A Review of Journalism in Iran

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Manifestation of Modernity in Iranian Public Squares: Baharestan Square (1826–1978)

Asma Mehan, Int. J. of Herit. Archit., Vol. 1, No. 3 (2017) 411–420 MANIFESTATION OF MODERNITY IN IRANIAN PUBLIC SQUARES: BAHARESTAN SQUARE (1826–1978) ASMA MEHAN Department of Architecture and Design, Politecnico Di Torino, Italy. ABSTRACT The concept of public square has changed significantly in Iran in recent centuries. This research inves- tigated how modernity is manifested in the public squares of Tehran. In this regard, Tehran has been chosen as the main concern, while in its short history as the capital of Iran, the city has been critically transformed: first because of constant urban development during the Qajar Dynasty and then due to its rapid growth during the late Pahavi era and second because of the culture of rapid renovation and reconstruction in contemporary public spaces. Considering these facts, the urban transformation of Baharestan Square as one of the most influencing public squares of Tehran in the recent century leads us to understand the process of Iranian modernization, which is totally different from common patterns of western modernity. Analysing the historical changes of Baharestan Square based on manuscripts, western travellers’ diaries, historical images and maps, from its formation till the Islamic Revolution (1978), shows how the traditional elements of the square as well as its form and function have been totally transformed. Analysing the spatial qualities of Baharestan Square clarifies that its special loca- tion near the first Iranian Parliament building, Sepahsalar Mosque and Negarestan Garden represents it as the first modern focal point in Iranian’s political and social life. Keywords: Baharestan Square, Iranian modernity, public square, Tehran. -

Republic of Uzbekistan QUICK FACTS UZBEKISTAN

Republic of Uzbekistan QUICK FACTS UZBEKISTAN ............................................................................ The telecommunications market of Uzbekistan is in the Land Area: 425, 400 sq km process of saturation and is one of the fastest growing Population: 28.2 million sectors of the economy. Uzbekistan has the highest rate GNI per capita, PPP $3,110 (WB, 2010) of growth in the number of mobile subscribers in the CIS. The growth rate of revenues from mobile services TLD: .uz lags behind the pace of growth in the number of mobile Fixed Telephones: 1.9 million (2010) subscribers. There were 24.3 million mobile subscribers GSM Telephones: 24.3 million (2011) to the end of 2011.83 Fixed Broadband: 0.15 million (2010) Internet Users: 8.8 million (2012) TELECOMMUNICATIONS MARKET Indicator80 Measurement Value Computers Per 100 n/a Kazakstan Internet Users Per 100 31.2 Fixed Lines Per 100 6.6 Internet Broadband Per 100 0.3 Uzbekistan Kyrgyzstan Mobile Subscriptions Per 100 84.0 Mobile Broadband Per 100 19.9 (est) Turkmenistan Tajikistan International Bandwidth Per 100 17.2 kb Iran There have been no changes in number of operators Afghanistan in the last 3 years: “MTS” brand from “Uzdunrobita” (established June 1991) GSM/UMTS; “Beeline” brand from “Unitel” (established in April 1996) GSM/UMTS; In August 2011, all mobile operators in Uzbekistan 84 “Ucell” brand from “COSCOM” (established in April suspended internet and messaging services for the 1996) GSM/UMTS; “Perfectum Mobile” brand from duration of university entrance exams in an attempt to “Rubicon Wireless Communication” (established in prevent cheating. Five national mobile operators shut November 1996) CDMA 2001X; “UzMoble” brand from down mobile internet, text, and picture messaging JSC “Uzbektelecom” (established in August 2000) for four hours from 9 am local time, citing “urgent CDMA-450. -

Iran and Turkey: the Yin and Yang of the Islamic World by Whitney Mason

Iran and Turkey: The Yin and Yang of the Islamic World By Whitney Mason Since the zenith of Arab power in the tenth century; it's been a perennial con- tender for leadership of the entire Islamic world. A vast country of snow-capped mountains, high grazing lands and wind-whipped deserts bestriding a strategic land bridge between two seas, two worlds. A country of bewildering diversity often riven by localized insurrections yet ruled through most of its long history by a single hereditary monarch. A country torn between its fierce pride in its unique culture and its determination to escape servitude to the West by adopting the in- stitutions and technologies that for the last few centuries have allowed Europeans to dominate the world. A country that for centuries made painful sacrifices of sovereign rights in exchange for protection from its predatory neighbor to the north, Russia. A country where the ideological ferment of the 1920s swept the traditional monarchy from power and replaced it with an autocrat bent on west, ernizing his country at any cost including breaking the back of the religious establishment. A country where a progressive president committed to pluralism is now vying with entrenched interests whose power depends on the monopoli- zation of ideas in general and religion in particular. This description applies equally to two countries and to two countries alone: Turkey and Iran. Indeed, Turkey and Iran who represent, along with Egypt, the great pow- ers of the Middle East are mirror images of one another. Each regards the other as an apostate from a faith they once shared in common. -

Modernizing the Public Space: Gender Identities

MODERNIZING THE PUBLIC SPACE: GENDER IDENTITIES, MULTIPLE MODERNITIES, AND SPACE POLITICS IN TEHRAN A DISSERTATION IN Geosciences and Sociology Presented to the Faculty of the University of Missouri-Kansas City in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree DOCTOR OF PHILOSOPHY by NAZGOL BAGHERI Bachelor of Architecture, 2004 Bachelor of Computer Science, 2006 Master of Urban Design, 2007 Shahid Beheshti University, Tehran, Iran Kansas City, Missouri 2013 © 2013 NAZGOL BAGHERI ALL RIGHTS RESERVED MODERNIZING THE PUBLIC SPACE: GENDER IDENTITIES, MULTIPLE MODERNITIES, AND SPACE POLITICS IN TEHRAN Nazgol Bagheri, Candidate for the Doctor of Philosophy Degree University of Missouri - Kansas City, 2013 ABSTRACT After the Islamic Revolution of 1979 in Iran, surprisingly, the presence of Iranian women in public spaces dramatically increased. Despite this recent change in women’s presence in public spaces, Iranian women, like in many other Muslim-majority societies in the Middle East, are still invisible in Western scholarship, not because of their hijabs but because of the political difficulties of doing field research in Iran. This dissertation serves as a timely contribution to the limited post-revolutionary ethnographic studies on Iranian women. The goal, here, is not to challenge the mainly Western critics of modern and often privatized public spaces, but instead, is to enrich the existing theories through including experiences of a more diverse group. Focusing on the women’s experience, preferences, and use of public spaces in Tehran through participant observation and interviews, photography, architectural sketching as well as GIS spatial analysis, I have painted a picture of the complicated relationship between the architecture styles, the gendering of spatial boundaries, and the contingent nature of public spaces that goes beyond the simple dichotomy of female- male, private-public, and modern-traditional. -

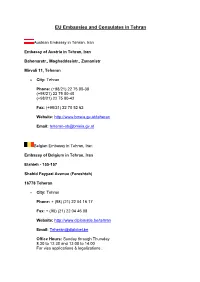

EU Embassies and Consulates in Tehran

EU Embassies and Consulates in Tehran Austrian Embassy in Tehran, Iran Embassy of Austria in Tehran, Iran Bahonarstr., Moghaddasistr., Zamanistr Mirvali 11, Teheran City: Tehran Phone: (+98/21) 22 75 00-38 (+98/21) 22 75 00-40 (+98/21) 22 75 00-42 Fax: (+98/21) 22 70 52 62 Website: http://www.bmeia.gv.at/teheran Email: [email protected] Belgian Embassy in Tehran, Iran Embassy of Belgium in Tehran, Iran Elahieh - 155-157 Shahid Fayyazi Avenue (Fereshteh) 16778 Teheran City: Tehran Phone: + (98) (21) 22 04 16 17 Fax: + (98) (21) 22 04 46 08 Website: http://www.diplomatie.be/tehran Email: [email protected] Office Hours: Sunday through Thursday 8.30 to 12.30 and 13.00 to 14.00 For visa applications & legalizations : Sunday through Tuesday from 8.30 to 11.30 AM Bulgarian Embassy in Tehran, Iran Bulgarian Embassy in Tehran, Iran IR Iran, Tehran, 'Vali-e Asr' Ave. 'Tavanir' Str., 'Nezami-ye Ganjavi' Str. No. 16-18 City: Tehran Phone: (009821) 8877-5662 (009821) 8877-5037 Fax: (009821) 8877-9680 Email: [email protected] Croatian Embassy in Tehran, Iran Embassy of the Republic of Croatia in Tehran, Iran 1. Behestan 25 Avia Pasdaran Tehran, Islamic Republic of Iran City: Tehran Phone: 0098 21 258 9923 0098 21 258 7039 Fax: 0098 21 254 9199 Email: [email protected] Details: Covers the Islamic Republic of Pakistan, Islamic Republic of Afghanistan Details: Ambassador: William Carbó Ricardo Cypriot Embassy in Tehran, Iran Embassy of the Republic of Cyprus in Tehran, Iran 328, Shahid Karimi (ex. -

Iran Threat Reduction and Syria Human Rights Act of 4 2012’’

In the House of Representatives, U. S., August 1, 2012. Resolved, That the House agree to the amendment of the Senate to the bill (H.R. 1905) entitled ‘‘An Act to strengthen Iran sanctions laws for the purpose of compelling Iran to abandon its pursuit of nuclear weapons and other threatening activities, and for other purposes.’’, with the following HOUSE AMENDMENT TO SENATE AMENDMENT: In lieu of the matter proposed to be inserted by the amendment of the Senate, insert the following: 1 SECTION 1. SHORT TITLE; TABLE OF CONTENTS. 2 (a) SHORT TITLE.—This Act may be cited as the 3 ‘‘Iran Threat Reduction and Syria Human Rights Act of 4 2012’’. 5 (b) TABLE OF CONTENTS.—The table of contents for 6 this Act is as follows: Sec. 1. Short title; table of contents. Sec. 2. Definitions. TITLE I—EXPANSION OF MULTILATERAL SANCTIONS REGIME WITH RESPECT TO IRAN Sec. 101. Sense of Congress on enforcement of multilateral sanctions regime and expansion and implementation of sanctions laws. Sec. 102. Diplomatic efforts to expand multilateral sanctions regime. TITLE II—EXPANSION OF SANCTIONS RELATING TO THE ENERGY SECTOR OF IRAN AND PROLIFERATION OF WEAPONS OF MASS DESTRUCTION BY IRAN Subtitle A—Expansion of the Iran Sanctions Act of 1996 Sec. 201. Expansion of sanctions with respect to the energy sector of Iran. 2 Sec. 202. Imposition of sanctions with respect to transportation of crude oil from Iran and evasion of sanctions by shipping companies. Sec. 203. Expansion of sanctions with respect to development by Iran of weapons of mass destruction. Sec. -

5. Kurdish Tribes

Country Policy and Information Note Iraq: Blood feuds Version 1.0 August 2017 Preface This note provides country of origin information (COI) and policy guidance to Home Office decision makers on handling particular types of protection and human rights claims. This includes whether claims are likely to justify the granting of asylum, humanitarian protection or discretionary leave and whether – in the event of a claim being refused – it is likely to be certifiable as ‘clearly unfounded’ under s94 of the Nationality, Immigration and Asylum Act 2002. Decision makers must consider claims on an individual basis, taking into account the case specific facts and all relevant evidence, including: the policy guidance contained with this note; the available COI; any applicable caselaw; and the Home Office casework guidance in relation to relevant policies. Country Information COI in this note has been researched in accordance with principles set out in the Common EU [European Union] Guidelines for Processing Country of Origin Information (COI) and the European Asylum Support Office’s research guidelines, Country of Origin Information report methodology, namely taking into account its relevance, reliability, accuracy, objectivity, currency, transparency and traceability. All information is carefully selected from generally reliable, publicly accessible sources or is information that can be made publicly available. Full publication details of supporting documentation are provided in footnotes. Multiple sourcing is normally used to ensure that the information is accurate, balanced and corroborated, and that a comprehensive and up-to-date picture at the time of publication is provided. Information is compared and contrasted, whenever possible, to provide a range of views and opinions. -

Study of the Impact of Form Enclosure in Residential

Science Arena Publications Specialty Journal of Architecture and Construction Available online at www.sciarena.com 2016, Vol 2 (2): 43-52 Study Of The Impact Of Form Enclosure In Residential Complexes On The Sense Of Place Attachment Of Residents (Case study: Shahrakee Ekbatan and Shahrakee Gharb residential complexes)1 Seyedeh Sarah Qodsi1, Jamaluddin Soheili2 1- Department of architecture ,Barajin Science and Research College, Islamic Azad University ,Qazvin, Iran [email protected] (+98) 9124900159 2- Faculty member and assistant professor ,Islamic Azad University ,Qazvin ,Iran (Corresponding) [email protected] (+98) 9123816120 Abstract: The attachment and belonging to the environment in the traditional neighborhood life has always contributed to a sense of responsibility in the residents relative to each other and the city and establishing social partnerships. Today, major changes have occurred in the lifestyle and social communications especially among the neighbors. This has resulted in indifference and separation of the citizens from each other and also from the events that occur within the city and the neighborhood. The increasing process of weakening social relations will eventually lead to social disconnectedness. Since the traditional neighborhoods in Iran enjoyed a built-in enclosure and hierarchy and such enclosure had a significant impact on the residents’ sense of place attachment, this question comes to mind that whether the enclosed form of a residential complex can also affect the level of the inhabitants’ sense of place attachment similar to the traditional neighborhoods? Hence, in this paper we have attempted to examine the lives of the residents of the residential complexes such as Shahrake Ekbatan and Shahrake Gharb in the Greater Tehran to come up with a clear answer to the raised question. -

NEWSLETTER CENTER for IRANIAN STUDIES NEWSLETTER Vol

CIS NEWSLETTER CENTER FOR IRANIAN STUDIES NEWSLETTER Vol. 13, No.2 MEALAC–Columbia University–New York Fall 2001 Encyclopædia Iranica: Volume X Published Fascicle 1, Volume XI in Press With the publication of fascicle ISLAMIC PERSIA: HISTORY AND 6 in the Summer of 2001, Volume BIOGRAPHY X of the Encyclopædia Iranica was Eight entries treat Persian his- completed. The first fascicle of Vol- tory from medieval to modern ume XI is in press and will be pub- times, including “Golden Horde,” lished in December 2001. The first name given to the Mongol Khanate fascicle of volume XI features over 60 ruled by the descendents of Juji, the articles on various aspects of Persian eldest son of Genghis Khan, by P. Jack- culture and history. son. “Golshan-e Morad,” a history of the PRE-ISLAMIC PERSIA Zand Dynasty, authored by Mirza Mohammad Abu’l-Hasan Ghaffari, by J. Shirin Neshat Nine entries feature Persia’s Pre-Is- Perry. “Golestan Treaty,” agreement lamic history and religions: “Gnosti- arranged under British auspices to end at Iranian-American Forum cism” in pre-Islamic Iranian world, by the Russo-Persian War of 1804-13, by K. Rudolph. “Gobryas,” the most widely On the 22nd of September, the E. Daniel. “Joseph Arthur de known form of the old Persian name Encyclopædia Iranica’s Iranian-Ameri- Gobineau,” French man of letters, art- Gaub(a)ruva, by R. Schmitt. “Giyan ist, polemist, Orientalist, and diplomat can Forum (IAF) organized it’s inau- Tepe,” large archeological mound lo- who served as Ambassador of France in gural event: a cocktail party and pre- cated in Lorestan province, by E. -

The Poetics of Commitment in Modern Persian: a Case of Three Revolutionary Poets in Iran

The Poetics of Commitment in Modern Persian: A Case of Three Revolutionary Poets in Iran by Samad Josef Alavi A dissertation submitted in partial satisfaction of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in Near Eastern Studies in the Graduate Division of the University of California, Berkeley Committee in Charge: Professor Shahwali Ahmadi, Chair Professor Muhammad Siddiq Professor Robert Kaufman Fall 2013 Abstract The Poetics of Commitment in Modern Persian: A Case of Three Revolutionary Poets in Iran by Samad Josef Alavi Doctor of Philosophy in Near Eastern Studies University of California, Berkeley Professor Shahwali Ahmadi, Chair Modern Persian literary histories generally characterize the decades leading up to the Iranian Revolution of 1979 as a single episode of accumulating political anxieties in Persian poetics, as in other areas of cultural production. According to the dominant literary-historical narrative, calls for “committed poetry” (she‘r-e mota‘ahhed) grew louder over the course of the radical 1970s, crescendoed with the monarch’s ouster, and then faded shortly thereafter as the consolidation of the Islamic Republic shattered any hopes among the once-influential Iranian Left for a secular, socio-economically equitable political order. Such a narrative has proven useful for locating general trends in poetic discourses of the last five decades, but it does not account for the complex and often divergent ways in which poets and critics have reconciled their political and aesthetic commitments. This dissertation begins with the historical assumption that in Iran a question of how poetry must serve society and vice versa did in fact acquire a heightened sense of urgency sometime during the ideologically-charged years surrounding the revolution. -

Timothy May on Genghis Khan and the Making of the Modern World

Jack Weatherford. Genghis Khan and the Making of the Modern World. New York: Crown Publishers, 2004. xxxv + 312 pp. $25.00, cloth, ISBN 978-0-609-61062-6. Reviewed by Timothy May Published on H-World (March, 2005) The name of Genghis Khan is often associated cluding with an epilogue, notes, glossary, and bib‐ with destruction, although the image of Genghis liography. Preceding all of these is a genealogical Khan has been rehabilitated somewhat in the table showing Genghis Khan, his sons, and the west. The western world, saturated in media dis‐ successor khanates. In addition to showing the tortion and a reluctance to accept changes in per‐ rulers of the empire, the terms of the regents are ceptions of history, has been rather averse in ac‐ designated. The latter is something that is often cepting Genghis Khan's activities as pivotal in remiss in these sorts of tables, but a welcome ad‐ world history and the shaping of the modern dition here. There is an odd segment of the table world. Thus, the publication of Jack Weatherford's though. All of the Khanates or states resulting book, Genghis Khan and the Making of the Mod‐ from the split of the Mongol Empire are shown ern World, is a welcome addition to the literature except the Chaghatayid Khanate of Central Asia. on the Mongols. In its place is the Moghul Empire of India. Indeed, The author, Jack Weatherford, the Dewitt the Moghul Empire has connections back to the Wallace Professor of Anthropology at Macalester Mongols (Moghul is Persian for Mongol), but the College, has written several books targeted for the founder of the Moghul Empire, Babur, was him‐ non-academic world and writes in a very engag‐ self a Timurid, the dynasty of the Emir Timur, ing style. -

KHERAD-DISSERTATION-2013.Pdf

Copyright by Nastaran Narges Kherad 2013 The Dissertation Committee for Nastaran Narges Kherad Certifies that this is the approved version of the following dissertation: RE-EXAMINING THE WORKS OF AHMAD MAHMUD: A FICTIONAL DEPICTION OF THE IRANIAN NATION IN THE SECOND HALF OF THE 20TH CENTURY Committee: M.R. Ghanoonparvar, Supervisor Kamran Aghaie Kristen Brustad Elizabeth Richmond-Garza Faegheh Shirazi RE-EXAMINING THE WORKS OF AHMAD MAHMUD: A FICTIONAL DEPICTION OF THE IRANIAN NATION IN THE SECOND HALF OF THE 20TH CENTURY by Nastaran Narges Kherad, B.A.; M.A. Dissertation Presented to the Faculty of the Graduate School of The University of Texas at Austin in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree of Doctor of Philosophy The University of Texas at Austin May 2013 Dedication Dedicated to my son, Manai Kherad-Aminpour, the joy of my life. May you grow with a passion for literature and poetry! And may you face life with an adventurous spirit and understanding of the diversity and complexity of humankind! Acknowledgements The completion of this dissertation could not have been possible without the ongoing support of my committee members. First and for most, I am grateful to Professor Ghanoonparvar, who believed in this project from the very beginning and encouraged me at every step of the way. I thank him for giving his time so generously whenever I needed and for reading, editing, and commenting on this dissertation, and also for sharing his tremendous knowledge of Persian literature. I am thankful to have the pleasure of knowing and working with Professor Kamaran Aghaei, whose seminars on religion I cherished the most.