Mausoleum the Mausoleum of Augustus

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Rodolfo Lanciani, the Ruins and Excavations of Ancient Rome, 1897, P

10/29/2010 1 Primus Adventus ad Romam Urbem Aeternam Your First Visit to Rome The Eternal City 2 Accessimus in Urbe AeternA! • Welcome, traveler! Avoiding the travails of the road, you arrived by ship at the port of Ostia; from there, you’ve had a short journey up the Via Ostiensis into Roma herself. What do you see there? 3 Quam pulchra est urbs aeterna! • What is there to see in Rome? • What are some monuments you have heard of? • How old are the buildings in Rome? • How long would it take you to see everything important? 4 Map of Roma 5 The Roman Forum • “According to the Roman legend, Romulus and Tatius, after the mediation of the Sabine women, met on the very spot where the battle had been fought, and made peace and an alliance. The spot, a low, damp, grassy field, exposed to the floods of the river Spinon, took the name of “Comitium” from the verb coire, to assemble. It is possible that, in consequence of the alliance, a road connecting the Sabine and the Roman settlements was made across these swamps; it became afterwards the Sacra Via…. 6 The Roman Forum • “…Tullus Hostilius, the third king, built a stone inclosure on the Comitium, for the meeting of the Senators, named from him Curia Hostilia; then came the state prison built by Ancus Marcius in one of the quarries (the Tullianum). The Tarquin [kings] drained the land, gave the Forum a regular (trapezoidal) shape, divided the space around its borders into building- lots, and sold them to private speculators for shops and houses, the fronts of which were to be lined with porticoes.” --Rodolfo Lanciani, The Ruins and Excavations of Ancient Rome, 1897, p. -

A Study of the Pantheon Through Time Caitlin Williams

Union College Union | Digital Works Honors Theses Student Work 6-2018 A Study of the Pantheon Through Time Caitlin Williams Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalworks.union.edu/theses Part of the Ancient History, Greek and Roman through Late Antiquity Commons, and the Classical Archaeology and Art History Commons Recommended Citation Williams, Caitlin, "A Study of the Pantheon Through Time" (2018). Honors Theses. 1689. https://digitalworks.union.edu/theses/1689 This Open Access is brought to you for free and open access by the Student Work at Union | Digital Works. It has been accepted for inclusion in Honors Theses by an authorized administrator of Union | Digital Works. For more information, please contact [email protected]. A Study of the Pantheon Through Time By Caitlin Williams * * * * * * * Submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for Honors in the Department of Classics UNION COLLEGE June, 2018 ABSTRACT WILLIAMS, CAITLIN A Study of the Pantheon Through Time. Department of Classics, June, 2018. ADVISOR: Hans-Friedrich Mueller. I analyze the Pantheon, one of the most well-preserVed buildings from antiquity, through time. I start with Agrippa's Pantheon, the original Pantheon that is no longer standing, which was built in 27 or 25 BC. What did it look like originally under Augustus? Why was it built? We then shift to the Pantheon that stands today, Hadrian-Trajan's Pantheon, which was completed around AD 125-128, and represents an example of an architectural reVolution. Was it eVen a temple? We also look at the Pantheon's conversion to a church, which helps explain why it is so well preserVed. -

Front Matter

Cambridge University Press 978-1-107-02320-8 - Campus Martius: The Field of Mars in the Life of Ancient Rome Paul W. Jacobs II and Diane Atnally Conlin Frontmatter More information CAMPUS MARTIUS A mosquito-infested and swampy plain lying north of the city walls, Rome’s Campus Martius, or Field of Mars, was used for much of the Roman Republic as a military training ground and as a site for celebratory rituals and the occasional political assembly. Initially punctuated with temples vowed by victorious generals, during the imperial era it became filled with extraordinary baths, theaters, porticoes, aqueducts, and other structures – many of which were architectural firsts for the capital. This book explores the myriad factors that contributed to the transformation of the Campus Martius from an occasionally visited space to a crowded center of daily activity. It presents a case study of the repurposing of urban landscape in the Roman world and explores how existing topographical features that fit well with the republic’s needs ultimately attracted architecture that forever transformed those features but still resonated with the area’s original military and ceremonial traditions. Paul W. Jacobs II is an independent scholar who focuses on ancient Rome and its topographical development. A graduate of Harvard College and the University of Virginia Law School, and a litigator by training, Jacobs has practiced and published in the area of voting rights, where knowledge of demographics, mapmaking, and geography is essential. He has spent extensive time in Rome and has studied the ancient city and its development for decades. Diane Atnally Conlin is Associate Professor of Classics at the University of Colorado, Boulder. -

(Michelle-Erhardts-Imac's Conflicted Copy 2014-06-24).Pages

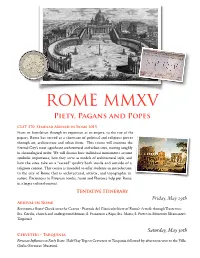

ROME MMXV Piety, Pagans and Popes CLST 370: Seminar Abroad in Rome 2015 From its foundation through its expansion as an empire, to the rise of the papacy, Rome has served as a showcase of political and religious power through art, architecture and urban form. This course will examine the Eternal City’s most significant architectural and urban sites, moving roughly in chronological order. We will discuss how individual monuments assume symbolic importance, how they serve as models of architectural style, and how the sites take on a “sacred” quality both inside and outside of a religious context. This course is intended to offer students an introduction to the city of Rome that is architectural, artistic, and topographic in nature. Excursions to Etruscan tombs, Assisi and Florence help put Rome in a larger cultural context. " Tentative Itinerary" Friday, May 29th! Arrival in Rome Benvenuto a Roma! Check into the Centro - Piazzale del Gianicolo (view of Rome) -A walk through Trastevere: Sta. Cecilia, church and underground domus; S. Francesco a Ripa; Sta. Maria; S. Pietro in Montorio (Bramante’s Tempietto)." Saturday, May 30th! Cerveteri - Tarquinia Etruscan Influences on Early Rome. Half-Day Trip to Cerveteri or Tarquinia followed by afternoon visit to the Villa " Giulia (Etruscan Museum). ! Sunday, May 31st! Circus Flaminius Foundations of Early Rome, Military Conquest and Urban Development. Isola Tiberina (cult of Asclepius/Aesculapius) - Santa Maria in Cosmedin: Ara Maxima Herculis - Forum Boarium: Temple of Hercules Victor and Temple of Portunus - San Omobono: Temples of Fortuna and Mater Matuta - San Nicola in Carcere - Triumphal Way Arcades, Temple of Apollo Sosianus, Porticus Octaviae, Theatre of Marcellus. -

The Original Documents Are Located in Box 16, Folder “6/3/75 - Rome” of the Sheila Weidenfeld Files at the Gerald R

The original documents are located in Box 16, folder “6/3/75 - Rome” of the Sheila Weidenfeld Files at the Gerald R. Ford Presidential Library. Copyright Notice The copyright law of the United States (Title 17, United States Code) governs the making of photocopies or other reproductions of copyrighted material. Gerald R. Ford donated to the United States of America his copyrights in all of his unpublished writings in National Archives collections. Works prepared by U.S. Government employees as part of their official duties are in the public domain. The copyrights to materials written by other individuals or organizations are presumed to remain with them. If you think any of the information displayed in the PDF is subject to a valid copyright claim, please contact the Gerald R. Ford Presidential Library. Digitized from Box 16 of the Sheila Weidenfeld Files at the Gerald R. Ford Presidential Library 792 F TO C TATE WA HOC 1233 1 °"'I:::: N ,, I 0 II N ' I . ... ROME 7 480 PA S Ml TE HOUSE l'O, MS • · !? ENFELD E. • lt6~2: AO • E ~4SSIFY 11111~ TA, : ~ IP CFO D, GERALD R~) SJ 1 C I P E 10 NTIA~ VISIT REF& BRU SE 4532 UI INAl.E PAL.ACE U I A PA' ACE, TME FFtCIA~ RESIDENCE OF THE PR!S%D~NT !TA y, T ND 0 1 TH HIGHEST OF THE SEVEN HtL.~S OF ~OME, A CTENT OMA TtM , TH TEMPLES OF QUIRl US AND TME s E E ~oc T 0 ON THIS SITE. I THE CE TER OF THE PR!SENT QU?RINA~ IAZZA OR QUARE A~E ROMAN STATUES OF C~STOR .... -

Rome Historic Trail ……………..…

Rome, Italy HISTORIC TRAIL ROME, ITALY TRANSATLANTICHISTORIC COUNCIL TRAIL How to Use This Guide This Field Guide contains information on the Rome Historical Trail designed by a members of the Transatlantic Council. The guide is intended to be a starting point in your endeavor to learn about the history of the sites on the trail. Remember, this may be the only time your Scouts visit Rome in their life so make it a great time! While TAC tries to update these Field Guides when possible, it may be several years before the next revision. If you have comments or suggestions, please send them to [email protected] or post them on the TAC Nation Facebook Group Page at https://www.facebook.com/groups/27951084309/. This guide can be printed as a 5½ x 4¼ inch pamphlet or read on a tablet or smart phone. Front Cover: Saint Peter’s Basilica in the Vatican City Front Cover Inset: Roman Coliseum ROME, ITALY 2 HISTORIC TRAIL Table of Contents Getting Prepared………………..…………4 What is the Historic Trail…….……… 5 Rome Historic Trail ……………..…. 6-24 Route Maps & Pictures……..….. 25-28 Quick Quiz……………………….……………29 B.S.A. Requirements………….…..…… 30 Notes……………………………..….………… 31 ROME, ITALY HISTORIC TRAIL 3 Getting Prepared Just like with any hike (or any activity in Scouting), the Historic Trail program starts with Being Prepared. 1. Review this Field Guide in detail. 2. Check local conditions and weather. 3. Study and Practice with the map and compass. 4. Pack rain gear and other weather-appropriate gear. 5. Take plenty of water. 6. Make sure socks and hiking shoes or boots fit correctly and are broken in. -

Green Building Evaluation of the Roman Pantheon Using Fuzzy Set Concept

Green Building Evaluation of the Roman Pantheon Using Fuzzy Set Concept. THESIS Presented in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree Master of Science in the Graduate School of The Ohio State University By Nina Frances Parshall, B.S. Graduate Program in Civil Engineering The Ohio State University 2016 Master's Examination Committee: Dr. Fabian Tan, Advisor Dr. Frank Croft Dr. Lisa Abrams Copyright by Nina Frances Parshall 2016 Abstract This research focuses on the ancient green building evaluation of the Roman Pantheon, use the fuzzy set concept. In today’s society and in the future, there will be pressure from society to continue to make improvements on green building design and construction, and this research aims to advance current green building evaluations. An ancient building, such as, the Roman Pantheon was used for this research because it can provide great insight to ancient design and construction practices, many of which have been forgotten over the years. The green building evaluation first begins with the evaluation of specific green building categories including Site Selection, Use of Water, Energy Conservation, Materials and Resources, Air Quality, and Innovation of Design and Construction. Each category is rated based on the subcategories, which are assigned linguistic rating values. The linguistic values range from extremely non-green to extremely green. After all linguistic ratings are assigned, a weight average is calculated to determine the category rating and the total greenness rating of the Pantheon. While the weighted average can provide a total green building rating for a structure, it does not take into account the unclearly defined linguistic expressions. -

The Symbolic Use of Light in Hadrianic Architecture and the 'Kiss of the Sun'

Archaeoastronomy and Ancient Technologies 2018, 6(1), 111-137; http://aaatec.org/art/a_fm1 www.aaatec.org ISSN 2310-2144 The Symbolic Use of Light in Hadrianic Architecture and the 'Kiss of the Sun' Marina De Franceschini1,*, Giuseppe Veneziano 2 1 Independent researcher in collaboration with Astronomical Observatory of Genoa, Via Superiore Gazzo, Genova, GE 16153, ALSSA, Italy; E-Mail: [email protected] 2 Astronomical Observatory of Genoa, Via Superiore Gazzo, Genova, GE 16153, ALSSA, Italy; E-Mail: [email protected] Abstract In this presentation we will discuss three Roman monuments of the times of Emperor Hadrian (117- 138 AD): the Villa Adriana at Tivoli near Rome, the Mausoleum of Hadrian in Rome (now Castel Sant'Angelo) and finally the Pantheon (also in Rome). In all of them we see luminous phenomena which occur only in few set days during the year; they correspond to astronomical events such as the Solstices or other important dates of the Roman calendar. As we will see, this did not happen by chance and had a precise symbolic meaning. Also, we will explain why there are no written sources about Roman oriented buildings and their illuminations, producing an ancient and rare documentation: the description of the "Kiss of the Sun". Keywords: Archaeoastronomy, Pantheon Arc of Light, Hadrian’s Villa, Mausoleum of Hadrian, Roman religion, Roman Calendar, Emperor Hadrian, Pontifex Maximus, Solstice, Roccabruna, Accademia 1. Villa Adriana The authors of this article studied Archaeoastronomy at Villa Adriana (Hadrian’s Villa1 at Tivoli, Rome), where they discovered the astronomical orientation of the building called Accademia and of the Accademia Esplanade (De Franceschini, Veneziano, 2011, pp. -

The Role of the Sun in the Pantheon's Design and Meaning

The role of the sun in the Pantheon’s design and meaning Robert Hannah Giulio Magli Department of Classics Faculty of Civil Architecture University of Otago Politecnico di Milano P.O. Box 56 P.le Leonardo da Vinci 32 Dunedin 9054 20133 Milan New Zealand Italy [email protected] [email protected] Abstract Despite being one of the most recognisable buildings from ancient Rome, the Pantheon is poorly understood. While its architecture has been well studied, its function remains uncertain. This paper argues that both the design and the meaning of the Pantheon are in fact dependent upon an understanding of the role of the sun in the building, and of the apotheosised emperor in Roman thought. Supporting evidence is drawn not only from the instruments of time in the form of the roofed spherical sundial, but also from other Imperial monuments, notably Nero’s Domus Aurea and Augustus’s complex of structures on the Campus Martius – his Ara Pacis, the ‘Horologium Augusti’, and his Mausoleum. Hadrian’s Mausoleum and potentially part of his Villa at Tivoli are drawn into this argument as correlatives. Ultimately, it is proposed that sun and time were linked architecturally into cosmological signposts for those Romans who could read such things. 1 Keywords Pantheon, sun, Mausoloeum of Hadrian, Domus Aurea, ‘Horologium Augusti, Ara Pacis 1. Introduction The Pantheon is the best preserved architectural monument of the Roman period in Rome (fig. 1). Originally built by Agrippa around 27 BC under Augustus’s rule, it was destroyed by fire under Domitian, then rebuilt and finally completed in its present form during Hadrian’s reign, in ca. -

The Campus Martius

For I shall sing of Battels, Blood and Rage, Which Princes and their People did engage, And haughty Souls, that mov’d with mutual Hate, In fighting Fields pursued and found their Fate – Virgil, The Aeneid, 19 BC. Book VII, verse 40. Translated by John Dryden (1697). The empire was forged on the Field of Mars, where Roman soldiers drilled and armies assembled under the auspices of the god of war. Here, outside the pomerium, men could bear weapons, the Senate could meet generals in arms and foreign envoys, foreign gods could be worshipped. With the advent of the Pax Romana, the Campus Martius was singularly marked by two friends, Agrippa, the great general, and Octavian, the first emperor, who built monuments there to celebrate not war but peace. By the end of the first century AD, the central Campus Martius was filled to bursting with public buildings, houses, baths, theatres, temples, and monuments. Five centuries later, when mighty Rome was a thing of the past and the aqueducts were cut or in disrepair, people concentrated in this area close to the Tiber, their only water supply, making their houses, shops, and churches in the magnificent remains. Those ancient walls form the modern fabric of this part of Rome, which then like today, was busy, noisy, crowded, confusing, and fascinating. 1 Below: The Roman Army on the march. Soldiers and standard-bearers (wearing animal heads, the emblems of their cohort) on the Column of Marcus Aurelius. Before the 1st century AD, this floodplain was a sort of commons belonging to everyone, used for pasture, as drilling grounds, and for assembling armies. -

The Pantheon: from Antiquity to the Present

One Introduction Tod A. Marder and Mark Wilson Jones Astonishing for its scale and magnificence as for its preservation, rich in history and meanings, the Pantheon exerts a perpetual fascination. Written accounts, visual representations, and architectural progeny from late antiquity to our day combine to create a presence at once unique and universal in the Western architectural tradition. The Venerable Bede declared that whoever leaves Rome without seeing the Pantheon leaves Rome a fool, and this dictum seems no less valid for our time than when it was first uttered, according to legend, in the eighth century. Visitors may marvel at its unexpected majesty even as they experience a sense of déjà vu, having already encountered its resonant reflection in buildings from other epochs on different continents. Indeed, the Pantheon straddles the history of Western architecture like a colossus, its influence perhaps more pervasive than for any other single building in history (Fig. 1.1, Plate I).1 1.1. View of Pantheon facade, piazza, and fountain. (The Bern Digital Pantheon Project, BERN BDPP0101) I. Exterior view of the Pantheon. (Photo Roberto Lucignani) This influence has been generous and elastic, inspiring not only copies but creative reinterpretations like Hagia Sophia in Istanbul, St. Peter’s in Rome, the Capitol in Washington, and the Parliament of Bangladesh. No less diverse are the associations that such projects exploit, which can be sacred or secular, political or religious. Simultaneously a symbol of cultural stability or revolutionary change, the Pantheon is a remarkably vigorous and mutable icon.2 The fame of the Pantheon is of course bound up with its imagery, and its imagery with its structure. -

Reading the Mausoleum of Augustus in Rome a Thesis

READING THE MAUSOLEUM OF AUGUSTUS IN ROME A THESIS SUBMITTED TO THE GRADUATE SCHOOL OF SOCIAL SCIENCES OF MIDDLE EAST TECHNICAL UNIVERSITY BY MERAL ÖZDENGİZ BAŞAK IN PARTIAL FULFILLMENT OF THE REQUIREMENTS FOR THE DEGREE OF MASTER OF ARTS IN THE DEPARTMENT OF HISTORY OF ARCHITECTURE FEBRUARY 2020 Approval of the Graduate School of Social Sciences Prof. Dr. Yaşar Kondakçı Director I certify that this thesis satisfies all the requirements as a thesis for the degree of Master of Arts. Prof. Dr. Cânâ Bilsel Head of Department This is to certify that we have read this thesis and that in our opinion it is fully adequate, in scope and quality, as a thesis for the degree of Master of Arts. Prof. Dr. Suna Güven Supervisor Examining Committee Members Assist. Prof. Dr. Pelin Yoncacı Arslan (METU, AH) Prof. Dr. Suna Güven (METU, AH) Assist. Prof. Dr. İdil Üçer Karababa (İstanbul Bilgi Uni., IND) I hereby declare that all information in this document has been obtained and presented in accordance with academic rules and ethical conduct. I also declare that, as required by these rules and conduct, I have fully cited and referenced all material and results that are not original to this work. Name, Last name : Meral Özdengiz Başak Signature : iii ABSTRACT READING THE MAUSOLEUM OF AUGUSTUS IN ROME ÖZDENGİZ BAŞAK, Meral M.A., Department of History of Architecture Supervisor: Prof. Dr. Suna GÜVEN February 2020, 199 pages This thesis focuses on the Mausoleum of the first Roman Emperor Augustus in Rome. It studies the Mausoleum as a Roman monument highly laden with symbolic meanings and functions.