Sand, Innersand and Garderhouse: Place-Names In

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Cornwall's New Aberdeen Directory

M. 7£ Digitized by the Internet Archive in 2010 with funding from National Library of Scotland http://www.archive.org/details/cornwallsnewaber185354abe CORNWALL^ NEW ABERDEEN DIRECTORY, 1853 54; COMPRISING A NEW GENERAL DIRECTORY; NEW TRADES' AND PROFESSIONS' DIRECTORY; NEW STREET DIRECTORY; NEW COTTAGE, VILLA, & SUBURBAN DIRECTORY; NEW PUBLIC INSTITUTIONS DIRECTORY; NEW COUNTY DIRECTORY; ETC. ETC. ETC. ABERDEEN: GEO. CORNWALL, 54, CASTLE STREET. 1853. ft? *•£*.••• > £ NOTE BY THE PUBLISHER. It is due to the Public to state that, in order to procure informa- tion for the " City " portion of this Directory, from Five to Six Thousand Schedules were issued, for the purpose of being filled up by the Inhabitants. In transcribing these Schedules, the utmost care was taken to preserve the exact address and orthography of Name which had been given; and, still farther to preserve the accuracy of the Work, the ' whole of the Names, after they had been put into type, were again, at a large sacrifice of time, care- fully compared, one by one, with the original Schedules. The " County " Directory, which forms an important part of the Work, has been made up from returns furnished, in almost every instance, by the Schoolmasters of the respective Parishes. To the Gentlemen who have thus so kindly assisted him, the Publisher gladly embraces the present opportunity of returning his most grateful thanks. The short delay which has occurred in getting the Work issued, has been as much a disappointment to the Publisher as it can have been to his Subscribers. To those of them, however, who may have been incommoded by the delay, he begs to offer a respectful apology, and to assure them that, from the complicated and laborious nature of the Work, (this Directory being an entirely new compilation), the delay was found to be quite un- avoidable. -

Sandsting & Aithsting Community Council

Sandsting & Aithsting Community Council Chairman: Clerk: Mr John Priest Mrs L Fraser Farmhouse West Burrafirth Reawick Walls Shetland Shetland ZE2 9NJ ZE2 9NT Tel: 01595 860274 Tel: Walls 01595 809203 e-mail: [email protected] e-mail: [email protected] Minutes of a WebEx meeting of Sandsting & Aithsting Community Council held on Monday 11 January 2021 at 7.30pm. 0800 051 3810 128 693 7972 Present: J Priest Ms D Nicolson G Morrison J D Garrick Mrs S Deyell M Bennett Mrs J Fraser Ex officio: Cllr C Hughson Cllr T Smith By invitation: Ms Beatrice Wishart MSP In attendance: Mrs R Fraser, Community Involvement & Development Worker. Mrs L Fraser, Clerk Mr J Priest presiding The Chairman welcomed everyone to the meeting and asked for a roll call so that everyone knew who was there no matter in which order they signed in. APOLOGIES: Apologies for absence were received from Cllr S Coutts and Mr M Duncan, Community Liaison Officer. MINUTES & HEADLINES: The minutes of the meeting held on 14 December 2020, having been circulated, were taken as read and were approved. Moved by Mr M Bennett, seconded by Ms D Nicolson. MS BEATRICE WISHART, MSP: The Chairman then welcomed Ms B Wishart MSP to the meeting. She said she appreciated being invited to join us. Coronavirus - Ms B Wishart explained that she had been contacting Community Councils to see how they are coping as she felt that it is important to retain contact in order to understand how the community is coping with the present circumstances. She agreed that people were feeling a bit more comfortable before the last outbreak but that there are now 3 vaccines available which are in the process of being rolled out. -

Orcadian Basin Devonian Extensional Tectonics Versus Carboniferous

Journal of the Geological Society Devonian extensional tectonics versus Carboniferous inversion in the northern Orcadian basin M. SERANNE Journal of the Geological Society 1992; v. 149; p. 27-37 doi:10.1144/gsjgs.149.1.0027 Email alerting click here to receive free email alerts when new articles cite this article service Permission click here to seek permission to re-use all or part of this article request Subscribe click here to subscribe to Journal of the Geological Society or the Lyell Collection Notes Downloaded by INIST - CNRS trial access valid until 31/05/2008 on 31 March 2008 © 1992 Geological Society of London Journal of the Geological Society, London, Vol. 149, 1992, pp. 21-31, 14 figs, Printed in Northern Ireland Devonian extensional tectonics versus Carboniferous inversion in the northern Orcadian basin M. SERANNE Laboratoire de Gdologie des Bassins, CNRS u.a.1371, 34095 Montpellier cedex 05, France Abstract: The Old Red Sandstone (Middle Devonian) Orcadian basin was formed as a consequence of extensional collapse of the Caledonian orogen. Onshore study of these collapse-basins in Orkney and Shetland provides directions of extension during basin development. The origin of folding of Old Red Sandstone sediments, that has generally been related to a Carboniferous inversion phase, is discussed: syndepositional deformation supports a Devonian age and consequently some of the folds are related to basin formation. Large-scale folding of Devonian strata results from extensional and left-lateral transcurrent faulting of the underlying basement. Spatial variation of extension direction and distribution of extensional and transcurrent tectonics fit with a model of regional releasing overstep within a left- lateral megashear in NW Europe during late-Caledonian extensional collapse. -

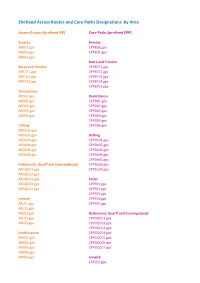

Shetland Access Routes and Core Paths Codes by Area

Shetland Access Routes and Core Paths Designations by Area Access Routes (prefixed AR) Core Paths (prefixed CPP) Bressay Bressay ARB01.gpx CPPB01.gpx ARB02.gpx CPPB02.gpx ARB03.gpx Burra and Trondra Burra and Trondra CPPBT01.gpx ARBT01.gpx CPPBT02.gpx ARBT02.gpx CPPBT03.gpx ARBT03.gpx CPPBT04.gpx CPPBT05.gpx Dunrossness ARD01.gpx Dunrossness ARD03.gpx CPPD01.gpx ARD04.gpx CPPD02.gpx ARD05.gpx CPPD03.gpx ARD06.gpx CPPD04.gpx CPPD05.gpx Delting CPPD06.gpx ARDe01.gpx ARDe02.gpx Delting ARDe03.gpx CPPDe01.gpx ARDe04.gpx CPPDe02.gpx ARDe06.gpx CPPDe03.gpx ARDe08.gpx CPPDe04.gpx CPPDe05.gpx Gulberwick, Quarff and Cunningsburgh CPPDe06.gpx ARGQC01.gpx CPPDe07.gpx ARGQC02.gpx ARGQC03.gpx Fetlar ARGQC04.gpx CPPF01.gpx ARGQC05.gpx CPPF02.gpx CPPF03.gpx Lerwick CPPF04.gpx ARL01.gpx CPPF05.gpx ARL02.gpx ARL03.gpx Gulberwick, Quarff and Cunningsburgh ARL04.gpx CPPGQC01.gpx ARL05.gpx CPPGQC02.gpx CPPGQC03.gpx Northmavine CPPGQC04.gpx ARN01.gpx CPPGQC05.gpx ARN02.gpx CPPGQC06.gpx ARN03.gpx CPPGQC07.gpx ARN04.gpx ARN05.gpx Lerwick CPPL01.gpx Nesting and Lunnasting CPPL02.gpx ARNL01.gpx CPPL03.gpx ARNL02.gpx CPPL04.gpx ARNL03.gpx CPPL05.gpx CPPL06.gpx Sandwick ARS01.gpx Northmavine ARS02.gpx CPPN01.gpx ARS03.gpx CPPN02.gpx ARS04.gpx CPPN03.gpx CPPN04.gpx Sandsting and Aithsting CPPN05.gpx ARSA04.gpx CPPN06.gpx ARSA05.gpx CPPN07.gpx ARSA07.gpx CPPN08.gpx ARSA10.gpx CPPN09.gpx CPPN10.gpx Scalloway CPPN11.gpx ARSC01.gpx CPPN12.gpx ARSC02.gpx CPPN13.gpx Skerries Nesting and Lunnasting ARSK01.gpx CPPNL01.gpx CPPNL03.gpx Tingwall, Whiteness and Weisdale CPPNL04.gpx -

Shetland and Orkney Island-Names – a Dynamic Group Peder Gammeltoft

Shetland and Orkney Island-Names – A Dynamic Group Peder Gammeltoft 1. Introduction Only when living on an island does it become clear how important it is to know one‟s environment in detail. This is no less true for Orkney and Shetland. Being situated in the middle of the North Atlantic, two archipelagos whose land-mass consist solely of islands, holms and skerries, it goes without saying that such features are central, not only to local life and perception, but also to travellers from afar seeking shelter and safe passage. Island, holms and skerries appear to be fixed points in an ever changing watery environment – they appear to be constant and unchanging – also with regard to their names. And indeed, several Scandinavian researchers have claimed that the names of islands constitute a body of names which, by virtue of constant usage and relevance over time, belong among the oldest layers of names (cf. e.g. Hald 1971: 74-75; Hovda 1971: 124-148). Archaeological remains on Shetland and Orkney bear witness to an occupation of these archipelagos spanning thousands of years, so there can be little doubt that these areas have been under continuous utilisation by human beings for a long time, quite a bit longer, in fact, than our linguistic knowledge can take us back into the history of these isles. So, there is nothing which prevents us from assuming that names of islands, holms and skerries may also here carry some of the oldest place-names to be found in the archipelagos. Since island-names are often descriptive in one way or another of the locality bearing the name, island-names should be able to provide an insight into the lives, strategies and needs of the people who eked out an existence in bygone days in Shetland and Orkney. -

1851 Census (Shetland).Xlsx

Wishart Surname in the 1851 UK Census (Shetland, Scotland) Forename Surname Age Sex Address Civil Parish Occupation Relationship Condition Birthplace Birth County Country Henry Wishart 41 Male Commercial Street Lerwick Sailor Head Unmarried Nesting Shetland Scotland Penelope Wishart 50 Female Craigies Court Lerwick House Servant Servant Unmarried Nesting Shetland Scotland Adam Wishart 50 Male 3 Reform Lane Lerwick Sailor Lodger Married Weesdale Shetland Scotland Hugh Wishart 70 Male Torrisdale Lunnasting Pauper (Formerly Crofter & Fisher) Head Married Skelberry Shetland Scotland May Wishart 73 Female Torrisdale Lunnasting Pauper Wife Married Delting Shetland Scotland Catherine Wishart 30 Female Torrisdale Lunnasting Agricultural Labourer Daughter Unmarried Skelberry Shetland Scotland Laura Wishart 30 Female Torrisdale Lunnasting Knitting & Spinning Daughter Widow Skelberry Shetland Scotland Catherine Wishart 6 M Female Torrisdale Lunnasting Grandaughter Skelberry Shetland Scotland Joanna Wishart 18 Female Catfirth Nesting Labouring Servant Unmarried Nesting Shetland Scotland Janet Wishart 70 Female Quays Nesting Pauper Visitor Unmarried Brough (Nesting) Shetland Scotland Robert Wishart 47 Male Aswick Nesting Fishing & Labouring Head Married Bensten (Nesting) Shetland Scotland Elizabeth Wishart 46 Female Aswick Nesting Labouring Wife Married Aswick (Nesting) Shetland Scotland Agnes Wishart 20 Female Aswick Nesting Labouring Daughter Unmarried Aswick (Nesting) Shetland Scotland David Wishart 17 Male Aswick Nesting Fishing & Labouring Son -

127639442.23.Pdf

•KlCi-fr-CT0! , Xit- S»cs fS) hcyi'* SCOTTISH HISTORY SOCIETY FOURTH SERIES VOLUME 4 The Court Books of Orkney and Shetland The Earl's Palace, Kirkwall, Orkney Scalloway Castle, Shetland THE COURT BOOKS OF Orkney and Shedand 1614-1615 transcribed and edited by Robert S. Barclay B.SC., PH.D., F.R.S.E. EDINBURGH printed for the Scottish History Society by T. AND A. CONSTABLE LTD I967 Scottish History Society 1967 ^iG^Feg ^ :968^ Printed in Great Britain PREFACE My warmest thanks are due to Mr John Imrie, Curator of Historical Records, H.M. General Register House, and to Professor Gordon Donaldson of the Department of Scottish History, Edinburgh University, for their scholarly advice so freely given, and for their unfailing courtesy. R.S.B. Edinburgh June, 1967 : A generous contribution from the Carnegie Trust for the Universities of Scotland towards the cost of producing this volume is gratefully acknowledged by the Council of the Society CONTENTS Preface page v INTRODUCTION page xi The Northern Court Books — The Court Books described Editing the transcript - The historical setting The scope of the Court Books THE COURT BOOK OF THE BISHOPRIC OF ORKNEY 1614- 1615 page 1 THE COURT BOOK OF ORKNEY 1615 page 11 THE COURT BOOK OF SHETLAND 1615 page 57 Glossary page 123 Index page 129 03 ILLUSTRATIONS The Earl’s Palace, Kirkwall, Orkney Scalloway Castle, Shetland Crown copyright photographs reproduced by permission of Ministry of PubUc Building and Works frontispiece Facsimile from Court Book of Orkney, folio 49V. page 121 m INTRODUCTION THE NORTHERN COURT BOOKS This is the third volume printed in recent years of proceedings in the sheriff courts of Orkney and Shetland in the early decades of the seventeenth century. -

A Late Norse Church in South Uist 333

Proc SocAntiq Scot, 122 (1992), 329-350 Cille Donnain lata : e Norse churc Soutn hi h Uist Andrew Fleming Ale*& x Woolf* ABSTRACT On a promontory on the western edge of Loch Kildonan, South Uist, in the Western Isles, are the ruins of a church known as Cille Donnain. The paper argues that this church and some buildings nearbythe on Eilean Mor (reached causeways)by constituted importantan 12th-century religious and political centre, comparable to Finlaggan in Islay; it is suggested that the site may have been the seat of a bishop. The church lies within an earlier dun-like site, which is also described, with suggestions about earlier loch levels here. INTRODUCTION The site described here lies on what is now a promontory on the western edge of upper Loch Kildonan (NGR NF 731 282). It is about 2 km south-east of Rubha Ardvule, the most conspicuous headlan wese th tn dcoaso Soutf to h Uist (illus }-4). The site is known to local people, and was marked on the first edition (1881) of the 6-inch Ordnance Survey map as 'Cille Donnain' (in Gothic lettering) and 'Ancient Burial Ground (disused)' t appearI currene . th n o se aret s th 'Cill1:10,00a f o ep Donnai0ma n (site of)'. However RCAHMe th , S volumaree th ar reporteefo d that 'n obuildiny tracvisiblean w f eno o s gi ' (1928, 120) Royae Th . l Commission's investigator visite aree dth a onl day8 y1 s afte outbreae th r k of the First World War, so his mind may have been on other matters. -

Family Information Directory

Shetland Family Information Directory Information on services and sources of support for families living and working in Shetland 2 Contents Childcare 4 Work and Finance 18 Family Support 21 Community Involvement 30 Family Information 32 Activities and Leisure 38 Services for Young People 43 Health 44 Disclaimer: While we have made every effort to ensure the accuracy of the information in this booklet, we disclaim any warranty or representation, expressed or implied about its accuracy, completeness or appropriateness for a particular purpose. Neither NHS Shetland, Shetland Islands Council not any of their employees are responsible or liable for any claim, loss or damage resulting from its use. These agencies are not responsible for the contents or reliability of the websites listed and do not necessarily endorse the views expressed within them. Inclusion in this Directory shall not be taken as endorsement of any kind. Printed May 2012 3 Family Information Being a parent can be the most challenging and rewarding task anyone will undertake. Access to good quality information about services, activities and sources of support can make a big difference and help you to make informed choices for you and for your family. This Directory has been compiled by organisations in Shetland, who are working to support the well being of families in these islands. It is hoped that families and those working with parents, carers and children will all benefit from this source of information. This information was correct at the time of printing, if you find inaccuracies, or have suggestions for additional information, which would be useful to include, please let us know. -

A Lost Radiocarbon Date for Shetland R C Barcham*

A lost radiocarbon date for Shetland R C Barcham* CaldeT n 1949I S C r, excavate site sidf Stanydal dth eo W f Mainland eo e th n eo e th , largest island in the Shetland group. He later described this site as a Neolithic temple on the basis of some very broad morphological similarities with the Maltese temple of Mnaidra (Calder 1950,203-5) subsequens .Hi t identificatio excavatiod nan thif o s E dwellinstructura S f no m 0 g20 e knowd same an th ey nb nam ee architectura suggesteth m hi thud o temporade t an th sl l con- nexions between house and 'temple' and also prompted a fresh perception of the prehistoric landscape of Shetland. His hypotheses were tested favourably by further excavations at Gruting School - perhaps less ambiguously called Scutta Voe - and at Ness of Gruting (ibid, 343-56). * 24 Whitehaven Road, Horndean, Hants SHORTER3 NOTE50 | S Four house-sites and their congruent field systems were noted in an area of abandoned croftland at Ness of Grating. Two of these sites (NGR HU 277484 & 277845) were briefly examined with trial trenches lattee sincs ;th rha e beeburna s na reclassifietS moundO e th y .db The interior of a third site (HU 281483) was totally excavated. The walls of the structure were cleared and have been left standing. The excavated house measured 17-4 m by 11-6 m. Its walls were up to 4-7 m thick and attained a maximum height of 0-9 m. Within the core of the walling an enormous quantity of peat ash was found, sometimes supplemented by stones and brown soil, containing numerous sherds which were tentatively explained as the residue of a potter's work- shop. -

Orkney and Shetland

Orkney and Shetland: A Landscape Fashioned by Geology Orkney and Shetland Orkney and Shetland are the most northerly British remnants of a mountain range that once soared to Himalayan heights. These Caledonian mountains were formed when continents collided around A Landscape Fashioned by Geology 420 million years old. Alan McKirdy Whilst the bulk of the land comprising the Orkney Islands is relatively low-lying, there are spectacular coastlines to enjoy; the highlight of which is the magnificent 137m high Old Man of Hoy. Many of the coastal cliffs are carved in vivid red sandstones – the Old Red Sandstone. The material is also widely used as a building stone and has shaped the character of the islands’ many settlements. The 12th Century St. Magnus Cathedral is a particularly fine example of how this local stone has been used. OrKney A Shetland is built largely from the eroded stumps of the Caledonian Mountains. This ancient basement is pock-marked with granites and related rocks that were generated as the continents collided. The islands of the Shetland archipelago are also fringed by spectacular coastal features, nd such as rock arches, plunging cliffs and unspoilt beaches. The geology of Muckle Flugga and the ShetLAnd: A LA Holes of Scraada are amongst the delights geologists and tourists alike can enjoy. About the author Alan McKirdy has worked in conservation for over thirty years. He has played a variety of roles during that period; latterly as Head of Information Management at SNH. Alan has edited the Landscape nd Fashioned by Geology series since its inception and anticipates the completion of this 20 title series ScA shortly. -

The Shetland Times | Friday, 2Nd July, 2021 | 27 PUBLIC NOTICES

The Shetland Times | Friday, 2nd July, 2021 | 27 PUBLIC NOTICES THE OFFSHORE OIL AND GAS EXPLORATION, PRODUCTION, UNLOADING AND STORAGE (ENVIRONMENTAL IMPACT ASSESSMENT) Denotes extents REGULATIONS 2020 of roadworks RHUM PRODUCTION INCREASE As advised in a public notice published Friday 11 June 2021, Serica Energy (UK) Limited has made an application for consent to the Oil and Gas Authority (“the OGA”) in relation to the above project. Since publication of the original notice, a BEATRICE WISHART MSP number of corrections have been implemented in the associated environmental Member of the Scottish Parliament for impact assessment (“EIA”) which is now available for review. Those corrections are: Shetland Islands Constituency $EEUHYLDWLRQVŋ((06DGGHG6HFWLRQ$DQG$ŋOLFHQVHHQDPHFODULĠFDWLRQ$ – top row of table reformatted, B2 – WIA number updated and Bruce quadrant/ CONSTITUENCY block numbers corrected, Introduction – unit of measurement changed to million P 6HFWLRQ ŋ SLSHOLQH GHVFULSWRUV DPHQGHG 6HFWLRQ ŋ ORFDWLRQ FODULĠHG DV ADVICE SURGERIES H[LVWLQJŋEORFNQDPHVFRUUHFWHG7DEOHŋWLWOHVDPHQGHG7DEOHŋWLWOH DPHQGHGFRUUHFWLRQRIQXPHULFDOYDOXHVDQGIRRWQRWHDGGHGDQG6HFWLRQŋ WH[WXSGDWHLQĠQDOSDUDJUDSKŋGLHVHODGGHG Monday 5th July, 2021 Summary of Project North Roe & Lochend Hall The project involves a workover of the R3 well to increase production levels from the Rhum Field. The R3 well will produce condensate and gas to the Rhum central 11am-11:45am PDQLIROGWKDWLVWLHGEDFNWRWKH%UXFHSODWIRUP Źłń1RUWKŹłń(DVW /RFDWHGLQWKH116LQEORFNWKHDVVRFLDWHGVXEVHDLQIUDVWUXFWXUHLQFOXGHVWKH