate General of the Internal Security Forces. www.isf.gov.lb Foreword by the Minister of Interior and Municipalities From the moment I assumed my responsibilities as Minister of Interior and Municipalities, and throughout my years of military service within the Internal Security Forces (ISF), my foremost concerns were, and continue to be, the enforcement of the law, the maintenance of public order, the reinforcement of security, the preservation of rights and the protection of freedoms. Creating a safe and stable society with decreasing crime rates is dependent on building certain material and ethical pillars. This will reassure the people that they live in an environment where their citizenship is respected, their rights are safeguarded and their dignity is preserved. In a groundbreaking step forward, the Directorate General of the Internal Security Forces is introducing an exhaustive Code of Conduct for its members, laying out their rights and obligations and the way they should interact with the public, authorities, and institutions. This is a pioneering accomplishment and a worthy model for Lebanon and the world as the Code of Conduct establishes institutional, ethical and professional ground rules observing national legislation and international conventions and standards. -

Human Rights and Structure of Police and Internal Security Forces in Uganda Nagujja Zam Zam

Third World Legal Studies Volume 14 The Governance of Internal Security Forces Article 6 in Sub-Saharan Africa 1-6-1997 Human Rights and Structure of Police and Internal Security Forces in Uganda Nagujja Zam Zam Follow this and additional works at: http://scholar.valpo.edu/twls Recommended Citation Zam Zam, Nagujja (1997) "Human Rights and Structure of Police and Internal Security Forces in Uganda," Third World Legal Studies: Vol. 14, Article 6. Available at: http://scholar.valpo.edu/twls/vol14/iss1/6 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by the Valparaiso University Law School at ValpoScholar. It has been accepted for inclusion in Third World Legal Studies by an authorized administrator of ValpoScholar. For more information, please contact a ValpoScholar staff member at [email protected]. HUMAN RIGHTS AND STRUCTURE OF POLICE AND INTERNAL SECURITY FORCES IN UGANDA Nagujja Zam Zam I. BACKGROUND Uganda, like many African countries in the pre-colonial era, was a multiplicity of small kingdoms, chiefdoms and tribal societies. The primary interest of these peoples was subsistence. Criminal justice was maintained by kinship and the ultimate right to seek vengeance through the blood feud. There was a large degree of stability without a central authority, and in the 1870s a rudimentary criminal justice system existed. Punishment of breaches of peace was based on individual action rather than an established authority, except in the kingdoms of Buganda and Bunyoro-Kitara which had a more institutionalised set up. In the Buganda, each kingdom had its "army" for protection and expansion of the kingdom through tribal wars. -

The Internal Security Forces (I.S.F) in Lebanon Their Creation – History- Development

The Internal Security Forces (I.S.F) in Lebanon Their creation – History- Development First : The creation of the I.S.F. Lebanon did not know a police organization, in the modern and legal meaning, before the creation of a lebanese gendarmerie by virtue of protocol 1861. Before this year, the Lebanese Emirs, with the help of their armed men, were in charge of policing, law enforcement and tax-collect. We will present hereunder a summary concerning the creation of the I.S.F. 1- The mandate of Emir Fakhreddine II (He came to power in 1589): The Emir Fakhreddine II is considered to be the founder of the modern Lebanese state. After a perturbated childhood, he came to power in 1589 and started instantly working for the unification of the country, by destroying some independent ephemeral Lebanese families, who were dissenters. In order to control policing and for the execution of ordinary police missions, the Emir has created a group of armed men, named “Zelems” i.e. direct servants. There were also another little groups of “Zelems” for feudal lords. If internal disorders became alarming and threatening the total security of the country, the Emir did not hesitate to ask help from his professional elements “The Sikmans”, who were foreign mercenaries. Nevertheless, he avoided the participation of “Bedouins”, used to theft and murders, instead of military actions. 2- The mandate of Emir Bechir II (He came to power in 1788) There were two kinds of military elements for policing: the first are “Cavaliers” of Emir Bechir the great and “Tax Collector” or “Hawalie” whose functions were as gendarmes, threatening evildoers. -

Saudi Internal Security: a Risk Assessment

CSIS_______________________________ Center for Strategic and International Studies 1800 K Street N.W. Washington, DC 20006 (202) 775-3270 Access: Web: CSIS.ORG Contact the Author: [email protected] & [email protected] Saudi Internal Security: A Risk Assessment Terrorism and the Security Services- Challenges & Developments Anthony H. Cordesman and Nawaf Obaid Center for Strategic and International Studies Working Draft: May 30, 2004 Please note that this document is a working draft and will be revised regularly as part of the CSIS Saudi Arabia Enters the 21st Century Project. It is also being used by the authors to develop an analysis for the Geneva Center on Security Policy. To comment, or to provide suggestions and corrections to the authors, please e-mail them at [email protected], [email protected] and [email protected]. Cordesman: The Security Apparatus in Saudi Arabia 6/1/04 Page ii INTRODUCTION .......................................................................................................................................................... 1 THE SAUDI SECURITY APPARATUS ...................................................................................................................... 2 THE LEADERSHIP OF THE SAUDI SECURITY APPARATUS ............................................................................ 2 THE IMPORTANCE OF CONSENSUS AND CONSULTATION ............................................................................ 3 THE SAUDI PARAMILITARY AND INTERNAL SECURITY APPARATUS ..................................................... -

Weekly Report on Israeli Human Rights Violations in the Occupied Palestinian Territory (10 – 16 November 2016) | Palestinian Center for Human Rights

11/17/2016 Weekly Report On Israeli Human Rights Violations in the Occupied Palestinian Territory (10 – 16 November 2016) | Palestinian Center for Human Rights Weekly Report On Israeli Human Rights Violations in the Occupied Palestinian Territory (10 – 16 November 2016) Israeli forces continue systematic crimes in the occupied Palestinian territory (oPt) (10 – 16 November 2016) Israeli forces continued to use excessive force in the oPt 6 Palestinian civilians, including 2 children, were wounded in the West Bank and Gaza Strip. House demolitions on grounds of collective punishment. A room was closed with concrete in Yatta, south of Hebron. Israeli forces conducted 64 incursions into Palestinian communities in the West Bank and 6 ones in occupied Jerusalem. 57 civilians, including 15 children and a woman, were arrested. Fifteen of them, including 12 children and the woman, were arrested in occupied Jerusalem. The Health Improvement Program’s office in Ramallah was raided and some of its content were confiscated. Israeli forces continued to target Palestinian fishermen in the Gaza Strip Sea. 2 fishermen were arrested and their fishing boat was confiscated, north of the Gaza Strip. Israeli forces continued their efforts to create Jewish majority in occupied East Jerusalem. 2 residential apartments in alMukaber Mount and 2 stores in Beit Hanina were selfdemolished by their owners. 2 barracks, an agricultural room and a mosque foundation in Silwan and Sour Baher villages were demolished. Settlement activities continued in the West Bank. 2 agricultural rooms in Qalqilya and a residential tent, a social service centre and a well, south of Hebron, were demolished. -

Urban Planning Analyses of Refugee Camps, Jabalia As Case Study-Gaza Strip, Palestine

International Journal of Science and Research (IJSR) ISSN (Online): 2319-7064 Index Copernicus Value (2013): 6.14 | Impact Factor (2015): 6.391 Urban Planning Analyses of Refugee Camps, Jabalia as Case Study-Gaza Strip, Palestine Dr. Usama Ibrahim Badawy1, Dr Ra’ed A. Salha2, Dr. Muain Qasem Jawabrah3, Amjad Jarada4 Mohammed A. EL Hawajri5 1Former Professor of Architecture, Birzeit University Palestine, works currently at UNRWA 2Assistant Professor, Islamic University of Gaza in Geography and GIS Palestine 3Assistance Professor, Architecture Department, Birzeit University Palestine 4Researcher in Infrastructure Planning and Development works currently at UNRWA, G, 5Researcher Geography subjects, works currently as teacher by the Ministry of Education Abstract: The Gaza Strip is a tight area with more than 1.8 million inhabitants. Since the beginning of the last century, and as other Palestinian areas, Gaza Strip was subject to direct occupation. The occupation tightened laws and regulations and increased obstacles, meanwhile it established settlements in a method that besieges existing Palestinian urban areas and leads them to develop in a way that serves the occupation, particularly the security side. This research begins with background information on Palestinian refugees in Gaza, sees that camp Improvement Strategies should called for adoption of the future urban planning, increasing the accommodation capacity of the built-up area, activating the environmental resources protection laws and played down the issue of the land properties when preparing the comprehensive plans. In this study reviews options for addressing the problems faced by Palestinian refugees in Gaza, Recommendations: After discussing the topic through a analyses of the Current Conditions , Land availability, Population distribution, Land requirements, Overcrowding, Public Spaces problems inside the camps , Sustainability in Gaza Strip, socio-economic situation , Unemployment problem and Population density in Jabalia Camp.