Journal Humanities

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

When Diplomats Fail: Aostrian and Rossian Reporting from Belgrade, 1914

WHEN DIPLOMATS FAIL: AOSTRIAN AND ROSSIAN REPORTING FROM BELGRADE, 1914 Barbara Jelavich The mountain of books written on the origins of the First World War have produced no agreement on the basic causes of this European tragedy. Their division of opinion reflects the situation that existed in June and July 1914, when the principal statesmen involved judged the assassination of Franz Ferdinand, heir to the Habsburg throne, and its consequences from radically different perspectives. Their basic misunderstanding of the interests and viewpoints 'of the opposing sides contributed strongly to the initiation of hostilities. The purpose of this paper is to emphasize the importance of diplomatic reporting, particularly in the century before 1914 when ambassadors were men of influence and when their dispatches were read by those who made the final decisions in foreign policy. European diplomats often held strong opinions and were sometimes influenced by passions and. prejudices, but nevertheless throughout the century their activities contributed to assuring that this period would, with obvious exceptions, be an era of peace in continental affairs. In major crises the crucial decisions are always made by a very limited number of people no matter what the political system. Usually a head of state -- whether king, emperor, dictator, or president, together with those whom he chooses to consult, or a strong political leader with his advisers- -decides on the course of action. Obviously, in times of international tension these men need accurate information not only from their military staffs on the state of their and their opponent's armed forces and the strategic position of the country, but also expert reporting from their representatives abroad on the exact issues at stake and the attitudes of the other governments, including their immediate concerns and their historical background. -

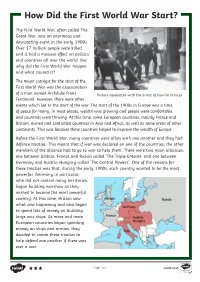

How Did the First World War Start?

How Did the First World War Start? The First World War, often called The Great War, was an enormous and devastating event in the early 1900s. Over 17 million people were killed and it had a massive effect on politics and countries all over the world. But why did the First World War happen and what caused it? The major catalyst for the start of the First World War was the assassination of a man named Archduke Franz Picture associated with the arrest of Gavrilo Princip Ferdinand. However, there were other events which led to the start of the war. The start of the 1900s in Europe was a time of peace for many. In most places, wealth was growing and people were comfortable and countries were thriving. At this time, some European countries, mainly France and Britain, owned and controlled countries in Asia and Africa, as well as some areas of other continents. This was because these countries helped to improve the wealth of Europe. Before the First World War, many countries were allies with one another and they had defence treaties. This meant that if war was declared on one of the countries, the other members of the alliance had to go to war to help them. There were two main alliances, one between Britain, France and Russia called ‘The Triple Entente’ and one between Germany and Austria-Hungary called ‘The Central Powers’. One of the reasons for these treaties was that, during the early 1900s, each country wanted to be the most powerful. Germany in particular, who did not control many territories, began building warships as they wished to become the most powerful country. -

Blood Ties: Religion, Violence, and the Politics of Nationhood in Ottoman Macedonia, 1878

BLOOD TIES BLOOD TIES Religion, Violence, and the Politics of Nationhood in Ottoman Macedonia, 1878–1908 I˙pek Yosmaog˘lu Cornell University Press Ithaca & London Copyright © 2014 by Cornell University All rights reserved. Except for brief quotations in a review, this book, or parts thereof, must not be reproduced in any form without permission in writing from the publisher. For information, address Cornell University Press, Sage House, 512 East State Street, Ithaca, New York 14850. First published 2014 by Cornell University Press First printing, Cornell Paperbacks, 2014 Printed in the United States of America Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data Yosmaog˘lu, I˙pek, author. Blood ties : religion, violence,. and the politics of nationhood in Ottoman Macedonia, 1878–1908 / Ipek K. Yosmaog˘lu. pages cm Includes bibliographical references and index. ISBN 978-0-8014-5226-0 (cloth : alk. paper) ISBN 978-0-8014-7924-3 (pbk. : alk. paper) 1. Macedonia—History—1878–1912. 2. Nationalism—Macedonia—History. 3. Macedonian question. 4. Macedonia—Ethnic relations. 5. Ethnic conflict— Macedonia—History. 6. Political violence—Macedonia—History. I. Title. DR2215.Y67 2013 949.76′01—dc23 2013021661 Cornell University Press strives to use environmentally responsible suppliers and materials to the fullest extent possible in the publishing of its books. Such materials include vegetable-based, low-VOC inks and acid-free papers that are recycled, totally chlorine-free, or partly composed of nonwood fibers. For further information, visit our website at www.cornellpress.cornell.edu. Cloth printing 10 9 8 7 6 5 4 3 2 1 Paperback printing 10 9 8 7 6 5 4 3 2 1 To Josh Contents Acknowledgments ix Note on Transliteration xiii Introduction 1 1. -

The Internal Macedonian-Adrianople Revolutionary Organization and the Idea for Autonomy for Macedonia and Adrianople Thrace

The Internal Macedonian-Adrianople Revolutionary Organization and the Idea for Autonomy for Macedonia and Adrianople Thrace, 1893-1912 By Martin Valkov Submitted to Central European University Department of History In partial fulfilment of the requirements for the degree of Master of Arts Supervisor: Prof. Tolga Esmer Second Reader: Prof. Roumen Daskalov CEU eTD Collection Budapest, Hungary 2010 “Copyright in the text of this thesis rests with the Author. Copies by any process, either in full or part, may be made only in accordance with the instructions given by the Author and lodged in the Central European Library. Details may be obtained from the librarian. This page must form a part of any such copies made. Further copies made in accordance with such instructions may not be made without the written permission of the Author.” CEU eTD Collection ii Abstract The current thesis narrates an important episode of the history of South Eastern Europe, namely the history of the Internal Macedonian-Adrianople Revolutionary Organization and its demand for political autonomy within the Ottoman Empire. Far from being “ancient hatreds” the communal conflicts that emerged in Macedonia in this period were a result of the ongoing processes of nationalization among the different communities and the competing visions of their national projects. These conflicts were greatly influenced by inter-imperial rivalries on the Balkans and the combination of increasing interference of the Great European Powers and small Balkan states of the Ottoman domestic affairs. I argue that autonomy was a multidimensional concept covering various meanings white-washed later on into the clean narratives of nationalism and rebirth. -

THE WARP of the SERBIAN IDENTITY Anti-Westernism, Russophilia, Traditionalism

HELSINKI COMMITTEE FOR HUMAN RIGHTS IN SERBIA studies17 THE WARP OF THE SERBIAN IDENTITY anti-westernism, russophilia, traditionalism... BELGRADE, 2016 THE WARP OF THE SERBIAN IDENTITY Anti-westernism, russophilia, traditionalism… Edition: Studies No. 17 Publisher: Helsinki Committee for Human Rights in Serbia www.helsinki.org.rs For the publisher: Sonja Biserko Reviewed by: Prof. Dr. Dubravka Stojanović Prof. Dr. Momir Samardžić Dr Hrvoje Klasić Layout and design: Ivan Hrašovec Printed by: Grafiprof, Belgrade Circulation: 200 ISBN 978-86-7208-203-6 This publication is a part of the project “Serbian Identity in the 21st Century” implemented with the assistance from the Open Society Foundation – Serbia. The contents of this publication are the sole responsibility of the Helsinki Committee for Human Rights in Serbia, and do not necessarily reflect the views of the Open Society Foundation – Serbia. CONTENTS Publisher’s Note . 5 TRANSITION AND IDENTITIES JOVAN KOMŠIĆ Democratic Transition And Identities . 11 LATINKA PEROVIĆ Serbian-Russian Historical Analogies . 57 MILAN SUBOTIĆ, A Different Russia: From Serbia’s Perspective . 83 SRĐAN BARIŠIĆ The Role of the Serbian and Russian Orthodox Churches in Shaping Governmental Policies . 105 RUSSIA’S SOFT POWER DR. JELICA KURJAK “Soft Power” in the Service of Foreign Policy Strategy of the Russian Federation . 129 DR MILIVOJ BEŠLIN A “New” History For A New Identity . 139 SONJA BISERKO, SEŠKA STANOJLOVIĆ Russia’s Soft Power Expands . 157 SERBIA, EU, EAST DR BORIS VARGA Belgrade And Kiev Between Brussels And Moscow . 169 DIMITRIJE BOAROV More Politics Than Business . 215 PETAR POPOVIĆ Serbian-Russian Joint Military Exercise . 235 SONJA BISERKO Russia and NATO: A Test of Strength over Montenegro . -

Moderno BELGRADO

moderno BELGRADO Legado y alteridad de la urbanidad Europea Mila Nikolic Episodios Urbanos Significativos: Liberation of Belgrade 1789 Marshal Gideon Ernst Laudon captures Belgrade 1791 Peace treaty of Svishtov gives Belgrade back to the Turks 1806 Karađorđe liberates Belgrade town and Belgrade becomes the capital of Serbia again 1808 The Great School was established in Belgrade 1813 The Turks reconquer Belgrade 1815 Miloš Obrenović started the Second Serbian Insurrection 1830 Sultan's hatišerif (charter) on Serbian autonomy 1831 First printing-house in Belgrade was put into operation 1835 First newspaper - "Novine srbske" is published in Belgrade 1840 Opening of the first post office in Belgrade 1841 Belgrade becomes the capital of the Princedom of Serbia in the first period of rule of Mihailo Obrenović 1844 The National Museum was established in Belgrade 1855 First telegraphic line Belgrade - Aleksinac was established 1862 Conflict at Čukur-česma and bombardment of Belgrade town from the fortress under Turkish control led to international decision that the Turks must leave Belgrade 1854 ~1815 Episodios Urbanos Significativos The Capital of Serbia and Yugoslavia 1867 In Kalemegdan, the Turkish commander of Belgrade Ali-Riza pasha gives the keys of Belgrade to Knez Mihailo. The Turks finally leave Belgrade 1878 The Berlin Congress recognized the independence of Serbia 1882 Serbia becomes a kingdom, and Belgrade its capital 1883 First telephone lines are installed in Belgrade 1884 Railway station and railway bridge over Sava were constructed -

Los Levantamientos De 1903 En Macedonia Y Tracia

"Abajo el Sultán, ¡Viva la Federación balcánica!" Los levantamientos de 1903 en Macedonia y Tracia Traducido del Búlgaro al Inglés por Will Firth (con fondos del Institute for Anarchist Studies). Gracias a Koicho Koichev por su ayuda con las expresiones difíciles. Traducido del Inglés al Castellano por M. Gómez. Imágenes de la Wikipedia y Wikicommons. Macedonia y Tracia, 1903. El Imperio Turco-Otomano estaba en un estado de decadencia. Durante siglos las autoridades habían gobernado un puño de hierro, imponiendo impuestos y otras obligaciones, pero en la mayoría de los casos permitiendo a las personas a hablar sus propias lenguas y a practicar sus propias religiones. Ahora, sin embargo, se vivían tiempos de crisis. Las fronteras del Imperio estaban retrocediendo y el control Otomano se volvió cada vez más duro y arbitrario. El espectro de las luchas de liberación amenazaban las posesiones cada vez menores en el sur de los Balcanes. Una insurrección brutalmente aplastada seguía a otra insrrección aplastada, así durante generaciones. Sin embargo ahora parecía que la hora había llegado: imbuidos con el espíritu de justicia e igualdad vivos en las comunidades de los pueblos y las aldeas, los campesinos y los artesanos se aliaron para liberarse de los males duales de la servitud feudal y la ocupación turca - para los rebeldes ambas fuerzas de represión eran lo mismo. Parece que la población, principalmente eslava, en Macedonia y Tracia veía el principado de Bulgaria, que había recibido una gran autonomía del Imperio Otomano en 1878, como una clase de modelo para su lucha anto- otomana. Bulgaria también tenía una importancia logística para los revolucionarios de Macedonia y Tracia - les daba armas y se producían explosivos que serían empleados en actos de sabotaje en las áreas bajo dominio directo turco. -

Prilozi 43 2014 Eng.Indd

%RMDQ$OHNVRYForgotten Yugoslavism and anti-clericalism of Young Bosnians Prilozi • Contributions, 43, Sarajevo, 2014, 79-87 UDK 329.78(497.15)"1906/1914" )25*277(1<8*26/$9,60$1'$17,&/(5,&$/,60 2)<281*%261,$16 %RMDQ$OHNVRY 8&/6FKRRORI6ODYRQLFDQG(DVW(XURSHDQ6WXGLHV/RQGRQ Abstract: Worldviews and political ambitions of Young Bosnians were a far cry from later and contemporary emanations of Serbian nationalism, as evident in the- ir Yugoslavism and staunch anti-clericalism. They should neither be praised for what they did nor blamed for what happened later. Their act can be understood and interpreted only in its own historical context, which opens new avenues for resear- ch away from false analogies and political abuses. 7KHUHLVDQROGQREOHFXVWRPSUDFWLVHGLQWKH8QLWHG.LQJGRPZKHUHE\DFDGHP- LFV DQGRWKHUV GHFODUHDQLQWHUHVWZKHQGLVFXVVLQJPDWWHUVSHUVRQVWRZKLFKWKH\ might have a relation. Unfortunately this has not been the case in the historiography RIWKRVHKLJKO\GLVSXWHGLVVXHVVXFKDVWKHRULJLQVRI)LUVW:RUOG:DU1 Despite the IDFWWKDWGRFXPHQWDU\HYLGHQFHIURPDOOVLGHVZDVSXEOLVKHGDOUHDG\LQWKHLQWHUZDU SHULRGWKHGLIIHUHQFHVRILQWHUSUHWDWLRQDQGRSLQLRQDELGHRUHYHQLQFUHDVHZLWKWLPH VRWKDWZKDWLVEHLQJZULWWHQRIWHQUHIOHFWVWKHFRQWH[WDQGEDFNJURXQGRILWVDXWKRU UDWKHUWKDQWKHHYHQWDQDO\VHG,ZDQWWREUHDNWKLVFLUFOHRIXQDFNQRZOHGJHGELDV E\GHFODULQJWKDW,ZDVERUQDQGUDLVHGLQWKHVWUHHWEHDULQJWKHQDPHRI1HGHOMNR ýDEULQRYLüWKHIDLOHG6DUDMHYRERPEHUDQGWKXVIURPHDUO\DJHVXEMHFWWRWKHJUDQG 6RFLDOLVW<XJRVODYLD¶VQDUUDWLYHRI<RXQJ%RVQLDQVDVIUHHGRPILJKWHUVDQG<XJR- 1)RUWKHPDQLSXODWLRQRIDUFKLYDOUHFRUGVDQGHYLGHQFHUHODWLQJWKHWKHUHVSRQVLELOLW\IRUWKH -

The Macedonian Question: a Historical Overview

Ivanka Vasilevska THE MACEDONIAN QUESTION: A HISTORICAL OVERVIEW There it is that simple land of seizures and expectations / That taught the stars to whisper in Macedonian / But nobody knows it! Ante Popovski Abstract In the second half of the XIX century on the Balkan political stage the Macedonian question was separated as a special phase from the great Eastern question. Without the serious support by the Western powers and without Macedonian millet in the borders of the Empire, this question became a real Gordian knot in which, until the present times, will entangle and leave their impact the irredentist aspirations for domination over Macedonia and its population by the Balkan countries – Greece, Bulgaria and Serbia. The consequence of the Balkan wars and the World War I was the territorial dividing of ethnic Macedonia. After the collapse of the Ottoman Empire, the territory of Macedonia was divided among Serbia, Greece and Bulgaria, an act of the Balkan countries which, instead of being sanctioned has received an approval, with the confirmation of their legitimacy made with the treaties introduced by the Versailles world order. Divided with the state borders, after 1919 the Macedonian nation was submitted to a severe economic exploitation, political deprivation, national non-recognition and oppression, with a final goal - to be ethnically liquidated. In essence, the Macedonian question was not recognized as an ethnic problem because the conditions from the past and the powerful propaganda machines of the three neighboring countries - Serbia, Greece and Bulgaria, made the efforts to make the impression before the world public that the Macedonian ethnicity did not exist, while Macedonia was mainly treated as a geographical term, and the ethnic origin of the population on the Macedonian territory was considered exclusively as a “lost herd”, i.e. -

"Shoot the Teacher!": Education and the Roots of the Macedonian Struggle

"SHOOT THE TEACHER!" EDUCATION AND THE ROOTS OF THE MACEDONIAN STRUGGLE Julian Allan Brooks Bachelor of Arts, University of Victoria, 1992 Bachelor of Education, University of British Columbia, 200 1 THESIS SUBMITTED IN PARTIAL FULFILLMENT OF THE REQUIREMENTS FOR THE DEGREE OF MASTER OF ARTS In the Department of History O Julian Allan Brooks 2005 SIMON FRASER UNIVERSITY Fall 2005 All rights reserved. This work may not be reproduced in whole or in part, by photocopy or other means, without permission of the author. APPROVAL Name: Julian Allan Brooks Degree: Master of Arts Title of Thesis: "Shoot the Teacher!" Education and the Roots of the Macedonian Struggle Examining Committee: Chair: Professor Mark Leier Professor of History Professor AndrC Gerolymatos Senior Supervisor Professor of History Professor Nadine Roth Supervisor Assistant Professor of History Professor John Iatrides External Examiner Professor of International Relations Southern Connecticut State University Date Approved: DECLARATION OF PARTIAL COPYRIGHT LICENCE The author, whose copyright is declared on the title page of this work, has granted to Simon Fraser University the right to lend this thesis, project or extended essay to users of the Simon Fraser University Library, and to make partial or single copies only for such users or in response to a request from the library of any other university, or other educational institution, on its own behalf or for one of its users. The author has further granted permission to Simon Fraser University to keep or make a digital copy for use in its circulating collection, and, without changing the content, to translate the thesislproject or extended essays, if technically possible, to any medium or format for the purpose of preservation of the digital work. -

The Assassination of Franz Ferdinand, As It Happened - Telegraph

4/21/2015 First World War centenary: the assassination of Franz Ferdinand, as it happened - Telegraph First World War centenary: the assassination of Franz Ferdinand, as it happened On Sunday June 28 1914 in Sarajevo, Gavrilo Princip fired the shot that killed the Archduke and started the train of events that led to global war. Here is a step by step account of how the dramatic day unfolded The Daily Telegraph, June 29 1914 By Richard Preston 8:19PM BST 27 Jun 2014 Our journey starts with an extremely promising omen. Here our car burns, and down there they will throw bombs at us. Archduke Franz Ferdinand comments wryly on the fact that his journey to Bosnia in June 1914 begins with his car overheating The Archduke: Franz Ferdinand, the bumptious, littleloved 51yearold nephew of the ailing Emperor Franz Joseph, was heir presumptive to the AustroHungarian throne. In 1913 he was made inspector general of the armed forces of AustriaHungary; it was this role that took him to Bosnia in June 1914, to inspect the army’s summer manoeuvres. The Duchess: Franz Ferdinand married Countess Sophie Chotek for love, for which both paid a price. She was from a Czech noble family but was deemed unfit to be a Habsburg bride; she had been a ladyinwaiting to Archduchess Isabella, whose sister Franz Ferdinand was expected to marry. Their marriage was morganatic, meaning their children were excluded from the line of http://www.telegraph.co.uk/history/world-war-one/10930863/First-World-War-centenary-the-assassination-of-Franz-Ferdinand-as-it-happened.html 1/12 4/21/2015 First World War centenary: the assassination of Franz Ferdinand, as it happened - Telegraph succession. -

LARSON-DISSERTATION-2020.Pdf

THE NEW “OLD COUNTRY” THE KINGDOM OF YUGOSLAVIA AND THE CREATION OF A YUGOSLAV DIASPORA 1914-1951 BY ETHAN LARSON DISSERTATION Submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in History in the Graduate College of the University of Illinois at Urbana-Champaign, 2020 Urbana, Illinois Doctoral Committee: Professor Maria Todorova, Chair Professor Peter Fritzsche Professor Diane Koenker Professor Ulf Brunnbauer, University of Regensburg ABSTRACT This dissertation reviews the Kingdom of Yugoslavia’s attempt to instill “Yugoslav” national consciousness in its overseas population of Serbs, Croats, and Slovenes, as well as resistance to that same project, collectively referred to as a “Yugoslav diaspora.” Diaspora is treated as constructed phenomenon based on a transnational network between individuals and organizations, both emigrant and otherwise. In examining Yugoslav overseas nation-building, this dissertation is interested in the mechanics of diasporic networks—what catalyzes their formation, what are the roles of international organizations, and how are they influenced by the political context in the host country. The life of Louis Adamic, who was a central figure within this emerging network, provides a framework for this monograph, which begins with his arrival in the United States in 1914 and ends with his death in 1951. Each chapter spans roughly five to ten years. Chapter One (1914-1924) deals with the initial encounter between Yugoslav diplomats and emigrants. Chapter Two (1924-1929) covers the beginnings of Yugoslav overseas nation-building. Chapter Three (1929-1934) covers Yugoslavia’s shift into a royal dictatorship and the corresponding effect on its emigration policy.