500 Nonstrategic Warheads

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Nuclear Technology

Nuclear Technology Joseph A. Angelo, Jr. GREENWOOD PRESS NUCLEAR TECHNOLOGY Sourcebooks in Modern Technology Space Technology Joseph A. Angelo, Jr. Sourcebooks in Modern Technology Nuclear Technology Joseph A. Angelo, Jr. GREENWOOD PRESS Westport, Connecticut • London Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data Angelo, Joseph A. Nuclear technology / Joseph A. Angelo, Jr. p. cm.—(Sourcebooks in modern technology) Includes index. ISBN 1–57356–336–6 (alk. paper) 1. Nuclear engineering. I. Title. II. Series. TK9145.A55 2004 621.48—dc22 2004011238 British Library Cataloguing in Publication Data is available. Copyright © 2004 by Joseph A. Angelo, Jr. All rights reserved. No portion of this book may be reproduced, by any process or technique, without the express written consent of the publisher. Library of Congress Catalog Card Number: 2004011238 ISBN: 1–57356–336–6 First published in 2004 Greenwood Press, 88 Post Road West, Westport, CT 06881 An imprint of Greenwood Publishing Group, Inc. www.greenwood.com Printed in the United States of America The paper used in this book complies with the Permanent Paper Standard issued by the National Information Standards Organization (Z39.48–1984). 10987654321 To my wife, Joan—a wonderful companion and soul mate Contents Preface ix Chapter 1. History of Nuclear Technology and Science 1 Chapter 2. Chronology of Nuclear Technology 65 Chapter 3. Profiles of Nuclear Technology Pioneers, Visionaries, and Advocates 95 Chapter 4. How Nuclear Technology Works 155 Chapter 5. Impact 315 Chapter 6. Issues 375 Chapter 7. The Future of Nuclear Technology 443 Chapter 8. Glossary of Terms Used in Nuclear Technology 485 Chapter 9. Associations 539 Chapter 10. -

Heater Element Specifications Bulletin Number 592

Technical Data Heater Element Specifications Bulletin Number 592 Topic Page Description 2 Heater Element Selection Procedure 2 Index to Heater Element Selection Tables 5 Heater Element Selection Tables 6 Additional Resources These documents contain additional information concerning related products from Rockwell Automation. Resource Description Industrial Automation Wiring and Grounding Guidelines, publication 1770-4.1 Provides general guidelines for installing a Rockwell Automation industrial system. Product Certifications website, http://www.ab.com Provides declarations of conformity, certificates, and other certification details. You can view or download publications at http://www.rockwellautomation.com/literature/. To order paper copies of technical documentation, contact your local Allen-Bradley distributor or Rockwell Automation sales representative. For Application on Bulletin 100/500/609/1200 Line Starters Heater Element Specifications Eutectic Alloy Overload Relay Heater Elements Type J — CLASS 10 Type P — CLASS 20 (Bul. 600 ONLY) Type W — CLASS 20 Type WL — CLASS 30 Note: Heater Element Type W/WL does not currently meet the material Type W Heater Elements restrictions related to EU ROHS Description The following is for motors rated for Continuous Duty: For motors with marked service factor of not less than 1.15, or Overload Relay Class Designation motors with a marked temperature rise not over +40 °C United States Industry Standards (NEMA ICS 2 Part 4) designate an (+104 °F), apply application rules 1 through 3. Apply application overload relay by a class number indicating the maximum time in rules 2 and 3 when the temperature difference does not exceed seconds at which it will trip when carrying a current equal to 600 +10 °C (+18 °F). -

April 4, 2003, Board Letter Establishing a 60-Day Reporting

John T. Conway, Chairman A.J. Eggenbe,ger, Vice Chairman DEFENSE NUCLFAR FACILITIES John E. Mansfield SAFE'IY BOARD 625 Indiana Avenue, NW, Suite 700, Washington, D.C. 20004-2901 (202) 694-7000 April 4, 2003 The Honorable Linton Brooks Acting Administrator of the National Nuclear Security Administration U.S. Department ofEnergy 1000 Independence A venue, SW Washington, DC 20585-0701 Dear Ambassador Brooks: During the past 16 months, the Defense Nuclear Facilities Safety Board (Board) has held a number of reviews at the Pantex Plant to evaluate conduct ofoperations and the site's training programs. The Board is pleased to see that procedural adherence and conduct ofoperations for operational personnel are improving and that a program to improve operating procedures is ongoing. However, a review by the Board's staff has revealed problems at Pantex with the processes used to develop training, to evaluate personnel knowledge, to assess training program elements, and to conduct continuing training. These training deficiencies, detailed in the enclosed report, may affect the ability to improve and maintain satisfactory conduct of operations at the Pantex Plant. Therefore, pursuant to 42 U.S.C. § 2286b(d), the Board requests a report within the next 60 days regarding the measures that are being taken to address these training deficiencies. Sincerely, c: The Honorable Everet H. Beckner Mr. Daniel E. Glenn Mr. Mark B. Whitaker, Jr. Enclosure DEFENSE NUCLEAR FACILITIES SAFETY BOARD Staff Issue Report March 24, 2003 MEMORANDUM FOR: J. K. Fortenberry, Technical Director COPIES: Board Members FROM: J. Deplitch SUBJECT: Conduct ofOperations and Training Programs at the Pantex Plant This report documents a review by the staff ofthe Defense Nuclear Facilities Safety Board (Board) ofconduct ofoperations and the training programs at the Pantex Plant. -

Bob Farquhar

1 2 Created by Bob Farquhar For and dedicated to my grandchildren, their children, and all humanity. This is Copyright material 3 Table of Contents Preface 4 Conclusions 6 Gadget 8 Making Bombs Tick 15 ‘Little Boy’ 25 ‘Fat Man’ 40 Effectiveness 49 Death By Radiation 52 Crossroads 55 Atomic Bomb Targets 66 Acheson–Lilienthal Report & Baruch Plan 68 The Tests 71 Guinea Pigs 92 Atomic Animals 96 Downwinders 100 The H-Bomb 109 Nukes in Space 119 Going Underground 124 Leaks and Vents 132 Turning Swords Into Plowshares 135 Nuclear Detonations by Other Countries 147 Cessation of Testing 159 Building Bombs 161 Delivering Bombs 178 Strategic Bombers 181 Nuclear Capable Tactical Aircraft 188 Missiles and MIRV’s 193 Naval Delivery 211 Stand-Off & Cruise Missiles 219 U.S. Nuclear Arsenal 229 Enduring Stockpile 246 Nuclear Treaties 251 Duck and Cover 255 Let’s Nuke Des Moines! 265 Conclusion 270 Lest We Forget 274 The Beginning or The End? 280 Update: 7/1/12 Copyright © 2012 rbf 4 Preface 5 Hey there, I’m Ralph. That’s my dog Spot over there. Welcome to the not-so-wonderful world of nuclear weaponry. This book is a journey from 1945 when the first atomic bomb was detonated in the New Mexico desert to where we are today. It’s an interesting and sometimes bizarre journey. It can also be horribly frightening. Today, there are enough nuclear weapons to destroy the civilized world several times over. Over 23,000. “Enough to make the rubble bounce,” Winston Churchill said. The United States alone has over 10,000 warheads in what’s called the ‘enduring stockpile.’ In my time, we took care of things Mano-a-Mano. -

Price List Eur up by Lendager Group Price List Eur up Page 1 / 6

PRICE LIST EUR UP BY LENDAGER GROUP PRICE LIST EUR UP PAGE 1 / 6 INDEX 3 UP KITCHEN All prices are incl. VAT and without delivery. Dimensions are in cm. PRICE LIST EUR UP KITCHEN PAGE 2 / 6 Kitchen pricing This is your guide to pricing on the UP kitchen by Lendager Group. The design is compatible with our own cabinets and IKEA’s METOD kitchen. For more information, visit the dedicated UP page on reformcph.com All prices are incl. VAT and without delivery. Dimensions are in cm. PRICE LIST EUR UP KITCHEN PAGE 3 / 6 Door Measurement Solid wood Veneer W20 x H80 - 244 EUR W26 x H80 (2 pcs.) - 528 EUR W30 x H40 192 EUR - W30 x H60 - 252 EUR W30 x H80 - 282 EUR W40 x H40 228 EUR - W40 x H60 - 282 EUR W40 x H80 - 322 EUR W40 x H100 - 360 EUR W40 x H120 - 400 EUR W40 x H140 - 438 EUR W40 x H160 - 478 EUR W40 x H180 - 518 EUR W40 x H200 - 556 EUR W60 x H40 300 EUR - W60 x H60 - 340 EUR W60 x H80 - 400 EUR W60 x H100 - 460 EUR W60 x H120 - 518 EUR W60 x H140 - 578 EUR W60 x H160 - 636 EUR W60 x H180 - 696 EUR W60 x H200 - 754 EUR Drawer front Measurement Solid wood Veneer W40 x H10 156 EUR - W40 x H20 156 EUR - W40 x H40 228 EUR - W40 x H60 - 282 EUR W60 x H10 192 EUR - W60 x H15 192 EUR - W60 x H20 192 EUR - W60 x H40 300 EUR - W60 x H60 - 340 EUR W80 x H10 228 EUR - W80 x H20 228 EUR - W80 x H40 370 EUR - W80 x H60 - 400 EUR All prices are incl. -

US Nuclear Weapons Capability 【Overview】 with the U.S

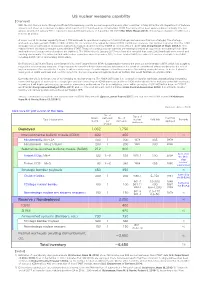

US nuclear weapons capability 【Overview】 With the U.S. there is more (though insufficient) transparency over its nuclear weapons than any other countries’. In May 2010, the U.S. Department of Defense issued a fact sheet on its nuclear stockpile, which reported 5,113 warheads as of September 2009. Ever since, it has been updated almost annually. The last update, provided in January 2017, reported a total 4,018 warheads as of September 30, 2016(The White House 2017), indicating a reduction of 1,095 over a seven‒year period. A closer look at its nuclear capability shows 1,750 warheads in operational deployment (1,600 strategic warheads and 150 non‒strategic). The strategic warheads are deployed with ICBMs, SLBMs and U.S. Air Force bases. The remainder (about 2,050) constitutes a reserve. This number is greater than the 1,393 strategic nuclear warheads in operational deployment registered under the New START as on September 1, 2017 (U.S. Department of State 2018‒1). One reason for the discrepancy may be due to the New START Treaty of counting only one warhead per strategic bomber, as opposed to accounting for all other warheads stored on base where bombers are stationed. The White House’s January 2017 fact sheet also revealed that some 2,800 warheads were retired and awaiting disassembly. It is estimated that, with further reductions since September 2017 to have totaled 3,800, the entire U.S. nuclear stockpile to be 6,450 including 2,650 retired and awaiting disassembly. On February 2, 2018, the Trump administration’s Nuclear Posture Review (NPR) fundamentally reversed the previous administration’s NPR, which had sought to reduce the role of nuclear weapons. -

The Tripartite Council of Khanbogd Soum, Umnugovi Aimag Cover Letter to Final Report of MDT and IEP

The Tripartite Council of Khanbogd soum, Umnugovi aimag Cover Letter to Final Report of MDT and IEP Khanbogd soum Umnugovi aimag Mongolia January 12, 2017 The reports of the socio-economic study of Khanbogd soum herder households and Phase 2 study of cumulative impact of Undai River diversion conducted by the independent experts employed by the Tripartite Council (TPC)1 of Khanbogd soum, Umnugovi aimag, are hereby disclosed to the public. This study was carried out to facilitate the resolution of complaints lodged by Khanbogd soum herders with the Office of the Compliance Advisor Ombudsman (CAO) of the World Bank Group. The purpose of study was to map independently and objectively the changes over the last decade in livelihood and socio-economic conditions of Khanbogd soum herder households, based on information from diverse sources, and subsequently to determine which changes were caused by or attributable to Oyu Tolgoi (OT) company operations. In addition, the study aimed to assess the adequacy of the OT’s compensation programs, cumulative impacts on regional water and pasture resources due to Undai, Khaliv and Dugat River Diversions, and impacts from OT tailings’ storage facility. Multi-Disciplinary Team (MDT) and Independent Experts’ Panel (IEP) carried out the studies in 2016 and submitted the final report to the TPC of Khanbogd Soum in January, 2017. Conclusions provided in the report by MDT and IEP are not the TPC’s position; and the report presents solely independent conclusions and assessments of the independent experts. We notify any interested entities herein that some conclusions of the report are not fully accepted by the parties of TPC. -

Nuclear Weapons Databook, Volume I 3 Stockpile

3 Stockpile Chapter Three USNuclear Stockpile This section describes the 24 types of warheads cur- enriched uranium (oralloy) as its nuclear fissile material rently in the U.S. nuclear stockpile. As of 1983, the total and is considered volatile and unsafe. As a result, its number of warheads was an estimated 26,000. They are nuclear materials and fuzes are kept separately from the made in a wide variety of configurations with over 50 artillery projectile. The W33 can be used in two differ- different modifications and yields. The smallest war- ent yield configurations and requires the assembly and head is the man-portable nuclear land mine, known as insertion of distinct "pits" (nuclear materials cores) with the "Special Atomic Demolition Munition" (SADM). the amount of materials determining a "low" or '4high'' The SADM weighs only 58.5 pounds and has an explo- yield. sive yield (W54) equivalent to as little as 10 tons of TNT, In contrast, the newest of the nuclear warheads is the The largest yield is found in the 165 ton TITAN I1 mis- W80,5 a thermonuclear warhead built for the long-range sile, which carries a four ton nuclear warhead (W53) Air-Launched Cruise Missile (ALCM) and first deployed equal in explosive capability to 9 million tons of TNT, in late 1981. The W80 warhead has a yield equivalent to The nuclear weapons stockpile officially includes 200 kilotons of TNT (more than 20 times greater than the only those nuclear missile reentry vehicles, bombs, artil- W33), weighs about the same as the W33, utilizes the lery projectiles, and atomic demolition munitions that same material (oralloy), and, through improvements in are in "active service."l Active service means those electronics such as fuzing and miniaturization, repre- which are in the custody of the Department of Defense sents close to the limits of technology in building a high and considered "war reserve weapons." Excluded are yield, safe, small warhead. -

Report Is Available on the UCS Website At

Making Smart Security Choices The Future of the U.S. Nuclear Weapons Complex Making Smart SecurityChoices The Future of the U.S. Nuclear Weapons Complex Lisbeth Gronlund Eryn MacDonald Stephen Young Philip E. Coyle III Steve Fetter OCTOBER 2013 Revised March 2014 ii UNION OF CONCERNED SCIENTISTS © 2013 Union of Concerned Scientists All rights reserved Lisbeth Gronlund is a senior scientist and co-director of the Union of Concerned Scientists (UCS) Global Security Program. Eryn MacDonald is an analyst in the UCS Global Security Program. Stephen Young is a senior analyst in the UCS Global Security Program. Philip E. Coyle III is a senior science fellow at the Center for Arms Control and Non-Proliferation. Steve Fetter is a professor in the School of Public Policy at the University of Maryland. The Union of Concerned Scientists puts rigorous, independent science to work to solve our planet’s most pressing problems. Joining with citizens across the country, we combine technical analysis and effective advocacy to create innovative, practical solutions for a healthy, safe, and sustainable future. More information about UCS and the Global Security Program is available on the UCS website at www.ucsusa.org/nuclear_weapons_and_global_security. The full text of this report is available on the UCS website at www.ucsusa.org/smartnuclearchoices. DESIGN & PROductiON DG Communications/www.NonprofitDesign.com COVER image Department of Defense/Wikimedia Commons Four B61 nuclear gravity bombs on a bomb cart at Barksdale Air Force Base in Louisiana. Printed on recycled paper. MAKING SMART SECURITY CHOICES iii CONTENTS iv Figures iv Tables v Acknowledgments 1 Executive Summary 4 Chapter 1. -

Potency Is More Than Just a Number

Potency Is More Than Just A Number It can be difficult to discriminate between the multitude of available probiotic brands and formulations. As such, it may be tempting to begin with the numbers: CFU count, number of strains, serving size, price. But the real indicators of reliable probiotic performance are driven by thoughtful science-based formulation, demonstrable mechanisms, quality manufacturing, and peer reviewed outcomes. OMNi-BiOTiC® Delivers Probiotic Performance SIGNIFICANCE SURVIVAL Every OMNi-BiOTiC strain is identified and extensively Every formulation is tested for gastric survival, intestinal analyzed to determine its strengths and suitability for viability, metabolic activity, and extended real time shelf indication-focused formulations. In vitro studies include: stability. These quality processes ensure OMNi-BiOTiC consistently delivers real world performance. • Transepithelial electrical resistance (TEER) • Mast cell degranulation testing • Proprietary ProbioAct® Technology assures • Short chain fatty acid production (SCFA) microbial viability • Anti-inflammatory cytokine production • Intestinal metabolic activity is assessed in • Alkaline phosphatase activity vitro/in vivo • Toxin reduction capabilities • Extended real time stability testing for up to 36 months at room temperature SYNERGY Every multi-strain formulation is powered for syner- I Strain discovery: isolation and identification N gistic activity, validated through animal models and functional T Strain safety assessment E E F controlled human trials. OMNi-BiOTiC -

Online NC K-12 Championship Charlotte Chess Center

3/18/2021 Online NC K-12 Championship ~ Charlotte Chess Center 2021 North Carolina Online K-12 Championship K-12 Championship, K-8 Championship, K-5 Championship, K-3 Championship, K-1 Championship, K-12 U1500, K-8 U1200 and Blitz Championship sections Saturday-Sunday, March 6-7, 2021 INFO REGISTER ENTRIES PAIRINGS STANDINGS TEAMS GAMES HOW TO PLAY LIVE HELP FAQ PRIZES Individual Standings K-12 CHAMPIONSHIP K-12 U1500 K-8 CHAMPIONSHIP K-8 U1200 K-5 CHAMPIONSHIP K-3 CHAMPIONSHIP K-1 CHAMPIONSHIP K-12 BLITZ K-6 BLITZ PLAYOFF Standings Round 6/6 ~ Current live games: 0 No. Team Player's Name Rating Rnd1 Rnd2 Rnd3 Rnd4 Rnd5 Rnd6 Score Tb1 Tb2 Tb3 Tb4 Award 1 NCKOONTZT VIR DATT 1121 W65 D23 W46 W24 W8 W3 5.5 19 21 18.5 81 1st 2 NCGREYF ENZO RESTELLI 1559 W33 W5 W35 W4 L3 W12 5 22 25 19 91 2nd 3 NCMETRO SMAYAN AMMASANI 1614 W58 W34 W16 W11 W2 L1 5 21.5 23.5 20 87.5 3rd 4 NCELON ETHAN LIU 1790 W32 W50 W26 L2 W22 W7 5 19.5 22 18 85 4th 5 NCMORRIS AARNA GUPTA 882 W36 L2 W59 W48 W11 W15 5 18 20 16 75 5th 6 NCHUNTR AARAV TRIVEDI 1089 L22 W62 W61 W56 W37 W14 5 15 17 15 66 6th 7 NCWESLEY SAHASRA RALLABANDI 1336 W19 W12 D25 W10 W9 L4 4.5 22 25.5 18 89 7th 8 NCGHOES LILLIAN YANG 1268 W15 W14 D22 W45 L1 W13 4.5 21 23.5 17 92 8th 9 NCDA JUDSON ROEDERER 1212 H W47 W23 W25 L7 W24 4.5 17.5 17.5 15.5 70.5 9th 10 NCELON NAMISH KONDABATHINI 1076 W39 D45 W27 L7 W46 W23 4.5 17 19.5 15.5 76 10th 11 NCDA LINGAA VENKATARAJA 1352 W72 W28 W13 L3 L5 W37 4 21 22 16 81 11th 12 NCBARR ISHAN SUNDARAM 841 W71 L7 W51 W26 W21 L2 4 19.5 20.5 15 76 12th 13 NCHUNTR EMMETT WALLS -

Chapter Nine Army Nuclear Weapons

9 Army Nuclear Weapons Chapter Nine Army Nuclear Weapons The Army1 uses a wide variety of nuclear weapon sys- ish, Dutch, Italian, and West German armies. LANCE tems-medium range PERSHING la and short-range replaced HONEST JOHN in all of these countries, more LANCE surface-to-surface missiles, NIKE-HERCULES than doubling the range and accuracy over the older surface-to-air missiles, 155mm and 8-inch (203mm) artil- missile, and providing greater mobility and reliability. lery, and atomic demolition munitions (nuclear land A new warhead for the LANCE, an enhanced radiation mines). The HONEST JOHN surface-to-surface rocket, version of the W70 (Mod 3) produced in 1981-1983, is although withdrawn from active U.S. use, is nuclear being stored in the U.S. and awaits shipment to armed with some NATO allies. Army nuclear weapons Europe. The HONEST JOHN short-range free-flight are deployed with U.S. combat units throughout the rocket, first deployed in 1954, remains deployed with United States, Europe, in South Korea, and among allied W31 nuclear warheads in the Greek and Turkish military forces. They vary in range from manually armies. No plans are currently known for the replace- emplaced land mines to 460 miles, and in yield from sub ment of HONEST JOHN in the above forces with the (0.01) to 400 kilotons. LANCE, but they will be obsolete in the late 1980s and The PERSHING la is the longest range and highest impossible to support. A nuclear armed LANCE yield Army nuclear weapon currently deployed. One replacement is under development, called the Corps hundred and eighty launchers, with more than 300 mis- Support Weapon System, as part of the Army-Air Force siles, all armed with W50 nuclear warheads, are Joint Tactical Missile System program to investigate deployed in West Germany with the U.S.