Download Download

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

How to Find Us

how to find us A24 Arriving by car from the north (Hamburg): · Take the A24 towards Berlin · At the interchange, “Dreieck Havelland” take the A10 towards “Berlin Zentrum.” A10 A111 · At the interchange “Dreieck Oranienburg” switch to the A111. A114 Again, follow the signs for “Berlin Zentrum” · From the A111 switch to A100 direction Leipzig A10 A100 Berlin · From the A100 take the Kaiserdamm exit (Exit No. 7), turning right onto Knobelsdorffstraße, then right onto B2 Sophie-Charlotten-Straße, and left onto Kaiserdamm A100 · At the Victory Tower roundabout (Siegessäule) take the first exit onto Hofjägerallee A115 · Turn left onto Tiergartenstraße Potsdam A113 · Turn right onto Ben-Gurion-Straße (B1/B96) · Turn left onto Potsdamer Platz A12 Arriving from the west (Hannover/Magdeburg)/ A2 Hannover A10 A13 from south (Munich/Leipzig): · Take the A9/A2 towards Berlin · At the “Dreieck Werder” interchange take the A10 towards “Berlin Zentrum” · At the “Dreieck Nuthetal” interchange take the A115, again following Stra Hauptbahnhof Alexanderplatz signs for “Berlin Zentrum” ß entunnel · Watch for signs and switch to the A100 heading towards Hamburg Tiergarten · From the A100 take the Kaiserdamm exit. e ß Follow directions as described above. ße B.-Gurion-Str. Bellevuestra Arriving from the south (Dresden): Leipziger Tiergartenstra ße Ebert Stra Platz · Take the A13 as far as the Schönefelder interchange Sony Center Potsdamer Leipziger Str. · At the Schönefelder interchange take the A113 Platz ße Ludwig-Beck-Str. U · At the interchange “Dreieck Neukölln” take the A100 Stra S er Voxstra am ß · Follow the A100 to Innsbrucker Platz sd e t Eichhorn- o Fontane P P · Turn right onto the Hauptstraße Platz Stresemannstra Alte Potsdamer Str. -

Dear Parents, I Am Writing to Provide You with Additional Information

Dear Parents, I am writing to provide you with additional information about the upcoming Grade 9 trip to Germany. If you would like more information, please do not hesitate to contact me. The trip will be chaperoned by Mr. Andrews, Mr. Dulcinio, Ms. Silva and Ms. Donovan. Should you need to get in contact with the chaperones during the trip, please call 925 609 962. Your child should be at the airport on Monday, May 5th before 07h00. The chaperones will collect your child in front of the flight board in the Departures section of Terminal 1. The return flight is scheduled to land at 17h30 on Friday, May 9th. The specific itinerary, including flight numbers and hotels, follows below. Sincerely, Nate Chapman Secondary School Principal May 5th – Lisbon/Munich Passengers must be at the airport at 07h00 for check in formalities. 09h15 - Departure from Lisbon to Munich – TAP flight TP 558 13h20 – Arrival at Munich Airport and transfer to the A & O München Hackerbrücke 16h30 - Third Reich Walking Tour (divide into two separate tour groups). Accommodation at A & O München Hackerbrücke for 2 nights. May 6th – Munich / Dachau / Neuschwanstein Castle / Munich Breakfast at hotel. Excursion Guided tours of Dachau + Neuschwanstein Accommodation at A & O München Hackerbrücke May 7th - Munich / Berlin Breakfast at hotel. 07h00 - Depart hotel 15h30 – Visit to Haus der Wannsee-Konferenz (outskirts of Berlin) 18h30 – Arrive and check in at Smart Stay Berlin City Hotel May 8th – Berlin Breakfast at hotel. 13.30-14.30 Topography of Terror (divide into 3 separate tour groups) 17.45 Dome of Reichstag Building (divide into two separate groups, names already submitted) Martin-Gropius-Bau Berlin Museum (next door to Topography of Terror) 20 Art students will view Accommodation at Smart Stay Berlin City Hotel May 9th – Berlin / Lisbon Breakfast at hotel. -

World War II: Germany

World War II: Germany Germany was the focus of World War II, which lasted from 1939 to 1945, and the reasons for this focus were diverse. Germany's nationalist aggression under the Nazi government stoked fires of distrust against Soviet Communism. The nations of Europe were drawn into the war one by one until the war spread across the continent. During the war, many actions (such as the Holocaust) of Nazi Germany were immoral and illegal. Historians often study Germany's government during the time of the war because it was a valid, legitimate government and not merely a revolutionary group. The Nazi government forced Germany into a totalitarian state (a government that controls all aspects of public and private life) that engaged most of the world's countries in war, and it is significant to examine the political structure of Germany. After the First World War, Germany struggled through a series of revolutions and finally, in 1918, formed the Weimar Republic. The Weimar Republic was Germany's attempt to establish a democratic government. The Weimar Constitution was written as the law of the land and it explained the nature of the new government. One of its key parts was the creation of a parliament. This parliament was called the Reichstag and the people of Germany voted for their representatives in the parliament. In 1925, President Paul Hindenburg was elected. He did not want to be president, but he supported the Constitution and appointed a group of advisors to help him. Unfortunately, these advisors did not all favor the Constitution as their president did. -

Ausbaugebiet Seite 1 Der Landkreis Oder-Spree

Breitbandausbau im Landkreis Oder-Spree Markterkundungsverfahren Anlage 1: Ausbaugebiet Der Landkreis Oder-Spree ist ein Flächenlandkreis mit einer Gesamtgröße von 2.256,75 km². Er besteht aus sechs Ämtern, sechs kreisangehörigen Städten und sechs amtsfreien Gemeinden. Gemäß den Angaben des Amtes für Statistik Berlin-Brandenburg hatte der Landkreis zum 30.06.2015 insgesamt 178.758 Einwohner, was einer durchschnittlichen Ein- wohnerdichte von 79 EW/km² entspricht. Die Einwohnerzahl ist somit gegenüber dem Vor- jahr um 1,0% gestiegen. Im Einzelnen sind folgende Werte per 30.06.2015 bekannt: Entwicklung Fläche Einwohner- Verwaltungseinheit Einwohner gegenüber Vj. [km²] dichte [%] [EW/km²] Amt Brieskow-Finkenheerd 7.609 99,9 93,4 81,47 Amt Neuzelle 6.557 99,7 184,3 35,58 Amt Odervorland 5.717 100,4 180,1 31,74 Amt Scharmützelsee 9.134 101,1 124,5 73,36 Amt Schlaubetal 9.811 99,9 297,6 32,96 Amt Spreenhagen 8.186 100,6 173,9 47,07 Stadt Beeskow 8.003 100,4 77.8 102,87 Stadt Eisenhüttenstadt 27.909 103,5 63,5 439,51 Stadt Erkner 11.570 100,2 16,5 701,21 Stadt Friedland 3.002 98,8 174,2 17,23 Stadt Fürstenwalde/Spree 31.484 101,5 70,7 445,32 Stadt Storkow (Mark) 8.919 100,0 180,7 49,36 Gemeinde Grünheide (Mark) 8.219 101,5 126,9 64,77 Gemeinde Rietz-Neuendorf 4.109 99,6 184,8 22,23 Gemeinde Schöneiche b. Bln. 12.168 100,5 16,7 728,62 Gemeinde Steinhöfel 4.380 100,0 160,5 27,29 Gemeinde Tauche 3.885 100,0 121,6 31,95 Gemeinde Woltersdorf 8.096 101,5 9,1 889,67 Seite 1 Breitbandausbau im Landkreis Oder-Spree Markterkundungsverfahren Anlage 1: Ausbaugebiet -

Discrimination and Law in Nazi Germany

Cohen Center for Holocaust and Genocide Studies Name:_______________________________ at Keene State College __________________________________________________________________________________________________ “To Remember…and to Teach.” www.keene.edu/cchgs Student Outline: Destroying Democracy From Within (1933-1938) 1. In the November 1932 elections the Nazis received _______ (%) of the vote. 2. Hitler was named Chancellor of a right-wing coalition government on _________________ _____, __________. 3. Hitler’s greatest fear is that he could be dismissed by President ____________________________. 4. Hitler’s greatest unifier of the many conservatives was fear of the _____________. 5. The Reichstag Fire Decree of February 1933 allowed Hitler to use article _______ to suspend the Reichstag and suspend ________________ ____________ for all Germans. 6. In March 5, 1933 election, the Nazi Party had _________ % of the vote. 7. Concentration camps (KL) emerged from below as camps for “__________________ ________________” prisoners. 8. On March 24, 1933, the _______________ Act gave Hitler power to rule as dictator during the declared “state of emergency.” It was the __________________ Center Party that swayed the vote in Hitler’s favor. 9. Franz Schlegelberger became the State Secretary in the German Ministry of ___________________. He believed that the courts role was to maintain ________________ __________________. He based his rulings on the principle of the ____________________ ___________________ order. He endorsed the Enabling Act because the government, in his view, could act with _______________, ________________, and _____________________. 10. One week after the failed April 1, 1933 Boycott, the Nazis passed the “Law for the Restoration of the Professional _________________ ______________________. The April 11 supplement attempted to legally define “non-Aryan” as someone with a non-Aryan ____________________ or ________________________. -

Spreentdecker Nach Bestaunen, Zu Sakramentenhaus 500-Jährige Werden

Landmarks: Mediahaus GmbH (Lena Bukatz) (Lena GmbH Mediahaus Landmarks: nach Fürstenwalde nach Probieren Sie auch das aktuelle Rathausbräu. aktuelle das auch Sie Probieren Zeichnung: sf-illustrationen Zeichnung: www.kulturverein-nord.de historischen Ratskeller bestaunt werden. werden. bestaunt Ratskeller historischen Illustrationen von Erkner über Grünheide Grünheide über Erkner von T : 03361 340000 03361 : Brauereien mit ihrem Einfluss bis Japan kann im im kann Japan bis Einfluss ihrem mit Brauereien Mit dem Rad...: F.T.V. / G. Mahlkow G. / F.T.V. Rad...: dem Mit Julius-Pintsch-Ring 13, 15517 F 15517 13, Julius-Pintsch-Ring ürstenwalde/Spree Ausflugstipps www.fuerstenwalde-tourismus.de Die bedeutende Geschichte der Fürstenwalder Fürstenwalder der Geschichte bedeutende Die rismus | Auf dem Wasser...: Gemeinde Grünheide (Mark) / Wenke Mellmann | | Mellmann Wenke / (Mark) Grünheide Gemeinde Wasser...: dem Auf | rismus = Di 13–17 Uhr | Mi 13–21 Uhr | Sa 10–13 Uhr 10–13 Sa | Uhr 13–21 Mi | Uhr 13–17 Di T: 03361 760600 03361 T: Menschen, Schätze & Bier-Geschichte(n). Bier-Geschichte(n). & Schätze Menschen, de Grünheide (Mark) | T4: Netzwerk Kulturtourismus | T5 Netzwerk Kulturtou- Netzwerk T5 | Kulturtourismus Netzwerk T4: | (Mark) Grünheide de Mühlenstrasse 1, 15517 Fürstenwalde/Spree 15517 1, Mühlenstrasse ruriuemi le athaus R Alten im Brauereimuseum F3 T1: Stadt Erkner | T2: Seenland Oder-Spree e.V. / Florian Läufer | T3: Gemein- T3: | Läufer Florian / e.V. Oder-Spree Seenland T2: | Erkner Stadt T1: derung. Persönliche Beratung Mo–Fr 10–18 Uhr | Sa 10–14 Uhr 10–14 Sa | Uhr 10–18 Mo–Fr Beratung Persönliche Fotonachweis Kartenseite Fotonachweis - Herausfor seine jeder findet Freizeitkeramikwerkstatt Fürstenwalder Tourismusverein e.V. Tourismusverein Fürstenwalder Anfänger und Fortgeschrittene. -

16 November 2018 in Bonn, Germany

United Nations/Germany High Level Forum: The way forward after UNISPACE+50 and on Space2030 13 – 16 November 2018 in Bonn, Germany USEFUL INFORMATION FOR PARTICIPANTS Content: 1. Welcome to Bonn! ..................................................................................................................... 2 2. Venue of the Forum and Social Event Sites ................................................................................. 3 3. How to get to the Venue of the Forum ....................................................................................... 4 4. How to get to Bonn from International Airports ......................................................................... 5 5. Visa Requirements and Insurance .............................................................................................. 6 6. Recommended Accommodation ............................................................................................... 6 7. General Information .................................................................................................................. 8 8. Organizing Committe ............................................................................................................... 10 Bonn, Rhineland Germany Bonn Panorama © WDR Lokalzeit Bonn 1. Welcome to Bonn! Bonn - a dynamic city filled with tradition. The Rhine and the Rhineland - the sounds, the music of Europe. And there, where the Rhine and the Rhineland reach their pinnacle of beauty lies Bonn. The city is the gateway to the romantic part of -

Der Alte Tiergarten Und Die Galleien Zu Kleve Den Himmel Auf Die Erde

Das Parkpflegewerk Alter Tiergarten – Wiederbelebung der historischen Parkanlagen des Fürsten Johann Moritz von Nassau-Siegen Das Parkpflegewerk Alter Tiergarten – Wiederbelebung der historischen Parkanlagen des Fürsten Johann Moritz von Nassau-Siegen Kulturerbe erhalten Europäische Gartenkunst Denkmal Alter Tiergarten Kleve Deutsch-Niederländisches Kulturerbe Alter Tiergarten mit Zukunft Neuer Tiergarten Die außerordentliche Bedeutung der historischen Klever Parkanlagen im Rahmen der europäischen Gartenkunst hat der Landschaftsverband Rheinland, Amt für Denkmalpflege im Rheinland amtlich bestätigt. Quellenlage – Die Klever Gartenanlagen gehören aufgrund Den Himmel auf der zahlreich vorliegenden fundierten wissenschaftlichen Untersuchungen sicher zu den am besten erforschten und – flex-on.net Frauenlob Christoph und Titelfoto: Layout die Erde holen dokumentierten Europäischen Gartenanlagen. Lustgarten · Orangerie · Tiergarten Bürgerstolz – Durch den tatkräftigen Einsatz von Bürgern, Behörden, Unternehmen, Stiftungen und Vereinen konnten in Das halbkreisförmige Moritzgrabmal zu Berg und Tal Erhalt Europäischer Gartenkunst – Schon 1976 betont das den letzten Jahren erste Schritte für eine Wiederherstellung Gut achten der Gartenhistoriker Hennebo und Hoffmann „Histo- der historischen Anlagen vor der Stadtsilhouette erreicht werden. rische und aktuelle Bedeutung der klevischen Gartenanlagen Dank – Der Arbeitskreis dankt für die Unterstützung, auch des Fürsten Johann Moritz von Nassau-Siegen“ die Bedeutung für das Interesse unserer niederländischen -

When Architecture and Politics Meet

Housing a Legislature: When Architecture and Politics Meet Russell L. Cope Introduction By their very nature parliamentary buildings are meant to attract notice; the grander the structure, the stronger the public and national interest and reaction to them. Parliamentary buildings represent tradition, stability and authority; they embody an image, or the commanding presence, of the state. They often evoke ideals of national identity, pride and what Ivor Indyk calls ‘the discourse of power’.1 In notable cases they may also come to incorporate aspects of national memory. Consequently, the destruction of a parliamentary building has an impact going beyond the destruction of most other public buildings. The burning of the Reichstag building in 1933 is an historical instance, with ominous consequences for the German State.2 Splendour and command, even majesty, are clearly projected in the grandest of parliamentary buildings, especially those of the Nineteenth Century in Europe and South America. Just as the Byzantine emperors aimed to awe and even overwhelm the barbarian embassies visiting their courts by the effects of architectural splendour and 1 Indyk, I. ‘The Semiotics of the New Parliament House’, in Parliament House, Canberra: a Building for the Nation, ed. by Haig Beck, pp. 42–47. Sydney, Collins, 1988. 2 Contrary to general belief, the Reichstag building was not destroyed in the 1933 fire. The chamber was destroyed, but other parts of the building were left unaffected and the very large library continued to operate as usual. A lot of manipulated publicity by the Nazis surrounded the event. Full details can be found in Gerhard Hahn’s work cited at footnote 27. -

Berlin Is the Capital of Germany and Was the Capital of the Former Kingdom of Prussia

Berlin is the capital of Germany and was the capital of the former kingdom of Prussia. After World War II, Berlin was divided, and in 1961, the Berlin Wall was built. But the wall fell in 1989, and the country became one again in 1990. ©2015 Bonnie Rose Hudson WriteBonnieRose.com ////////////////////////////////////////////////////// ////////////////////////////////////////////////////// ////////////////////////////////////////////////////// ////////////////////////////////////////////////////// ////////////////////////////////////////////////////// ////////////////////////////////////////////////////// ////////////////////////////////////////////////////// ////////////////////////////////////////////////////// ////////////////////////////////////////////////////// ////////////////////////////////////////////////////// ////////////////////////////////////////////////////// ////////////////////////////////////////////////////// ////////////////////////////////////////////////////// ©2015 Bonnie Rose Hudson WriteBonnieRose.com Cologne/is/in/a/region/of/Germany/called/the/ Rhineland./Its/biggest/and/most/famous//////// building/is/the/Cologne/Cathedral,/a/giant///// church/that/stretches/515/feet/high!/Inside///// the/church/you/can/find/many/beautiful//////// pieces/of/art,/some/more/than/500/years/old./ Cologne/is/in/a/region/of/Germany/called/the/ Rhineland./Its/biggest/and/most/famous//////// building/is/the/Cologne/Cathedral,/a/giant///// church/that/stretches/515/feet/high!/Inside///// the/church/you/can/find/many/beautiful//////// -

Closer to Europe — Tremendous Opportunities Close By: Germany Is Applying Interview – a Conversation with Bfarm Executive Director Prof

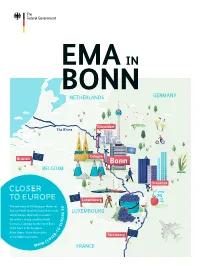

CLOSER TO EUROPE The new home of the European Medicines U E Agency (EMA) should be located centrally . E within Europe. Optimally accessible. P Set within a strong neigh bourhood. O R Germany is applying for the city of Bonn, U E at the heart of the European - O T Rhine Region, to be the location - R E of the EMA’s new home. S LO .C › WWW FOREWORD e — Federal Min öh iste Gr r o nn f H a e rm al e th CLOSER H TO EUROPE The German application is for a very European location: he EU 27 will encounter policy challenges Healthcare Products Regulatory Agency. The Institute Bonn. A city in the heart of Europe. Extremely close due to Brexit, in healthcare as in other ar- for Quality and Efficiency in Health Care located in T eas. A new site for the European Medicines nearby Cologne is Europe’s leading institution for ev- to Belgium, the Netherlands, France and Luxembourg. Agency (EMA) must be found. Within the idence-based drug evaluation. The Paul Ehrlich Insti- Situated within the tri-state nexus of North Rhine- EU, the organisation has become the primary centre for tute, which has 800 staff members and is located a mere drug safety – and therefore patient safety. hour and a half away from Bonn, contributes specific, Westphalia, Hesse and Rhineland-Palatinate. This is internationally acclaimed expertise on approvals and where the idea of a European Rhine Region has come to The EMA depends on close cooperation with nation- batch testing of biomedical pharmaceuticals and in re- life. -

Art Lover's: Berlin

THE GALLERY COUNCIL OF THE MEMORIAL ART GALLERY PRESENTS Art Lover’s: Berlin September 9 - 15, 2020 We invite you to join us for an extraordinary opportunity to explore the cultural capital of Europe on a 5-night program to Berlin. Led by Art Historian, Fiona Bennett, we will dive into the vibrant art scene as we discover both the old masters and the contemporary visionaries which make Berlin one of the great destinations for art lovers. Set during Berlin Art Week, our program will feature visits to special exhibitions and galleries as Berlin transforms into a hub for contemporary art where German and international artists come together. We will step out of the city on excursions to see Frederick the Great’s extraordinary Sanssouci Palace in Potsdam and to the charming cities of Lehde and Lübbenau, set within the UNESCO-protected Spreewald. Our leisurely paced program will allow you plenty of free time on your own to explore the many museums and cultural sites throughout Berlin at your leisure. Tour Highlights Discover Yayoi Kusama’s instillation Visit special gallery and exhibition at Martin-Gropius-Bau openings during Berlin Art Week Spend an afternoon exploring Enjoy an intimate evening concert at Berlin’s Museum Island the Piano Salon Christophori Enjoy an evening cruise along the Take a guided tour of the East Side River Spree Gallery, once part of the Berlin Wall Take a traditional punt boat to the Marvel at the Schloss Sanssouci palace picturesque town of Lehde in Potsdam ACCOMMODATIONS Berlin: 5 nights Berlin Marriott Hotel For more information or detailed itinerary please contact: Michelle Turner at (585) 747- 1547 or [email protected] The Memorial Art Gallery’s tour operator, Distant Horizons, is a California Seller of Travel (CST #2046776 -40) and a participant in the California Travel Restitution Fund.