University of Cincinnati

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Urban Planning Analyses of Refugee Camps, Jabalia As Case Study-Gaza Strip, Palestine

International Journal of Science and Research (IJSR) ISSN (Online): 2319-7064 Index Copernicus Value (2013): 6.14 | Impact Factor (2015): 6.391 Urban Planning Analyses of Refugee Camps, Jabalia as Case Study-Gaza Strip, Palestine Dr. Usama Ibrahim Badawy1, Dr Ra’ed A. Salha2, Dr. Muain Qasem Jawabrah3, Amjad Jarada4 Mohammed A. EL Hawajri5 1Former Professor of Architecture, Birzeit University Palestine, works currently at UNRWA 2Assistant Professor, Islamic University of Gaza in Geography and GIS Palestine 3Assistance Professor, Architecture Department, Birzeit University Palestine 4Researcher in Infrastructure Planning and Development works currently at UNRWA, G, 5Researcher Geography subjects, works currently as teacher by the Ministry of Education Abstract: The Gaza Strip is a tight area with more than 1.8 million inhabitants. Since the beginning of the last century, and as other Palestinian areas, Gaza Strip was subject to direct occupation. The occupation tightened laws and regulations and increased obstacles, meanwhile it established settlements in a method that besieges existing Palestinian urban areas and leads them to develop in a way that serves the occupation, particularly the security side. This research begins with background information on Palestinian refugees in Gaza, sees that camp Improvement Strategies should called for adoption of the future urban planning, increasing the accommodation capacity of the built-up area, activating the environmental resources protection laws and played down the issue of the land properties when preparing the comprehensive plans. In this study reviews options for addressing the problems faced by Palestinian refugees in Gaza, Recommendations: After discussing the topic through a analyses of the Current Conditions , Land availability, Population distribution, Land requirements, Overcrowding, Public Spaces problems inside the camps , Sustainability in Gaza Strip, socio-economic situation , Unemployment problem and Population density in Jabalia Camp. -

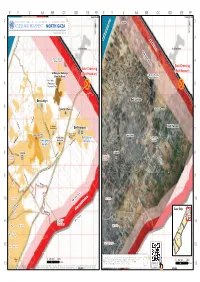

North Gaza ¥ August 2011 ¥ 3 3 Mediterranean Sea No-Go Zone

No Fishing Zone 1.5 nautical miles 3 nautical miles X Y Z AA BB CC DD EE FF X Y Z AA BB CC DD EE FF Yad Mordekhai Yad Mordekhai 2 United Nations OfficeAs-Siafa for the Coordination of Humanitarian Affairs As-Siafa 2 ACCESS AND MOVEMENT - NORTH GAZA ¥ auGUST 2011 ¥ 3 3 Mediterranean Sea No-Go Zone Al-Rasheed Netiv ha-Asara Netiv ha-Asara High Risk Zone Temporary Wastewater 4 Treatment Lagoons 4 Erez Crossing Erez Crossing Al Qaraya al Badawiya (Beit Hanoun) (Beit Hanoun) Al Qaraya al Badawiya (Umm An-Naser) (Umm An-Naser) Beit Lahia 5 Wastewater 5 Treatment Plant Beit Lahiya Beit Lahiya 6 6 'Izbat Beit Hanoun 'Izbat Beit Hanoun Al Mathaf Hotel Al-Sekka Al Karama Al Karama El-Bahar Beit Lahia Main St. Arc-Med Hotel Al-Faloja Sheikh Zayed Beit Hanoun Housing Project Beit Hanoun Madinat al 'Awda 7 v®Madinat al 'Awda 7 Beit Hanoun Jabalia Camp v® Industrial Jabalia Camp 'Arab Maslakh Zone Beit Hanoun 'Arab Maslakh Kamal Edwan Beit Lahya Beit Lahya Abu Ali Eyad Kamal Edwan Hospital Al-Naser Al-Saftawi Hospital Khalil Al-Wazeer Ahmad Sadeq Ash Shati' Camp Said El-Asi Jabalia Jabalia An Naser 8 Al-quds An Naser 8 El-Majadla Ash Sheikh Yousef El-Adama Ash Sheikh Al-Sekka Radwan Radwan Falastin Khalil El-Wazeer Al Deira Hotel Ameen El Husaini Heteen Salah El-Deen ! Al-Yarmook Saleh Dardona Abu Baker Al-Razy Palestine Stadium Al-Shifa Al-Jalaa 9 9 Hospital ! Al-quds Northern Rimal Al-Naffaq Al-Mashahra El-Karama Northern Rimal Omar El-Mokhtar Southern Rimal Al-Wehda Al-Shohada Al Azhar University Ad Daraj G Ad Daraj o v At Tuffah e At Tuffah 10 r 10 n High Risk Zone Islamic ! or Al-Qanal a University Yafa t e Haifa Jamal Abdel Naser Al-Sekka 500 meter NO-Go Zone Salah El-Deen Gaza Strip Beit Lahiya Al-Qahera Khalil Al-Wazeer J" Boundar J" y JabalyaJ" Al-Aqsa As Sabra Gaza City Beit Hanun Gaza City Marzouq GazaJ" City Northern Gaza Al-Dahshan Wire Fence Al 'Umari11 Wastewater 11 Mosque Moshtaha Treatment Plant Tal El Hawa Ijdeedeh Ijdeedeh Deir alJ" Balah Old City Bagdad Old City Rd No. -

Gaza CRISIS)P H C S Ti P P I U

United Nations Office for the Coordination of Humanitarian Affairs occupied Palestinian territory Zikim e Karmiya s n e o il Z P m A g l in a AGCCESSA ANDZ AMOV EMENTSTRI (GAZA CRISIS)P h c s ti P P i u F a ¥ SEPTEMBER 2014 o nA P N .5 F 1 Yad Mordekhai EREZ CROSSING (BEIT HANOUN) occupied Palestinian territory: ID a As-Siafa OPEN, six days (daytime) a B?week4 for B?3the4 movement d Governorates e e of international workers and limited number of y h s a b R authorized Palestinians including aid workers, medical, P r 2 e A humanitarian cases, businessmen and aid workers. Jenin d 1 e 0 Netiv ha-Asara P c 2 P Tubas r Tulkarm r fo e S P Al Attarta Temporary Wastewater P n b Treatment Lagoons Qalqiliya Nablus Erez Crossing E Ghaboon m Hai Al Amal r Fado's 4 e B? (Beit Hanoun) Salfit t e P P v i Al Qaraya al Badawiya i v P! W e s t R n m (Umm An-Naser) n i o » B a n k a North Gaza º Al Jam'ia ¹¹ M E D I TER RAN EAN Hatabiyya Ramallah da Jericho d L N n r n r KJ S E A ee o Beit Lahia D P o o J g Wastewater Ed t Al Salateen Beit Lahiya h 5 Al Kur'a J a 9 P l D n Treatment Plant D D D D 9 ) D s As Sultan D 1 2 El Khamsa D " Sa D e J D D l i D 0 D s i D D 0 D D d D D m 2 9 Abedl Hamaid D D r D D l D D o s D D a t D D c Jerusalem D D c n P a D D c h D D i t D D s e P! D D A u P 0 D D D e D D D a l m d D D o i t D D l i " D D n . -

Gaza Strip Closure Map , December 2007

UN Office for the Coordination of Humanitarian Affairs Access and Closure - Gaza Strip December 2007 s rd t: o i t c im n N c L e o Erez A . m F g m t i lo n . i s s i n m h Crossing Point h t: in O s 0 m i s g i 2 o le F im i A Primary crossing for people (workers C L m re i l a and traders) and humanitarian personnel in g a rt in c Closed for Palestinian workers e h ti s u since 12 March 2006 B i a 2 F Closed for Palestinians 0 n 0 2 since 12 June 2007 except for a limited 2 1 number of traders, humanitarian workers and medical cases s F le D i I m y l B a d ic e t c u r a Al Qaraya al Badawiya al Maslakh ¯p fo n P Ç 6 n : ¬ E 6 it 0 Beit Lahiya 0 im 2 P L r Madinat al 'Awda e P ¯p "p ¯p "p g b Beit Hanoun in o ¯p ¯p ¯p ¯p h t Jabalia Camp ¯p ¯p ¯p P ¯p s c p ¯p ¯p i p"p ¯¯p "pP 'Izbat Beit HanounP F O Ash Shati' Camp ¯p " ¯p e "p "p ¯p ¯p c Gaza ¯Pp ¯p "p n p i t ¯ Wharf S Jabalia S t !x id ¯p S h s a a "p m R ¯p¯p¯p ¯p a l- ¯p p r A ¯p ¯ a "p K "p ¯p l- ¯p "p E ¯p"p ¯p¯p"p ¯p¯p ¯p Gaza ¯p ¯p ¯p ¯p t S ¯p a m ¯p¯p ¯p ra a K l- Ç A ¬ Nahal Oz ¯p ¬Ç Crossing point for solid and liquid fuels p t ¯ t S fa ¯p Al Mughraqa (Abu Middein) ra P r A e as Y Juhor ad Dik ¯pP ¯p LEBANON An Nuseirat Camp ¯p ¯p West Bank and Gaza Strip P¯p ¯p ¯p West Bank Barrier (constructed and planned) ¯p ¯p ¯p Al Bureij Camp¯p ¯p Karni Areas inaccessible to Palestinians or subject to restrictions ¯p¯pP¯p Crossing `Akko !P MEDITERRANEAN Az Zawayda !P Deir al Balah ¯p P Point SEA Haifa Tiberias !P Wharf Nazareth !P ¯p Al Maghazi Camp¯p¯p Deir al Balah Camp Primary -

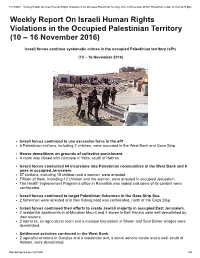

Weekly Report on Israeli Human Rights Violations in the Occupied Palestinian Territory (10 – 16 November 2016) | Palestinian Center for Human Rights

11/17/2016 Weekly Report On Israeli Human Rights Violations in the Occupied Palestinian Territory (10 – 16 November 2016) | Palestinian Center for Human Rights Weekly Report On Israeli Human Rights Violations in the Occupied Palestinian Territory (10 – 16 November 2016) Israeli forces continue systematic crimes in the occupied Palestinian territory (oPt) (10 – 16 November 2016) Israeli forces continued to use excessive force in the oPt 6 Palestinian civilians, including 2 children, were wounded in the West Bank and Gaza Strip. House demolitions on grounds of collective punishment. A room was closed with concrete in Yatta, south of Hebron. Israeli forces conducted 64 incursions into Palestinian communities in the West Bank and 6 ones in occupied Jerusalem. 57 civilians, including 15 children and a woman, were arrested. Fifteen of them, including 12 children and the woman, were arrested in occupied Jerusalem. The Health Improvement Program’s office in Ramallah was raided and some of its content were confiscated. Israeli forces continued to target Palestinian fishermen in the Gaza Strip Sea. 2 fishermen were arrested and their fishing boat was confiscated, north of the Gaza Strip. Israeli forces continued their efforts to create Jewish majority in occupied East Jerusalem. 2 residential apartments in alMukaber Mount and 2 stores in Beit Hanina were selfdemolished by their owners. 2 barracks, an agricultural room and a mosque foundation in Silwan and Sour Baher villages were demolished. Settlement activities continued in the West Bank. 2 agricultural rooms in Qalqilya and a residential tent, a social service centre and a well, south of Hebron, were demolished. -

Urban Planning Analyses of Refugee Camps, Jabalia As Case Study-Gaza Strip, Palestine

International Journal of Science and Research (IJSR) ISSN (Online): 2319-7064 Index Copernicus Value (2013): 6.14 | Impact Factor (2015): 6.391 Urban Planning Analyses of Refugee Camps, Jabalia as Case Study-Gaza Strip, Palestine Dr. Usama Ibrahim Badawy1, Dr Ra’ed A. Salha2, Dr. Muain Qasem Jawabrah3, Amjad Jarada4 Mohammed A. EL Hawajri5 1Former Professor of Architecture, Birzeit University Palestine, works currently at UNRWA 2Assistant Professor, Islamic University of Gaza in Geography and GIS Palestine 3Assistance Professor, Architecture Department, Birzeit University Palestine 4Researcher in Infrastructure Planning and Development works currently at UNRWA, G, 5Researcher Geography subjects, works currently as teacher by the Ministry of Education Abstract: The Gaza Strip is a tight area with more than 1.8 million inhabitants. Since the beginning of the last century, and as other Palestinian areas, Gaza Strip was subject to direct occupation. The occupation tightened laws and regulations and increased obstacles, meanwhile it established settlements in a method that besieges existing Palestinian urban areas and leads them to develop in a way that serves the occupation, particularly the security side. This research begins with background information on Palestinian refugees in Gaza, sees that camp Improvement Strategies should called for adoption of the future urban planning, increasing the accommodation capacity of the built-up area, activating the environmental resources protection laws and played down the issue of the land properties when preparing the comprehensive plans. In this study reviews options for addressing the problems faced by Palestinian refugees in Gaza, Recommendations: After discussing the topic through a analyses of the Current Conditions , Land availability, Population distribution, Land requirements, Overcrowding, Public Spaces problems inside the camps , Sustainability in Gaza Strip, socio-economic situation , Unemployment problem and Population density in Jabalia Camp. -

Security Council Ic

UNITED NATIONS Security Council Distr. Ic GENERAL s/14930 26 March 1982 ORIGINAL: ENGLISH LETTER DATED 25 MARCH 1982 FROM THE PERMANENT REPRESENTATIVE OF JORDAN TO THE UNITED NATIONS ADDRESSED TO THE PRESIDENT OF THE SECURITY COUNCIL I have the honour to forward to you the enclosed letter, at the request of Mr. zuhdi Labib Terzi, the Permanent Cbserver of the Palestine Liberation Organization, concerning further acts of brutality against the Mayor of Nablus, Mr. Bassam Shakaa and the Mayor of Ramallah, Mr. Kaeim Khalef, who were arrested and removed from their legally elected offices. Inasmuch as these acts of terror and brutality continue to pervade the occupied Palestinian territory, I would deeply appreciate it if my letter and the enclosed letter from the Permanent Observer of the Palestine Liberation Organization could be circulated as a document of the Security Council. (Signed) Hazem NUSEIBEH Ambassador Permanent Representative 82-07682 0300~ (E) / ,.. s/14930 hglish Annex Page 1 ---Annex Ix'cter dated 25 March 1982 from the Permanent Observer of the' Palestine Liberation Organization to the Uhited Nations addressed to the President of the Security Council I am requested by Chairman Yasser Arafat to bring the following to your most urgent attention. ?bday Mayor Bassam Shakaa of Nablus and Mayor Karim Khalef of Ramallah were arrested and removed from their legally elected offices. Israeli troops then installed so-called civilian administrators in their place. Speculation is 'chat the arrests of Shakaa and Khalef precede their forceable deportation and exile from Palestine. Members of the Nablus municipality and a number of Shakaa's supporters were summoned to General Menahem Milson's office and threatened with severe repercussions should they allow the situation in Nablus to deteriorate. -

(^Ш/ World Health Organization ^^^^ Organisation Mondiale De La Santé

(^Ш/ World Health Organization ^^^^ Organisation mondiale de la Santé FORTY-SEVENTH WORLD HEALTH ASSEMBLY Provisional agenda item 32 A47/INF.DOC./3 2 May 1994 Health conditions of the Arab population in the occupied Arab territories, including Palestine The Director-General has the honour to bring to the attention of the Health Assembly the attached annual report of the Director of Health of the United Nations Relief and Works Agency for Palestine Refugees in the Near East (UNRWA) for the year 1993. HEALTH CONDITIONS OF THE ARAB POPULATION IN THE OCCUPIED ARAB TERRITORIES, INCLUDING PALESTINE Report of the UNRWA Department of Health, 1993 CONTENTS Page I. INTRODUCTION 2 II. UNRWA'S HEALTH PROGRAMME 2 III. HEALTH STATUS OF PALESTINE REFUGEES 3 IV. PROGRAMME ACTIVITIES DURING 1993 5 Medical Care Services 5 Maternal and Child Health Care 5 Mental Health 6 Environmental Health 6 V. SITUATION IN THE OCCUPIED TERRITORY 8 VI. UNRWA'S CONTRIBUTION TO HEALTH SECTOR DEVELOPMENT 8 VII. UNRWA'S ROLE DURING THE TRANSITION PERIOD 10 STATISTICAL ANNEX 13 I. INTRODUCTION 1. The Annual Report of the Department of Health of UNRWA for 1993 covers a year in which historic events have taken place that will create a radically different situation in the Agency's area of operations. 2. The Palestine Liberation Organization and the Government of Israel have recognized each other and signed a Declaration of Principles, which is guiding their negotiations for an interim self-government period in the Gaza Strip and West Bank. 3. There is no doubt that these momentous developments have already had a great impact on the perceptions of all parties concerned as well as on UNRWA's role under the new conditions. -

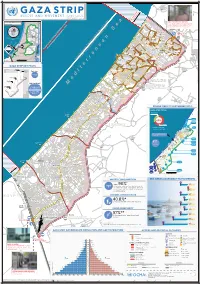

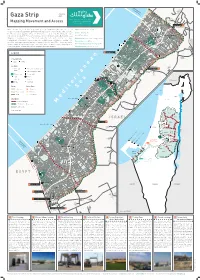

Gaza Strip 2020 As-Siafa Mapping Movement and Access Netiv Ha'asara Temporary

Zikim Karmiya No Fishing Zone 1.5 nautical miles Yad Mordekhai January Gaza Strip 2020 As-Siafa Mapping Movement and Access Netiv Ha'asara Temporary Ar-Rasheed Wastewater Treatment Lagoons Sources: OCHA, Palestinian Central Bureau of Statistics of Statistics Bureau Central OCHA, Palestinian Sources: Erez Crossing 1 Al-Qarya Beit Hanoun Al-Badawiya (Umm An-Naser) Erez What is known today as the Gaza Strip, originally a region in Mandatory Palestine, was created Width 5.7-12.5 km / 3.5 – 7.7 mi through the armistice agreements between Israel and Egypt in 1949. From that time until 1967, North Gaza Length ~40 km / 24.8 mi Al- Karama As-Sekka the Strip was under Egyptian control, cut off from Israel as well as the West Bank, which was Izbat Beit Hanoun al-Jaker Road Area 365 km2 / 141 m2 Beit Hanoun under Jordanian rule. In 1967, the connection was renewed when both the West Bank and the Gaza Madinat Beit Lahia Al-'Awda Strip were occupied by Israel. The 1993 Oslo Accords define Gaza and the West Bank as a single Sheikh Zayed Beit Hanoun Population 1,943,398 • 48% Under age 17 July 2019 Industrial Zone Ash-Shati Housing Project Jabalia Sderot territorial unit within which freedom of movement would be permitted. However, starting in the camp al-Wazeer Unemployment rate 47% 2019 Q2 Jabalia Camp Khalil early 90s, Israel began a gradual process of closing off the Strip; since 2007, it has enforced a full Ash-Sheikh closure, forbidding exit and entry except in rare cases. Israel continues to control many aspects of Percentage of population receiving aid 80% An-Naser Radwan Salah Ad-Deen 2 life in Gaza, most of its land crossings, its territorial waters and airspace. -

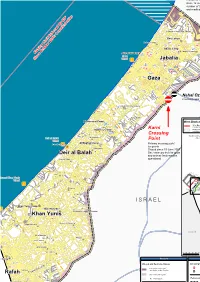

GAZA Situation Map - As of 5Th of January 2009

GAZA Situation Map - as of 5th of January 2009 Reported Palestinian casualties as of 5 January 2009 * Killed 534 20% of killed Palestinians Siafa are civilians Injured Erez crossing point is partially open 2,470 Al Qaraya al Badawiya for a limited number of medical al Maslakh evacuations and foreign nationals. Madinat al 'Aw da Beit Lahiya * Beit Hanoun Situation Jabalia Camp Ash Shati' Camp • More than a million Gazans still have 'Izbat Beit Hanoun no electricity or water, and thousands Gaza Jabalia = 25 people = 25 people of people have fled their homes for safe Wharf shelter. Based on MoH as of 5 January 2009 40% of injured Palestinians are civilians * 'A rab Maslakh Beit Lahiya • Hospitals are unable to provide adequate Reported Israeli casualties as of 5 January 2009 Gaza intensive care to the high number of Killed * casualties. 8 of which 4 are civilians crossing point for fuels - open today. dead and at least injured Injured Nahal Oz • 534 2470 of which 46 are civilians 215,000 litres of industrial fuel along with 47 tonnes since 27 December, Source: Palestinian 106 of cooking gas have been pumped from Israel to Gaza Ministry of Health MoH, as of 5th of = 25 people January 2009. = 25 people Al Zahra Al Mughraqa Karni crossing * Based on the Israeli Magen David Adom and the Israeli (Abu Middein) Defence Force (IDF), as of 5 January point for goods • 60 IDF soldiers have been wounded in Gaza since Saturday the 4th of Jan., Priority Needs: including four who remain in serious condition. • Industrial fuel is needed to power the Gaza Power Plant. -

REFUGEE CAMPS in the West Bank We Provide Services in 19 Palestine Refugee Camps in the West Bank

PALESTINIAN REFUGEES IN WEST BANK & GAZA STRIP https://www.unrwa.org/palestine-refugees Nearly one-third of the registered Palestine refugees, more than 1.5 million individuals, live in 58 recognized Palestine refugee camps in Jordan, Lebanon, the Syrian Arab Republic, the Gaza Strip and the West Bank, including East Jerusalem. Palestine refugees are defined as “persons whose normal place of residence was Palestine during the period 1 June 1946 to 15 May 1948, and who lost both home and means of livelihood as a result of the 1948 conflict.” UNRWA services are available to all those living in its area of operations who meet this definition, who are registered with the Agency and who need assistance. The descendants of Palestine refugee males, including adopted children, are also eligible for registration. When the Agency began operations in 1950, it was responding to the needs of about 750,000 Palestine refugees. Today, some 5 million Palestine refugees are eligible for UNRWA services. A Palestine refugee camp is defined as a plot of land placed at the disposal of UNRWA by the host government to accommodate Palestine refugees and set up facilities to cater to their needs. Areas not designated as such and are not recognized as camps. However, UNRWA also maintains schools, health centres and distribution centres in areas outside the recognized camps where Palestine refugees are concentrated, such as Yarmouk, near Damascus. WEST BANK: (31 dec 2016) https://www.unrwa.org/where-we-work/west-bank Facts & figures : 809,738 registered Palestine refugees 19 camps 96 schools, with 48,956 pupils 2 vocational and technical training centres 43 primary health centres 15 community rehabilitation centres 19 women’s programme centres REFUGEE CAMPS IN the West Bank We provide services in 19 Palestine refugee camps in the West Bank. -

Palestinian Security Sector Governance

Palestinian Security Sector Governance Challenges and Prospects Palestinian Academic Society for the Study of International Affairs, Jerusalem (PASSIA) Geneva Centre for the Democratic Control of Armed Forces (DCAF) August 2006 Copyright © PASSIA – DCAF, 2006 P.O. Box 19545, Jerusalem Tel.: (02)626 4426 Fax: (02)628 2819 E-mail: [email protected] Website: www.passia.org P.O. Box 1360, CH-1211 Geneva 1, Switzerland Tel.: +41 (22) 741 77 00 Fax: +41 (22) 741 77 05 Website: www.dcaf.ch The Palestinian Academic Society for the Study of International Affairs (PASSIA) is an independent Palestinian non-profit institution, not affiliated with any government, political party or organization. PASSIA seeks to present the Palestine Question in its national, regional and international contexts through academic research, dialogue and publication. PASSIA endeavours that research undertaken under its auspices be specialized and scientific and that its symposia and workshops, whether international or intra-Palestinian, be open, self- critical and conducted in a spirit of cooperation. The Geneva Centre for the Democratic Control of Armed Forces (DCAF) promotes good governance and reform of the security sector. The Centre conducts research on good practices, encourages the development of appropriate norms at the national and international levels, makes policy recommendations and provides in-country advice and assistance programmes. DCAF’s partners include governments, parliaments, civil society, and international organizations. Disclaimer The views presented in this book are personal, i.e., that of the authors, and do not necessarily represent the views of PASSIA or DCAF. The publication of this book was kindly supported by the Geneva Centre for Democratic Control of Armed Forces (DCAF).