Le Corbusier in Berlin, 1958: the Universal and the Individual in the Unbuilt City

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

He Big “Mitte-Struggle” Politics and Aesthetics of Berlin's Post

Martin Gegner he big “mitt e-struggl e” politics and a esth etics of t b rlin’s post-r nification e eu urbanism proj ects Abstract There is hardly a metropolis found in Europe or elsewhere where the 104 urban structure and architectural face changed as often, or dramatically, as in 20 th century Berlin. During this century, the city served as the state capital for five different political systems, suffered partial destruction pós- during World War II, and experienced physical separation by the Berlin wall for 28 years. Shortly after the reunification of Germany in 1989, Berlin was designated the capital of the unified country. This triggered massive building activity for federal ministries and other governmental facilities, the majority of which was carried out in the old city center (Mitte) . It was here that previous regimes of various ideologies had built their major architectural state representations; from to the authoritarian Empire (1871-1918) to authoritarian socialism in the German Democratic Republic (1949-89). All of these époques still have remains concentrated in the Mitte district, but it is not only with governmental buildings that Berlin and its Mitte transformed drastically in the last 20 years; there were also cultural, commercial, and industrial projects and, of course, apartment buildings which were designed and completed. With all of these reasons for construction, the question arose of what to do with the old buildings and how to build the new. From 1991 onwards, the Berlin urbanism authority worked out guidelines which set aesthetic guidelines for all construction activity. The 1999 Planwerk Innenstadt (City Center Master Plan) itself was based on a Leitbild (overall concept) from the 1980s called “Critical Reconstruction of a European City.” Many critics, architects, and theorists called it a prohibitive construction doctrine that, to a certain extent, represented conservative or even reactionary political tendencies in unified Germany. -

Curriculum Vitae for Professor Peter Blundell Jones

Curriculum vitae for Professor Peter Blundell Jones. Qualifications: RIBA parts 1&2. A.A.Diploma. M.A.Cantab. Career Summary Born near Exeter, Devon, 4/1/49. Architectural education: Architectural Association, London, 1966-72. October 1972/ July 73: Employed by Timothy Rendle, ARIBA, in London, as architectural assistant. September 1973/ June 1974: Wrote book on Hans Scharoun, published by Gordon Fraser. September 1974/ June 1975: Part-time tutor at Architectural Association. July 1975/ May 1977: In Devon as designer and contractor for Round House at Stoke Canon near Exeter, published in The Architectural Review and now included in Pevsner’s Buildings of England. 1977/ 78: free-lance lecturer and architectural journalist. October 1978/ September 1983: Full time post as Assistant Lecturer in architecture at Cambridge University. Duties included lecture series in architectural theory, studio teaching, and examining. 1983/ 87: visiting lecturer at Cambridge University and Polytechnic of North London, free- lance journalist and critic writing for Architects’ Journal and Architectural Review, research on German Modernism focusing on Hugo Häring. Member of CICA, the international critics organisation. September 1988/ July 1994: full time post as Principal Lecturer in History and Theory at South Bank Polytechnic, later South Bank University. Visiting lecturer in other schools. External examiner 1988-91 to Hull school of architecture, and subsequently to Queen’s University Belfast. Readership at South Bank University conferred December 1992. Since August 1994: Professor of Architecture at the School of Architecture, University of Sheffield, with responsibility for Humanities. Member of the executive group, organiser and contributor to lecture courses and several external lecture series, reorganiser of the Diploma School in the late 1990s and studio leader, tutor of dissertations at both undergraduate and Diploma levels: heavy commitment in recent years to the humanities PhD programme. -

Hans Scharoun and Frank Gehry

1997 ACSA EUROPEAN CONFERENCE t BERLIN HANS SCHAROUN AND FRANK GEHRY TWO 61CONOCLASTS99SEEKING FORM FOR THE MODERN INSTITUTION GUNTER DITTMAR University of Minnesota Introduction support" he received "fromthe artists, which I was not Hans Scharoun and Frank Gehry, two architects gettingfrom the architects. The architects thought I was seemingly very distant in time, place and culture, weird."3 nevertheless, show striking parallels and similarities in The influence of art seems readily apparent in the their careers, their work, and their approach to dynamic, sculptural quality of their work. It is this very architecture. More than a generation apart and practicing quality, however, that is responsible for a great deal ofthe at radically different times and locations - Scharoun misunderstanding and misrepresentation by critics, before and after World War 11, mostly in Berlin, Gehry professional peers, theorists and historians. Using from the sixties to the present - the context and simplistic, descriptive labels,the work is characterized as circumstances withinwhich they developed their mature "expressionist"in Scharoun's case, or "neo-expressionist" architectural work, and the issues they confronted,were in Gehry's. Implicit is the notion that it is "irrational," remarkably similar. '(formalistic,"lacking any intellectual merit or rigor, the Scharoun, in his formative years during the two wars, result of self-indulgent,personal expression; that it is all played an active role in the avant-garde movement that, about style and not substance; -

The 1963 Berlin Philharmonie – a Breakthrough Architectural Vision

PRZEGLĄD ZACHODNI I, 2017 BEATA KORNATOWSKA Poznań THE 1963 BERLIN PHILHARMONIE – A BREAKTHROUGH ARCHITECTURAL VISION „I’m convinced that we need (…) an approach that would lead to an interpretation of the far-reaching changes that are happening right in front of us by the means of expression available to modern architecture.1 Walter Gropius The Berlin Philharmonie building opened in October of 1963 and designed by Hans Scharoun has become one of the symbols of both the city and European musical life. Its character and story are inextricably linked with the history of post-war Berlin. Construction was begun thanks to the determination and un- stinting efforts of a citizens initiative – the Friends of the Berliner Philharmo- nie (Gesellschaft der Freunde der Berliner Philharmonie). The competition for a new home for the Berlin Philharmonic Orchestra (Berliner Philharmonisches Orchester) was won by Hans Scharoun whose design was brave and innovative, tailored to a young republic and democratic society. The path to turn the design into reality, however, was anything but easy. Several years were taken up with political maneuvering, debate on issues such as the optimal location, financing and the suitability of the design which brought into question the traditions of concert halls including the old Philharmonie which was destroyed during bomb- ing raids in January 1944. A little over a year after the beginning of construction the Berlin Wall appeared next to it. Thus, instead of being in the heart of the city, as had been planned, with easy access for residents of the Eastern sector, the Philharmonie found itself on the outskirts of West Berlin in the close vicinity of a symbol of the division of the city and the world. -

Potsdamer Platz & Tiergarten

©Lonely Planet Publications Pty Ltd 111 Potsdamer Platz & Tiergarten POTSDAMeR PLATZ | KuLTuRFORuM | TIeRGARTeN | DIPLOMATeNvIeRTeL Neighbourhood Top Five 1 Feeling your spirit soar zling a cold one in a beer to the Nazis and often paid while studying an Aladdin’s garden. the ultimate price at the cave of Old Masters at the 3 Stopping for coffee and Gedenkstätte deutscher magnificent Gemälde- people-watching beneath widerstand (p121). galerie (p116). the magnificent canopy of 5 Catching Europe’s fastest 2 Getting lost amid the the svelte glass-and-steel lift to the panoramapunkt lawns, trees and leafy sony center (p113). (p114) to admire Berlin’s paths of the Tiergarten 4 Learning about the impressive cityscape. park (p125), followed by guz- brave people who stood up Platz der Republik Paulstr er Jo str 6666666Spree Riv hn-Fost 66e Scheidemann er -Dulles-Al l e 000 eg 000 w 000Pariser ee 000 pr 000Platz S 000 Grosser Strasse des 17 Juni T 222 Stern i Bellevueallee e 222 r 6666666666g 222 TIERGARTEN a r 222Holocaust t e 222r Memorial Hofjägerallee n t t 222 s u n rt n e e b l ##÷ Luiseninsel r E 2 Rousseauinsel ést Lenn Bellevuestr 66666666Vossstr Potsdamer str Tiergarten Platz K 3##æ l #æ r i n r Str t dame g ts #æ s Po 5# r e e l #â# l h 1 S ü ö t S t f igi re S e #æ sm 4# und s r Hiroshimastr e s s tr m t dt-Str 666666r 6 ey a d-H n V- La n nd s er w r t f e t u h Stauffenbergstr r ow r R S ütz kan ei L al berger Ufer ch r öne p e Sch ie n r ts e Lützowstr t c Linkstr h h S u t fe ö er r K n i KurfürstenstrSchillstr h 666t 0 500 m en e# 0 0.25 miles G 6 For more detail of this area, see map p316 A 112 Lonely Planet’s Top Tip Explore: Potsdamer Platz & Tiergarten From July to September, the Despite the name, Potsdamer Platz is not just a square but lovely thatch-roofed Tee- Berlin’s newest quarter, born in the ’90s from terrain once haus im englischen Garten bifurcated by the Berlin Wall. -

Eberhard Syring: Hans Scharoun - Architekt Der Moderne Mit Bremer Wurzeln

Eberhard Syring: Hans Scharoun - Architekt der Moderne mit Bremer Wurzeln Hans Scharoun um 1930 und um 1960 A. Einleitung Eberhard Syring: Hans Scharoun - Architekt der Moderne mit Bremer Wurzeln Was ist moderne Architektur? A. Einleitung Eberhard Syring: Hans Scharoun - Architekt der Moderne mit Bremer Wurzeln Walter Gropius, Bauhausneubau in Dessau 1925-26 … muss man es umschreiten. A. Einleitung Eberhard Syring: Hans Scharoun - Architekt der Moderne mit Bremer Wurzeln Henry van de Velde, Kunstakademie Weimar, 1904-11 Walter Gropius, Bauhausneubau in Dessau 1925-26 Das Bauhaus begann vor hundert Jahren in einem Jugendstilbau A. Einleitung Eberhard Syring: Hans Scharoun - Architekt der Moderne mit Bremer Wurzeln Historismus Jugendstil Reformarchitektur/ Heimatschutzstil Expressionismus Neues Bauen Die Architektur durchlief zu Beginn des 20. Jhds einen Umbruch A. Einleitung Eberhard Syring: Hans Scharoun - Architekt der Moderne mit Bremer Wurzeln Historismus Jugendstil Historismus: Gerichtsgebäude Bremen, 1895 Jugendstil: Kunstakademie Weimar, 1904-11 Die Architektur durchlief zu Beginn des 20. Jhds einen Umbruch A. Einleitung Eberhard Syring: Hans Scharoun - Architekt der Modernen mit Bremer Wurzeln Historismus Reformarchitektur/ Heimatschutzstil Historismus: Gerichtsgebäude Bremen, 1895 Reformarchitektur: Neues Rathaus Bremen, 1913 Die Architektur durchlief zu Beginn des 20. Jhds einen Umbruch A. Einleitung Eberhard Syring: Hans Scharoun - Architekt der Modernen mit Bremer Wurzeln Historismus Expressionismus Historismus: Gerichtsgebäude -

RSO in Friedrichshain

RSO in Friedrichshain Richard-Sorge-Straße, 10249 Berlin RSO in Friedrichshain from 4 Apartments, 12 Bedrooms Richard-Sorge-Straße, 10249 Berlin U-Bahn Frankfurter Tor 845€ S-Bahn Frankfurter Allee RSO is a collection of 3 identical apartments situated on top of each other, with 1 apartment in the same complex. They are wonderful 3 bedroom apartments with a very traditional Berlin design. The apartments being located in the same building gives you a great opportunity to meet a lot of people, and still maintain a great level of privacy. Available from March 10th Photos of other GoLiving Apartments 4 Apartments ‘Anmeldung’ possible 12 Bedrooms Free Events Utilities Included Fully Furnished High-Speed WiFi Household Supplies 110m² Each Balcony Kitchen Apartments 1, 2 and 3 in RSO 3 Identical Apartments Example Pictures Apartment 1, 2, 3 Single Bedroom 1 €1195 Highlight: Massive Room This room is one of the biggest that GoLiving has to offer. It is brightly lit and gives you a fantastic space to relax and work in. Photo of a similar GoLiving Room Fully Furnished Large Windows Lockable Doors Desk & Chair Weekly Cleaning High-Speed WiFi Utilities Included Lockable Doors 26m² 3 Identical Rooms Example Pictures Apartment 1, 2, 3 Single Bedroom 2 €1195 Highlight: Private Terrace This room with massive windows is full of light. It also comes with a private balcony that you can relax on in the summer months. Photo of a similar GoLiving Room Private Balcony Large Windows Weekly cleaning Desk & Chair Lockable doors Sheets & Linen Utilities Included High-Speed WiFi 22m² 3 Identical Rooms Example Pictures Apartment 1, 2, 3 Single Bedroom 3 €995 Highlight: Brightly lit room This room is a great space for an individual to relax in after work. -

Berlin: Stalins

Berlin: Stalins öra C-J CHARPENTIER FRANKFURTER ALLEE, som bytt namn flera gånger och bland annat hetat Stalin- allee, skär genom östra Berlin fram till Alexanderplatz – en gata präglad judisk köpenskap, blodiga uppror, krigets bomber, massmord och storskaliga arkitektoniska experi- ment. Följt av hämningslös mark- nadsekonomi efter Murens fall BERLIN: STALINS ÖRA är en unik dokumentation av gatans historia, kulturliv och politiska växlingar från gårdag till samtid – en spännande och i högsta grad läsvärd skildring signerad antro- pologen C-J Charpentier. C-J CHARPENTIER Berlin: Stalins öra Berättelser från en gata Stalins öra Omslagsbilden – Walter Womackas hyllning till lärare och utbildning, Haus des Lehrers, Karl-Marx-Allee © C-J Charpentier (2014) Foto: C-J Charpentier Förlag: Läs en bok Anträde Den här boken handlar om en vandring genom östra Berlin en tidig höstdag 2013, från Alt-Friedrichsfelde till Alexanderplatz längs den klassiska Frankfurter Allee, som en gång hette Stalin- allee och som sedan 1961 åter heter Frankfurter Allee i öster, medan den västra delen gavs namnet Karl-Marx-Allee. Det är en fantastisk gata, måhända den mest händelsemättade i Europa, ett stråk där brutal politik möter arkitektur, konst och litteratur. Men också en ”småfolkets inköpsboulevard” ‒ från sent 1800-tal till andra världskrigets bomber. Jag har varit i Berlin ungefär sextio gånger: före muren, under murtiden, natten då muren föll, och under de hittillsvarande åren som återförenad huvudstad. Som antropolog fascineras jag särskilt av den östra halvan, eftersom den – efter die Wende ‒ exemplifierar ett politiskt och ekonomiskt systemskifte, som på olika sätt präglat både människor och stadslandskap; något som jag länge tänkt dokumentera och skriva om. -

The Nordic Mauerpark Zeiss-Groß- BERLIN 65 Planetarium Discover Scandinavian Lifestyle

64 62 33 63 19 FREe 67 21 Flakturm 20 Humboldthain Prenzlauer Berg & Pankow The Nordic Mauerpark Zeiss-Groß- BERLIN 65 planetarium Discover Scandinavian Lifestyle Nordic Embassies Berlin 66 Kulturbrauerei Ernst- Thälmann- Mitte–North Denkmal Westhafen 63 61 35 Wasserturm Gedenkstätte 27 Berliner Mauer 28 25 29 23 26 34 24 Volksbühne 26 43 30 Naturkundemuseum 31 32 1 Velodrom 36 37 Neue Synagoge Hackesche Höfe Charité 22 33 Mitte–Central 36 Reichs- Friedrichshain BuNdes- tagsgebäude Kanzler- Berliner Amt Ensemble 44 45 41 10 Museumsinsel Brandenburger 72 Schloss Tor 40 Frankfurter Tor 80 Bellevue Haus der Berliner Strausberger Platz 74 34 Deutsches 73 Kulturen 46 dom der Welt Historisches 43 Museum 76 Siegessäule Gendarmenmarkt Denkmal für 42 Berliner die ermordeten 40 48 35 Juden Europas Schloss Technische Universität Berlin 38 2 47 81 Potsdamer 63 Charlottenburg Platz East Side Mitte–SOUTH Gallery 40 Tiergarten 16 14 25 43 31 Checkpoint 5 3 6 Charlie 77. 15 34 Nordic 11 Jüdisches Museum EmbaSsies 78 Berlin 43 35 Europa-Center 39 25 Bauhaus 7 Archiv 17 Kaiser-Wilhelm- 4 1 8 79 9 Gedächtnis-Kirche Tempodrom 68 43 75 Badeschiff 6 Oberbaumbrücke 71 Kaufhaus des Westens Molecule Man 52 57 69 Deutsches 50 Technikmuseum 58 kreuzberg 60 49 18 Hochbunker Pallasstraße 70 Wilmersdorf Neukölln 84 Klinikum 54 Am Urban 53 82 12 85 Schöneberg 56 55 59 51 33 13 25 89 Tempelhofer Feld Rathaus Gasometer Neukölln 83 John-F.-Kennedy-Platz 87 90 86 88 13. FORMER GRAVE RIKARD NORDRAAK Goddag, hyvää päivää, góðan daginn and 43. IITTALA 56. PALSTA WINE BAR This list is far from exhaustive but we 81. -

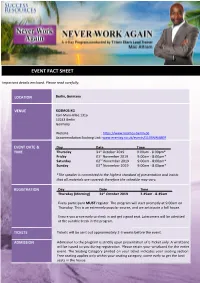

Event Fact Sheet

EVENT FACT SHEET Important details enclosed. Please read carefully. LOCATION Berlin, Germany KOSMOS KG VENUE Karl-Marx-Allee 131a 10243 Berlin Germany Website : https://www.kosmos-berlin.de Accommodation Booking Link: www.eventay.co.uk/events/1133NWABER EVENT DATE & Day Date Time TIME Thursday 31st October 2019 9:00am - 8:00pm* Friday 01st November 2019 9:00am - 8:00pm* Saturday 02nd November 2019 9:00am - 8:00pm* Sunday 03rd November 2019 9:00am - 8.00pm* *The speaker is committed to the highest standard of presentation and insists that all materials are covered; therefore the schedule may vary. REGISTRATION Day Date Time Thursday (Morning) 31st October 2019 7.45am - 8.45am Every participant MUST register. The program will start promptly at 9.00am on Thursday. This is an extremely popular course, and we anticipate a full house. Ensure you arrive early to check in and get a good seat. Latecomers will be admitted at the suitable break in the program. TICKETS Tickets will be sent out approximately 2-3 weeks before the event. ADMISSION Admission to the program is strictly upon presentation of E-Ticket only. A wristband will be issued to you during registration. Please retain your wristband for the entire event. The Seating Category printed on your ticket indicates your seating section. Free seating applies only within your seating category, come early to get the best seats in the house. TRANSLATION The following translations are available: German For QL members, please bring your QL nametag for registration; For Ala Carte and guest participants, a nametag will be issued during registration. -

Fachtagung „Die Pflegeausbildung Der Zukunft Gestalten – Die Neuen Rahmenpläne“ – 04

Fachtagung „Die Pflegeausbildung der Zukunft gestalten – Die neuen Rahmenpläne“ – 04. November 2019 Anfahrtsbeschreibung Aus dem Norden: Von der Autobahn A114 durchfahren bis zur B109 in Richtung Zentrum/Prenzlauer Berg auf der Prenzlauer Allee. Biegen Sie links ab in die Peterburger Straße (B96a) und nach ca. 3 km rechts in die Karl-Marx-Allee (B1). Nach 480 m erreichen Sie das Kosmos. Aus dem Osten: Von Autobahn A10 Abfahrt auf B1 (Zubringer zur Karl-Marx-Allee) Richtung Berlin Zentrum. Nach ca. 15 km erreichen Sie das Kosmos. Aus dem Westen: Fahren Sie die B5 Richtung Berlin und biegen rechts ab auf die Straße des 17. Juni (B5). Am Alexanderplatz biegen Sie nach rechts auf Karl-Marx-Allee (B1) ab und erreichen nach ca. 3 km das Kosmos. Aus dem Süden: Fahren Sie die B96 Richtung Berlin und biegen Sie nach ca. 14 km rechts ab in die Skalitzer Straße (B179). Nach ca. 6 km biegen Sie links ab in die Karl-Marx-Allee (B1) und erreichen nach ca. 480 m das Kosmos. Von Berlin-Tegel (TXL): Fahren Sie mit dem Bus TXL bis Beusselstraße. Steigen Sie um in die S-Bahnlinie S41 bis Frankfurter Allee. Von dort nehmen Sie die U5 in Richtung Alexanderplatz bis Frankfurter Tor. Von Berlin-Schönefeld (SXF): Nehmen Sie die S-Bahn S9 bis Frankfurter Allee. Dort steigen Sie in die U5 in Richtung Alexanderplatz um und fahren bis U-Bahnhof Frankfurter Tor. alternativ: Nehmen Sie den Regionalexpress RB 7 bis Ostbahnhof. Dort steigen Sie in den Bus 347 Richtung Stralau und fahren bis zur Haltestelle Weberwiese. -

1 STÄDTEBAULICHES GUTACHTEN Zur Untersuchung Der Schutzwürdigkeit Der Städtebaulichen Eigenart Als Voraus- Setzung Für Den E

Bezirk Friedrichshain-Kreuzberg Planungsgruppe WERKSTADT Gebiet an der Weberwiese Boxhagener Straße 16 Erhaltungsverordnung 10245 Berlin STÄDTEBAULICHES GUTACHTEN zur Untersuchung der Schutzwürdigkeit der städtebaulichen Eigenart als Voraus- setzung für den Erlass der Verordnung gem. § 172 Abs. 1 Satz 1 Nr. 1 Baugesetz- buch (BauGB) für das Gebiet an der Weberwiese Auftraggeber: Bezirksamt Friedrichshain-Kreuzberg von Berlin Abt. Planen, Bauen und Umwelt Stadtentwicklungsamt Yorkstraße 4-11 10965 Berlin Auftragnehmer: Planungsgruppe WERKSTADT Stadtplaner & Architekten Boxhagener Straße 16 10245 Berlin Februar 2016 1 Bezirk Friedrichshain-Kreuzberg Planungsgruppe WERKSTADT Gebiet an der Weberwiese Boxhagener Straße 16 Erhaltungsverordnung 10245 Berlin INHALTSVERZEICHNIS 1. PLANUNGSANLASS ............................................................................ 3 2. HISTORISCHE ENTWICKLUNG .......................................................... 7 2.1 Stadtentwicklungsetappen ...................................................................................... 7 2.1.1. Entstehungsgeschichte der Bebauung am „Frankfurter Tor“ ......................... 7 2.1.2. Wiederaufbaupläne nach dem 2. Weltkrieg – Wohnzelle Friedrichshain ..... 10 2.1.3 Planung und Bau der Wohnanlage Weberwiese und der Stalinallee ........... 14 2.1.4 Wohnkomplex Friedrichshain ....................................................................... 17 2.1.5 Wohnkomplex Straße der Pariser Kommune ............................................... 18 2.2 Grundsätzliche