Uncovering REDD+ Readiness in Mexico: Actors, Discourses and Benefit-Sharing

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Delegate List

About CTBUH The Council on Tall Buildings and Urban Habitat (CTBUH) is the world’s leading resource for professionals focused on the inception, design, construction, and operation of tall buildings and future cities. Founded in 1969 and headquartered at Chicago’s historic Monroe Building, the CTBUH is a not-for-profit organization with an Asia Headquarters office at Tongji University, Shanghai; a Research Office at Iuav University, Venice, Italy; and an Academic Office at the Illinois Institute of Technology, Chicago. CTBUH facilitates the exchange of the latest knowledge available on tall buildings around the world through publications, research, events, working groups, web resources, and its extensive network of international representatives. The Council’s research department is spearheading the investigation of the next generation of tall buildings by aiding original Dubai & Abu Dhabi, UAE | 20–25 October research on sustainability and key development issues. The Council’s free database on tall buildings, The Skyscraper Center, is updated daily with detailed information, images, data, and news. The CTBUH also developed the international standards for measuring tall building height and is recognized as the arbiter for bestowing such designations as “The World’s Tallest Building.” Delegate List www.ctbuh.org | www.skyscrapercenter.com ctbuh2018.org #CTBUH2018 CTBUH2018_DelegateList_Cover.indd 2-3 10/12/2018 4:40:55 PM Many Thanks to All of Our Sponsors Delegate List: What’s Inside? Diamond Attendance Analysis 3 Top Regions & Companies Represented Delegate List by Company 6 Listed Alphabetically by Affi liation Platinum Delegate List by Surname 26 Listed Alphabetically by Surname Gold 1300+ DELEGATES 278 PRESENTERS 27 OFF-SITE WME consultants PROGRAMS 8 TRACKS Silver 4 1 EVENINGS OF GREAT RECEPTIONS SYMPOSIUMS 3 CONFERENCE! PROGRAM ROOMS 5 SPONSORS 68 128 CITIES 447 COMPANIES Bronze Supported By: COUNTRIES 54 2 Representation by Region Note: This registration list includes the 1240 delegates that were registered by Monday 8 October. -

Quarterly Report on the Euro Area (QREA), Vol. 19, No. 1

ISSN 2443-8014 (online) Quarterly Report on the Euro Area Volume 19, No 1 (2020) • Shifting taxes away from labour to strengthen growth in the euro area. Section prepared by E. Meyermans, A. Leodolter, L. Pires, S. Princen and A. Rutkowski • Assessing public debt sustainability: some insights from an EU perspective into an inexorable question. Section prepared by S. Pamies and A. Reut • The sovereign-bank nexus in the euro area: financial and real channels. Section prepared by M. Bellia, L. Cales, L. Frattarolo, A. Maerean, D. Monteiro, M. P. Giudici and L. Vogel • The natural rate of unemployment and its institutional determinants. Section prepared by A. Hristov and W. Roeger INSTITUTIONAL PAPER 130 | JUNE 2020 EUROPEAN ECONOMY Economic and Financial Affairs The Quarterly Report on the Euro Area is written by staff of the Directorate-General for Economic and Financial Affairs. It is intended to contribute to a better understanding of economic developments in the euro area and to improve the quality of the public debate surrounding the area's economic policy. The views expressed are the author’s alone and do not necessarily correspond to those of the European Commission. The Report is released every quarter of the year. Editors: Jose Eduardo Leandro, Gabriele Giudice Coordination: Zenon Kontolemis, Eric Meyermans Statistical and layout assistance: Despina Efthimiadou, Dris Rachik The editorial team thanks the reviewers of the 2019 QREA edition for their valuable comments and efforts towards improving the manuscripts. More particularly, they would like to thank Emrah Arbak, Erik Canton, Leonor Coutinho, Mirzha De Manuel, Christian Engelen, Roman Garcia, Anton Jevcak, Peter Koh, Davide Lombardo, Daniel Monteiro, Plamen Nikolov, Leonor Pires, Karl Scerri, Jonas Sebhatu, Guergana Stanoeva, Anna Thum-Thysen, Chris Uregian, Lukas Vogel and Marcin Zogala. -

Understanding and Improving the Identification of Somatic Variants

Understanding and Improving the Identification of Somatic Variants Vinaya Vijayan Dissertation submitted to the faculty of the Virginia Polytechnic Institute and State University in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy In Genetics, Bioinformatics and Computational Biology Chair: Liqing Zhang Christopher Franck Lenwood S. Heath Xiaowei Wu August 12th, 2016 Blacksburg, VA, USA Keywords: Somatic variants, Somatic variant callers, Somatic point mutations, Short tandem repeat variation, Lung squamous cell carcinoma Understanding and Improving the Identification of Somatic Variants Vinaya Vijayan ABSTRACT It is important to understand the entire spectrum of somatic variants to gain more insight into mutations that occur in different cancers for development of better diagnostic, prognostic and therapeutic tools. This thesis outlines our work in understanding somatic variant calling, improving the identification of somatic variants from whole genome and whole exome platforms and identification of biomarkers for lung cancer. Integrating somatic variants from whole genome and whole exome platforms poses a challenge as variants identified in the exonic regions of the whole genome platform may not be identified on the whole exome platform and vice-versa. Taking a simple union or intersection of the somatic variants from both platforms would lead to inclusion of many false positives (through union) and exclusion of many true variants (through intersection). We develop the first framework to improve the identification of somatic variants on whole genome and exome platforms using a machine learning approach by combining the results from two popular somatic variant callers. Testing on simulated and real data sets shows that our framework identifies variants more accurately than using only one somatic variant caller or using variants from only one platform. -

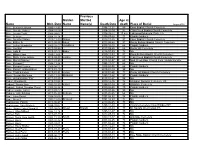

Name Obit. Date Maiden Name Previous Married Name(S) Death Date Age at Death Place of Burial

Previous Maiden Married Age at Name Obit. Date Name Name(s) Death Date death Place of Burial August 2018 Pace, Benjamin Brown 1996-11-25 1996-11-21 80 Enon Baptist Church Cemetery Pace, Claudie Volney 2004-10-18 2004-10-14 92 Crab Creek Baptist Church Cemetery Pace, Curran Todd 2006-09-07 2006-08-22 10 mo Lakewood Memorial Park, CA Pace, Delmore 2008-07-14 2008-07-08 71 Pisgah Gardens Pace, Dorothy Staton 2012-11-29 Staton 2012-11-25 97 Enon Baptist Church Cemetery Pace, Esther A. 2011-05-30 Aiken 2011-05-28 97 Rocky Bottom Baptist Church Cemetery Pace, JoAnn Hendricks 2003-10-13 Hendricks 2003-10-10 64 Pisgah Gardens Pace, Joe Earl 2017-09-25 2017-09-20 82 Rocky Hill Cemetery Pace, Judy B. 2015-07-13 Baker 2015-07-09 73 NA Pace, Milton Clark 2000-11-06 2000-11-04 87 Rock Bottom Baptist Church Cemetery Pace, Mollie Irene Justice 2010-09-30 Justice 2010-09-27 88 Crab Creek Baptist Church Cemetery Pace, Morris Pinkney 2014-01-20 2014-01-07 60 Mud Creek Bap, Church Cem, Hendersonville Pace, Richard G. 1994-11-24 1994-11-17 65 NA Pace, Richard Vernon 1988-04-11 1988-04-08 62 Pisgah Gardens Pace, Rosa F. Hildegardner 2015-01-19 2015-01-14 90 NA Pace, Thelma Jones 2013-01-21 Jones 2013-01-20 71 Rocky Hill Baptist Church Cemetery Pacer, Beulah McGuinn 1991-11-28 McGuinn 1991-11-22 87 Pisgah Gardens Pack, Richard Allan "Pig" 2017-01-30 2017-01-27 52 NA Paden, Douglas R. -

In Re Johnson & Johnson Talcum Powder Prods. Mktg., Sales

Neutral As of: May 5, 2020 7:00 PM Z In re Johnson & Johnson Talcum Powder Prods. Mktg., Sales Practices & Prods. Litig. United States District Court for the District of New Jersey April 27, 2020, Decided; April 27, 2020, Filed Civil Action No.: 16-2738(FLW), MDL No. 2738 Reporter 2020 U.S. Dist. LEXIS 76533 * MONTGOMERY, AL; CHRISTOPHER MICHAEL PLACITELLA, COHEN, PLACITELLA & ROTH, PC, IN RE: JOHNSON & JOHNSON TALCUM POWDER RED BANK, NJ. PRODUCTS MARKETING, SALES PRACTICES AND PRODUCTS LITIGATION For ADA RICH-WILLIAMS, 16-6489, Plaintiff: PATRICIA LEIGH O'DELL, LEAD ATTORNEY, COUNSEL NOT ADMITTED TO USDC-NJ BAR, MONTGOMERY, AL; Prior History: In re Johnson & Johnson Talcum Powder Richard Runft Barrett, LEAD ATTORNEY, COUNSEL Prods. Mktg., Sales Practices & Prods. Liab. Litig., 220 NOT ADMITTED TO USDC-NJ BAR, LAW OFFICES F. Supp. 3d 1356, 2016 U.S. Dist. LEXIS 138403 OF RICHARD L. BARRETT, PLLC, OXFORD, MS; (J.P.M.L., Oct. 5, 2016) CHRISTOPHER MICHAEL PLACITELLA, COHEN, PLACITELLA & ROTH, PC, RED BANK, NJ. For DOLORES GOULD, 16-6567, Plaintiff: PATRICIA Core Terms LEIGH O'DELL, LEAD ATTORNEY, COUNSEL NOT ADMITTED TO USDC-NJ BAR, MONTGOMERY, AL; studies, cancer, talc, ovarian, causation, asbestos, PIERCE GORE, LEAD ATTORNEY, COUNSEL NOT reliable, Plaintiffs', cells, talcum powder, ADMITTED TO USDC-NJ BAR, PRATT & epidemiological, methodology, cohort, dose-response, ASSOCIATES, SAN JOSE, CA; CHRISTOPHER unreliable, products, biological, exposure, case-control, MICHAEL PLACITELLA, COHEN, PLACITELLA & Defendants', relative risk, testing, scientific, opines, ROTH, PC, RED BANK, [*2] NJ. inflammation, consistency, expert testimony, in vitro, causes, laboratory For TOD ALAN MUSGROVE, 16-6568, Plaintiff: AMANDA KATE KLEVORN, LEAD ATTORNEY, PRO HAC VICE, COUNSEL NOT ADMITTED TO USDC-NJ Counsel: [*1] For HON. -

Congressional Record United States Th of America PROCEEDINGS and DEBATES of the 115 CONGRESS, FIRST SESSION

E PL UR UM IB N U U S Congressional Record United States th of America PROCEEDINGS AND DEBATES OF THE 115 CONGRESS, FIRST SESSION Vol. 163 WASHINGTON, TUESDAY, APRIL 25, 2017 No. 70 House of Representatives The House met at noon and was Of course, understanding our system by emitting an unprecedented volume called to order by the Speaker pro tem- of government means understanding of hot air. pore (Mr. MESSER). the U.S. Constitution. It is the greatest Now, a week earlier we had tax day, f gift left to us by the Founders, and it and millions of Americans across this has stood the test of time. country, including in Los Angeles, DESIGNATION OF SPEAKER PRO The success of the Constitution is needed to demonstrate to try to get TEMPORE due to its carefully designed system of Donald Trump to reveal his tax re- The SPEAKER pro tempore laid be- checks and balances. By separating the turns. Every President since Richard fore the House the following commu- powers of government into separate Nixon has released their tax returns. nication from the Speaker: but equal branches and guaranteeing Donald Trump told us in May of 2014: If WASHINGTON, DC, individual rights, the Constitution has I decide to run for office, I will produce April 25, 2017. been, as James Madison suggested, my tax returns. And he said it again a I hereby appoint the Honorable LUKE ‘‘the guardian of true liberty.’’ year later. And then he said it during MESSER to act as Speaker pro tempore on Mr. -

Faculty Publications College of Arts & Sciences

Faculty Publications College of Arts & Sciences 42nd Edition, 2010-2011 Faculty Publications 2010-2011 Preface iii Contributions by Department iv Anthropology 1 Biological Sciences 4 Chemistry 17 Chemical Physics 23 Computer Science 27 English 31 Geology 35 History 53 Liberal Studies 56 Mathematical Sciences 57 Modern and Classical Languages 63 Philosophy 66 Physics 67 Political Sciences 72 Psychology 79 Sociology 90 Index of Contributors 95 Preface iii On behalf of the College of Arts and Sciences, I take great pleasure in sending you the Forty-Second Annual List of Faculty Publications, for academic years 2010 and 2011. This list reviews the broad range of faculty interests and lists the accomplishments of the faculty in all areas of publication, specifically the scholarly and research areas. I wish to thank Raymond A. Craig for serving as editor, and Sean Howard and Allyson Brooks for coordinating the collection of the data, for preparation of the document and duplication of the final copy. In addition, I wish to thank all of the departmental members who have cooperated in supplying materials for this listing. This list will be sent to members of the Central Administration, the Vice President for Research, the Dean of Graduate Studies, Departmental Chairpersons, the College Advisory Committee, and the College Curriculum Committee and will be available online at www.kent.edu/CAS/Research/facpubs.cfm. This list of publications includes books, books edited, book reviews, articles, bulletins, review articles, maps, reprintings, audio and video devices, poems, essays, translations, and other works. Complete or nearly complete publication lists for faculty members who have joined the college are included. -

ESREL 2020 PSAM 15 the 30Th European Safety and Reliability Conference the 15Th Probabilistic Safety Assessment and Management Conference

ESREL 2020 PSAM 15 The 30th European Safety and Reliability Conference The 15th Probabilistic Safety Assessment and Management Conference Reliability, safety and security for a truly sustainable world PROGRAM Contents 3 Foreword - Message by the Chairman 4 Foreword - Message by the Technical Chairmen 5 Conference Chairs 6 Technical Committee 9 Organizations, Industrial Partners, Exhibitors 10 Patronage 11 The George Apostolakis Fellowship 12 Fellowship Award Winner 13 Previous ESREL/PSAM Conferences 14 Instructions for Chairs and Speakers 15 Instructions for Virtual Attendance 18 Opening Ceremony 29 Panel: "Risk in practice: smart solutions for sustainable global world" 36 Technical Program 37 Technical Program Tracks 40 Technical Program on Monday, 2 November 2020 41 Technical Program on Tuesday, 3 November 2020 42 Technical Program on Wednesday, 4 November 2020 43 Technical Program on Thursday, 5 November 2020 44 Keynote Speakers 55 Special Sessions 63 Plenary Lectures 68 Panels 71 Innovation Challenges 73 Posters 75 Video and E-Proceedings 124 Next Conferences - 2 - Foreword - Message by the Chairman It is my pleasure to welcome you to the ESREL 2020 PSAM 15 Conference, the 30th European Safety and Reliability (ESREL) Conference and the 15th Probabilistic Safety Assessment and Management (PSAM) Conference, jointly organized by the European Safety and Reliability Association (ESRA) and the International Association of Probabilistic Safety Assessment and Management (IAPSAM). This conference brings together the top experts of the world in the science and practice of reliability and safety. It is a unique World Exposition (a real “Expo Tech”) of scientific methodologies and technical solutions to advance knowledge for the reliable design and operation of components and systems, for the prevention and management of risk in complex systems and critical infrastructures. -

Electron Donors and Acceptors for Members of the Family Beggiatoaceae

Electron donors and acceptors for members of the family Beggiatoaceae Dissertation zur Erlangung des Doktorgrades der Naturwissenschaften - Dr. rer. nat. - dem Fachbereich Biologie/Chemie der Universit¨at Bremen vorgelegt von Anne-Christin Kreutzmann aus Hildesheim Bremen, November 2013 Die vorliegende Doktorarbeit wurde in der Zeit von Februar 2009 bis November 2013 am Max-Planck-Institut f¨ur marine Mikrobiologie in Bremen angefertigt. 1. Gutachterin: Prof. Dr. Heide N. Schulz-Vogt 2. Gutachter: Prof. Dr. Ulrich Fischer 3. Pr¨uferin: Prof. Dr. Nicole Dubilier 4. Pr¨ufer: Dr. Timothy G. Ferdelman Tag des Promotionskolloquiums: 16.12.2013 To Finn Summary The family Beggiatoaceae comprises large, colorless sulfur bacteria, which are best known for their chemolithotrophic metabolism, in particular the oxidation of re- duced sulfur compounds with oxygen or nitrate. This thesis contributes to a more comprehensive understanding of the physiology and ecology of these organisms with several studies on different aspects of their dissimilatory metabolism. Even though the importance of inorganic sulfur substrates as electron donors for the Beggiatoaceae has long been recognized, it was not possible to derive a general model of sulfur compound oxidation in this family, owing to the fact that most of its members can currently not be cultured. Such a model has now been developed by integrating information from six Beggiatoaceae draft genomes with available literature data (Section 2). This model proposes common metabolic pathways of sulfur compound oxidation and evaluates whether the involved enzymes are likely to be of ancestral origin for the family. In Section 3 the sulfur metabolism of the Beggiatoaceae is explored from a dif- ferent perspective. -

PHYSICS PUBLICATIONS JLAB NUMBER TITLE of PAPER AUTHOR(S) Published? Year Month JOURNAL REFERENCE Published FY09 AFTER Science and Technology Review

PHYSICS PUBLICATIONS JLAB NUMBER TITLE OF PAPER AUTHOR(S) Published? Year month JOURNAL REFERENCE Published FY09 AFTER Science and Technology Review JLAB-PHY-08-872 Measurement of unpolarized semi-inclusive pi+ M. Osipenko, M. Ripani, G. Ricco, H. Avakian, R. De Vita, G. Yes 2009 August Phys.Rev.D80:032004,2009 electroproduction off the proton Adams, M.J. Amaryan, P. Ambrozewicz, M. Anghinolfi, G. Asryan, G. Audit, H. Bagdasaryan, N. Baillie, J.P. Ball, N.A. Baltzell, S. Barrow, M. Battaglieri, I. Bedlinskiy, M. Bektasoglu, M. Bellis, N. Benmouna, B.L. Berman, A.S. Biselli, L. Blaszczyk, B.E. Bonner, S. Bouchigny, S. Boiarinov, R. Bradford, D. Branford, W.J. Briscoe, W.K. Brooks, S. Bueltmann, V.D. Burkert, C. Butuceanu, J.R. Calarco, S.L. Careccia, D.S. Carman, A. Cazes, F. Ceccopieri, S. Chen, P.L. Cole, P. Collins, P. Coltharp, P. Corvisiero, D. Crabb, V. Crede, J.P. Cummings, N. Dashyan, R. De Masi, E. De Sanctis, P.V. Degtyarenko, H. Denizli, L. Dennis, A. Deur, K.V. Dharmawardane, K.S. Dhuga, R. Dickson, C. Djalali, G.E. Dodge, J. Donnelly, D. Doughty V. Drozdov, M. Dugger, S. Dytman, O.P. Dzyubak, H. Egiyan, K.S. Egiyan, L. El Fassi, L. Elouadrhiri, P. Eugenio, R. Fatemi, G. Fedotov, G. Feldman, R.J. Feuerbach, H. Funsten, M. Gar¸con, G. Gavalian G.P. Gilfoyle, K.L. Giovanetti, F.X. Girod, J.T. Goetz, E. Golovach, A. Gonenc, C.I.O. Gordon, R.W. Gothe, K.A. Griffioen, M. Guidal, M. Guillo, N. Guler, L. Guo, V. Gyurjyan, C. -

Significance for Aging and Neurodegeneration

Molecular Neurobiology (2019) 56:3501–3521 https://doi.org/10.1007/s12035-018-1286-3 The Cross-Talk Between Sphingolipids and Insulin-Like Growth Factor Signaling: Significance for Aging and Neurodegeneration Henryk Jęśko1 & Adam Stępień2 & Walter J. Lukiw3 & Robert P. Strosznajder4 Received: 31 May 2018 /Accepted: 25 July 2018 /Published online: 23 August 2018 # The Author(s) 2018 Abstract Bioactive sphingolipids: sphingosine, sphingosine-1-phosphate (S1P), ceramide, and ceramide-1-phosphate (C1P) are increas- ingly implicated in cell survival, proliferation, differentiation, and in multiple aspects of stress response in the nervous system. The opposite roles of closely related sphingolipid species in cell survival/death signaling is reflected in the concept of tightly controlled sphingolipid rheostat. Aging has a complex influence on sphingolipid metabolism, disturbing signaling pathways and the properties of lipid membranes. A metabolic signature of stress resistance-associated sphingolipids correlates with longevity in humans. Moreover, accumulating evidence suggests extensive links between sphingolipid signaling and the insulin-like growth factor I (IGF-I)-Akt-mTOR pathway (IIS), which is involved in the modulation of aging process and longevity. IIS integrates a wide array of metabolic signals, cross-talks with p53, nuclear factor κB (NF-κB), or reactive oxygen species (ROS) and influences gene expression to shape the cellular metabolic profile and stress resistance. The multiple connections between sphingolipids and IIS signaling suggest possible engagement of these compounds in the aging process itself, which creates a vulnerable background for the majority of neurodegenerative disorders. Keywords Ceramide . Sphingosine-1-phosphate . Aging . Neurodegeneration . Insulin-like growth factor . Mitochondria Sphingolipid Biosynthesis and Signaling reflected in the concept of highly regulated sphingolipid rheostat and justifies their vast importance in aging and neurodegenera- Bioactive sphingolipids: ceramide, ceramide-1-phosphate tion [3, 4]. -

Acknowledgment to Reviewers of Mathematics in 2020

Editorial Acknowledgment to Reviewers of Mathematics in 2020 Mathematics Editorial Office MDPI AG, St. Alban-Anlage 66, 4052 Basel, Switzerland Peer review is the driving force of journal development, and reviewers are gatekeepers who ensure that Mathematics maintains its standards for the high quality of its published papers. Thanks to the cooperation of our reviewers, in 2020, the median time to first deci- sion was 17 days and the median time to publication was 35 days. The editors would like to express their sincere gratitude to the following reviewers for their precious time and dedication, regardless of whether the papers were finally published: Aase, Reyes Ahmadieh Khanesar, Mojtaba Abad-Segura, Emilio Ahmadpoor, Fatemeh Abali, Bilen Emek Ahmed, Hafiz Abdel Wahab, Omar Ahmed, Muhammad Usman Abdelghani, Mohamed Ahmed, Osama Abdellatif, Alaa Awad Ahn, Sun Shin Abdul Wahab, Omar Ahsan, Md Mominul Abdul-Aziz, Ali Aichinger, Erhard Abdul-Rahman, Houssam Ait Haddou, Rachid Abellán, Joaquín Akanji, Lateef Abodayeh, Kamal Akdemir, Ahmet Aboura, Sofiane Akın, Elvan Abpeikar, Shadi Akin, Ethan Abramov, Viktor Akinsolu, Mobayode O. Abramovic, Borna Akkermans, Rinie Citation: Mathematics Editorial Abreu, António Akram, Muhammad Office. Acknowledgment to Abundo, Mario Aktas, Mehmet Reviewers of Mathematics in 2020. Aceves, Alejandro B. Al Basheer, Aladeen Mathematics 2021, 9, 196. Acu, Mugur Al Ghour, Samer https://doi.org/10.3390/math9020196 Adam, Deptuła Alamaniotis, Miltiadis Adam, Marcin Alanqar, Anas Published: 19 January 2021 Adam, Maria C. Al-Anssari, Sarmad Adamson, Matthew Alapati, Suresh Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neu- tral with regard to jurisdictional Addabbo, Raymond Alb Lupas, A. claims in published maps and institu- Adegoke, Nurudeen Albano, Giuseppina tional affiliations.