This Thesis Has Been Submitted in Fulfilment of the Requirements for a Postgraduate Degree (E.G

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Inverness Active Travel A2 2021

A9 To Wick / Thurso 1 D Ord Hill r Charleston u m s m B it el M t lfie i a ld ll F l A96 To Nairn / Aberdeen R b e Rd Recommended Cycle Routes d a r r Map Key n y City Destinations k B rae Craigton On road School / college / university Dual carriageway Railway Great Glen Way Lower Cullernie Main road Built up area On road - marked cycle lane South Loch Ness Trail Business park / other business Blackhill O a kl eigh R O road - shared foot / cycle path Bike shop dRetail park INVERNESS ACTIVE TRAVEL MAP Minor road Buildings 1 Mai Nutyle North n St 1 P Track Woodland O road - other paths and tracks Bike hire Kessock Visitor attraction o int Rd suitable for cycling Bike repair Hospital / medical centre Path / steps Recreation areas 78 National Cycle Network A9 Balmachree Ke One way trac Church Footbridge Railway station ss Dorallan oc k (contraow for bikes) Steep section (responsible cycling) Br id Bus station ge Allanfearn Upper (arrows pointing downhill) Campsite Farm Cullernie Wellside Farm Visitor information 1 Gdns Main road crossing side Ave d ell R W d e R Steps i de rn W e l l si Railway le l d l P Carnac u e R Crossing C d e h D si Sid t Point R Hall ll rk i r e l a K M W l P F e E U e Caledonian Thistle e d M y I v k W i e l S D i r s a Inverness L e u A r Football a 7 C a dBalloch Merkinch Local S T D o Milton of P r o a Marina n Balloch U B w e O S n 1 r y 1 a g Stadium Culloden r L R B Nature Reserve C m e L o m P.S. -

Cornwall's New Aberdeen Directory

M. 7£ Digitized by the Internet Archive in 2010 with funding from National Library of Scotland http://www.archive.org/details/cornwallsnewaber185354abe CORNWALL^ NEW ABERDEEN DIRECTORY, 1853 54; COMPRISING A NEW GENERAL DIRECTORY; NEW TRADES' AND PROFESSIONS' DIRECTORY; NEW STREET DIRECTORY; NEW COTTAGE, VILLA, & SUBURBAN DIRECTORY; NEW PUBLIC INSTITUTIONS DIRECTORY; NEW COUNTY DIRECTORY; ETC. ETC. ETC. ABERDEEN: GEO. CORNWALL, 54, CASTLE STREET. 1853. ft? *•£*.••• > £ NOTE BY THE PUBLISHER. It is due to the Public to state that, in order to procure informa- tion for the " City " portion of this Directory, from Five to Six Thousand Schedules were issued, for the purpose of being filled up by the Inhabitants. In transcribing these Schedules, the utmost care was taken to preserve the exact address and orthography of Name which had been given; and, still farther to preserve the accuracy of the Work, the ' whole of the Names, after they had been put into type, were again, at a large sacrifice of time, care- fully compared, one by one, with the original Schedules. The " County " Directory, which forms an important part of the Work, has been made up from returns furnished, in almost every instance, by the Schoolmasters of the respective Parishes. To the Gentlemen who have thus so kindly assisted him, the Publisher gladly embraces the present opportunity of returning his most grateful thanks. The short delay which has occurred in getting the Work issued, has been as much a disappointment to the Publisher as it can have been to his Subscribers. To those of them, however, who may have been incommoded by the delay, he begs to offer a respectful apology, and to assure them that, from the complicated and laborious nature of the Work, (this Directory being an entirely new compilation), the delay was found to be quite un- avoidable. -

Sandsting & Aithsting Community Council

Sandsting & Aithsting Community Council Chairman: Clerk: Mr John Priest Mrs L Fraser Farmhouse West Burrafirth Reawick Walls Shetland Shetland ZE2 9NJ ZE2 9NT Tel: 01595 860274 Tel: Walls 01595 809203 e-mail: [email protected] e-mail: [email protected] Minutes of a WebEx meeting of Sandsting & Aithsting Community Council held on Monday 11 January 2021 at 7.30pm. 0800 051 3810 128 693 7972 Present: J Priest Ms D Nicolson G Morrison J D Garrick Mrs S Deyell M Bennett Mrs J Fraser Ex officio: Cllr C Hughson Cllr T Smith By invitation: Ms Beatrice Wishart MSP In attendance: Mrs R Fraser, Community Involvement & Development Worker. Mrs L Fraser, Clerk Mr J Priest presiding The Chairman welcomed everyone to the meeting and asked for a roll call so that everyone knew who was there no matter in which order they signed in. APOLOGIES: Apologies for absence were received from Cllr S Coutts and Mr M Duncan, Community Liaison Officer. MINUTES & HEADLINES: The minutes of the meeting held on 14 December 2020, having been circulated, were taken as read and were approved. Moved by Mr M Bennett, seconded by Ms D Nicolson. MS BEATRICE WISHART, MSP: The Chairman then welcomed Ms B Wishart MSP to the meeting. She said she appreciated being invited to join us. Coronavirus - Ms B Wishart explained that she had been contacting Community Councils to see how they are coping as she felt that it is important to retain contact in order to understand how the community is coping with the present circumstances. She agreed that people were feeling a bit more comfortable before the last outbreak but that there are now 3 vaccines available which are in the process of being rolled out. -

Achbeag, Cullicudden, Balblair, Dingwall IV7

Achbeag, Cullicudden, Balblair, Dingwall Achbeag, Outside The property is approached over a tarmacadam Cullicudden, Balblair, driveway providing parking for multiple vehicles Dingwall IV7 8LL and giving access to the integral double garage. Surrounding the property, the garden is laid A detached, flexible family home in a mainly to level lawn bordered by mature shrubs popular Black Isle village with fabulous and trees and features a garden pond, with a wide range of specimen planting, a wraparound views over Cromarty Firth and Ben gravelled terrace, patio area and raised decked Wyvis terrace, all ideal for entertaining and al fresco dining, the whole enjoying far-reaching views Culbokie 5 miles, A9 5 miles, Dingwall 10.5 miles, over surrounding countryside. Inverness 17 miles, Inverness Airport 24 miles Location Storm porch | Reception hall | Drawing room Cullicudden is situated on the Black Isle at Sitting/dining room | Office | Kitchen/breakfast the edge of the Cromarty Firth and offers room with utility area | Cloakroom | Principal spectacular views across the firth with its bedroom with en suite shower room | Additional numerous sightings of seals and dolphins to bedroom with en suite bathroom | 3 Further Ben Wyvis which dominates the skyline. The bedrooms | Family shower room | Viewing nearby village of Culbokie has a bar, restaurant, terrace | Double garage | EPC Rating E post office and grocery store. The Black Isle has a number of well regarded restaurants providing local produce. Market shopping can The property be found in Dingwall while more extensive Achbeag provides over 2,200 sq. ft. of light- shopping and leisure facilities can be found in filled flexible accommodation arranged over the Highland Capital of Inverness, including two floors. -

Clava-Cairns.Pdf

CLAVA CAIRNS CLAVA CAIRNS DISCOVER HISTORIC SCOTLAND THE SOUT H-WEST CAIRN THE NORT H-EAST CAIRN The Clava Cairns are cared for by Historic Scotland and owned by the National Trust for Scotland (NTS). VISITOR’S particularly important person was most probably interred ook into this well-preserved passage grave and see the workings They are free to visit and open all year. A inside this tomb, although recent excavations have found L of a sophisticated prehistoric timepiece. The SW cairn is just the no human remains associated with either passage grave. same. The low passageway that is aligned to the midwinter sunset once led into a central domed chamber that rose four metres. These cairns were the work of many people. But investigations of similar Discover other places to visit near the Clava Cairns: monuments suggest that only one or two people would have been buried Each stone slab used to line its walls was graded by height, with the tallest to the here. Like its twin, a decade after the SW cairn was raised, it was surrounded SW to face the setting sun. The distinctive kerbstones that surround the cairn’s by a cobbled platform and a stone circle. Two of the standing stones were base repeat that pattern, as does the circle of standing stones beyond.The stones moved in the 19th century. The Victorians, who believed the monument was were also chosen for their colour and texture. Those slabs lit by the sunset tend to a druidic temple, also planted trees to create a sacred grove. -

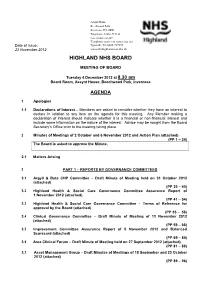

Full Set of Board Papers

Assynt House Beechwood Park Inverness, IV2 3BW Telephone: 01463 717123 Fax: 01463 235189 Textphone users can contact us via Date of Issue: Typetalk: Tel 0800 959598 23 November 2012 www.nhshighland.scot.nhs.uk HIGHLAND NHS BOARD MEETING OF BOARD Tuesday 4 December 2012 at 8.30 am Board Room, Assynt House, Beechwood Park, Inverness AGENDA 1 Apologies 1.1 Declarations of Interest – Members are asked to consider whether they have an interest to declare in relation to any item on the agenda for this meeting. Any Member making a declaration of interest should indicate whether it is a financial or non-financial interest and include some information on the nature of the interest. Advice may be sought from the Board Secretary’s Office prior to the meeting taking place. 2 Minutes of Meetings of 2 October and 6 November 2012 and Action Plan (attached) (PP 1 – 24) The Board is asked to approve the Minute. 2.1 Matters Arising 3 PART 1 – REPORTS BY GOVERNANCE COMMITTEES 3.1 Argyll & Bute CHP Committee – Draft Minute of Meeting held on 31 October 2012 (attached) (PP 25 – 40) 3.2 Highland Health & Social Care Governance Committee Assurance Report of 1 November 2012 (attached) (PP 41 – 54) 3.3 Highland Health & Social Care Governance Committee – Terms of Reference for approval by the Board (attached) (PP 55 – 58) 3.4 Clinical Governance Committee – Draft Minute of Meeting of 13 November 2012 (attached) (PP 59 – 68) 3.5 Improvement Committee Assurance Report of 5 November 2012 and Balanced Scorecard (attached) (PP 69 – 80) 3.6 Area Clinical Forum – Draft Minute of Meeting held on 27 September 2012 (attached) (PP 81 – 88) 3.7 Asset Management Group – Draft Minutes of Meetings of 18 September and 23 October 2012 (attached) (PP 89 – 96) 3.8 Pharmacy Practices Committee (a) Minute of Meeting of 12 September 2012 – Gaelpharm Limited (attached) (PP 97 – 118) (b) Minute of Meeting of 30 October 2012 – Mitchells Chemist Limited (attached) (PP 119 – 134) The Board is asked to: (a) Note the Minutes. -

Inverness Local Plan Public Local Inquiry Report

TOWN AND COUNTRY PLANNING (SCOTLAND) ACT 1997 REPORT OF PUBLIC LOCAL INQUIRY INTO OBJECTIONS TO THE INVERNESS LOCAL PLAN VOLUME 2 CITY OF INVERNESS Reporter: Janet M McNair MA(Hons) M Phil MRTPI File reference: IQD/2/270/7 Dates of the Inquiry: 14 April 2004 to 20 July 2004 INTRODUCTION TO VOLUME 2 This volume deals with objections relating primarily or exclusively to policies or proposals relating to the City of Inverness, which are contained in Chapter 2 of the local plan. Objections with a bearing on a number of locations in the City, namely: • the route of Phase V of the Southern Distributor Road • the Cross Rail Link Road; and • objections relating to retailing issues and retail sites are considered in Chapters 6-8 respectively. Thereafter, Chapters 9-21 consider objections following as far as possible the arrangement and order in the plan. Chapter 22 considers housing land supply in the local plan area and the Council’s policy approach to Green Wedges around Inverness. This sets a context for the consideration of objections relating to individual sites promoted for housing, at Chapter 23. CONTENTS VOLUME 2 Abbreviations Introduction Chapter 6 The Southern Distributor Road - Phase V Chapter 7 The Cross Rail Link Road Chapter 8 Retailing Policies and Proposals Chapter 9 Inverness City Centre Chapter 10 Action Areas and the Charleston Expansion Area 10.1 Glenurquhart Road and Rail Yard/College Action Area 10.2 Longman Bay Action Area 10.3 Craig Dunain Action Area and the Charleston Expansion Area 10.4 Ashton Action Area Chapter 11 -

Orcadian Basin Devonian Extensional Tectonics Versus Carboniferous

Journal of the Geological Society Devonian extensional tectonics versus Carboniferous inversion in the northern Orcadian basin M. SERANNE Journal of the Geological Society 1992; v. 149; p. 27-37 doi:10.1144/gsjgs.149.1.0027 Email alerting click here to receive free email alerts when new articles cite this article service Permission click here to seek permission to re-use all or part of this article request Subscribe click here to subscribe to Journal of the Geological Society or the Lyell Collection Notes Downloaded by INIST - CNRS trial access valid until 31/05/2008 on 31 March 2008 © 1992 Geological Society of London Journal of the Geological Society, London, Vol. 149, 1992, pp. 21-31, 14 figs, Printed in Northern Ireland Devonian extensional tectonics versus Carboniferous inversion in the northern Orcadian basin M. SERANNE Laboratoire de Gdologie des Bassins, CNRS u.a.1371, 34095 Montpellier cedex 05, France Abstract: The Old Red Sandstone (Middle Devonian) Orcadian basin was formed as a consequence of extensional collapse of the Caledonian orogen. Onshore study of these collapse-basins in Orkney and Shetland provides directions of extension during basin development. The origin of folding of Old Red Sandstone sediments, that has generally been related to a Carboniferous inversion phase, is discussed: syndepositional deformation supports a Devonian age and consequently some of the folds are related to basin formation. Large-scale folding of Devonian strata results from extensional and left-lateral transcurrent faulting of the underlying basement. Spatial variation of extension direction and distribution of extensional and transcurrent tectonics fit with a model of regional releasing overstep within a left- lateral megashear in NW Europe during late-Caledonian extensional collapse. -

Scottish Photographers NOTES Summer 2010

Scottish Photographers NOTES Summer 2010 Scottish Photographers is a network of independent photographers in Scotland. Scottish Photographers www.scottish-photographers.com Contents [email protected] 3 Editorial Organiser: Carl Radford 15 Pittenweem Path High Blantyre G72 OGZ 4 Andy Biggs: An English River 01698 826414 [email protected] 10 Stefan Serowatka: Northern Grace Editor: Sandy Sharp 33 Avon Street Motherwell ML1 3AA 16 John Kemplay: Shop Windows 01698 262 313 [email protected] 18 Spotlight: Colin Gray Accountant: Stewart Shaw 13 Mount Stuart Street Glasgow G41 3YL 20 Melanie Sims: Memorandum 0141 632 8926 [email protected] 24 At Work: The Photographic Work of Jakob Jakobsson Webmaster: Jamie McAteer 88/4 Craighouse Gardens Edinburgh EH 10 5LW 28 Donald Stewart. Book Review: Tillman Crane Jordan 0797 13792424 [email protected] 30 Michael Thomson: Wind Farms in Inner Mongolia NOTES for Scottish Photographers is published three times a year, in January, May and September. 34 Robin Gillanders on Diane Arbus If a renewal form is enclosed then your annual subscription is 36 The Photographers' Place due. Donations are always welcome. 37 News and Events Individuals £10.00; Concessions £5.00; Overseas £15.00. Front Cover Jakob Jakobsson: Surveyors NOTES for Scottish Photographers Number Twenty Summer 2010 Michael Shulman. This makes us wonder; when is a Scottish Pho- tographer ever going to apply to join Magnum? The last issue of NOTES had an elegaic theme and the work of Melanie Sims continues this. The Park Gallery in Falkirk was the venue for a truly beautiful exhibition which showed work that Mela- nie had been gradually introducing to the Street Level meetings. -

Inverness Active Travel

S e a T h e o ld r n R b d A u n s d h e C R r r d s o o m n d w M S a t e a l o c l l R e R n n d n a n a m C r g Dan Corbett e l P O s n r yvi P s W d d l Gdns o T Maclennan n L e a S r Gdns l e Anderson t Sea ae o l St Ct eld d R L d In ca Citadel Rd L d i o ia a w S m d e t Ja R Clachnacudden r B e K t e S Fire Station n Kilmuir s u Football s s l Ct r o a PUBLIC a i c r Harbour R WHY CHOOSE ACTIVE TRAVEL? k d Harbour Road R u Club ad S d m t M il Roundabout TRANSPORT K t S Cycling is fast and convenient. Pumpgate Lochalsh n Ct Ct o t College H It is often quicker to travel by bike than by bus or Traveline Scotland – s S a r l b o car in the city. Cycle parking is easy and free. www.travelinescotland.com t e n W u r S N w al R o 1 k o r t er a copyright HITRANS – www.scotrail.co.uk d ScotRail e B S Rd H It helps you stay fit and healthy. t Pl a a Shoe Walker rb e d o Ln G r CollegeInverness City Centreu Incorporating exercise into your daily routine helps Stagecoach – www.stagecoachbus.com r R r a Tap n o R mpg Telford t t d you to achieve the recommended 150 minutes of Skinner h t u S – www.decoaches.co.uk t e Visitor information Post oce D and E Coaches Ct P Ave Waterloo S exercise a week which will help keep you mentally n r Upper Kessock St Bridge Longman Citylink – www.citylink.co.ukCa u Museum & art gallery Supermarket and physically healthy. -

Place-Names of Inverness and Surrounding Area Ainmean-Àite Ann an Sgìre Prìomh Bhaile Na Gàidhealtachd

Place-Names of Inverness and Surrounding Area Ainmean-àite ann an sgìre prìomh bhaile na Gàidhealtachd Roddy Maclean Place-Names of Inverness and Surrounding Area Ainmean-àite ann an sgìre prìomh bhaile na Gàidhealtachd Roddy Maclean Author: Roddy Maclean Photography: all images ©Roddy Maclean except cover photo ©Lorne Gill/NatureScot; p3 & p4 ©Somhairle MacDonald; p21 ©Calum Maclean. Maps: all maps reproduced with the permission of the National Library of Scotland https://maps.nls.uk/ except back cover and inside back cover © Ashworth Maps and Interpretation Ltd 2021. Contains Ordnance Survey data © Crown copyright and database right 2021. Design and Layout: Big Apple Graphics Ltd. Print: J Thomson Colour Printers Ltd. © Roddy Maclean 2021. All rights reserved Gu Aonghas Seumas Moireasdan, le gràdh is gean The place-names highlighted in this book can be viewed on an interactive online map - https://tinyurl.com/ybp6fjco Many thanks to Audrey and Tom Daines for creating it. This book is free but we encourage you to give a donation to the conservation charity Trees for Life towards the development of Gaelic interpretation at their new Dundreggan Rewilding Centre. Please visit the JustGiving page: www.justgiving.com/trees-for-life ISBN 978-1-78391-957-4 Published by NatureScot www.nature.scot Tel: 01738 444177 Cover photograph: The mouth of the River Ness – which [email protected] gives the city its name – as seen from the air. Beyond are www.nature.scot Muirtown Basin, Craig Phadrig and the lands of the Aird. Central Inverness from the air, looking towards the Beauly Firth. Above the Ness Islands, looking south down the Great Glen. -

Draft CCC Minutes SEPT 2016

Draft Minutes for approval CREICH COMMUNITY COUNCIL Minutes of meeting held on Tuesday 20th September 2016 at 7.30pm in Rosehall Village Hall Present: Pete Campbell, Chair, (PC), Ron Boothroyd, Vice Chair (RB), Russell Taylor, Treasurer, Also present: Michael Baird (MB), Norman Vincent (NV), Jennifer Munro (JM) Police Scotland: PC Dave Thompson (DT) and PC Chris Wylie (CW) Apologies: Russell Smith (RS), John White (JW), Norman MacDonald (NM), Brian Coghill (BC) and Highland Councillor George Farlow (GF) Secretary: Mary Goulder (MG) Item 1. Welcome/Apologies (as above)/Police report (See below). Pete Campbell welcomed everyone but recorded that the meeting was not quorate due to the apologies received from elected members. It was agreed to conduct the meeting to the best ability of those members present and that no decisions could be taken without the opinions of the others. An email will be circulated after the meeting with any recommendations made to seek approval/rejection as appropriate. MG Action. Item 2. Minutes of August meeting/matters arising (if not on agenda). The minutes of the August meeting were approved, as a true and accurate record; proposed: Russell Taylor, seconded: Ron Boothroyd. (1) Invitation to THC Roads Manager and Police Scotland Area Commander. This is proposed for the October CC meeting (18th) and invitations will be issued. MG Action. From the floor NV asked to register is complaint that since he raised the traffic issues in Bonar at the June meeting, to date no action has been taken by the CC. Chair advised that had been agreed at the last meeting that the North Area Commander Police Scotland and the Head of Roads at Highland Council would be invited to attend the October meeting.