Palestine Case Study

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

COVID-19 and Gender Justice: FEMINISTS in MENA DEFYING GLOBAL STRUCTURAL FAILURE COVID-19 and GENDER JUSTICE: FEMINISTS in MENA DEFYING GLOBAL STRUCTURAL FAILURE

COVID-19 and Gender Justice: FEMINISTS IN MENA DEFYING GLOBAL STRUCTURAL FAILURE COVID-19 AND GENDER JUSTICE: FEMINISTS IN MENA DEFYING GLOBAL STRUCTURAL FAILURE ©2020 Women’s International League for Peace and Freedom Permission is granted for non-commercial reproduction, copying, distribution, and transmission of this publication or parts thereof so long as full credit is given to the publishing organisation; the text is not altered, transformed, or built upon; and for any reuse or distribution, these terms are made clear to others. COVID-19 and Gender Justice: Feminists in MENA Defying Global Structural Failure July 2020 24 pp. Author: Rola Al Masri Design: Nadia Joubert Cover photo credit: Nadia Joubert For more information, contact: Women’s International League for Peace and Freedom (WILPF) Rue de Varembé 1, Zip code 28, 1211 Geneva 20, Switzerland [email protected] | +41 (0)22 919 70 80 | wilpf.org COVID-19 AND GENDER JUSTICE: FEMINISTS IN MENA DEFYING GLOBAL STRUCTURAL FAILURE Table of Contents Introduction 2 Structural Failure in the Official Response to the COVID-19 Outbreak 3 Exploring the Root Causes of COVID-19 Response Failure 4 The United Nations’ Response to COVID-19: Inadequate and at Times Biased 11 Impact of COVID-19 on Women and Feminist Agendas and Organisations in MENA 12 Concluding Remarks 19 Recommendations 19 Acknowledgements 21 – 1 – COVID-19 AND GENDER JUSTICE: FEMINISTS IN MENA DEFYING GLOBAL STRUCTURAL FAILURE Introduction The COVID-19 pandemic has highlighted and exacerbated existing economic, humanitarian and political failures across countries in the MENA (Middle East and North Africa) region and has deepened the multiple crises that continue to threaten peace, human security and justice. -

Organizations of Women: Towards an Equal Future in Palestine

California State University, San Bernardino CSUSB ScholarWorks Electronic Theses, Projects, and Dissertations Office of aduateGr Studies 6-2015 Organizations of Women: Towards an Equal Future in Palestine Beatrice S. Longshore-Cook California State University - San Bernardino Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarworks.lib.csusb.edu/etd Part of the Human Geography Commons, Near and Middle Eastern Studies Commons, and the Social and Cultural Anthropology Commons Recommended Citation Longshore-Cook, Beatrice S., "Organizations of Women: Towards an Equal Future in Palestine" (2015). Electronic Theses, Projects, and Dissertations. 196. https://scholarworks.lib.csusb.edu/etd/196 This Thesis is brought to you for free and open access by the Office of aduateGr Studies at CSUSB ScholarWorks. It has been accepted for inclusion in Electronic Theses, Projects, and Dissertations by an authorized administrator of CSUSB ScholarWorks. For more information, please contact [email protected]. ORGANIZATIONS OF WOMEN: TOWARDS AN EQUAL FUTURE IN PALESTINE A Thesis Presented to the Faculty of California State University, San Bernardino In Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree Master of Arts in Social Sciences by Beatrice Longshore-Cook June 2015 ORGANIZATIONS OF WOMEN: TOWARDS AN EQUAL FUTURE IN PALESTINE A Thesis Presented to the Faculty of California State University, San Bernardino by Beatrice Longshore-Cook June 2015 Approved by: Kevin Grisham, Committee Chair, Geography Teresa Velásquez, Committee Member © 2015 Beatrice Longshore-Cook ABSTRACT The development and struggle for nationalism in Palestine, as seen through an historical lens of the Israeli-Palestinian conflict, demonstrates the complexity of gendered spaces and narratives inherent in any conflict. Women’s roles have often been confined to specific, gendered spaces within their society. -

Jerusalem's Women

Jerusalem’s Women The Growth and Development of Palestinian Women’s movement in Jerusalem during the British Mandate period (1920s-1940s) Nadia Harhash Table of Contents Jerusalem’s Women 1 Nadia Harhash 1 Abstract 5 Appreciations 7 Abbreviations 8 Part One : Research Methodological Outline 9 I Problem Statement and Objectives 10 II Research Tools and Methodology 15 III Boundaries and Limitations 19 IV Literature Review 27 Part Two : The Growth and Development of the Palestinian Women’s Movement in Jerusalem During the British Mandate (1920s-1940s) 33 1 Introduction 34 2 The Photo 41 4 An Overview of the Political Context 47 5 Women Education and Professional Development 53 6 The Emergence of Charitable Societies and Rise of Women Movement 65 7 Rise of Women’s Movement 69 8 Women’s Writers and their contribution 93 9 Biographical Appendix of Women Activists 107 10 Conclusion 135 11 Bibliography 145 Annexes 152 III Photos 153 Documents 154 (Endnotes) 155 ||||| Jerusalem’s Women ||||| Abstract The research discusses the development of the women’s movement in Palestine in the early British Mandate period through a photo that was taken in 1945 in Jerusalem during a meeting of women activists from Palestine with the renowned Egyptian feminist Huda Sha’rawi. The photo sheds light on the side of Palestinian society that hasn’t been well explored or realized by today’s Palestinians. It shows women in a different role than a constructed “traditional” or “authentic” one. The photo gives insights into a particular constituency of the Palestinian women’s movement: urban, secular-modernity women activists from the upper echelons of Palestinian society of the time, women without veils, contributing to certain political and social movements that shaped Palestinian life at the time and connected with other Arab women activists. -

University of Cincinnati

U UNIVERSITY OF CINCINNATI Date: 05-20-2009 I, Shadi Y. Saleh , hereby submit this original work as part of the requirements for the degree of: Master in Architecture It is entitled: Designing by Community Participation: Meeting the Challenges of the Palestinian Refugee Camps Shadi Saleh Student Signature: This work and its defense approved by: Committee Chair: Elizabeth Riorden Thomas Bible Approval of the electronic document: I have reviewed the Thesis/Dissertation in its final electronic format and certify that it is an accurate copy of the document reviewed and approved by the committee. Committee Chair signature: Elizabeth Riorden Designing by Community Participation: Meeting the Challenges of the Palestinian Refugee Camps A thesis submitted to the Division of Research and Advance Studies of the University of Cincinnati in partial fulfillment of the requirements of the degree of Master of Architecture In the school of Architecture and Interior design Of the College of Design, Architecture, Art and Planning 2009 By Shadi Y. Saleh Committee chair Elizabeth Riorden Thomas Bible ABSTRACT Palestinian refugee camps in the West Bank, Gaza Strip, Jordan, Lebanon and Syria are the result of the sudden population displacements of 1948 and 1967. After 60 years, unorganized urban growth compounds the situation. The absence of state support pushed the refugees to take matters into their own hands. Currently the camps have problems stemming from both the social situation and the degradation of the built environment. Keeping the refugee camps in order to “represent” a nation in exile does not mean to me that there should be no development. The thesis seeks to make a contribution in solving the social and environmental problems in a way that emphasizes the Right of Return. -

The Political Participation of Palestinian Women in Official and Non-Official Organizations in Limited Horizon

The Political Participation of Palestinian Women in Official and Non-Official Organizations in Limited Horizon Dima Samaroo THE KING’S PROGRAMME FOR MIDDLE EAST DIALOGUE Every academic year ICSR is offering six young leaders from Israel and Palestine the opportunity to come to London for a period of two months in order to develop their ideas on how to further mutual understanding in their region through addressing both themselves and “the other”, as well as engaging in research, debate and constructive dialogue in a neutral academic environment. The end result is a short paper that will provide a deeper understanding and a new perspective on a specific topic or event that is personal to each Fellow. The views expressed here are solely those of the author and do not reflect those of the International Centre for the Study of Radicalisation. Editor: Katie Rothman, ICSR Dima Samaro earned a Bachelor’s of Law from the University of An-Najah, Palestine. She has been working as a legal researcher for around six months at International Commission of Jurists in Tunisia, which collaborates with organizations such as UN, Amnesty International, Human Rights Watch, and EuroMed Rights, among others. Before this Dima was working for non-profits. Dima has been part of Zimam as a youth trainer advocating for civil peace and social justice in Palestine; running several campaigns, trainings, and activities that aim to raise awareness toward Middle-East peace process, and the challenges that the Palestinian nowadays faces. Dima is a MENA Leadership Academy fellow, Solutions Not Sides program fellow, a winner of “Best Human Rights Report for Impact” awarded by Al-Haq in 2014, and the Goi Peace Foundation awarded her an Honorable Mention of 2016 International Essay Contest for Young People. -

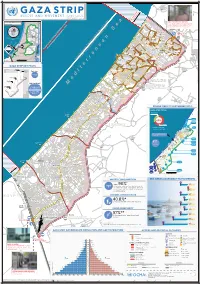

Palestinian Territories MIDDLE EAST UNITARY COUNTRY and WEST ASIA

Palestinian territories MIDDLE EAST UNITARY COUNTRY AND WEST ASIA Basic socio-economic indicators Income group - LOWER MIDDLE INCOME Local currency - Israeli new shekel (ILS) Population and geography Economic data AREA: 6 020 km2 GDP: 19.4 billion (current PPP international dollars) i.e. 4 509 dollars per inhabitant (2014) POPULATION: million inhabitants (2014), an increase 4.295 REAL GDP GROWTH: -1.5% (2014 vs 2013) of 3% per year (2010-2014) UNEMPLOYMENT RATE: 26.9% (2014) 2 DENSITY: 713 inhabitants/km FOREIGN DIRECT INVESTMENT, NET INFLOWS (FDI): 127 (BoP, current USD millions, 2014) URBAN POPULATION: 75.3% of national population GROSS FIXED CAPITAL FORMATION (GFCF): 18.6% of GDP (2014) CAPITAL CITY: Ramallah (2% of national population) HUMAN DEVELOPMENT INDEX: 0.677 (medium), rank 113 Sources: World Bank; UNDP-HDR, ILO Territorial organisation and subnational government RESPONSIBILITIES MUNICIPAL LEVEL INTERMEDIATE LEVEL REGIONAL OR STATE LEVEL TOTAL NUMBER OF SNGs 483 - - 483 Local governments - Municipalities (baladiyeh) Average municipal size: 8 892 inhabitantS Main features of territorial organisation. The Palestinian Authority was born from the Oslo Agreements. Palestine is divided into two main geographical units: the West Bank and the Gaza Strip. It is still an ongoing State construction. The official government of Cisjordania is governed by a President, while the Gaza area is governed by the Hamas. Up to now, most governmental functions are ensured by the State of Israel. In 1994, and upon the establishment of the Palestinian Ministry of Local Government (MoLG), 483 local government units were created, encompassing 103 municipalities and village councils and small clusters. Besides, 16 governorates are also established as deconcentrated level of government. -

Women in Palestinian Refugee Camps: Case Studies from Lebanon, Jordan and Palestine

The Atkin Paper Series Women in Palestinian Refugee Camps: Case Studies from Lebanon, Jordan and Palestine Manar Faraj ICSR Atkin Fellow June 2015 About the Atkin Paper Series To be a refugee is hard, but to be a woman and a refugee is the hardest Thanks to the generosity of the Atkin Foundation, the International Centre for the Study of Radicalisation and Political Violence (ICSR) offers young leaders from Israel of all and the Arab world the opportunity to come to London for a period of four months. The purpose of the fellowship is to provide young leaders from Israel and the Arab he aim of this paper is to take the reader on a journey into the lived world with an opportunity to develop their ideas on how to further peace and experiences of Palestinian refugee women, in several stages. First, I offer understanding in the Middle East through research, debate and constructive dialogue Tan introduction to the historical roots and struggles of Palestinian refugee in a neutral political environment. The end result is a policy paper that will provide a women. This is followed by case studies drawn from my field research in refugee deeper understanding and a new perspective on a specific topic or event. camps in Palestine, Lebanon and Jordan. The third part of the paper includes recommendations for improving the participation of refugee women in the social Author and political arenas of these refugee camps. Three main questions have driven the Manar Faraj is from the Dhiesheh Refugee Camp, Bethlehem, Palestine. She is research for this paper: What is the role of women in the refugee camps? What currently a PhD candidate at Jena Univserity. -

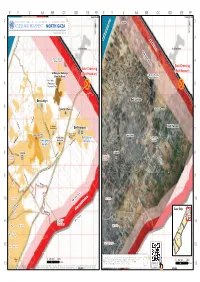

Urban Planning Analyses of Refugee Camps, Jabalia As Case Study-Gaza Strip, Palestine

International Journal of Science and Research (IJSR) ISSN (Online): 2319-7064 Index Copernicus Value (2013): 6.14 | Impact Factor (2015): 6.391 Urban Planning Analyses of Refugee Camps, Jabalia as Case Study-Gaza Strip, Palestine Dr. Usama Ibrahim Badawy1, Dr Ra’ed A. Salha2, Dr. Muain Qasem Jawabrah3, Amjad Jarada4 Mohammed A. EL Hawajri5 1Former Professor of Architecture, Birzeit University Palestine, works currently at UNRWA 2Assistant Professor, Islamic University of Gaza in Geography and GIS Palestine 3Assistance Professor, Architecture Department, Birzeit University Palestine 4Researcher in Infrastructure Planning and Development works currently at UNRWA, G, 5Researcher Geography subjects, works currently as teacher by the Ministry of Education Abstract: The Gaza Strip is a tight area with more than 1.8 million inhabitants. Since the beginning of the last century, and as other Palestinian areas, Gaza Strip was subject to direct occupation. The occupation tightened laws and regulations and increased obstacles, meanwhile it established settlements in a method that besieges existing Palestinian urban areas and leads them to develop in a way that serves the occupation, particularly the security side. This research begins with background information on Palestinian refugees in Gaza, sees that camp Improvement Strategies should called for adoption of the future urban planning, increasing the accommodation capacity of the built-up area, activating the environmental resources protection laws and played down the issue of the land properties when preparing the comprehensive plans. In this study reviews options for addressing the problems faced by Palestinian refugees in Gaza, Recommendations: After discussing the topic through a analyses of the Current Conditions , Land availability, Population distribution, Land requirements, Overcrowding, Public Spaces problems inside the camps , Sustainability in Gaza Strip, socio-economic situation , Unemployment problem and Population density in Jabalia Camp. -

North Gaza ¥ August 2011 ¥ 3 3 Mediterranean Sea No-Go Zone

No Fishing Zone 1.5 nautical miles 3 nautical miles X Y Z AA BB CC DD EE FF X Y Z AA BB CC DD EE FF Yad Mordekhai Yad Mordekhai 2 United Nations OfficeAs-Siafa for the Coordination of Humanitarian Affairs As-Siafa 2 ACCESS AND MOVEMENT - NORTH GAZA ¥ auGUST 2011 ¥ 3 3 Mediterranean Sea No-Go Zone Al-Rasheed Netiv ha-Asara Netiv ha-Asara High Risk Zone Temporary Wastewater 4 Treatment Lagoons 4 Erez Crossing Erez Crossing Al Qaraya al Badawiya (Beit Hanoun) (Beit Hanoun) Al Qaraya al Badawiya (Umm An-Naser) (Umm An-Naser) Beit Lahia 5 Wastewater 5 Treatment Plant Beit Lahiya Beit Lahiya 6 6 'Izbat Beit Hanoun 'Izbat Beit Hanoun Al Mathaf Hotel Al-Sekka Al Karama Al Karama El-Bahar Beit Lahia Main St. Arc-Med Hotel Al-Faloja Sheikh Zayed Beit Hanoun Housing Project Beit Hanoun Madinat al 'Awda 7 v®Madinat al 'Awda 7 Beit Hanoun Jabalia Camp v® Industrial Jabalia Camp 'Arab Maslakh Zone Beit Hanoun 'Arab Maslakh Kamal Edwan Beit Lahya Beit Lahya Abu Ali Eyad Kamal Edwan Hospital Al-Naser Al-Saftawi Hospital Khalil Al-Wazeer Ahmad Sadeq Ash Shati' Camp Said El-Asi Jabalia Jabalia An Naser 8 Al-quds An Naser 8 El-Majadla Ash Sheikh Yousef El-Adama Ash Sheikh Al-Sekka Radwan Radwan Falastin Khalil El-Wazeer Al Deira Hotel Ameen El Husaini Heteen Salah El-Deen ! Al-Yarmook Saleh Dardona Abu Baker Al-Razy Palestine Stadium Al-Shifa Al-Jalaa 9 9 Hospital ! Al-quds Northern Rimal Al-Naffaq Al-Mashahra El-Karama Northern Rimal Omar El-Mokhtar Southern Rimal Al-Wehda Al-Shohada Al Azhar University Ad Daraj G Ad Daraj o v At Tuffah e At Tuffah 10 r 10 n High Risk Zone Islamic ! or Al-Qanal a University Yafa t e Haifa Jamal Abdel Naser Al-Sekka 500 meter NO-Go Zone Salah El-Deen Gaza Strip Beit Lahiya Al-Qahera Khalil Al-Wazeer J" Boundar J" y JabalyaJ" Al-Aqsa As Sabra Gaza City Beit Hanun Gaza City Marzouq GazaJ" City Northern Gaza Al-Dahshan Wire Fence Al 'Umari11 Wastewater 11 Mosque Moshtaha Treatment Plant Tal El Hawa Ijdeedeh Ijdeedeh Deir alJ" Balah Old City Bagdad Old City Rd No. -

Gaza CRISIS)P H C S Ti P P I U

United Nations Office for the Coordination of Humanitarian Affairs occupied Palestinian territory Zikim e Karmiya s n e o il Z P m A g l in a AGCCESSA ANDZ AMOV EMENTSTRI (GAZA CRISIS)P h c s ti P P i u F a ¥ SEPTEMBER 2014 o nA P N .5 F 1 Yad Mordekhai EREZ CROSSING (BEIT HANOUN) occupied Palestinian territory: ID a As-Siafa OPEN, six days (daytime) a B?week4 for B?3the4 movement d Governorates e e of international workers and limited number of y h s a b R authorized Palestinians including aid workers, medical, P r 2 e A humanitarian cases, businessmen and aid workers. Jenin d 1 e 0 Netiv ha-Asara P c 2 P Tubas r Tulkarm r fo e S P Al Attarta Temporary Wastewater P n b Treatment Lagoons Qalqiliya Nablus Erez Crossing E Ghaboon m Hai Al Amal r Fado's 4 e B? (Beit Hanoun) Salfit t e P P v i Al Qaraya al Badawiya i v P! W e s t R n m (Umm An-Naser) n i o » B a n k a North Gaza º Al Jam'ia ¹¹ M E D I TER RAN EAN Hatabiyya Ramallah da Jericho d L N n r n r KJ S E A ee o Beit Lahia D P o o J g Wastewater Ed t Al Salateen Beit Lahiya h 5 Al Kur'a J a 9 P l D n Treatment Plant D D D D 9 ) D s As Sultan D 1 2 El Khamsa D " Sa D e J D D l i D 0 D s i D D 0 D D d D D m 2 9 Abedl Hamaid D D r D D l D D o s D D a t D D c Jerusalem D D c n P a D D c h D D i t D D s e P! D D A u P 0 D D D e D D D a l m d D D o i t D D l i " D D n . -

THE PLO and the PALESTINIAN ARMED STRUGGLE by Professor Yezid Sayigh, Department of War Studies, King's College London

THE PLO AND THE PALESTINIAN ARMED STRUGGLE by Professor Yezid Sayigh, Department of War Studies, King's College London The emergence of a durable Palestinian nationalism was one of the more remarkable developments in the history of the modern Middle East in the second half of the 20th century. This was largely due to a generation of young activists who proved particularly adept at capturing the public imagination, and at seizing opportunities to develop autonomous political institutions and to promote their cause regionally and internationally. Their principal vehicle was the Palestine Liberation Organization (PLO), while armed struggle, both as practice and as doctrine, was their primary means of mobilizing their constituency and asserting a distinct national identity. By the end of the 1970s a majority of countries – starting with Arab countries, then extending through the Third World and the Soviet bloc and other socialist countries, and ending with a growing number of West European countries – had recognized the PLO as the legitimate representative of the Palestinian people. The United Nations General Assembly meanwhile confirmed the right of the stateless Palestinians to national self- determination, a position adopted subsequently by the European Union and eventually echoed, in the form of support for Palestinian statehood, by the United States and Israel from 2001 onwards. None of this was a foregone conclusion, however. Britain had promised to establish a Jewish ‘national home’ in Palestine when it seized the country from the Ottoman Empire in 1917, without making a similar commitment to the indigenous Palestinian Arab inhabitants. In 1929 it offered them the opportunity to establish a self-governing agency and to participate in an elected assembly, but their community leaders refused the offer because it was conditional on accepting continued British rule and the establishment of the Jewish ‘national home’ in what they considered their own homeland. -

Convention on the Elimination of All Forms of Discrimination Against Women on 1 April 2014, Without Submitting Reservations to Any of Its Articles

United Nations CEDAW/C/PSE/1 Convention on the Elimination Distr.: General 24 May 2017 of All Forms of Discrimination English against Women Original: Arabic Committee on the Elimination of Discrimination against Women Consideration of reports submitted by States parties under article 18 of the Convention pursuant to the simplified reporting procedure Initial reports of States parties due in 2015 * State of Palestine [Date received: 10 March 2017] Note: The present document is being circulated in Arabic, English, French and Spanish only. * The present document is being issued without formal editing. 17-08413 (E) 070717 270717 *1708413* CEDAW/C/PSE/1 Contents Page I. Introduction .................................................................. 3 II. Information relating to the substantive articles of the Convention ...................... 4 Part 1 .............................................................................. 4 Article 1 ..................................................................... 4 Article 2 ..................................................................... 5 Article 3 ..................................................................... 14 Article 4 ..................................................................... 16 Article 5 ..................................................................... 17 Article 6 ..................................................................... 23 Part 2 .............................................................................. 25 Articles 7-8 .................................................................