Nance Corporation and PSFS 3 Corporation on the Duugular Issue

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Contribution of the Leg Club Model of Care to the Well-Being of People Living with Chronic Wounds

research Contribution of the Leg Club model of care to the well-being of people living with chronic wounds l Objective: Social support impacts well-being. Higher levels of social support encourage treatment adherence and aid healing in people living with chronic wounds. The Leg Club model of care harnesses social support mechanisms to improve patient outcomes. This study investigated whether social support mechanisms available through a Leg Club environment influenced well-being. l Method: Participants were community Leg Club members. Socio-demographic data was collected, and the Well-being in Wounds Inventory (WOWI) administered to assess ‘wound worries,’ ‘personal resources,’ and ‘well-being’. Participants’ perceived social situation, length of time attending a Leg Club, wound duration, and feelings about their physical appearance were also measured. l Results: The subjects recruited (n=49) were aged between 50 and 94 years (mean=75.34, standard deviation=10.31). Membership of a Leg Club did impact well-being factors. Time spent at a Leg Club improved ‘personal resources’ over time. ‘Perceived social situation’ predicted key aspects of well-being, as did ‘time spent attending a Leg Club’ and ‘feelings about physical appearance.’ Social support and relief from social isolation were important aspects of Leg Club membership for participants. l Conclusion: Attending a Leg Club enhances well-being in people living with a chronic wound; social support has an important role to play in this relationship. Future research should consider the specific interplay of social support mechanisms of Leg Club, and other relevant wound-related variables to optimise patient well-being and treatment outcomes. -

Harpercollins Books for the First-Year Student

S t u d e n t Featured Titles • American History and Society • Food, Health, and the Environment • World Issues • Memoir/World Views • Memoir/ American Voices • World Fiction • Fiction • Classic Fiction • Religion • Orientation Resources • Inspiration/Self-Help • Study Resources www.HarperAcademic.com Index View Print Exit Books for t H e f i r s t - Y e A r s t u d e n t • • 1 FEATURED TITLES The Boy Who Harnessed A Pearl In the Storm the Wind How i found My Heart in tHe Middle of tHe Ocean Creating Currents of eleCtriCity and Hope tori Murden McClure William kamkwamba & Bryan Mealer During June 1998, Tori Murden McClure set out to William Kamkwamba was born in Malawi, Africa, a row across the Atlantic Ocean by herself in a twenty- country plagued by AIDS and poverty. When, in three-foot plywood boat with no motor or sail. 2002, Malawi experienced their worst famine in 50 Within days she lost all communication with shore, years, fourteen-year-old William was forced to drop ultimately losing updates on the location of the Gulf out of school because his family could not afford the Stream and on the weather. In deep solitude and $80-a-year-tuition. However, he continued to think, perilous conditions, she was nonetheless learn, and dream. Armed with curiosity, determined to prove what one person with a mission determination, and a few old science textbooks he could do. When she was finally brought to her knees discovered in a nearby library, he embarked on a by a series of violent storms that nearly killed her, daring plan to build a windmill that could bring his she had to signal for help and go home in what felt family the electricity only two percent of Malawians like complete disgrace. -

Walpole Public Library DVD List A

Walpole Public Library DVD List [Items purchased to present*] Last updated: 9/17/2021 INDEX Note: List does not reflect items lost or removed from collection A B C D E F G H I J K L M N O P Q R S T U V W X Y Z Nonfiction A A A place in the sun AAL Aaltra AAR Aardvark The best of Bud Abbot and Lou Costello : the Franchise Collection, ABB V.1 vol.1 The best of Bud Abbot and Lou Costello : the Franchise Collection, ABB V.2 vol.2 The best of Bud Abbot and Lou Costello : the Franchise Collection, ABB V.3 vol.3 The best of Bud Abbot and Lou Costello : the Franchise Collection, ABB V.4 vol.4 ABE Aberdeen ABO About a boy ABO About Elly ABO About Schmidt ABO About time ABO Above the rim ABR Abraham Lincoln vampire hunter ABS Absolutely anything ABS Absolutely fabulous : the movie ACC Acceptable risk ACC Accepted ACC Accountant, The ACC SER. Accused : series 1 & 2 1 & 2 ACE Ace in the hole ACE Ace Ventura pet detective ACR Across the universe ACT Act of valor ACT Acts of vengeance ADA Adam's apples ADA Adams chronicles, The ADA Adam ADA Adam’s Rib ADA Adaptation ADA Ad Astra ADJ Adjustment Bureau, The *does not reflect missing materials or those being mended Walpole Public Library DVD List [Items purchased to present*] ADM Admission ADO Adopt a highway ADR Adrift ADU Adult world ADV Adventure of Sherlock Holmes’ smarter brother, The ADV The adventures of Baron Munchausen ADV Adverse AEO Aeon Flux AFF SEAS.1 Affair, The : season 1 AFF SEAS.2 Affair, The : season 2 AFF SEAS.3 Affair, The : season 3 AFF SEAS.4 Affair, The : season 4 AFF SEAS.5 Affair, -

Not Everything Has Changed REPORT to STAKEHOLDERS, MAY–AUGUST, 2017 Not Everything Has Changed

Not Everything Has Changed REPORT TO STAKEHOLDERS, MAY–AUGUST, 2017 Not Everything Has Changed Much has changed since Election Day, November 8, including at ProPublica. We added new beats on immigration, the President’s personal business interests, white supremacy and hate crimes, extra reporting firepower on environmental issues, and much more—not to mention extensive coverage of the new administration, much of it focused on transparency. But the need for the deep-dive investigative report- Renee Montagne. It takes an unsparing look at why ing for which ProPublica is best known remains as the U.S. has the highest maternal death rate in the de- critical as it has ever been. In a short attention-span veloped world. Every year, 700 to 900 American wom- world, in an atmosphere of politics that sometimes en die from pregnancy or childbirth-related causes seems divorced from policy, in a news ecosystem of- (with 60 percent of these deaths being preventable), ten addicted to quick clicks, shallow answers and an and some 65,000 women come very close to dying. absence of context, ProPublica proudly marches to a And while maternal mortality has declined signifi- different drummer. cantly in other wealthy countries in recent years, it is Over the middle period of 2017, ProPublica took on rising in the U.S. stories that other news organizations would pass on as After launching the series with the harrowing being too complex, time-consuming or legally risky. story of Lauren Bloomstein, a neonatal nurse who This kind of journalism is an essential and effective died in childbirth in the hospital where she worked weapon against abuses of power and betrayals of the — of preeclampsia, a preventable type of high blood public trust. -

MY FATHER's HOUSE a Modesto Tragedy a Play in Three Acts by Ken White

MY FATHER'S HOUSE A Modesto Tragedy A Play in Three Acts by Ken White (Inspired by Actual Events) Ken White 1108 Wellesley Avenue Modesto, CA 95350-5044 (209) 567-0600 [email protected] Cast of Characters (In Order of Appearance) DOCTOR GUITAR, 32, street musician and high school classmate of MIKE PROKES. MIKE PROKES, 31, public relations man for Peoples Temple. JAMES WARREN JONES, 47, Founder and Pastor of Peoples Temple. THE VIETNAM VET, 30, a white male Jonestown survivor. THE ARTIST, 20, a white female Jonestown survivor. THE TV REPORTER, 32, a female journalist for NBC News. THE NEWSPAPER REPORTER, 35, a male journalist for The Modesto Bee. THE GRANDMOTHER of a Jonestown victim, 50-something African-American. THE GRANDFATHER of a Jonestown victim, 50-something African-American. THE BLIND BEGGAR, 40, an African-American female Jonestown survivor. THE TEACHER, 36, a white male high school government teacher. THE FRIEND, 31, a white male childhood friend and college roommate of PROKES. THE COLLEGE STUDENT, 19, a male Modesto Junior College student and reporter for The Pirates' Log. THE OLD FLAME, 31, a white female high school sweetheart of PROKES. MARY PROKES, 50, a housewife and the mother of PROKES. THOMAS PROKES, 50, a plant manager and the father of PROKES. THE PUNK, 31, a white male high school classmate of PROKES. JIM JON (KIMO) PROKES, 4, the stepson of PROKES. THE MENTOR, 43, a white male news anchor for KXTV, Channel 10. 1 Time The play begins on Thursday, March 8th, 1979, and ends the following Tuesday night, March 13th, 1979. -

Actor - Female

Actor - Female Julia Davis - Fear Of Fanny BBC Drama for BBC Four Susan Lynch - Soundproof BBC Drama in association with Blast! Films for BBC Two Helen Mirren - Prime Suspect ITV Productions for ITV Actor - Male Jim Broadbent - Longford A Granada Production for Channel 4 in association with HBO Films Philip Glenister - Life On Mars BBC/Kudos Film and Television for BBC One Michael Sheen - Kenneth Williams: Fantabulosa! BBC Drama for BBC Four Arts 9/11: Out Of The Blue Silver River Productions for five Peter And The Wolf BreakThru Films for Channel 4 Simon Schama's Power Of Art: Bernini BBC London Arts for BBC Two Breakthrough Award - Behind the Screen Lisa Gilchrist (Producer) - See No Evil: The Moors Murders ITV Productions for ITV Bart Layton (Producer/Director) - Banged Up Abroad Raw TV for five Lee Mack & Andrew Collins (Writers) - Not Going Out Avalon Television for BBC One Breakthrough Award - On Screen Sacha Dhawan - Bradford Riots An Oxford Film and Television Production in association with Great Meadow Productions for Channel 4 Joseph Mawle - Soundproof BBC Drama in association with Blast! Films for BBC Two Russell Brand - Russell Brand's Got Issues Vanity Productions for Channel 4 Children's Drama Jackanory: Muddle Earth CBBC That Summer Day Hat Trick Productions for CBBC Young Dracula CBBC Children's Programme Charlie and Lola: Welcome To Lolaland Tiger Aspect Productions for CBeebies Evacuation Twenty Twenty Productions for CBBC Newsround - The Wrong Trainers BBC for BBC One/Interactive Comedy Performance Kevin Bishop - Star -

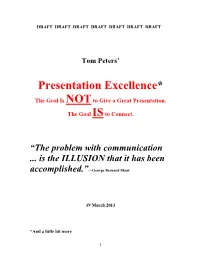

Presentation Excellence* the Goal Is NOT to Give a Great Presentation

DRAFT DRAFT DRAFT DRAFT DRAFT DRAFT DRAFT Tom Peters’ Presentation Excellence* The Goal Is NOT to Give a Great Presentation. The Goal IS to Connect. “The problem with communication ... is the ILLUSION that it has been —George Bernard Shaw accomplished.” 19 March 2013 *And a little bit more 1 Presentation Excellence “The problem with communication ... is the ILLUSION that it has been accomplished.”—George Bernard Shaw I’ve given a tankload of speeches—about 3,000. I suppose I’ve learned a little bit along the way. But what follows is both limited and idiosyncratic. The New York Times’ great reporter-editorialist Johnny Apple wrote a book titled Johnny Apple’s Europe. It was a tour guide that wasn’t a tour guide. That is, it was simply and solely about places he loved in Europe; hence, unabashedly idiosyncratic and not comprehensive in any way, shape or form. This essay is of the same character. It’s about how I give a speech, period. And, moreover, how I give a public speech. Though I think a fair share of it’s universal, the discussion is a long way from “How to give a pitch to a Board of Directors,” or some such. So, then, the message is: Take it for what it’s worth, please, no more and perhaps no less. I’ll begin by giving away my one-and-only “secret,” followed by my other one-and-only “secret,” then that idiosyncratic list of thoughts—139 to be exact.* The One Big Secret: Presentation As Intimate Conversation An effective speech to 5,000 people is an intimate, 1-on-1 conversation! Keep that in mind. -

2017 ANNUAL REPORT the Next Frontier Is Local Propublica Staff Reacts to Our Receiving the Pulitzer Gold Medal for Public Service, April 10, 2017

2017 ANNUAL REPORT The Next Frontier Is Local ProPublica staff reacts to our receiving the Pulitzer gold medal for Public Service, April 10, 2017. (Demetrius Freeman for ProPublica) Highlights of the Year at ProPublica Impact 2017 was a dramatic year for real-world change spurred by our work. Pro- Publica’s journalism fueled reform across the U.S., including the halting of several Facebook practices that facilitated racial discrimination and hate speech; the full pardon of a wrongfully convicted man; steps to address government conflicts of interest, from resignations to congres- sional calls for oversight; the passage of the nation’s first law to tackle al- gorithmic discrimination; and legal protection of workers’ comp benefits for undocumented immigrants. Memorable Our work unmasked secretive deregulation teams with industry ties that President Donald Trump installed across the federal government, and stories told heartbreaking stories of the maternal mortality crisis in the U.S. We revealed abusive federal land seizures in the building of a fence along the U.S.-Mexico border and bankruptcy practices that have kept generations of African Americans in debt. Our reporting unearthed the tragic story of a drug cartel’s deadly assault on a Mexican town (and the failed DEA operation that triggered it) and spotlighted communities nationwide contaminated with toxic waste from military operations. Cover: ProPublica Illinois reporter Duaa Eldeib, left, interviews a public defender in Harrisburg, Ilinois, where almost a dozen young men now face sentences in adult prison. (Nick Schnelle for ProPublica Illinois) PROPUBLICA 2017 ANNUAL REPORT 1 ProPublica Illinois, our first regional publishing operation, launched with a dedicated staff in October. -

The Lamar Seed Company

let me say, neighbor- nau a sab. that the men who built Damory Court hood is not splendid of art.” unaware of the sense of beauty and generosity which le responsible for share deviltry, too.” “And their of the present lack of which you speak.” put In the doctor. Valiant put out his hand with a “I suppose so.” admitted his host. little gesture of deprecation, but the “At this distance I can bear even that. disregarded deeply other it. "Confound It, Company But good or bad. I’m thankful ¦ah, it was to expected of Seed Virginia. be a Va- The Lamar that they chose Since I’ve liant. ancestors wrote browsing in Your their been laid up. I’ve been the names capital —’’ in letters over this library here country. They were an up and down “A bit out of date now\ I reckon.” lot, but good or bad (and, as Southall said the major, ‘but it used to pass says, nodded toward the grandfather was some- I reckon” —he muster. Your great portrait above the oouch —“they & thing of a book-worm. He wrote a weren't all little woolly lambs) they WOOD history of the family, didn’t lie?” did big things in a big way.” COAL it. The Valiants “Yes. I’ve found Valiant leaned forward eagerly, a of Virginia.’ I’m reading the Revolu- question on his lips. But at the mo- Canon City Lump and Nut, Camer- tionary chapters now. It never seemed ment a diversion occurred In the real before —it’s been only a slice of shape of Uncle Jefferson, who re-en- history. -

Fuller at Fox

FULLER AT FOX The first sentence in Samuel Fuller’s Wikipe- excellent music. In order of their appearance Fuller assembled a first-rate cast, including dia entry reads thusly: “Samuel Michael Fuller on these two CDs, they are: Richard Widmark (with whom he’d just worked (August 12, 1912 – October 30, 1997) was on Pickup on South Street), Victor Francen, an American screenwriter, novelist, and film HELL AND HIGH WATER Cameron Mitchell, David Wayne, Gene Evans, director known for low-budget, understated Richard Loo, and, as Denise Girard, newcomer genre movies with controversial themes.” One When Zanuck proposed to Fuller that his next Bella Darvi, who also just happened to be the wonders if the author of that first sentence has project after Pickup on South Street should mistress of Daryl F. Zanuck. The film’s hand- actually seen a Samuel Fuller movie, because be Hell and High Water, Fuller agreed, even some photography was by Joseph MacDonald “understated” would be about the last word though he wasn’t crazy about the script. He did and the music was by Alfred Newman, the you’d ever use about a Fuller film. After all, it as a favor to Zanuck, who’d defended Fuller head of the Fox music department, who by the according to Fuller, he didn’t speak until he when J. Edgar Hoover attacked both Fuller time of Hell and High Water had already won was almost five years old, and when he finally and Fox over Pickup on South Street, about six Oscars. did speak the first word out of his mouth was which more later. -

P Olytechnic

ly. April 2. 1954 Friday, AprU 2, 1954 THE PORT WEEKLY Page Three able. After cutting her teeth, she Mystery Baby developed a passion for chocolate Port High's Quotes Port Washington s cookies. Give me the room whose every Most kindly remembered of her nook is dedicated to a book. My Social Beat childhood accidents was the — Frank Dempster Sherman L5 spraining of both wrists, caused by Sergeant Week-end by her initial attempt at ski Order and simplification are ry Club jumping. This misfortune ex• the first steps toward the mastery "B-r-r-i-n-g" the telephone rang. I answered it and heard a y held first meet- cused her from all her final ex• of a subject. The actual enemy is voice say, "Sergeant, there is a 3gy Club, officers ams. the unknown. war going on at the PDSHS gym. id activity plans Blue is our baby's favorite col• —Thomas Mann or, and her food tastes now lean We need your help." The officers are A teacher effects eternity: he toward Italian dishes. She enjoys Then I donned the traditional , president; Hea- can never tell where his influ• attending dog shows, and "The blue and white and carried a ;-president; Mar- ence stops. Garry Moore Show" is her fa• black flag for the losers in my t, secretary: and —Henry Brooks Adams reasurer. vorite T.V. entertainment. pocket. As I arrived in my trus• of the club will Although our baby lacks a car, ty jalopy, I heard horrible 1 projects that she has managed to travel far Cinemascope screams coming from the gym, on at designated and wide. -

Open House and Give the Coalition’S 9-1- the Event

Active Shooter Mechanism Of Injury NAVIGATOR 2013 Assailant kills two at MOI key to determining Welcome to the busy shopping mall likely internal injuries kingdom of dispatch The International Academies of Emergency Dispatch March | April 2013 THEJOURNAL JOURNALOF EMERGENCY DISPATCH SANDY taKES EAST BY STORM Calls swamp lines iaedjournal.org INSIDE the g columns 5 | Dear Reader JOURNAL 6 | President’s Message | march·APRIL 2013 | VOL. 15 NO. 2 7 Ask Doc 8 | Academy Research 9 | Police Beat 10 | Leadership Lingo 44 | Retro Space 56 | Contributors g industry insider 11 | National news 16 | International news g departments BestPractices 17 | NAVIGATOR Rewind 18 | 9-1-1 Education 21 | ACE Achievers 23 | FAQ features 24 | NAVIGATOR 26 | Hell And High Water OnTrack Calls from the stranded, sinking, or suddenly 33 | Medical CDE sunk flooded the lines as Hurricane Sandy Understanding mechanism of blew its way along the Eastern Coast. injury is vital to pre-hospital care. 36 | Police CDE 30 | Shooting Spree Caller in Danger Protocol puts safety first. Dispatchers at the Clackamas County Comm. Center jumped into action at reports of an YourSpace active shooter at the county’s largest mall. 40 | Dispatch In Action 42 | Off Hours Correction The Medical CDE quiz in the November/December 2012 Journal (She’s Having A Baby) included a question that will not be counted as either correct or incorrect. The question (#2) suggested that the MPDS® was designed to handle any possible situation or scenario related to childbirth and pregnancy. While the MPDS was developed to guide EMDs through many probable situations, no protocol is designed to handle all situations.