US&FCS Germany

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

16 November 2018 in Bonn, Germany

United Nations/Germany High Level Forum: The way forward after UNISPACE+50 and on Space2030 13 – 16 November 2018 in Bonn, Germany USEFUL INFORMATION FOR PARTICIPANTS Content: 1. Welcome to Bonn! ..................................................................................................................... 2 2. Venue of the Forum and Social Event Sites ................................................................................. 3 3. How to get to the Venue of the Forum ....................................................................................... 4 4. How to get to Bonn from International Airports ......................................................................... 5 5. Visa Requirements and Insurance .............................................................................................. 6 6. Recommended Accommodation ............................................................................................... 6 7. General Information .................................................................................................................. 8 8. Organizing Committe ............................................................................................................... 10 Bonn, Rhineland Germany Bonn Panorama © WDR Lokalzeit Bonn 1. Welcome to Bonn! Bonn - a dynamic city filled with tradition. The Rhine and the Rhineland - the sounds, the music of Europe. And there, where the Rhine and the Rhineland reach their pinnacle of beauty lies Bonn. The city is the gateway to the romantic part of -

Berlin Is the Capital of Germany and Was the Capital of the Former Kingdom of Prussia

Berlin is the capital of Germany and was the capital of the former kingdom of Prussia. After World War II, Berlin was divided, and in 1961, the Berlin Wall was built. But the wall fell in 1989, and the country became one again in 1990. ©2015 Bonnie Rose Hudson WriteBonnieRose.com ////////////////////////////////////////////////////// ////////////////////////////////////////////////////// ////////////////////////////////////////////////////// ////////////////////////////////////////////////////// ////////////////////////////////////////////////////// ////////////////////////////////////////////////////// ////////////////////////////////////////////////////// ////////////////////////////////////////////////////// ////////////////////////////////////////////////////// ////////////////////////////////////////////////////// ////////////////////////////////////////////////////// ////////////////////////////////////////////////////// ////////////////////////////////////////////////////// ©2015 Bonnie Rose Hudson WriteBonnieRose.com Cologne/is/in/a/region/of/Germany/called/the/ Rhineland./Its/biggest/and/most/famous//////// building/is/the/Cologne/Cathedral,/a/giant///// church/that/stretches/515/feet/high!/Inside///// the/church/you/can/find/many/beautiful//////// pieces/of/art,/some/more/than/500/years/old./ Cologne/is/in/a/region/of/Germany/called/the/ Rhineland./Its/biggest/and/most/famous//////// building/is/the/Cologne/Cathedral,/a/giant///// church/that/stretches/515/feet/high!/Inside///// the/church/you/can/find/many/beautiful//////// -

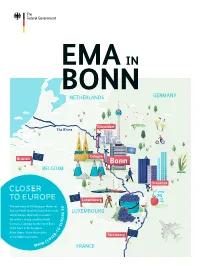

Closer to Europe — Tremendous Opportunities Close By: Germany Is Applying Interview – a Conversation with Bfarm Executive Director Prof

CLOSER TO EUROPE The new home of the European Medicines U E Agency (EMA) should be located centrally . E within Europe. Optimally accessible. P Set within a strong neigh bourhood. O R Germany is applying for the city of Bonn, U E at the heart of the European - O T Rhine Region, to be the location - R E of the EMA’s new home. S LO .C › WWW FOREWORD e — Federal Min öh iste Gr r o nn f H a e rm al e th CLOSER H TO EUROPE The German application is for a very European location: he EU 27 will encounter policy challenges Healthcare Products Regulatory Agency. The Institute Bonn. A city in the heart of Europe. Extremely close due to Brexit, in healthcare as in other ar- for Quality and Efficiency in Health Care located in T eas. A new site for the European Medicines nearby Cologne is Europe’s leading institution for ev- to Belgium, the Netherlands, France and Luxembourg. Agency (EMA) must be found. Within the idence-based drug evaluation. The Paul Ehrlich Insti- Situated within the tri-state nexus of North Rhine- EU, the organisation has become the primary centre for tute, which has 800 staff members and is located a mere drug safety – and therefore patient safety. hour and a half away from Bonn, contributes specific, Westphalia, Hesse and Rhineland-Palatinate. This is internationally acclaimed expertise on approvals and where the idea of a European Rhine Region has come to The EMA depends on close cooperation with nation- batch testing of biomedical pharmaceuticals and in re- life. -

The Impact of Public Employment: Evidence from Bonn

DISCUSSION PAPER SERIES IZA DP No. 11255 The Impact of Public Employment: Evidence from Bonn Sascha O. Becker Stephan Heblich Daniel M. Sturm JANUARY 2018 DISCUSSION PAPER SERIES IZA DP No. 11255 The Impact of Public Employment: Evidence from Bonn Sascha O. Becker University of Warwick, CAGE, CEPR and IZA Stephan Heblich University of Bristol, IZA and SERC Daniel M. Sturm London School of Economics and CEPR JANUARY 2018 Any opinions expressed in this paper are those of the author(s) and not those of IZA. Research published in this series may include views on policy, but IZA takes no institutional policy positions. The IZA research network is committed to the IZA Guiding Principles of Research Integrity. The IZA Institute of Labor Economics is an independent economic research institute that conducts research in labor economics and offers evidence-based policy advice on labor market issues. Supported by the Deutsche Post Foundation, IZA runs the world’s largest network of economists, whose research aims to provide answers to the global labor market challenges of our time. Our key objective is to build bridges between academic research, policymakers and society. IZA Discussion Papers often represent preliminary work and are circulated to encourage discussion. Citation of such a paper should account for its provisional character. A revised version may be available directly from the author. IZA – Institute of Labor Economics Schaumburg-Lippe-Straße 5–9 Phone: +49-228-3894-0 53113 Bonn, Germany Email: [email protected] www.iza.org IZA DP No. 11255 JANUARY 2018 ABSTRACT The Impact of Public Employment: Evidence from Bonn* This paper evaluates the impact of public employment on private sector activity using the relocation of the German federal government from Berlin to Bonn in the wake of the Second World War as a source of exogenous variation. -

Doing Business in Germany

DOING BUSINESS IN GERMANY CONTENTS 1 – Introduction 3 2 – Business Environment 4 3 – Foreign Investment 9 4 – Setting up a Business 11 5 – Employment 16 6 – Taxation 21 7 – Accounting & Reporting 32 8 – UHY Representation in Germany 35 DOING BUSINESS IN GERMANY 3 1 – INTRODUCTION UHY is an international organisation providing accountancy, tax business management and consultancy services through financial business centres in around 90 countries throughout the world. Through this network business partners work together. So not only specialist knowledge and experience within the own border can be offered. But, they are also able to conduct transnational operations for clients. This detailed report provides key issues and information for investors considering business operations in Germany. It has been provided by the offices of UHY representatives. A detailed firm profile of UHY’s representation in Germany can be found in section 8. You are more than welcome to contact single firms for any inquiries you may have. Information in the following pages is periodically updated. Anyway, inevitably the information given is general and subjected to change and should be used for guidance only. For specific matters, you are strongly advised to obtain further information. Additionally, you should seek for professional advice before making any decisions. This publication is current as of March 2019. We look forward helping you doing business in Germany. DOING BUSINESS IN GERMANY 4 2 – BUSINESS ENVIRONMENT GEOGRAPHY AND CLIMATE Germany is located in the centre of Europe and is one of the largest European countries. Neighbouring countries are Poland, the Czech Republic, Austria, Switzerland, France, Luxembourg, Belgium, the Netherlands and Denmark. -

German Immersion

Study Abroad German Immersion Willy Piñón heads to Europe to see what Germany has to offer to the German learner In the heart of Europe, Germany has the world’s third Marx-Haus, built in 1924. The city is home to several museums, and largest economy. Since the fall of the Berlin wall in 1989, and the the library holds a collection of works by the poet Heinrich Heine. reunification process which formally concluded in 1990, Germany has Berlin, located in the northeast, is the nation’s capital, as well as its undergone massive efforts, both governmental and individual, to largest city. It is home to world-renowned universities, and boasts restore the sense of unity that the manly created barrier had broken architectural sights of great cultural and historical significance. If you since the wall was built in 1961. Germany is politically divided into 16 are a sports fan, a tour of Berlin’s Olympiastadion, home to the final federal states, each of which is a world of adventure in itself. match of the 2006 soccer World Cup, and the 1936 Olympic Games, The state of Bavaria, located in the south east corner of the coun- is a must. try, is famous for its beautiful forests, lakes, and the best beer in the In the northwest of Germany, lies Hamburg, home of the ninth world. The state capital is the lively and fashionable city of Munich, largest harbor in the world. Emperor Charlemagne, in the year 808 AD, which is a young, liberal city ideal for students. Bavaria is also the ordered the construction of the Hamburg Castle, from which the city birthplace of Pope Benedict XVI, and home of the famous Oktoberfest, later took its name. -

Germany Ebcid:Com.Britannica.Oec2.Identifier.Articleidentifier?Tocid=0&Articleid

Germany ebcid:com.britannica.oec2.identifier.ArticleIdentifier?tocId=0&articleId... Germany Britannica Elementary Article Introduction Germany is a country of north-central Europe. It ranks among the world's leading economic powers. Germany was created in the 1800s through the unification of various European states. In the 1900s, the country was devastated by the two world wars. Flag of Germany For 45 years after World War II, Germany was divided into two countries. The German Democratic Republic, or East Germany, became a Communist country. The Federal Republic of Germany, or West Germany, prospered as a democracy. The collapse of Communism in eastern Europe in 1989 led to the reunification of Germany on 3 October 1990. The capital of Germany is Berlin. The instrumental version of the national anthem of Germany. Geography Germany is bordered by nine countries: Denmark to the north; the Czech Republic and Poland to the east; Switzerland and Austria to the south; and France, Luxembourg, Belgium and The Netherlands to the west. It also has two coasts: one eastwards from Denmark on the Baltic Sea and a second westwards from Denmark along the North Sea. One of Europe's largest countries, Germany covers an area of 356,973 square kilometres (137,828 square miles) and has a wide variety of landscapes. The southern part of the country, lying mostly within the state of Bavaria, is mountainous. The scenic Bavarian Alps reach an elevation of 2,962 metres (9,718 feet) at Zugspitze, Germany's highest peak. These alpine ranges are cut by rivers and deep, cold lakes. -

The Berlin Republic: Reunification and Reorientation Manfred Görtemaker

The Berlin Republic: Reunification and Reorientation Manfred Görtemaker The “peaceful revolution” that took place in the German Democratic Republic (GDR) in the autumn of 1989 and led to the reunification of Germany on 3 October 1990, came as a surprise to most people at the time.1 After the construction of the Berlin Wall on 13 August 1961, reunification was considered highly unlikely, if not impossible. The political, military and ideological contrast between East and West stood in the way of any fundamental change in the status quo. Even the Germans themselves had gradually become accustomed to the conditions of division. The younger generation no longer shared any personal memories of a single Germany. In addiction to the fact that since the early 1970s, the two German states had been developing “normal, good-neighbourly relations with each other on the basis of equal rights”, as stated in The Basic Treaty of 21 December 1972 between the Federal Republic of Germany and the German Democratic Republic, was generally regarded as normality.2 THE DISINTEGRATION OF THE GDR However, the appearance of stability in the GDR was only superficial. It was based on the presence of 380,000 Soviet soldiers 1 For a detailed account see Ilko-Sascha Kowalczuk, Endspiel. Die Revolution von 1989 in der DDR, München 2009. 2 Vertrag über die Grundlagen der Beziehungen zwischen der Bundesrepublik Deutschland und der Deutschen Demokratischen Republik vom 21. Dezember 1972, in: Dokumente des geteilten Deutschland. Mit einer Einführung hrsg. von Ingo von Münch, vol. II, Stuttgart 1974, p. 301. Source of English translation: The Bulletin, vol. -

Berlin, Germany Development

Higher Higher Education in Regional and City Development Education Higher Education in Regional and City Berlin, Germany Development in Berlin is a creative city attracting talent from around the world. The Berlin Senate has Regional Berlin, Germany made great strides in developing innovation as a pillar of its economy. But challenges remain: there is long-term unemployment, a low absorptive capacity in small and medium-sized enterprises and a large migrant population that lags behind in educational and and labour market outcomes. City How can Berlin’s higher education institutions capitalise on their long tradition of Development professionally relevant learning and research to transform social, economic and environmental challenges into assets and opportunities? What incentives are needed to improve higher education institutions´ regional and local orientation? This publication explores a range of helpful policy measures and institutional reforms to Berlin, Germany mobilise higher education for Berlin’s development. It is part of the series of the OECD reviews of Higher Education in Regional and City Development. These reviews help mobilise higher education institutions for economic, social and cultural development of cities and regions. They analyse how the higher education system impacts upon regional and local development and bring together universities, other higher education institutions and public and private agencies to identify strategic goals and to work towards them. The full text of this book is available on line via this link: www.sourceoecd.org/education/97892640898467 Those with access to all OECD books on line should use this link: www.sourceoecd.org/97892640898467 SourceOECD is the OECD’s online library of books, periodicals and statistical databases. -

THE BERLIN CRISIS of 1961 the Origins and Management of a Crisis

THE BERLIN CRISIS OF 1961 The Origins and Management of a Crisis David G. Coleman Submitted as partial requirement for the degree of B.A. Honours, The University of Queensland 1995 I declare that this thesis is my own work and has not been submitted ui any form for another degree or diploma at any university or other institute of tertiary education. Information derived from the published or unpubhshed work of others has been acknowledged and a Hst of references is given. David G. Coleman October 1995 A cknowledgement I would like to thank Dr. Joseph M. Siracusa for assistance in the preparation of this thesis. His guidance and insights into United States foreign policy have been greatly appreciated. Contents CONTENTS Preface 1 Chapter One The Partition of Germany Chapter Two Eisenhower and Berlin 23 Chapter Three The Crisis of 1961: January - July 40 Chapter Four The Crisis of 1961: Resolution 54 Conclusion 69 Bibliography 74 Maps Partition of Germany 16 The Berlin Wall 57 Preface PREFACE In December 1961, former President Dwight D. Eisenhower reflected that "Berlin is not so much a beleaguered city or threatened city as it is a symbol - for the West, of principle, of good faith, of determination; for the Soviets, a thorn in their flesh, a wound to their pride, an impediment to their designs."' He had played an integral part in the development of the German situation, firstly as Supreme Commander of the AlHed Forces in Europe, and later as President of the United States. During this period Beriin was one issue around which many others were gathered. -

Reinventing Traditionalism: the Influence of Critical Reconstruction on the Shape of Berlin’S Friedrichstadt

Reinventing Traditionalism: The Influence of Critical Reconstruction on the Shape of Berlin’s Friedrichstadt by Naraelle Barrows Senior Thesis Art History, Comparative History of Ideas University of Washington Introduction The building of the Berlin Wall in 1961 transformed the central neighborhood of Mitte, formerly the heart of the Prussian and Weimar capital, into an area on the outskirts of both East and West Berlin. The southern part of this neighborhood, called the Friedrichstadt after its builder Friedrich Wilhelm I, was split almost perfectly in half by the new boundary (see map, Figure 1, next page). Thus relegated to the borderlands of both East and West, the Friedrichstadt remained largely untouched and dilapidated for the bulk of Germany’s separation. In the 1980s a few building projects were pursued by both sides, but the biggest change came after German reunification and the Berlin Wall’s removal in 1990. The decision a year later to move the capital back to Berlin from Bonn made Mitte once again the center of the capital of Germany, and the whole city experienced a tumultuous period of rebuilding, earning Berlin the title of “biggest construction site in Europe.”1 This flood of building projects and real estate speculation in the early 1990s quickly caused city planners to recognize that an overall guiding vision was needed if Berlin was to become anything other than a playground for ambitious architects. To provide a set of guidelines for rebuilding, Berlin planners and a close-knit circle of theorists and architects implemented, using various political channels, the approach of “Critical Reconstruction.” Developed during the previous two decades by theorist and architect Josef Paul Kleihues, this planning concept advocates a combination of new and restored buildings to create an urban environment that draws on historic forms in order to embody, according to its proponents, the true essence of the 1 From 1949 to 1990, Berlin served as the capital of East Germany. -

The Constitutional Law of German Unification , 50 Md

Maryland Law Review Volume 50 | Issue 3 Article 3 The onsC titutional Law of German Unification Peter E. Quint Follow this and additional works at: http://digitalcommons.law.umaryland.edu/mlr Part of the International Law Commons Recommended Citation Peter E. Quint, The Constitutional Law of German Unification , 50 Md. L. Rev. 475 (1991) Available at: http://digitalcommons.law.umaryland.edu/mlr/vol50/iss3/3 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by the Academic Journals at DigitalCommons@UM Carey Law. It has been accepted for inclusion in Maryland Law Review by an authorized administrator of DigitalCommons@UM Carey Law. For more information, please contact [email protected]. m@ :::z::::: :::::: ::: . : ' " ' ... 0... .. = . ... ..... .. .... ..... -'.'. :. ~......>.. -.., ....... .. ...... _ .- :i..:""- ............ .:!........ :. !!:"° S. ... .. .. MARYLAND LAW REVIEW VOLUME 50 1991 NUMBER 3 © Copyright Maryland Law Review, Inc. 1991 Articles THE CONSTITUTIONAL LAW OF GERMAN UNIFICATION PETER E. QUINT* TABLE OF CONTENTS MAP: GERMANY, 1945 INTRODUCTION .............................................. 476 I. UNION AND DISUNION IN GERMAN HISTORY ............. 478 II. THE LEGAL STATUS OF GERMANY, 1945-1989 .......... 480 III. POLITICAL REVOLUTION IN THE GDR, 1989-1990 ....... 483 IV. CONSTITUTIONAL REFORM IN THE GDR, 1989-1990 .... 488 A. Background: The 1968/74 Constitution of the GDR ... 488 B. Proposalsfor a New GDR Constitution-The Round Table Draft ....................................... 493 C. Amending the GDR Constitution-The Old Volkskammer and the Modrow Government ........................ 496 Copyright © 1991 by Peter E. Quint. * Professor of Law, University of Maryland. A.B., Harvard University, 1961; LL.B., 1964; Diploma in Law, Oxford University, 1965. For valuable comments on earlier drafts of this article I am grateful to Winfried Brugger, Thomas Giegerich, Eckart Klein, Alexander Reuter, William Reynolds, Edward Tomlinson, and Giinther Wilms.