The Impact of Public Employment: Evidence from Bonn

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

16 November 2018 in Bonn, Germany

United Nations/Germany High Level Forum: The way forward after UNISPACE+50 and on Space2030 13 – 16 November 2018 in Bonn, Germany USEFUL INFORMATION FOR PARTICIPANTS Content: 1. Welcome to Bonn! ..................................................................................................................... 2 2. Venue of the Forum and Social Event Sites ................................................................................. 3 3. How to get to the Venue of the Forum ....................................................................................... 4 4. How to get to Bonn from International Airports ......................................................................... 5 5. Visa Requirements and Insurance .............................................................................................. 6 6. Recommended Accommodation ............................................................................................... 6 7. General Information .................................................................................................................. 8 8. Organizing Committe ............................................................................................................... 10 Bonn, Rhineland Germany Bonn Panorama © WDR Lokalzeit Bonn 1. Welcome to Bonn! Bonn - a dynamic city filled with tradition. The Rhine and the Rhineland - the sounds, the music of Europe. And there, where the Rhine and the Rhineland reach their pinnacle of beauty lies Bonn. The city is the gateway to the romantic part of -

Germany - Solingen

Germany - Solingen The city of Solingen (population 165,000), situated on the river Wupper 30 km northeast of Cologne, was founded in 1374 and has grown famous as a blade manufacturing centre; becoming Sheffield's main competitor in the cutlery industry. The history of German sword making can be traced back to 1250. Solingen became established as a metalworking centre, not only because of the presence of iron ore and a plentiful supply of timber for charcoal and water to drive the grindstones but because the nearby town of Cologne was Germany's richest trading centre. Solingen was making fine quality sword blades in the fourteenth century and was contracted to sell all its swords and edged weapons to Cologne where handles were attached and the finished weapons sold. The grinders and temperers' guild was formed in 1401 and the sword smiths' guild in 1472. The cutlers' guild, with 82 cutlers, was mentioned for the first time in 1571 and the scissor smiths formed their guild in 1794. The first cutlery to be marked with the makers name (on the handle) - 1627 Hand forging was a skilled and time consuming process but fast striking mechanical hammers, driven by water wheels, were used in the 16th century to speed up the process of hand forging by around fivefold. Factories housing mechanical hammers were built on the rivers in and around Solingen to roughly forge sword blades before they were finished by hand forging. Although fear of unemployment caused the sword forging guild to argue that hand forged steel was better. Sheffield was still hand forging steel at this time but was using water to drive grinding wheels. -

Berlin Is the Capital of Germany and Was the Capital of the Former Kingdom of Prussia

Berlin is the capital of Germany and was the capital of the former kingdom of Prussia. After World War II, Berlin was divided, and in 1961, the Berlin Wall was built. But the wall fell in 1989, and the country became one again in 1990. ©2015 Bonnie Rose Hudson WriteBonnieRose.com ////////////////////////////////////////////////////// ////////////////////////////////////////////////////// ////////////////////////////////////////////////////// ////////////////////////////////////////////////////// ////////////////////////////////////////////////////// ////////////////////////////////////////////////////// ////////////////////////////////////////////////////// ////////////////////////////////////////////////////// ////////////////////////////////////////////////////// ////////////////////////////////////////////////////// ////////////////////////////////////////////////////// ////////////////////////////////////////////////////// ////////////////////////////////////////////////////// ©2015 Bonnie Rose Hudson WriteBonnieRose.com Cologne/is/in/a/region/of/Germany/called/the/ Rhineland./Its/biggest/and/most/famous//////// building/is/the/Cologne/Cathedral,/a/giant///// church/that/stretches/515/feet/high!/Inside///// the/church/you/can/find/many/beautiful//////// pieces/of/art,/some/more/than/500/years/old./ Cologne/is/in/a/region/of/Germany/called/the/ Rhineland./Its/biggest/and/most/famous//////// building/is/the/Cologne/Cathedral,/a/giant///// church/that/stretches/515/feet/high!/Inside///// the/church/you/can/find/many/beautiful//////// -

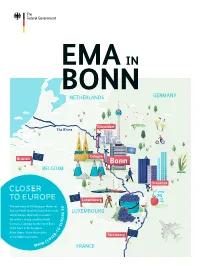

Closer to Europe — Tremendous Opportunities Close By: Germany Is Applying Interview – a Conversation with Bfarm Executive Director Prof

CLOSER TO EUROPE The new home of the European Medicines U E Agency (EMA) should be located centrally . E within Europe. Optimally accessible. P Set within a strong neigh bourhood. O R Germany is applying for the city of Bonn, U E at the heart of the European - O T Rhine Region, to be the location - R E of the EMA’s new home. S LO .C › WWW FOREWORD e — Federal Min öh iste Gr r o nn f H a e rm al e th CLOSER H TO EUROPE The German application is for a very European location: he EU 27 will encounter policy challenges Healthcare Products Regulatory Agency. The Institute Bonn. A city in the heart of Europe. Extremely close due to Brexit, in healthcare as in other ar- for Quality and Efficiency in Health Care located in T eas. A new site for the European Medicines nearby Cologne is Europe’s leading institution for ev- to Belgium, the Netherlands, France and Luxembourg. Agency (EMA) must be found. Within the idence-based drug evaluation. The Paul Ehrlich Insti- Situated within the tri-state nexus of North Rhine- EU, the organisation has become the primary centre for tute, which has 800 staff members and is located a mere drug safety – and therefore patient safety. hour and a half away from Bonn, contributes specific, Westphalia, Hesse and Rhineland-Palatinate. This is internationally acclaimed expertise on approvals and where the idea of a European Rhine Region has come to The EMA depends on close cooperation with nation- batch testing of biomedical pharmaceuticals and in re- life. -

Baubedingte Fahrplanänderungen S-Bahn-Verkehr S 1 Solingen

Baubedingte Fahrplanänderungen S-Bahn-Verkehr Herausgeber Kommunikation Infrastruktur der Deutschen Bahn AG Stand 06.05.2021 S 1 Solingen – Düsseldorf – Duisburg – Essen – Dortmund in der Nacht Montag/Dienstag, 31. Mai/1. Juni, 20.45 – 1.15 Uhr Schienenersatzverkehr Solingen Hbf UV Düsseldorf Hbf Ausfall der Halte Düsseldorf Volksgarten V Düsseldorf-Eller Mitte (Ersatz durch Taxis) Mehrere S-Bahnen dieser Linie werden zwischen Solingen Hbf und Düsseldorf Hbf durch Busse ersetzt. Beachten Sie die 49 Min. frühere Abfahrt bzw. spätere Ankunft der Busse in Solingen Hbf. In Düsseldorf Hbf haben Sie von den Bussen Anschluss an die planmäßigen S-Bahnen in Richtung Dortmund. Mehrere S-Bahnen in Richtung Solingen halten nicht in Düsseldorf Volksgarten, Düsseldorf-Oberbilk und Düsseldorf-Eller Mitte. Als Ersatz von/zu den ausfallenden Halten fahren Taxis zwischen Düsseldorf Hbf und Düsseldorf-Eller Mitte. Beachten Sie die bis zu 32 Min. früheren/späteren Fahrzeiten der Taxis. In Düsseldorf Hbf besteht Anschluss zwischen den S-Bahnen und den Taxis. Bitte beachten Sie, dass die Haltestellen des Schienenersatzverkehrs nicht immer direkt an den jeweiligen Bahnhöfen liegen. Die Fahrradmitnahme ist in den Bussen leider nur sehr eingeschränkt möglich. Grund Oberleitungsarbeiten zwischen Solingen Hbf und Düsseldorf Hbf Kontaktdaten https://bauinfos.deutschebahn.com/kontaktdaten/DBRegioNRW Diese Fahrplandaten werden ständig aktualisiert. Bitte informieren Sie sich kurz vor Ihrer Fahrt über zusätzliche Änderungen. Bestellen Sie sich unseren kostenlosen Newsletter und erhalten Sie alle baubedingten Fahrplanänderungen per E-Mail Xhttps://bauinfos.deutschebahn.com/newsletter Fakten und Hintergründe zu Bauprojekten in Ihrer Region finden Sie auf https://bauprojekte.deutschebahn.com Seite 1 S 1 Düsseldorf Hbf ◄► Solingen Hbf Halt- und Teilausfälle für Spätzüge 31.05.2021 (21:00) bis 01.06.2021 (5:00) Sehr geehrte Fahrgäste, aufgrund von Oberleitungsarbeiten zwischen Düsseldorf ◄► Solingen kommt es bei den abendlichen Fahrten der Linie S 1 zu Halt- oder Teilausfällen. -

Solingen – Wuppertal Reise DB Den in Sie Erhalten Antrag Den

www.mobil.nrw/mobigarantie unter unter zentren, VRR/Abellio-KundenCentern oder oder VRR/Abellio-KundenCentern zentren, Bonn – Köln – Solingen – Wuppertal - Reise DB den in Sie erhalten Antrag Den und Stadtverkehr Osnabrück). Stadtverkehr und Montag – Freitag 1) Sie unterwegs sind (außer PaderSprinter PaderSprinter (außer sind unterwegs Sie Fr Bonn-Mehlem ab 04:43 05:41 06:43 07:43 08:43 12:43 13:43 15:43 16:43 17:43 18:43 19:43 20:43 21:43 22:43 23:43 00:43 01:43 Nahverkehrsticket oder Verbund welchem Bonn-Bad Godesberg 04:46 05:44 06:46 07:46 08:46 12:46 13:46 15:46 16:46 17:46 18:46 19:46 20:46 21:46 22:46 23:46 00:46 01:46 egal, mit welchem Nahverkehrsmittel und und Nahverkehrsmittel welchem mit egal, Bonn UN Campus 04:49 05:47 06:50 07:50 08:50 12:50 13:50 15:50 16:50 17:49 18:50 19:49 20:50 21:50 22:50 23:50 00:50 01:50 – NRW-Tarif beim sowie Gemeinschaftstarifen Bonn Hbf an 04:52 05:50 06:52 07:52 08:52 12:52 13:52 15:52 16:52 17:52 18:52 19:52 20:52 21:52 22:52 23:52 00:52 01:52 allen nordrhein-westfälischen Verbund- und und Verbund- nordrhein-westfälischen allen Bonn Hbf ab 04:53 05:51 06:083) 06:53 07:093) 07:53 08:083) 08:53 12:53 13:08 13:53 15:08 15:53 16:08 16:53 17:08 17:53 18:08 18:53 19:08 19:53 20:10 20:53 21:53 22:53 23:53 00:53 01:53 Ziel nutzen. -

How to Get to Akademie Remscheid Address: Akademie Remscheid

How to get to Akademie Remscheid Address: Akademie Remscheid Küppelstein 34 42857 Remscheid Germany http://akademieremscheid.de By air If you travel by plane it would be best to fly to Dusseldorf International Airport (Düsseldorf Airport): http://www.dus.com/en (or optionally to Cologne Bonn Airport). In Dusseldorf airport take the sky train to the train station “Dusseldorf Airport”. Buy a ticket at the machine: VRR, Preisstufe C, 11,50 € Take the suburban train S 1 to “Solingen Hauptbahnhof” (Solingen main station) at track 6. The travel lasts 35 minutes. These trains depart every 20 minutes. In Solingen Hauptbahnhof change for the suburban train ABR S7 to “Remscheid- Güldenwerth” (station “Güldenwerth” in Remscheid), in the direction of “Wuppertal Hauptbahnhof” which takes 17 minutes, departure every 20 minutes from track 9. Let us know at what time you arrive at “Remscheid-Güldenwerth”. We will pick you up. By train Take the train to “Solingen Hauptbahnhof” (Solingen main station) or “Wuppertal Hauptbahnhof” (Wuppertal main station). There you must change and take the suburban train ABR S7 to “Remscheid-Güldenwerth” (station “Güldenwerth” in Remscheid), in the direction of “Wuppertal Hauptbahnhof” or “Solingen Hauptbahnhof”. From Wuppertal Hauptbahnhof it takes 35 minutes and from Solingen Hauptbahnhof it takes 17 minutes. Let us know at what time you arrive at “Remscheid-Güldenwerth”. We will pick you up. http://www.bahn.com/i/view/index.shtml By car By car from the motorway A1 Dortmund-Cologne (coming from Dortmund): Exit Remscheid / Solingen (not: Remscheid-Lennep), from there to the right about 10 km on the B 229 through Remscheid, always direction Reinshagen and follow signs to the Academy. -

US&FCS Germany

PUBLIC RELEASE INTERNATIONAL TRADE ADMINISTRATION US&FCS Germany: While Generally Productive, Its Priorities, Resources, and Activities Require Reassessment Inspection Report No. IPE-9287 / July 1997 Office of Inspections and Program Evaluations U.S. Department of Commerce Final Report IPE-9287 Office of Inspector General July 1997 TABLE OF CONTENTS PAGE EXECUTIVE SUMMARY ................................................... i INTRODUCTION ..........................................................1 PURPOSE AND SCOPE .....................................................1 BACKGROUND ...........................................................3 OBSERVATIONS AND CONCLUSIONS .......................................7 I. PROGRAM ACTIVITIES ........................................7 A. Some Market Research Being Driven by Numbers Instead of Need .....7 B. Country Commercial Guide Needs to Better Reflect Marketing Characteristics of Eastern Germany .............................9 C. Showcase Europe Impact Questionable and Should Be More Precisely Measured ........................................10 D Increased Travel and Tourism Effort Required ...................11 E. Performance Measurements Needed ...........................12 F. Trade Fair and International Buyer Program Participation Need Reassessment ............................................14 G. Technical Support and Training Inadequate ......................15 H. BXA Guidance Is Not Being Followed .........................17 II. STAFFING ...................................................19 -

Ausgezeichnete Praxisbeispiele

Ausgezeichnete Praxisbeispiele Klimaaktive Kommune 2018 Ein Wettbewerb des Bundesumweltministeriums und des Deutschen Instituts für Urbanistik Impressum Ausgezeichnete Praxisbeispiele: Klimaaktive Kommune 2018 – Ein Wettbewerb des Bundesministeriums für Umwelt, Naturschutz, und nukleare Sicherheit und des Deutschen Instituts für Urbanistik (Difu) Diese Veröffentlichung wird kostenlos abgegeben und ist nicht für den Verkauf bestimmt. Das Wettbewerbsteam des Difu: Cornelia Rösler (Projektleitung), Manja Estermann, Anna Hogrewe-Fuchs, Anna-Kristin Jolk, Marco Peters, Maja Röse, Anne Roth, Ulrike Vorwerk, Björn Weber Konzept: Anna Hogrewe-Fuchs Redaktion: Anna Hogrewe-Fuchs, Sigrid Künzel Textbeiträge: Martin Dirauf, Manja Estermann, Marc Daniel Heintz, Nico Hickel, Anna Hogrewe-Fuchs, Maren Kehlbeck, Thomas Königstein, Jens-Peter Koopmann, Tycho Kopperschmidt, Professor Carsten Kühl, Landeshauptstadt Magdeburg, Gabriele Mallasch, Anne Roth, Marco Peters, Svenja Schulze, Björn Weber, Sabine Wirtz Gestaltung: 6grad51 – Büro für visuelle Kommunikation Alle Rechte vorbehalten. Gefördert durch: Bundesministerium für Umwelt, Naturschutz, und nukleare Sicherheit aufgrund eines Beschlusses des Deutschen Bundestages. Herausgeber: Deutsches Institut für Urbanistik gGmbH (Difu), Auf dem Hunnenrücken 3, 50668 Köln Köln 2019 Inhalt 4 Vorwort Bundesumweltministerium Svenja Schulze 5 Vorwort Difu Prof. Dr. Carsten Kühl 6 Der Wettbewerb „Klimaaktive Kommune 2018“ 14 Die Preisträger der Kategorie 1: Ressourcen- und Energieeffizienz in der Kommune 16 Landeshauptstadt -

Doing Business in Germany

DOING BUSINESS IN GERMANY CONTENTS 1 – Introduction 3 2 – Business Environment 4 3 – Foreign Investment 9 4 – Setting up a Business 11 5 – Employment 16 6 – Taxation 21 7 – Accounting & Reporting 32 8 – UHY Representation in Germany 35 DOING BUSINESS IN GERMANY 3 1 – INTRODUCTION UHY is an international organisation providing accountancy, tax business management and consultancy services through financial business centres in around 90 countries throughout the world. Through this network business partners work together. So not only specialist knowledge and experience within the own border can be offered. But, they are also able to conduct transnational operations for clients. This detailed report provides key issues and information for investors considering business operations in Germany. It has been provided by the offices of UHY representatives. A detailed firm profile of UHY’s representation in Germany can be found in section 8. You are more than welcome to contact single firms for any inquiries you may have. Information in the following pages is periodically updated. Anyway, inevitably the information given is general and subjected to change and should be used for guidance only. For specific matters, you are strongly advised to obtain further information. Additionally, you should seek for professional advice before making any decisions. This publication is current as of March 2019. We look forward helping you doing business in Germany. DOING BUSINESS IN GERMANY 4 2 – BUSINESS ENVIRONMENT GEOGRAPHY AND CLIMATE Germany is located in the centre of Europe and is one of the largest European countries. Neighbouring countries are Poland, the Czech Republic, Austria, Switzerland, France, Luxembourg, Belgium, the Netherlands and Denmark. -

Solingen Hbf

RB48 RB RB48 Rhein-Wupper - Bahn DB-Kursbuchstrecke: 455, 470 und zurück Wuppertal Hbf - W-Barmen W-Oberbarmen Bonn - Köln Solingen Hbf BonnBonn MehlemKöln Hbf K-Messe/DeutzHbf K-MülheimLeverkusenOpladenLeichlingen Schlebusch Solingen Hbf Haan Gruiten W-Vohwinkel Wuppertal Hbf und zurück P+R P+R P+R Fahrradmitnahme begrenzt möglich Anschlüsse siehe Haltestellenverzeichnis/Linienplan RB48 RB RB RB48 montags bis freitags RB48 Haltestellen Abfahrtszeiten Bonn Mehlem Bf ab 5.43 6.43 7.43 8.43 10.43 11.43 12.43 Wuppertal Hbf - W-Barmen W-Oberbarmen Bonn - Köln Solingen Hbf Bonn-Bad Godesberg 46 46 46 46 46 46 46 Bonn Hauptbahnhof an 5.52 6.52 7.52 8.52 10.52 11.52 12.52 Bonn Hauptbahnhof ab 5.53 6.08 6.53 7.08 7.53 8.08 8.53 10.53 11.53 12.53 Roisdorf 58 13 58 13 58 13 58 58 58 58 Sechtem 6.02 18 7.02 18 8.02 18 9.02 11.02 12.02 13.02 Brühl 06 22 06 22 06 22 06 06 06 06 Kalscheuren Bf 11 29 11 30 10 30 10 10 10 10 Köln Süd 15 40 15 40 15 42 15 15 15 15 Köln West 18 43 18 43 18 44 18 18 18 18 Köln Hbf an 6.22 6.47 7.22 7.47 8.22 8.49 9.22 11.22 12.22 13.22 Köln Hbf ab 0.52 5.25 5.52 6.25 6.52 7.25 7.52 8.25 8.52 9.25 9.52 usw. -

German Immersion

Study Abroad German Immersion Willy Piñón heads to Europe to see what Germany has to offer to the German learner In the heart of Europe, Germany has the world’s third Marx-Haus, built in 1924. The city is home to several museums, and largest economy. Since the fall of the Berlin wall in 1989, and the the library holds a collection of works by the poet Heinrich Heine. reunification process which formally concluded in 1990, Germany has Berlin, located in the northeast, is the nation’s capital, as well as its undergone massive efforts, both governmental and individual, to largest city. It is home to world-renowned universities, and boasts restore the sense of unity that the manly created barrier had broken architectural sights of great cultural and historical significance. If you since the wall was built in 1961. Germany is politically divided into 16 are a sports fan, a tour of Berlin’s Olympiastadion, home to the final federal states, each of which is a world of adventure in itself. match of the 2006 soccer World Cup, and the 1936 Olympic Games, The state of Bavaria, located in the south east corner of the coun- is a must. try, is famous for its beautiful forests, lakes, and the best beer in the In the northwest of Germany, lies Hamburg, home of the ninth world. The state capital is the lively and fashionable city of Munich, largest harbor in the world. Emperor Charlemagne, in the year 808 AD, which is a young, liberal city ideal for students. Bavaria is also the ordered the construction of the Hamburg Castle, from which the city birthplace of Pope Benedict XVI, and home of the famous Oktoberfest, later took its name.