The Edelweiss Pirates: an Exploratory Study Ryan Reilly

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

A Youth in Upheaval! Christine E

Southern Illinois University Carbondale OpenSIUC Honors Theses University Honors Program 5-2006 A Youth in Upheaval! Christine E. Nagel Follow this and additional works at: http://opensiuc.lib.siu.edu/uhp_theses Recommended Citation Nagel, Christine E., "A Youth in Upheaval!" (2006). Honors Theses. Paper 330. This Dissertation/Thesis is brought to you for free and open access by the University Honors Program at OpenSIUC. It has been accepted for inclusion in Honors Theses by an authorized administrator of OpenSIUC. For more information, please contact [email protected]. A Youth in Upheaval! Christine E. Nagel University Honors Thesis Dr. Thomas F. Thibeault May 10,2006 A Youth in Upheaval Introduction The trouble started for the undesirables when the public systems started being filtered. Jewish and other non Aryan businesses were being boycotted. The German people (not including Jews and other non Aryans) were forbidden to use these businesses. They could not shop in their grocery stores. Germans could not bring their finances to their banks. It eventually seemed best not to even loiter around these establishments of business. Not stopping there, soon Jewish people could no longer hold occupations at German establishments. Little by little, the Jewish citizens started losing their rights, some even the right to citizenship. They were forced to identifY themselves in every possible way, wherever they went, so that they were detectable among the Germans. The Jews were rapidly becoming cornered. These restrictions and tragedies did not only affect the adults. Children were affected as well, if not more. Soon, they were not allowed to go to the movies, own bicycles, even be out in public without limitations. -

Nationalsozialistische Schulverwaltung in Hamburg. Vier Führungspersonen

H H H F HF Hamburger Historische Forschungen | Band 1 Hamburger Historische Forschungen | Band 12 Uwe Schmidt Nationalsozialistische Schul- verwaltung in Hamburg Nach dem Machtwechsel in Hamburg Neben Karl Witt waren dies die Prote- wurde am 8. März 1933 die Schulver- gés des Gauleiters und Reichsstatthal- Vier Führungspersonen waltung dem Deutschnationalen und ters Karl Kaufmann Wilhelm Schulz, späteren Nationalsozialisten Karl Witt Albert Henze und Ernst Schrewe. Ihre unterstellt. Umgestellt auf das natio- Nähe zum Machtzentrum um Kauf- nalsozialistische Führungsprinzip wur- mann führte zu sehr unterschiedlichen de sie in zunehmendem Maße für die formalen wie informellen Verankerun- Durchsetzung nationalsozialistischer gen in den Mechanismen des poly- Erziehungsvorstellungen instrumen- kratischen nationalsozialistischen talisiert. Diese wurden vor allem über Systems. Der politische Druck, der von die Personen durchgesetzt, welche die der Spitze der Schulverwaltung auf die Behörde leiteten oder aber durch in- Schulen ausgeübt wurde, verstärkte formell ausgeübte Macht dominierten. sich seit Kriegsbeginn und erreichte sei- Verdeutlicht wird daher die Position nen Höhepunkt in der Machtfülle und der vier schulbezogenen Funktionsträ- rücksichtslosen Machtausübung des ger im Macht- und Herrschaftssystem nationalsozialistischen Senatsdirektors des Hamburger Nationalsozialismus. und Gauschulungsleiters Albert Henze. Nationalsozialistische Schulverwaltung in Hamburg ISBN 978-3-937816-49-4 ISSN 1865-3294 2 Hamburg University Press Nationalsozialistische -

Programm Jan–Mär 2016 1 NS-Dokumentationszentrum München – Lernen Und Erinnern Am Historischen Ort Programm 1/2016

Programm Jan–Mär 2016 1 NS-Dokumentationszentrum München – Lernen und Erinnern am historischen Ort Programm 1/2016 Im neuen Jahr setzt das im Mai 2015 eröffnete NS-Dokumentationszentrum München sein Veranstaltungsprogramm mit Filmen, Konzerten, Lesungen, Diskussionsrunden und einem Zeitzeugengespräch fort. Im Rahmenprogramm zu unserer aktuellen Sonderausstellung „Der Warschauer Aufstand 1944“, die noch bis Ende Februar zu sehen sein wird, veranstalten wir in Zusammenarbeit mit unseren Partnern aus Polen einen Vortrag und drei Podiumsdiskussionen mit Experten aus beiden Ländern. Die Verbrechen und der Terror im besetzen Polen, dessen Kultur und Staat zerstört werden sollten, sind bis heute in Deutschland zu wenig bekannt. Am Tag des Gedenkens an die Opfer des Nationalsozialismus widmen wir uns der Verfolgung der Zeugen Jehovas. Weitere Themen sind u.a. Jugend- kultur und Opposition, Wirtschaft und Konsum sowie Verfolgung und Terror in der NS-Zeit. Außerdem setzen wir die Konzertreihe „Feindsender – Jazz im zeitlichen Umfeld der Nazi-Diktatur“ fort. Die Auseinandersetzung mit dem Nationalsozialismus, in dem Recht und Freiheit mit Füßen getreten wurden, kann helfen, besser zu erkennen, was das Wesen der Demokratie ausmacht und wie wir für deren Schutz ein- treten können. Freiheit ist immer die Freiheit der anders Denkenden, Glaubenden, Lebenden und Aussehenden. Dies steht jeden Tag aufs Neue auf dem Prüfstand. Prof. Dr.-Ing. Winfried Nerdinger Gründungsdirektor Foto: Orla Connolly/NS-Dokumentationszentrum Programmübersicht 1.1.– 31.3.2016 -

Germany - Solingen

Germany - Solingen The city of Solingen (population 165,000), situated on the river Wupper 30 km northeast of Cologne, was founded in 1374 and has grown famous as a blade manufacturing centre; becoming Sheffield's main competitor in the cutlery industry. The history of German sword making can be traced back to 1250. Solingen became established as a metalworking centre, not only because of the presence of iron ore and a plentiful supply of timber for charcoal and water to drive the grindstones but because the nearby town of Cologne was Germany's richest trading centre. Solingen was making fine quality sword blades in the fourteenth century and was contracted to sell all its swords and edged weapons to Cologne where handles were attached and the finished weapons sold. The grinders and temperers' guild was formed in 1401 and the sword smiths' guild in 1472. The cutlers' guild, with 82 cutlers, was mentioned for the first time in 1571 and the scissor smiths formed their guild in 1794. The first cutlery to be marked with the makers name (on the handle) - 1627 Hand forging was a skilled and time consuming process but fast striking mechanical hammers, driven by water wheels, were used in the 16th century to speed up the process of hand forging by around fivefold. Factories housing mechanical hammers were built on the rivers in and around Solingen to roughly forge sword blades before they were finished by hand forging. Although fear of unemployment caused the sword forging guild to argue that hand forged steel was better. Sheffield was still hand forging steel at this time but was using water to drive grinding wheels. -

This Cannot Happen Here Studies of the Niod Institute for War, Holocaust and Genocide Studies

This Cannot Happen Here studies of the niod institute for war, holocaust and genocide studies This niod series covers peer reviewed studies on war, holocaust and genocide in twentieth century societies, covering a broad range of historical approaches including social, economic, political, diplomatic, intellectual and cultural, and focusing on war, mass violence, anti- Semitism, fascism, colonialism, racism, transitional regimes and the legacy and memory of war and crises. board of editors: Madelon de Keizer Conny Kristel Peter Romijn i Ralf Futselaar — Lard, Lice and Longevity. The standard of living in occupied Denmark and the Netherlands 1940-1945 isbn 978 90 5260 253 0 2 Martijn Eickhoff (translated by Peter Mason) — In the Name of Science? P.J.W. Debye and his career in Nazi Germany isbn 978 90 5260 327 8 3 Johan den Hertog & Samuël Kruizinga (eds.) — Caught in the Middle. Neutrals, neutrality, and the First World War isbn 978 90 5260 370 4 4 Jolande Withuis, Annet Mooij (eds.) — The Politics of War Trauma. The aftermath of World War ii in eleven European countries isbn 978 90 5260 371 1 5 Peter Romijn, Giles Scott-Smith, Joes Segal (eds.) — Divided Dreamworlds? The Cultural Cold War in East and West isbn 978 90 8964 436 7 6 Ben Braber — This Cannot Happen Here. Integration and Jewish Resistance in the Netherlands, 1940-1945 isbn 978 90 8964 483 8 This Cannot Happen Here Integration and Jewish Resistance in the Netherlands, 1940-1945 Ben Braber Amsterdam University Press 2013 This book is published in print and online through the online oapen library (www.oapen.org) oapen (Open Access Publishing in European Networks) is a collaborative initiative to develop and implement a sustainable Open Access publication model for academic books in the Humanities and Social Sciences. -

Applying What We Have Learned

Appendix APPLYING WHAT WE HAVE LEARNED Always hold firmly to the thought that each one of us can do some- thing to bring some portion of misery to an end. —Syracuse Cultural Workers1 Shortly after the September 11, 2001, tragedy, one of the authors of this book heard a moral tale about a child who came to her grandfather indig- nant over an injustice she had experienced. “What shall I do, grandfa- ther?” she asked. Her grandfather replied, “I have two wolves inside me. One gets very angry when I have been treated unfairly and it wants to hit back, to hurt the one who hurt me. The other wolf also gets angry when I have been unfairly treated, but it wants justice and peace more than any- thing, and it wants to heal the rift between me and my aggressor.” “Which wolf wins, grandfather?” the little girl asked. “The one I feed,” he replied. If by reading this book you have been inspired by the stories of the courageous individuals and groups, but you have wondered if you could ever have that kind of courage, you are not alone. We wonder also. We cannot help but be appalled at the perpetrators of evil we have read about in this book, nor can we help admiring the courageous resistors about whom we have learned. But it is easy to separate ourselves from both groups. We may say to ourselves, “Surely I would never kill children as did the Nazis, or force pregnant women to take dangerous drugs just to 166 COURAGEOUS RESISTANCE boost my overtime pay,” as some U.S. -

Baubedingte Fahrplanänderungen S-Bahn-Verkehr S 1 Solingen

Baubedingte Fahrplanänderungen S-Bahn-Verkehr Herausgeber Kommunikation Infrastruktur der Deutschen Bahn AG Stand 06.05.2021 S 1 Solingen – Düsseldorf – Duisburg – Essen – Dortmund in der Nacht Montag/Dienstag, 31. Mai/1. Juni, 20.45 – 1.15 Uhr Schienenersatzverkehr Solingen Hbf UV Düsseldorf Hbf Ausfall der Halte Düsseldorf Volksgarten V Düsseldorf-Eller Mitte (Ersatz durch Taxis) Mehrere S-Bahnen dieser Linie werden zwischen Solingen Hbf und Düsseldorf Hbf durch Busse ersetzt. Beachten Sie die 49 Min. frühere Abfahrt bzw. spätere Ankunft der Busse in Solingen Hbf. In Düsseldorf Hbf haben Sie von den Bussen Anschluss an die planmäßigen S-Bahnen in Richtung Dortmund. Mehrere S-Bahnen in Richtung Solingen halten nicht in Düsseldorf Volksgarten, Düsseldorf-Oberbilk und Düsseldorf-Eller Mitte. Als Ersatz von/zu den ausfallenden Halten fahren Taxis zwischen Düsseldorf Hbf und Düsseldorf-Eller Mitte. Beachten Sie die bis zu 32 Min. früheren/späteren Fahrzeiten der Taxis. In Düsseldorf Hbf besteht Anschluss zwischen den S-Bahnen und den Taxis. Bitte beachten Sie, dass die Haltestellen des Schienenersatzverkehrs nicht immer direkt an den jeweiligen Bahnhöfen liegen. Die Fahrradmitnahme ist in den Bussen leider nur sehr eingeschränkt möglich. Grund Oberleitungsarbeiten zwischen Solingen Hbf und Düsseldorf Hbf Kontaktdaten https://bauinfos.deutschebahn.com/kontaktdaten/DBRegioNRW Diese Fahrplandaten werden ständig aktualisiert. Bitte informieren Sie sich kurz vor Ihrer Fahrt über zusätzliche Änderungen. Bestellen Sie sich unseren kostenlosen Newsletter und erhalten Sie alle baubedingten Fahrplanänderungen per E-Mail Xhttps://bauinfos.deutschebahn.com/newsletter Fakten und Hintergründe zu Bauprojekten in Ihrer Region finden Sie auf https://bauprojekte.deutschebahn.com Seite 1 S 1 Düsseldorf Hbf ◄► Solingen Hbf Halt- und Teilausfälle für Spätzüge 31.05.2021 (21:00) bis 01.06.2021 (5:00) Sehr geehrte Fahrgäste, aufgrund von Oberleitungsarbeiten zwischen Düsseldorf ◄► Solingen kommt es bei den abendlichen Fahrten der Linie S 1 zu Halt- oder Teilausfällen. -

Everyday Antisemitism in Pre-War Nazi Germany: the Popular Bases by Michael H

Everyday Antisemitism in Pre-War Nazi Germany: The Popular Bases By Michael H. Kater The thesis that manifestations of "Antisemitism" in the Third Reich were largely a result of manipulations by Nazi politicians rather than the reflection of true sentiments among the German people appears firmly established nowadays. This thesis treats the course of German history as being devoid of a specific antisemitic tradition and regards what authentic symptoms of Antisemitism there were, before and during Hitler's rise to power, as merely incidental.1 One might well agree with Hajo Holborn's suggestion that Hitler, the supreme propagandist of his Nazi Party (NSDAP) and of the Third Reich, conjured up Antisemitism by arousing hatred within the Germans, in order to further the regime's ultimate goals. But then one cannot, like Eva Reichmann, altogether discount pre-existing notions of Judeo-phobia among the German people and, by implication, absolve them of their complicity in the Holocaust.2 Since the appearance of Reichmann's and Holborn's writings, 1 The first view has been succinctly stated by Thomas Nipperdey, “1933 und Kontinuitaet der deutschen Geschichte,” Historische Zeitschrift 227, 1978: 98. An example of the second view is in William Sheridan Allen, The Nazi Seizure of Power: The Experience of a Single German Town 1930–1935 , Chicago, 1965, p. 77, who writes that the inhabitants of the small North German town of Northeim (“Thalburg”) were drawn to anti-Semitism because they were drawn to Nazism, not the other way around ' . 2 Hajo Holborn, “Origins and Political Character of Nazi Ideology,” Political Science Quarterly 79, 1964: 546; Eva G. -

Cologne Cathedral

Arnold Wol Cologne Cathedral Its History – Its Artworks Edited and extended by Barbara Schock-Werner About this Cathedral Guide Arnold Wol, who was ‘Dombaumeister’ (cathedral architect) at Cologne Cathedral between 1972 and 1998, created this guide in collaboration with Greven Verlag, Cologne. His wealth of knowledge on the history of the cathedral and his profound knowledge of the interior have both gone into this book, and there are no other publications that do justice to both of these aspects in equal measure. is book presents the reader with the full spectrum and signicance of the architectural and artistic creations that Cologne Cathedral has on oer. In addition, the fold-out oor plan is a useful orientation aid that allows cathedral visitors to search for informa- tion on individual objects. Six editions of this book have now been published. Arnold Wol has overseen all of them. For this new edition he has tasked me with bringing the text up to date in line with the latest research and introducing the new- ly added artworks. e publisher has taken this opportunity to implement a new layout as well. Nevertheless, for me this guide remains rmly linked with the name of the great ‘Dombaumeister’ Arnold Wol. Barbara Schock-Werner Former Dombaumeister (1999–2012) Hint for using this guide: in the text that follows, the architectural features are labelled with capital letters, the furnishings, fittings, artworks, and other interesting objects with numbers. The letters and numbers correspond to those on the fold-out floor plan at the back. The tour starts on page 10. -

Teacher's Guide

TEACHER’S GUIDE Growing Up in Nazi Germany: Teaching Friedrich by Hans Peter Richter GROWING UP IN NAZI GERMANY: Teaching Friedrich by Hans Peter Richter Table of Contents INTRODUCTION PAGE 1 LESSON PLANS FOR INDIVIDUAL CHAPTERS Setting the Scene (1925) PAGE 3 In the Swimming Pool (1938) PAGE 42 Potato Pancakes (1929) PAGE 4 The Festival (1938) PAGE 44 Snow (1929) PAGE 6 The Encounter (1938) PAGE 46 Grandfather (1930) PAGE 8 The Pogrom (1938) PAGE 48 Friday Evening (1930) PAGE 10 The Death (1938) PAGE 52 School Begins (1931) PAGE 12 Lamps (1939) PAGE 53 The Way to School (1933) PAGE 14 The Movie (1940) PAGE 54 The Jungvolk (1933) PAGE 16 Benches (1940) PAGE 56 The Ball (1933) PAGE 22 The Rabbi (1941) PAGE 58 Conversation on the Stairs (1933) PAGE 24 Stars (1941) PAGE 59 Herr Schneider (1933) PAGE 26 A Visit (1941) PAGE 61 The Hearing (1933) PAGE 28 Vultures (1941) PAGE 62 In the Department Store (1933) PAGE 30 The Picture (1942) PAGE 64 The Teacher (1934) PAGE 32 In the Shelter (1942) PAGE 65 The Cleaning Lady (1935) PAGE 35 The End (1942) PAGE 67 Reasons (1936) PAGE 38 RESOURCE MATERIALS PAGE 68 This curriculum is made possible by a generous grant from the Conference on Jewish Material Claims Against Germany: The Rabbi Israel Miller Fund for Shoah Research, Documentation and Education. Additional funding has been provided by the Estate of Else Adler. The Museum would also like to thank the Board of Jewish Education of Greater New York for their input in the project, and Ilana Abramovitch, Ph.D. -

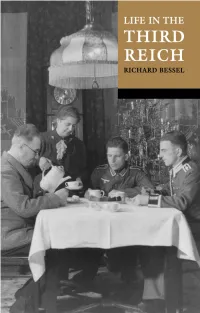

Life in the Third Reich

LIFE IN THE THIRD REICH Richard Bessel is Professor of Twentieth-Century History at the University of York. His other publica- tions include Political Violence and the Rise of Nazism, Germany after the First World War, and (ed.) Fascist Italy and Nazi Germany: Comparisons and Contrasts. The Contributors Richard Bessel Ian Kershaw William Carr Jeremy Noakes Michael Geyer Detlev Peukert Ulrich Herbert Gerhard Wilke This page intentionally left blank LIFE IN THE THIRD REICH Edited, with an Introduction, by RICHARD BESSEL OXPORD UNIVERSITY PRESS OXPORD UNIVERSITY PKBSS Great Clarendon Street, Oxford 0x2 6op Oxford University Press is a department of the University of Oxford. It furthers the University's objective of excellence in research, scholarship, and education by publishing worldwide in Oxford New York Athens Auckland Bangkok Bogoti Buenos Aires Cape Town Chennai Dar es Salaam Delhi Florence Hong Kong Istanbul Karachi Kolkata Kuala Lumpur Madrid Melbourne Mexico City Mumbai Nairobi Paris Sao Paulo Shanghai Singapore Taipei Tokyo Toronto Warsaw with associated companies in Berlin Ibadan Oxford is a registered trade mark of Oxford University Press in the UK and in certain other countries Introduction and Suggestions for Further Reading © Richard Bessel 1987, 2001 'Political Violence and the Nazi Seizure of Power'. 'Vfflage Life in Nazi German/. 'Youth in the Third Reich', 'Hitler and the Germans', 'Nazi Policy against the Jews', and 'Social Outcasts in the Third Reich' © History Today 1985 "The Nazi State Reconsidered' and 'Good Times, Bad Times; Memories of the Third Reich' © History Today 1986 These articles werejirst published in History Today between October 1985 and February 1986 First issued, with a new introduction, as an Oxford University Press paperback, and simultaneously in a hardback edition, 1987 Reissued in 2001 All rights reserved. -

Solingen – Wuppertal Reise DB Den in Sie Erhalten Antrag Den

www.mobil.nrw/mobigarantie unter unter zentren, VRR/Abellio-KundenCentern oder oder VRR/Abellio-KundenCentern zentren, Bonn – Köln – Solingen – Wuppertal - Reise DB den in Sie erhalten Antrag Den und Stadtverkehr Osnabrück). Stadtverkehr und Montag – Freitag 1) Sie unterwegs sind (außer PaderSprinter PaderSprinter (außer sind unterwegs Sie Fr Bonn-Mehlem ab 04:43 05:41 06:43 07:43 08:43 12:43 13:43 15:43 16:43 17:43 18:43 19:43 20:43 21:43 22:43 23:43 00:43 01:43 Nahverkehrsticket oder Verbund welchem Bonn-Bad Godesberg 04:46 05:44 06:46 07:46 08:46 12:46 13:46 15:46 16:46 17:46 18:46 19:46 20:46 21:46 22:46 23:46 00:46 01:46 egal, mit welchem Nahverkehrsmittel und und Nahverkehrsmittel welchem mit egal, Bonn UN Campus 04:49 05:47 06:50 07:50 08:50 12:50 13:50 15:50 16:50 17:49 18:50 19:49 20:50 21:50 22:50 23:50 00:50 01:50 – NRW-Tarif beim sowie Gemeinschaftstarifen Bonn Hbf an 04:52 05:50 06:52 07:52 08:52 12:52 13:52 15:52 16:52 17:52 18:52 19:52 20:52 21:52 22:52 23:52 00:52 01:52 allen nordrhein-westfälischen Verbund- und und Verbund- nordrhein-westfälischen allen Bonn Hbf ab 04:53 05:51 06:083) 06:53 07:093) 07:53 08:083) 08:53 12:53 13:08 13:53 15:08 15:53 16:08 16:53 17:08 17:53 18:08 18:53 19:08 19:53 20:10 20:53 21:53 22:53 23:53 00:53 01:53 Ziel nutzen.