Reinventing Traditionalism: the Influence of Critical Reconstruction on the Shape of Berlin’S Friedrichstadt

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Hocquet (Centre Max Weber, Université Jean Monnet - Saint-Étienne) [email protected]

Urbanities, Vol. 3 · No 2 · November 2013 © 2013 Urbanities The Exhibition of Communist Objects and Symbols in Berlin’s Urban Landscape as Alternative Narratives of the Communist Past Marie Hocquet (Centre Max Weber, Université Jean Monnet - Saint-Étienne) [email protected] The objective of this article is to investigate the different approaches at play in the material and symbolic production of the urban space through the study of the transformations of the East-Berlin urban landscape since the German reunification. I will show how the official accounts of the ex-GDR have crystallised in the Berlin urban space through the construction of a negative heritage. I will then focus on how the increase in historic tourism in the capital has contributed to the emergence of legible micro-accounts related to the local communist past in the urban space that compete with the official interpretations of this past. Key words: Berlin, symbolism, communism, heritage Introduction Urban space can be considered as a privileged place where one can observe the work of self- definition undertaken by societies. This is because human beings take their place in a physical environment by materialising their being-in-the-world. The urban landscape is defined by Mariusz Czepczyński as a ‘visible and communicative media through which thoughts, ideas and feelings, as well as powers and social constructions are represented in a space’ (Czepczyński 2010: 67). In the process outlined above, the narrativisation of the past and its inscription in the urban space is a phenomenon of primary importance. Our cities’ landscapes are linked to memory in a dynamic process which constantly urges societies to visualise themselves, to imagine the future and to represent themselves in it. -

Bankettmappe Konferenz Und Events

Conferences & Events Conferences & Events Discover the “new center of Berlin” - located in the heart of Germany’s capital between “Potsdamer Platz” and “Alexanderplatz”. The Courtyard by Marriott Berlin City Center offers excellent services to its international clientele since the opening in June 2005. Just a short walk away, you find a few of Berlin’s main attractions, such as the famous “Friedrichstrasse” with the legendary Checkpoint Charlie, the “Gendarmenmarkt” and the “Nikolaiviertel”. Experience Berlin’s fascinating and exciting atmosphere and discover an extraordinary hotel concept full with comfort, elegance and a colorful design. Hotel information Room categories Hotel opening: June 2005 Total number: 267 Floors: 6 Deluxe: 118 Twin + 118 King / 26 sqm Non smoking rooms: 1st - 6th floor/ 267 rooms Superior: 21 rooms / 33 sqm (renovated in 2014) Junior Suite: 6 rooms / 44 sqm Conference rooms: 11 Suite: 4 rooms / 53 sqm (renovated in 2016) Handicap-accessible: 19 rooms Wheelchair-accessible: 5 rooms Check in: 03:00 p.m. Check out: 12:00 p.m. Courtyard® by Marriott Berlin City Center Axel-Springer-Strasse 55, 10117 Berlin T +49 30 8009280 | marriott.com/BERMT Room facilities King bed: 1.80 m x 2 m Twin bed: 1.20 m x 2 m All rooms are equipped with an air-conditioning, Pay-TV, ironing station, two telephones, hair dryer, mini-fridge, coffee and tea making facilities, high-speed internet access and safe in laptop size. Children Baby beds are free of charge and are made according to Marriott standards. Internet Wireless internet is available throughout the hotel and free of charge. -

A Foreign Affair (1948)

Chapter 3 IN THE RUINS OF BERLIN: A FOREIGN AFFAIR (1948) “We wondered where we should go now that the war was over. None of us—I mean the émigrés—really knew where we stood. Should we go home? Where was home?” —Billy Wilder1 Sightseeing in Berlin Early into A Foreign Affair, the delegates of the US Congress in Berlin on a fact-fi nding mission are treated to a tour of the city by Colonel Plummer (Millard Mitchell). In an open sedan, the Colonel takes them by landmarks such as the Brandenburg Gate, the Reichstag, Pariser Platz, Unter den Lin- den, and the Tiergarten. While documentary footage of heavily damaged buildings rolls by in rear-projection, the Colonel explains to the visitors— and the viewers—what they are seeing, combining brief factual accounts with his own ironic commentary about the ruins. Thus, a pile of rubble is identifi ed as the Adlon Hotel, “just after the 8th Air Force checked in for the weekend, “ while the Reich’s Chancellery is labeled Hitler’s “duplex.” “As it turned out,” Plummer explains, “one part got to be a great big pad- ded cell, and the other a mortuary. Underneath it is a concrete basement. That’s where he married Eva Braun and that’s where they killed them- selves. A lot of people say it was the perfect honeymoon. And there’s the balcony where he promised that his Reich would last a thousand years— that’s the one that broke the bookies’ hearts.” On a narrative level, the sequence is marked by factual snippets infused with the snide remarks of victorious Army personnel, making the fi lm waver between an educational program, an overwrought history lesson, and a comedy of very dark humor. -

He Big “Mitte-Struggle” Politics and Aesthetics of Berlin's Post

Martin Gegner he big “mitt e-struggl e” politics and a esth etics of t b rlin’s post-r nification e eu urbanism proj ects Abstract There is hardly a metropolis found in Europe or elsewhere where the 104 urban structure and architectural face changed as often, or dramatically, as in 20 th century Berlin. During this century, the city served as the state capital for five different political systems, suffered partial destruction pós- during World War II, and experienced physical separation by the Berlin wall for 28 years. Shortly after the reunification of Germany in 1989, Berlin was designated the capital of the unified country. This triggered massive building activity for federal ministries and other governmental facilities, the majority of which was carried out in the old city center (Mitte) . It was here that previous regimes of various ideologies had built their major architectural state representations; from to the authoritarian Empire (1871-1918) to authoritarian socialism in the German Democratic Republic (1949-89). All of these époques still have remains concentrated in the Mitte district, but it is not only with governmental buildings that Berlin and its Mitte transformed drastically in the last 20 years; there were also cultural, commercial, and industrial projects and, of course, apartment buildings which were designed and completed. With all of these reasons for construction, the question arose of what to do with the old buildings and how to build the new. From 1991 onwards, the Berlin urbanism authority worked out guidelines which set aesthetic guidelines for all construction activity. The 1999 Planwerk Innenstadt (City Center Master Plan) itself was based on a Leitbild (overall concept) from the 1980s called “Critical Reconstruction of a European City.” Many critics, architects, and theorists called it a prohibitive construction doctrine that, to a certain extent, represented conservative or even reactionary political tendencies in unified Germany. -

16 November 2018 in Bonn, Germany

United Nations/Germany High Level Forum: The way forward after UNISPACE+50 and on Space2030 13 – 16 November 2018 in Bonn, Germany USEFUL INFORMATION FOR PARTICIPANTS Content: 1. Welcome to Bonn! ..................................................................................................................... 2 2. Venue of the Forum and Social Event Sites ................................................................................. 3 3. How to get to the Venue of the Forum ....................................................................................... 4 4. How to get to Bonn from International Airports ......................................................................... 5 5. Visa Requirements and Insurance .............................................................................................. 6 6. Recommended Accommodation ............................................................................................... 6 7. General Information .................................................................................................................. 8 8. Organizing Committe ............................................................................................................... 10 Bonn, Rhineland Germany Bonn Panorama © WDR Lokalzeit Bonn 1. Welcome to Bonn! Bonn - a dynamic city filled with tradition. The Rhine and the Rhineland - the sounds, the music of Europe. And there, where the Rhine and the Rhineland reach their pinnacle of beauty lies Bonn. The city is the gateway to the romantic part of -

Berlin - Wikipedia

Berlin - Wikipedia https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Berlin Coordinates: 52°30′26″N 13°8′45″E Berlin From Wikipedia, the free encyclopedia Berlin (/bɜːrˈlɪn, ˌbɜːr-/, German: [bɛɐ̯ˈliːn]) is the capital and the largest city of Germany as well as one of its 16 Berlin constituent states, Berlin-Brandenburg. With a State of Germany population of approximately 3.7 million,[4] Berlin is the most populous city proper in the European Union and the sixth most populous urban area in the European Union.[5] Located in northeastern Germany on the banks of the rivers Spree and Havel, it is the centre of the Berlin- Brandenburg Metropolitan Region, which has roughly 6 million residents from more than 180 nations[6][7][8][9], making it the sixth most populous urban area in the European Union.[5] Due to its location in the European Plain, Berlin is influenced by a temperate seasonal climate. Around one- third of the city's area is composed of forests, parks, gardens, rivers, canals and lakes.[10] First documented in the 13th century and situated at the crossing of two important historic trade routes,[11] Berlin became the capital of the Margraviate of Brandenburg (1417–1701), the Kingdom of Prussia (1701–1918), the German Empire (1871–1918), the Weimar Republic (1919–1933) and the Third Reich (1933–1945).[12] Berlin in the 1920s was the third largest municipality in the world.[13] After World War II and its subsequent occupation by the victorious countries, the city was divided; East Berlin was declared capital of East Germany, while West Berlin became a de facto West German exclave, surrounded by the Berlin Wall [14] (1961–1989) and East German territory. -

6Th CGIAR System Council Meeting Logistics Information

6th CGIAR System Council Meeting Logistics Information Hosted by Germany at Humboldt Carré, Berlin, Germany 16‐17 May 2018 Humboldt Carré Conference Center Behrenstraße 42, 10117 Berlin, Germany Phone number: +49 30 2014485125 Web site: http://www.humboldtcarre.de/en If you have any questions or require assistance whilst attending the meeting or the side events, please contact Ms. Victoria Pezzi: +33 6 30 83 73 37 ‐ [email protected] 6th CGIAR System Council Meeting Logistics Information Dear System Council Members, Delegated Members, Active Observers and Invited Guests, We are pleased to invite you to the forthcoming sixth meeting of the CGIAR System Council. The information in this document is designed to facilitate your attendance at the meeting and your visit to Berlin. Contents 1. Schedule of Events ............................................................................................................ 2 2. Pre-Meeting Support and Arrangements ...................................................................... 3 2.1. Meeting materials and pre-meeting Calls ............................................................... 3 2.2. Accommodation ........................................................................................................... 3 3. Arrival and Transportation ................................................................................................ 4 3.1. Arrival at the airport and directions to the city center ........................................... 4 3.2. Directions to Humboldt Carré (SC6 venue) -

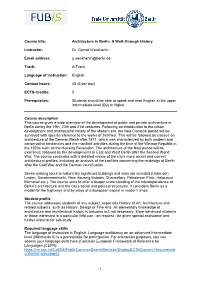

Architecture in Berlin. a Walk Through History Instructor

Course title: Architecture in Berlin. A Walk through History Instructor: Dr. Gernot Weckherlin Email address: [email protected] Track: A-Track Language of instruction: English Contact hours: 48 (6 per day) ECTS-Credits: 5 Prerequisites: Students should be able to speak and read English at the upper intermediate level (B2) or higher. Course description This course gives a wide overview of the development of public and private architecture in Berlin during the 19th, 20th and 21st centuries. Following an introduction to the urban development and architectural history of the Modern era, the Neo-Classical period will be surveyed with special reference to the works of Schinkel. This will be followed by classes on architecture of the German Reich after 1871, which was characterized by both modern and conservative tendencies and the manifold activities during the time of the Weimar Republic in the 1920s such as the Housing Revolution. The architecture of the Nazi period will be examined, followed by the developments in East and West Berlin after the Second World War. The course concludes with a detailed review of the city’s more recent and current architectural profiles, including an analysis of the conflicts concerning the re-design of Berlin after the Cold War and the German reunification. Seven walking tours to historically significant buildings and sites are included (Unter den Linden, Gendarmenmarkt, New Housing Estates, Chancellory, Potsdamer Platz, Holocaust Memorial etc.). The course aims to offer a deeper understanding of the interdependence of Berlin’s architecture and the city’s social and political structures. It considers Berlin as a model for the highways and by-ways of a European capital in modern times. -

History and Memory in International Youth Meetings Authors Ludovic Fresse, Rue De La Mémoire Ines Grau, Aktion Sühnezeichen Friedensdienste E.V

Pedagogical Vade mecum History and memory in international youth meetings Authors Ludovic Fresse, Rue de la Mémoire Ines Grau, Aktion Sühnezeichen Friedensdienste e.V. Editors Sandrine Debrosse-Lucht and Elisabeth Berger, FGYO Manuscript coordination Pedagogical Vade mecum Corinna Fröhling, Cécilia Pinaud-Jacquemier and Annette Schwichtenberg, FGYO Graphic design Antje Welde, www.voiture14.com History and memory We would like to thank the members of the working group “How can we take a multi-perspective approach to history in youth meetings while meeting the goals of peace education and of a reinforced awareness of European citizenship?”: in international Claire Babin, Aktion Sühnezeichen Friedensdienste e.V. Konstantin Dittrich, Volksbund Deutsche Kriegsgräberfürsorge e.V. Ludovic Fresse, Rue de la Mémoire youth meetings Ines Grau, Aktion Sühnezeichen Friedensdienste e.V. Claire Keruzec, Aktion Sühnezeichen Friedensdienste e.V. Bernard Klein, Centre international Albert Schweizer, Volksbund Deutsche Kriegsgräberfürsorge e.V. Jörn Küppers, Interju e.V. Julie Morestin, Volksbund Deutsche Kriegsgräberfürsorge e.V. Johanna Reyer Hannah Röttele, Universität Göttingen Torsten Rutinowski, Transmedia Michael Schill, Europa-Direkt e.V. Richard Stock, Centre européen Robert Schuman Garance Thauvin Dorothée Malfoy-Noël, OFAJ / DFJW Karin Passebosc, OFAJ / DFJW for their contributions. Translation Claire Elise Webster and Jocelyne Serveau Copyright © OFAJ / DFJW, 2016, 2019 Print Siggset ISBN 978-2-36924-004-4 4 5 PREFACE The French “Rue de la Mémoire” association is a pedagogical laboratory Commemorations surrounding the Centenary of the First World War have shown how dedicated to working with history and memory as vectors of active closely historical recollection and political activity are linked. This is especially true with citizenship. -

Sapphire Residence Brilliant-Living in Berlin-Mitte Landmark Architecture with Radical New Angles

SCHWARTZKOPFFSTRASSE 1A 10115 BERLIN-MITTE SAPPHIRE RESIDENCE BRILLIANT-LIVING IN BERLIN-MITTE LANDMARK ARCHITECTURE WITH RADICAL NEW ANGLES A modern-living gem in Berlin’s central borough of Mitte: On roughly 103 sqm, the SAPPHIRE RESIDENCE apartment awaits you in the spectacular residential building of the same name, SAPPHIRE – designed by celebrated architect Daniel Libeskind. Even from afar, the many different hues of blue and silver of the shiny futuristic façade will stun you as they combine with the building’s exceptional lines and its extraordinary language of form. And this in a central location close to the city’s heartbeat where the ground-breaking architecture perfectly complements the urban liveability of Berlin. Experience landmark living at SAPPHIRE RESIDENCE. AN ARCHITECT OF GLOBAL RENOWN: DANIEL LIBESKIND To date, the SAPPHIRE is the first and only residential building in Germany designed by Daniel Libeskind, an architect of international standing. Which makes REFERENCES it a very special brainchild of this visionary who is well known in town for extraordinary structures such as the Jewish Museum Berlin. Libeskind’s trend- setting apartment building makes innovative use of material that could be the wave of the future in housing. For one thing, the exterior façade of the SAPPHIRE is fitted with self-cleaning ceramic- titanium tiles – made by hand specifically for this building. Uniqueness are also the claim to fame of the SAPPHIRE RESIDENCE, whose fit-out features bear has the master’s tell-tale handwriting. Jüdisches Museum Berlin Royal Ontario Museum, Toronto, Kanada Contemporary Jewish Museum, San Francisco, USA CREATIVE, EXKLUSIVE, NON-CONFORMIST A neighbourhood walk around the SAPPHIRE RESIDENCE will take you down Chausseestrasse to the River Spree, past stately government buildings like the BND headquarters or the Natural History Museum with Where the hip scene dines: Grill Royal Due Fratelli: Italian specialities, greatly favoured by night-hawks its famous dinosaur exhibits. -

Le Corbusier in Berlin, 1958: the Universal and the Individual in the Unbuilt City

DOI: http://dx.doi.org/10.4995/LC2015.2015.921 Le Corbusier in Berlin, 1958: the universal and the individual in the unbuilt city M. Oliveira Eskinazi Faculdade de Arquitetura e Urbanismo, Universidade Federal do Rio de Janeiro. Programa de Pós-Graduação em Urbanismo, Universidade Federal do Rio de Janeiro Abstract: Among several urban plans designed for Berlin, we find Le Corbusier`s project for the Hauptstadt Berlin 1958 competition, which aimed at thinking the reconstruction of the city center destroyed in the II World War. Corbusier`s relation with Berlin dates back to 1910, when he arrives at the city to work at Peter Behrens` office. So, for him, the plan for Berlin was a rare opportunity to develop ideas about the city that provided one of the largest contributions to his urban design education, and also to develop ideas he formulated forty years before for Paris` center. Besides that, this project was developed almost simultaneously with CIAM`s crises and dissolution, which culminated in the 50`s with the consequent appearance of Team 10. At that moment Corbusier`s universalist approach to urbanism starts to be challenged by CIAM`s young generation, which had a critical approach towards the design methods inherited from the previous generation, associated with CIAM`s foundational moment. From the beginning of the 50`s on, this new generation balances the universalist ideals inherited from the previous generation with individualist ones they identified as necessary to face the new post war reality. Thus, the main goal of this paper is to analyse Corbusier’s design for Berlin and question whether he, at an already mature point of his career, was proposing a plan that answered only the questions that were important to CIAM and to the canonical principles of modern architecture, or if he had also addressed those that belonged to the new generation and Team 10`s agenda, both of them present in the debates of the moment, largely identified as a transitional period. -

Berlin Is the Capital of Germany and Was the Capital of the Former Kingdom of Prussia

Berlin is the capital of Germany and was the capital of the former kingdom of Prussia. After World War II, Berlin was divided, and in 1961, the Berlin Wall was built. But the wall fell in 1989, and the country became one again in 1990. ©2015 Bonnie Rose Hudson WriteBonnieRose.com ////////////////////////////////////////////////////// ////////////////////////////////////////////////////// ////////////////////////////////////////////////////// ////////////////////////////////////////////////////// ////////////////////////////////////////////////////// ////////////////////////////////////////////////////// ////////////////////////////////////////////////////// ////////////////////////////////////////////////////// ////////////////////////////////////////////////////// ////////////////////////////////////////////////////// ////////////////////////////////////////////////////// ////////////////////////////////////////////////////// ////////////////////////////////////////////////////// ©2015 Bonnie Rose Hudson WriteBonnieRose.com Cologne/is/in/a/region/of/Germany/called/the/ Rhineland./Its/biggest/and/most/famous//////// building/is/the/Cologne/Cathedral,/a/giant///// church/that/stretches/515/feet/high!/Inside///// the/church/you/can/find/many/beautiful//////// pieces/of/art,/some/more/than/500/years/old./ Cologne/is/in/a/region/of/Germany/called/the/ Rhineland./Its/biggest/and/most/famous//////// building/is/the/Cologne/Cathedral,/a/giant///// church/that/stretches/515/feet/high!/Inside///// the/church/you/can/find/many/beautiful////////