Orkney and Shetland

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Alexander the Great's Tombolos at Tyre and Alexandria, Eastern Mediterranean ⁎ N

Available online at www.sciencedirect.com Geomorphology 100 (2008) 377–400 www.elsevier.com/locate/geomorph Alexander the Great's tombolos at Tyre and Alexandria, eastern Mediterranean ⁎ N. Marriner a, , J.P. Goiran b, C. Morhange a a CNRS CEREGE UMR 6635, Université Aix-Marseille, Europôle de l'Arbois, BP 80, 13545 Aix-en-Provence cedex 04, France b CNRS MOM Archéorient UMR 5133, 5/7 rue Raulin, 69365 Lyon cedex 07, France Received 25 July 2007; received in revised form 10 January 2008; accepted 11 January 2008 Available online 2 February 2008 Abstract Tyre and Alexandria's coastlines are today characterised by wave-dominated tombolos, peculiar sand isthmuses that link former islands to the adjacent continent. Paradoxically, despite a long history of inquiry into spit and barrier formation, understanding of the dynamics and sedimentary history of tombolos over the Holocene timescale is poor. At Tyre and Alexandria we demonstrate that these rare coastal features are the heritage of a long history of natural morphodynamic forcing and human impacts. In 332 BC, following a protracted seven-month siege of the city, Alexander the Great's engineers cleverly exploited a shallow sublittoral sand bank to seize the island fortress; Tyre's causeway served as a prototype for Alexandria's Heptastadium built a few months later. We report stratigraphic and geomorphological data from the two sand spits, proposing a chronostratigraphic model of tombolo evolution. © 2008 Elsevier B.V. All rights reserved. Keywords: Tombolo; Spit; Tyre; Alexandria; Mediterranean; Holocene 1. Introduction Courtaud, 2000; Browder and McNinch, 2006); (2) establishing a typology of shoreline salients and tombolos (Zenkovich, 1967; The term tombolo is used to define a spit of sand or shingle Sanderson and Eliot, 1996); and (3) modelling the geometrical linking an island to the adjacent coast. -

Scapa Flow Scale Site Environmental Description 2019

Scapa Flow Scale Test Site – Environmental Description January 2019 Uncontrolled when printed Document History Revision Date Description Originated Reviewed Approved by by by 0.1 June 2010 Initial client accepted Xodus LF JN version of document Aurora 0.2 April 2011 Inclusion of baseline wildlife DC JN JN monitoring data 01 Dec 2013 First registered version DC JN JN 02 Jan 2019 Update of references and TJ CL CL document information Disclaimer In no event will the European Marine Energy Centre Ltd or its employees or agents, be liable to you or anyone else for any decision made or action taken in reliance on the information in this report or for any consequential, special or similar damages, even if advised of the possibility of such damages. While we have made every attempt to ensure that the information contained in the report has been obtained from reliable sources, neither the authors nor the European Marine Energy Centre Ltd accept any responsibility for and exclude all liability for damages and loss in connection with the use of the information or expressions of opinion that are contained in this report, including but not limited to any errors, inaccuracies, omissions and misleading or defamatory statements, whether direct or indirect or consequential. Whilst we believe the contents to be true and accurate as at the date of writing, we can give no assurances or warranty regarding the accuracy, currency or applicability of any of the content in relation to specific situations or particular circumstances. Title: Scapa Flow Scale Test -

CNPA.Paper.5102.Plan

Cairngorms National Park Energy Options Appraisal Study Final Report for Cairngorms National Park Authority Prepared for: Cairngorms National Park Authority Prepared by: SAC Consulting: Environment & Design Checked by: Henry Collin Date: 14 December 2011 Certificate FS 94274 Certificate EMS 561094 ISO 9001:2008 ISO 14001:2004 Cairngorms National Park Energy Options Appraisal Study Contents 1 Introduction .............................................................................................................................. 1 1.1 Brief .................................................................................................................................. 1 1.2 Policy Context ................................................................................................................... 1 1.3 Approach .......................................................................................................................... 3 1.4 Structure of this Report ..................................................................................................... 4 2 National Park Context .............................................................................................................. 6 2.1 Introduction ....................................................................................................................... 6 2.2 Socio Economic Profile ..................................................................................................... 6 2.3 Overview of Environmental Constraints ......................................................................... -

Results of the Seabird 2000 Census – Great Skua

July 2011 THE DATA AND MAPS PRESENTED IN THESE PAGES WAS INITIALLY PUBLISHED IN SEABIRD POPULATIONS OF BRITAIN AND IRELAND: RESULTS OF THE SEABIRD 2000 CENSUS (1998-2002). The full citation for the above publication is:- P. Ian Mitchell, Stephen F. Newton, Norman Ratcliffe and Timothy E. Dunn (Eds.). 2004. Seabird Populations of Britain and Ireland: results of the Seabird 2000 census (1998-2002). Published by T and A.D. Poyser, London. More information on the seabirds of Britain and Ireland can be accessed via http://www.jncc.defra.gov.uk/page-1530. To find out more about JNCC visit http://www.jncc.defra.gov.uk/page-1729. Table 1a Numbers of breeding Great Skuas (AOT) in Scotland and Ireland 1969–2002. Administrative area Operation Seafarer SCR Census Seabird 2000 Percentage Percentage or country (1969–70) (1985–88) (1998–2002) change since change since Seafarer SCR Shetland 2,968 5,447 6,846 131% 26% Orkney 88 2,0001 2,209 2410% 10% Western Isles– 19 113 345 1716% 205% Comhairle nan eilean Caithness 0 2 5 150% Sutherland 4 82 216 5300% 163% Ross & Cromarty 0 1 8 700% Lochaber 0 0 2 Argyll & Bute 0 0 3 Scotland Total 3,079 7,645 9,634 213% 26% Co. Mayo 0 0 1 Ireland Total 0 0 1 Britain and Ireland Total 3,079 7,645 9,635 213% 26% Note 1 Extrapolated from a count of 1,652 AOT in 1982 (Meek et al., 1985) using previous trend data (Furness, 1986) to estimate numbers in 1986 (see Lloyd et al., 1991). -

Shetland Mainland North (Potentially Vulnerable Area 04/01)

Shetland Mainland North (Potentially Vulnerable Area 04/01) Local Plan District Local authority Main catchment Shetland Shetland Islands Council Shetland coastal Summary of flooding impacts Summary of flooding impacts flooding of Summary At risk of flooding • <10 residential properties • <10 non-residential properties • £47,000 Annual Average Damages (damages by flood source shown left) Summary of objectives to manage flooding Objectives have been set by SEPA and agreed with flood risk management authorities. These are the aims for managing local flood risk. The objectives have been grouped in three main ways: by reducing risk, avoiding increasing risk or accepting risk by maintaining current levels of management. Objectives Many organisations, such as Scottish Water and energy companies, actively maintain and manage their own assets including their risk from flooding. Where known, these actions are described here. Scottish Natural Heritage and Historic Environment Scotland work with site owners to manage flooding where appropriate at designated environmental and/or cultural heritage sites. These actions are not detailed further in the Flood Risk Management Strategies. Summary of actions to manage flooding The actions below have been selected to manage flood risk. Flood Natural flood New flood Community Property level Site protection protection management warning flood action protection plans scheme/works works groups scheme Actions Flood Natural flood Maintain flood Awareness Surface water Emergency protection management warning raising plan/study plans/response study study Maintain flood Strategic Flood Planning Self help Maintenance protection mapping and forecasting policies scheme modelling Shetland Local Plan District Section 2 20 Shetland Mainland North (Potentially Vulnerable Area 04/01) Local Plan District Local authority Main catchment Shetland Shetland Islands Council Shetland coastal Background This Potentially Vulnerable Area is There are several communities located in the north of Mainland including Voe, Mossbank, Brae and Shetland (shown below). -

CAIRNGORMS NATIONAL PARK / TROSSACHS NATIONAL PARK Wildlife Guide How Many of These Have You Spotted in the Forest?

CAIRNGORMS NATIONAL PARK / TROSSACHS NATIONAL PARK Wildlife GuidE How many of these have you spotted in the forest? SPECIES CAIRNGORMS NATIONAL PARK Capercaillie The turkey-sized Capercaillie is one of Scotland’s most characteristic birds, with 80% of the UK's species living in Cairngorms National Park. Males are a fantastic sight to behold with slate-grey plumage, a blue sheen over the head, neck and breast, reddish-brown upper wings with a prominent white shoulder flash, a bright red eye ring, and long tail. Best time to see Capercaille: April-May at Cairngorms National Park Pine Marten Pine martens are cat sized members of the weasel family with long bodies (65-70 cm) covered with dark brown fur with a large creamy white throat patch. Pine martens have a distinctive bouncing run when on the ground, moving front feet and rear feet together, and may stop and stand upright on their haunches to get a better view. Best time to see Pine Martens: June-September at Cairngorms National Park Golden Eagle Most of the Cairngorm mountains have just been declared as an area that is of European importance for the golden eagle. If you spend time in the uplands and keep looking up to the skies you may be lucky enough to see this great bird soaring around ridgelines, catching the thermals and looking for prey. Best time to see Golden Eagles: June-September in Aviemore Badger Badgers are still found throughout Scotland often in surprising numbers. Look out for the signs when you are walking in the countryside such as their distinctive paw prints in mud and scuffles where they have snuffled through the grass. -

Where to Go: Puffin Colonies in Ireland Over 15,000 Puffin Pairs Were Recorded in Ireland at the Time of the Last Census

Where to go: puffin colonies in Ireland Over 15,000 puffin pairs were recorded in Ireland at the time of the last census. We are interested in receiving your photos from ANY colony and the grid references for known puffin locations are given in the table. The largest and most accessible colonies here are Great Skellig and Great Saltee. Start Number Site Access for Pufferazzi Further information Grid of pairs Access possible for Puffarazzi, but Great Skellig V247607 4,000 worldheritageireland.ie/skellig-michael check local access arrangements Puffin Island - Kerry V336674 3,000 Access more difficult Boat trips available but landing not possible 1,522 Access possible for Puffarazzi, but Great Saltee X950970 salteeislands.info check local access arrangements Mayo Islands l550938 1,500 Access more difficult Illanmaster F930427 1,355 Access more difficult Access possible for Puffarazzi, but Cliffs of Moher, SPA R034913 1,075 check local access arrangements Stags of Broadhaven F840480 1,000 Access more difficult Tory Island and Bloody B878455 894 Access more difficult Foreland Kid Island F785435 370 Access more difficult Little Saltee - Wexford X968994 300 Access more difficult Inishvickillane V208917 170 Access more difficult Access possible for Puffarazzi, but Horn Head C005413 150 check local access arrangements Lambay Island O316514 87 Access more difficult Pig Island F880437 85 Access more difficult Inishturk Island L594748 80 Access more difficult Clare Island L652856 25 Access more difficult Beldog Harbour to Kid F785435 21 Access more difficult Island Mayo: North West F483156 7 Access more difficult Islands Ireland’s Eye O285414 4 Access more difficult Howth Head O299389 2 Access more difficult Wicklow Head T344925 1 Access more difficult Where to go: puffin colonies in Inner Hebrides Over 2,000 puffin pairs were recorded in the Inner Hebrides at the time of the last census. -

Ferry Timetables

1768 Appendix 1. www.orkneyferries.co.uk GRAEMSAY AND HOY (MOANESS) EFFECTIVE FROM 24 SEPTEMBER 2018 UNTIL 4 MAY 2019 Our service from Stromness to Hoy/Graemsay is a PASSENGER ONLY service. Vehicles can be carried by prior arrangement to Graemsay on the advertised cargo sailings. Monday Tuesday Wednesday Thursday Friday Saturday Sunday Stromness dep 0745 0745 0745 0745 0745 0930 0930 Hoy (Moaness) dep 0810 0810 0810 0810 0810 1000 1000 Graemsay dep 0825 0825 0825 0825 0825 1015 1015 Stromness dep 1000 1000 1000 1000 1000 Hoy (Moaness) dep 1030 1030 1030 1030 1030 Graemsay dep 1045 1045 1045 1045 1045 Stromness dep 1200A 1200A 1200A Graemsay dep 1230A 1230A 1230A Hoy (Moaness) dep 1240A 1240A 1240A Stromness dep 1600 1600 1600 1600 1600 1600 1600 Graemsay dep 1615 1615 1615 1615 1615 1615 1615 Hoy (Moaness) dep 1630 1630 1630 1630 1630 1630 1630 Stromness dep 1745 1745 1745 1745 1745 Graemsay dep 1800 1800 1800 1800 1800 Hoy (Moaness) dep 1815 1815 1815 1815 1815 Stromness dep 2130 Graemsay dep 2145 Hoy (Moaness) dep 2200 A Cargo Sailings will have limitations on passenger numbers therefore booking is advisable. These sailings may be delayed due to cargo operations. Notes: 1. All enquires must be made through the Kirkwall Office. Telephone: 01856 872044. 2. Passengers are requested to be available for boarding 5 minutes before departure. 3. Monday cargo to be booked by 1600hrs on previous Friday otherwise all cargo must be booked before 1600hrs the day before sailing. Cargo must be delivered to Stromness Pier no later than 1100hrs on the day of sailing. -

Northmavine the Laird’S Room at the Tangwick Haa Museum Tom Anderson

Northmavine The Laird’s room at the Tangwick Haa Museum Tom Anderson Tangwick Haa All aspects of life in Northmavine over the years are Northmavine The wilds of the North well illustrated in the displays at Tangwick Haa Museum at Eshaness. The Haa was built in the late 17th century for the Cheyne family, lairds of the Tangwick Estate and elsewhere in Shetland. Some Useful Information Johnnie Notions Accommodation: VisitShetland, Lerwick, John Williamson of Hamnavoe, known as Tel:01595 693434 Johnnie Notions for his inventive mind, was one of Braewick Caravan Park, Northmavine’s great characters. Though uneducated, Eshaness, Tel 01806 503345 he designed his own inoculation against smallpox, Neighbourhood saving thousands of local people from this 18th Information Point: Tangwick Haa Museum, Eshaness century scourge of Shetland, without losing a single Shops: Hillswick, Ollaberry patient. Fuel: Ollaberry Public Toilets: Hillswick, Ollaberry, Eshaness Tom Anderson Places to Eat: Hillswick, Eshaness Another famous son of Northmavine was Dr Tom Post Offices: Hillswick, Ollaberry Anderson MBE. A prolific composer of fiddle tunes Public Telephones: Sullom, Ollaberry, Leon, and a superb player, he is perhaps best remembered North Roe, Hillswick, Urafirth, for his work in teaching young fiddlers and for his role Eshaness in preserving Shetland’s musical heritage. He was Churches: Sullom, Hillswick, North Roe, awarded an honorary doctorate from Stirling Ollaberry University for his efforts in this field. Doctor: Hillswick, Tel: 01806 503277 Police Station: Brae, Tel: 01806 522381 The camping böd which now stands where Johnnie Notions once lived Contents copyright protected - please contact Shetland Amenity Trust for details. Whilst every effort has been made to ensure the contents are accurate, the funding partners do not accept responsibility for any errors in this leaflet. -

Layout 1 Copy

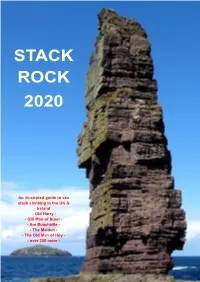

STACK ROCK 2020 An illustrated guide to sea stack climbing in the UK & Ireland - Old Harry - - Old Man of Stoer - - Am Buachaille - - The Maiden - - The Old Man of Hoy - - over 200 more - Edition I - version 1 - 13th March 1994. Web Edition - version 1 - December 1996. Web Edition - version 2 - January 1998. Edition 2 - version 3 - January 2002. Edition 3 - version 1 - May 2019. Edition 4 - version 1 - January 2020. Compiler Chris Mellor, 4 Barnfield Avenue, Shirley, Croydon, Surrey, CR0 8SE. Tel: 0208 662 1176 – E-mail: [email protected]. Send in amendments, corrections and queries by e-mail. ISBN - 1-899098-05-4 Acknowledgements Denis Crampton for enduring several discussions in which the concept of this book was developed. Also Duncan Hornby for information on Dorset’s Old Harry stacks and Mick Fowler for much help with some of his southern and northern stack attacks. Mike Vetterlein contributed indirectly as have Rick Cummins of Rock Addiction, Rab Anderson and Bruce Kerr. Andy Long from Lerwick, Shetland. has contributed directly with a lot of the hard information about Shetland. Thanks are also due to Margaret of the Alpine Club library for assistance in looking up old journals. In late 1996 Ben Linton, Ed Lynch-Bell and Ian Brodrick undertook the mammoth scanning and OCR exercise needed to transfer the paper text back into computer form after the original electronic version was lost in a disk crash. This was done in order to create a world-wide web version of the guide. Mike Caine of the Manx Fell and Rock Club then helped with route information from his Manx climbing web site. -

Annual Shetland Pony Sale – Lerwick 2011

ANNUAL SHETLAND PONY SALE – LERWICK 2011 Shetland’s annual show and sale of Shetland Ponies was held on Thursday 6th and Friday 7th October 2011 at the Shetland Rural Centre, Lerwick. Entries for the sale were down on previous years with 133 ponies entered in this year’s catalogue. In particular there were fewer colt foals and fillies entered than usual meaning that the majority of ponies offered for sale were filly foals. Top price at the sale went to Mrs L J Burgess for her standard piebald filly foal, Robin’s Brae Pippa by HRE Fetlar, which realised 600 gns to A A Robertson, Walls, Shetland. HRE Fetlar achieved a gold award in the Pony Breeders of Shetland Association Shetland Pony Evaluation Scheme. The champion filly foal from the previous day’s show, Mrs M Inkster’s standard black filly, Laurenlea Louise by Birchwood Pippin, sold at 475 gns to Miss P J J Gear, Foula. Champion colt foal Niko of Kirkatown by Loanin Cleon, from Mr D A Laurenson, Haroldswick sold for 10 gns to Claire Smith, Punds, Sandwick. Regrettably, demand and prices in general were poor and some ponies passed through the ring unsold. Local sales accounted for a good proportion of trade as did the support of the regular buyers that make the annual trip from mainland UK to attend the sale each year. The show of foals on Thursday evening was judged by Mr Holder Firth, Eastaben, Orkney and his prizewinners and the prices that they realised, if sold, were as follows: Standard Black Filly Foals Gns 1st Laurenlea Louise Mrs M Inkster, Haroldswick, Unst 475 2nd Robin’s -

Cetaceans of Shetland Waters

CETACEANS OF SHETLAND The cetacean fauna (whales, dolphins and porpoises) of the Shetland Islands is one of the richest in the UK. Favoured localities for cetaceans are off headlands and between sounds of islands in inshore areas, or over fishing banks in offshore regions. Since 1980, eighteen species of cetacean have been recorded along the coast or in nearshore waters (within 60 km of the coast). Of these, eight species (29% of the UK cetacean fauna) are either present throughout the year or recorded annually as seasonal visitors. Of recent unusual live sightings, a fin whale was observed off the east coast of Noss on 11th August 1994; a sei whale was seen, along with two minkes whales, off Muckle Skerry, Out Skerries on 27th August 1993; 12-14 sperm whales were seen on 14th July 1998, 14 miles south of Sumburgh Head in the Fair Isle Channel; single belugas were seen on 4th January 1996 in Hoswick Bay and on 18th August 1997 at Lund, Unst; and a striped dolphin came into Tresta Voe on 14th July 1993, eventually stranding, where it was euthanased. CETACEAN SPECIES REGULARLY SIGHTED IN THE REGION Humpback whale Megaptera novaeangliae Since 1992, humpback whales have been seen annually off the Shetland coast, with 1-3 individuals per year. The species was exploited during the early part of the century by commercial whaling and became very rare for over half a century. Sightings generally occur between May-September, particularly in June and July, mainly around the southern tip of Shetland. Minke whale Balaenoptera acutorostrata The minke whale is the most commonly sighted whale in Shetland waters.