How the Roles of Advertising Merely Appear to Have Changed John R

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

2021 Catalog

2021 NEW PRODUCTS G-Power Flip and Punch Spin Bait Designed by Aaron Martens, Walleye anglers across the Midwest have become Gamakatsu has developed the dependent upon the spin style hooks for walleye rigs. new G-Power Heavy Cover Flip The Spin Bait hook can be rigged behind spinner & Punch Hook. A step up from blades, prop blades or used the G-Finesse Heavy Cover alone with just a simple Hook, for serious flipping and bead in front of them. It’s punching with heavy fluorocarbon and braid. The TGW (Tournament unique design incorporates Grade Wire) hook, paired with its welded eye, make this the strongest Gamakatsu swivels that is Heavy Cover hook in Gamakatsu’s G-Series lineup. Ideal for larger baits independent of the hook, giving the hook more freedom to spin while and weights, punching through grass mats and flipping into heavy reducing line twist. The Spin Bait hook features Nano Smooth Coat for timber. G-Power Flip and Punch ideally matches to all types of cover stealth presentations and unsurpassed hook penetration and the bait and able to withstand extreme conditions. Page 26 keeper barbs on the shank hold live and plastic baits on more securely. Page 48 G-Power Stinger Trailer Hook The new G-Power Stinger Trailer Hook Superline Offset Round Bend brilliance comes from Gamakatsu’s famous Gamakatsu’s Superline Offset Round B10S series of fly hooks and the expertise Bend is designed with a heavier of Professional Bass angler Aaron Martens. Superline wire best suited for heavy The Stinger Trailer has a strategically braided and fluorocarbon lines. -

Rolling Stone Magazine's Top 500 Songs

Rolling Stone Magazine's Top 500 Songs No. Interpret Title Year of release 1. Bob Dylan Like a Rolling Stone 1961 2. The Rolling Stones Satisfaction 1965 3. John Lennon Imagine 1971 4. Marvin Gaye What’s Going on 1971 5. Aretha Franklin Respect 1967 6. The Beach Boys Good Vibrations 1966 7. Chuck Berry Johnny B. Goode 1958 8. The Beatles Hey Jude 1968 9. Nirvana Smells Like Teen Spirit 1991 10. Ray Charles What'd I Say (part 1&2) 1959 11. The Who My Generation 1965 12. Sam Cooke A Change is Gonna Come 1964 13. The Beatles Yesterday 1965 14. Bob Dylan Blowin' in the Wind 1963 15. The Clash London Calling 1980 16. The Beatles I Want zo Hold Your Hand 1963 17. Jimmy Hendrix Purple Haze 1967 18. Chuck Berry Maybellene 1955 19. Elvis Presley Hound Dog 1956 20. The Beatles Let It Be 1970 21. Bruce Springsteen Born to Run 1975 22. The Ronettes Be My Baby 1963 23. The Beatles In my Life 1965 24. The Impressions People Get Ready 1965 25. The Beach Boys God Only Knows 1966 26. The Beatles A day in a life 1967 27. Derek and the Dominos Layla 1970 28. Otis Redding Sitting on the Dock of the Bay 1968 29. The Beatles Help 1965 30. Johnny Cash I Walk the Line 1956 31. Led Zeppelin Stairway to Heaven 1971 32. The Rolling Stones Sympathy for the Devil 1968 33. Tina Turner River Deep - Mountain High 1966 34. The Righteous Brothers You've Lost that Lovin' Feelin' 1964 35. -

Weight and Lifestyle Inventory (Wali)

WEIGHT AND LIFESTYLE INVENTORY (Bariatric Surgery Version) © 2015 Thomas A. Wadden, Ph.D. and Gary D. Foster, Ph.D. 1 The Weight and Lifestyle Inventory (WALI) is designed to obtain information about your weight and dieting histories, your eating and exercise habits, and your relationships with family and friends. Please complete the questionnaire carefully and make your best guess when unsure of the answer. You will have an opportunity to review your answers with a member of our professional staff. Please allow 30-60 minutes to complete this questionnaire. Your answers will help us better identify problem areas and plan your treatment accordingly. The information you provide will become part of your medical record at Penn Medicine and may be shared with members of our treatment team. Thank you for taking the time to complete this questionnaire. SECTION A: IDENTIFYING INFORMATION ______________________________________________________________________________ 1 Name _________________________ __________ _______lbs. ________ft. ______inches 2 Date of Birth 3 Age 4 Weight 5 Height ______________________________________________________________________________ 6 Address ____________________ ________________________ ______________________/_______ yrs. 7 Phone: Cell 8 Phone: Home 9 Occupation/# of yrs. at job __________________________ 10 Today’s Date 11 Highest year of school completed: (Check one.) □ 6 □ 7 □ 8 □ 9 □ 10 □ 11 □ 12 □ 13 □ 14 □ 15 □ 16 □ Masters □ Doctorate Middle School High School College 12 Race (Check all that apply): □ American Indian □ Asian □ African American/Black □ Pacific Islander □White □ Other: ______________ 13 Are you Latino, Hispanic, or of Spanish origin? □ Yes □ No SECTION B: WEIGHT HISTORY 1. At what age were you first overweight by 10 lbs. or more? _______ yrs. old 2. What has been your highest weight after age 21? _______ lbs. -

Song Lyrics of the 1950S

Song Lyrics of the 1950s 1951 C’mon a my house by Rosemary Clooney Because of you by Tony Bennett Come on-a my house my house, I’m gonna give Because of you you candy Because of you, Come on-a my house, my house, I’m gonna give a There's a song in my heart. you Apple a plum and apricot-a too eh Because of you, Come on-a my house, my house a come on My romance had its start. Come on-a my house, my house a come on Come on-a my house, my house I’m gonna give a Because of you, you The sun will shine. Figs and dates and grapes and cakes eh The moon and stars will say you're Come on-a my house, my house a come on mine, Come on-a my house, my house a come on Come on-a my house, my house, I’m gonna give Forever and never to part. you candy Come on-a my house, my house, I’m gonna give I only live for your love and your kiss. you everything It's paradise to be near you like this. Because of you, (instrumental interlude) My life is now worthwhile, And I can smile, Come on-a my house my house, I’m gonna give you Christmas tree Because of you. Come on-a my house, my house, I’m gonna give you Because of you, Marriage ring and a pomegranate too ah There's a song in my heart. -

Before Using Scale Weight Measurement Only Personal Data

Congratulations on purchasing this Bluetooth® The scale will now switch to Age setting mode. After a few seconds, the LCD will show your body weight, body fat percentage, • Skin temperature can have an influence also. Measuring body fat in warm, humid Bone mass – what is it? Before Using Scale body water percentage, BMI, bone mass and muscle mass percentage for several weather when skin is moist will yield a different result than if skin is cold and dry. Bone is a living, growing tissue. During youth, your body makes new bone tissue connected Weight Watchers Scales by Conair™ Age will flash. Press the UP or DOWN button to choose the seconds, and then turn off automatically. • As with weight, when your goal is to change body composition, it is better to track faster than it breaks down older bone. In young adulthood, bone mass is at its peak; Precautions for Use Body Analysis Monitor! age (10 to 100). Pressing and holding the UP or DOWN button trends over time than to use individual daily results. after that, bone loss starts to outpace bone growth, and bone mass decreases. CAUTION! Use of this device by persons with any electrical implant such will advance numbers quickly. Press the SET button to confirm • Results may not be accurate for persons under the age of 16, or persons with an But it’s a long and very slow process that can be slowed down even more through It is designed to work with the free Weight Watchers Scales by as a heart pacemaker, or by pregnant women, is not recommended. -

Roadside Safety Design and Devices International Workshop

TRANSPORTATION RESEARCH Number E-C172 February 2013 Roadside Safety Design and Devices International Workshop July 17, 2012 Milan, Italy TRANSPORTATION RESEARCH BOARD 2013 EXECUTIVE COMMITTEE OFFICERS Chair: Deborah H. Butler, Executive Vice President, Planning, and CIO, Norfolk Southern Corporation, Norfolk, Virginia Vice Chair: Kirk T. Steudle, Director, Michigan Department of Transportation, Lansing Division Chair for NRC Oversight: Susan Hanson, Distinguished University Professor Emerita, School of Geography, Clark University, Worcester, Massachusetts Executive Director: Robert E. Skinner, Jr., Transportation Research Board TRANSPORTATION RESEARCH BOARD 2012–2013 TECHNICAL ACTIVITIES COUNCIL Chair: Katherine F. Turnbull, Executive Associate Director, Texas A&M Transportation Institute, Texas A&M University System, College Station Technical Activities Director: Mark R. Norman, Transportation Research Board Paul Carlson, Research Engineer, Texas A&M Transportation Institute, Texas A&M University System, College Station, Operations and Maintenance Group Chair Thomas J. Kazmierowski, Manager, Materials Engineering and Research Office, Ontario Ministry of Transportation, Toronto, Canada, Design and Construction Group Chair Ronald R. Knipling, Principal, safetyforthelonghaul.com, Arlington, Virginia, System Users Group Chair Mark S. Kross, Consultant, Jefferson City, Missouri, Planning and Environment Group Chair Joung Ho Lee, Associate Director for Finance and Business Development, American Association of State Highway and Transportation -

BASIC BODY COMPOSITION SCALE GET STARTED: Greatergoods.Com

BASIC BODY COMPOSITION SCALE GET STARTED: greatergoods.com/0391 CUSTOMER SUPPORT Email: [email protected] Phone: (866) 991-8494 Website: greatergoods.com Table of Contents Important Safety Notes 2 Introduction 3 Scale Description 4 Physical Features Measuring Units Setting the Measuring Unit Display Things To Know Before Using Your Scale 5 Measuring Auto-On Auto-Detection Press-Awake User Setup 6 Reading Your Results 7 For Best Results Typical Results 8 Body fat Water weight Muscle mass Bone density Troubleshooting 9 Cleaning, Maintenance, and Disposal 10 Technical Specifications 11 Manufacturer’s Warranty 13 1 Important Safety Notes Warnings • Never use, or allow others to use this unit in combination with the following medical electronic devices: • Medical electronic implants such as pacemakers • Electronic life support systems such as an artificial heart/lung • Portable electronic medical devices such as an electrocardiograph • This scale passes a harmless and unnoticeable electrical current through your body when taking a measurement. This electrical current is not felt while using the scale. This unit may cause the above mentioned medical devices to malfunction. • This product is not intended for use by pregnant women. • This product is not intended for use by infants, toddlers, and children under 10 years of age. • Do not step on the edge of the scale while getting on or off, otherwise it may tip. • Do not jump on scale. • Protect scale from hard knocks, temperature fluctuations and heat sources that are too close (e.g. Stoves, heating units). • Do not drop scale or drop any objects on it as this may damage the sensors. -

Classic Rock/ Metal/ Blues

CLASSIC ROCK/ METAL/ BLUES Caught Up In You- .38 Special Girls Got Rhythm- AC/DC You Shook Me All Night Long- AC/DC Angel- Aerosmith Rag Doll- Aerosmith Walk This Way- Aerosmith What It Takes- Aerosmith Blue Sky- The Allman Brothers Band Melissa- The Allman Brothers Band Midnight Rider- The Allman Brothers Band One Way Out- The Allman Brothers Band Ramblin’ Man- The Allman Brothers Band Seven Turns- The Allman Brothers Band Soulshine- The Allman Brothers Band House Of The Rising Sun- The Animals Takin’ Care Of Business- Bachman-Turner Overdive You Ain’t Seen Nothing Yet- Bachman-Turner Overdrive Feel Like Makin’ Love- Bad Company Shooting Star- Bad Company Up On Cripple Creek- The Band The Weight- The Band All My Loving- The Beatles All You Need Is Love- The Beatles Blackbird- The Beatles Eight Days A Week- The Beatles A Hard Day’s Night- The Beatles Hello, Goodbye- The Beatles Here Comes The Sun- The Beatles Hey Jude- The Beatles In My Life- The Beatles I Will- Beatles Let It Be- The Beatles Norwegian Wood (This Bird Has Flown)- The Beatles Ob-La-Di, Ob-La-Da- The Beatles Oh! Darling- The Beatles Rocky Raccoon- The Beatles She Loves You- The Beatles Something- The Beatles CLASSIC ROCK/ METAL/ BLUES Ticket To Ride- The Beatles Tomorrow Never Knows- The Beatles We Can Work It Out- The Beatles When I’m Sixty-Four- The Beatles While My Guitar Gently Weeps- The Beatles With A Little Help From My Friends- The Beatles You’ve Got To Hide Your Love Away- The Beatles Johnny B. -

Your Dog's Nutritional Needs

37491_Dog_P01_16 07/24/06 4:47 PM Page 1 YOUR DOG’S NUTRITIONAL NEEDS A Science-Based Guide For Pet Owners 37491_Dog_P01_16 07/24/06 4:47 PM Page 2 THE DIGESTIVE TRACT Point of Departure Storage and Processing The mechanical breakdown of food The stomach acts as a temporary storage and processing begins in the mouth, where food is facility before emptying its contents into the small intestine. ingested, chewed, and swallowed. Early stages of digestion take place in the stomach where pepsin and lipase aid in digesting protein and fat. stomach spleen esophagus colon Automatic Transport The esophagus is a short, small intestine muscular tube in which involuntary, wavelike con- tractions and relaxations liver propel food from the mouth to the stomach. Treatment Facilities In the small intestine, enzymes break down large, complex food molecules End of the Line into simpler units that can be absorbed into the bloodstream. The pan- The primary function of the large creas is an organ that does double duty, secreting digestive enzymes into intestine is to absorb electrolytes the gut and hormones, including insulin and glucogon, into the blood. and water. Also, this is where Important for fat metabolism, the liver produces bile and partially stores it microbes ferment nutrients that in the gall bladder between meals. have so far escaped digestion and absorption. COMMITTEE ON NUTRIENT REQUIREMENTS OF DOGS AND CATS DONALD C. BEITZ, Chair, Iowa State University JOHN E. BAUER, Texas A&M University KEITH C. BEHNKE, Kansas State University DAVID A. DZANIS, Dzanis Consulting & Collaborations GEORGE C. FAHEY, University Of Illinois RICHARD C. -

Artist Song Weird Al Yankovic My Own Eyes .38 Special Caught up in You .38 Special Hold on Loosely 3 Doors Down Here Without

Artist Song Weird Al Yankovic My Own Eyes .38 Special Caught Up in You .38 Special Hold On Loosely 3 Doors Down Here Without You 3 Doors Down It's Not My Time 3 Doors Down Kryptonite 3 Doors Down When I'm Gone 3 Doors Down When You're Young 30 Seconds to Mars Attack 30 Seconds to Mars Closer to the Edge 30 Seconds to Mars The Kill 30 Seconds to Mars Kings and Queens 30 Seconds to Mars This is War 311 Amber 311 Beautiful Disaster 311 Down 4 Non Blondes What's Up? 5 Seconds of Summer She Looks So Perfect The 88 Sons and Daughters a-ha Take on Me Abnormality Visions AC/DC Back in Black (Live) AC/DC Dirty Deeds Done Dirt Cheap (Live) AC/DC Fire Your Guns (Live) AC/DC For Those About to Rock (We Salute You) (Live) AC/DC Heatseeker (Live) AC/DC Hell Ain't a Bad Place to Be (Live) AC/DC Hells Bells (Live) AC/DC Highway to Hell (Live) AC/DC The Jack (Live) AC/DC Moneytalks (Live) AC/DC Shoot to Thrill (Live) AC/DC T.N.T. (Live) AC/DC Thunderstruck (Live) AC/DC Whole Lotta Rosie (Live) AC/DC You Shook Me All Night Long (Live) Ace Frehley Outer Space Ace of Base The Sign The Acro-Brats Day Late, Dollar Short The Acro-Brats Hair Trigger Aerosmith Angel Aerosmith Back in the Saddle Aerosmith Crazy Aerosmith Cryin' Aerosmith Dream On (Live) Aerosmith Dude (Looks Like a Lady) Aerosmith Eat the Rich Aerosmith I Don't Want to Miss a Thing Aerosmith Janie's Got a Gun Aerosmith Legendary Child Aerosmith Livin' On the Edge Aerosmith Love in an Elevator Aerosmith Lover Alot Aerosmith Rag Doll Aerosmith Rats in the Cellar Aerosmith Seasons of Wither Aerosmith Sweet Emotion Aerosmith Toys in the Attic Aerosmith Train Kept A Rollin' Aerosmith Walk This Way AFI Beautiful Thieves AFI End Transmission AFI Girl's Not Grey AFI The Leaving Song, Pt. -

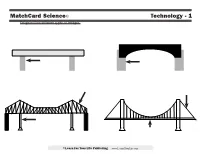

Matchcard Science© Technology - 1 Diagram Four Different Types of Bridges

MatchCard Science© Technology - 1 Diagram four different types of bridges. ©Learn For Your Life Publishing www.Learn4YourLife.com MatchCard Science© ANSWER KEY Technology - 1 Diagram four different types of bridges. BEAM ARCH Weight of the beam Weight is spread evenly pushes straight down PIERS ABATEMENTS Supports the weight of the Foundations anchored main beam firmly in the ground TRUSSES Patterned rods that strengthen the main beam CABLE CANTILEVER SUSPENSION Attached to the on any type of bridge ground beyond the Made up of sections Able to span wide and towers in order to span large high distances; often distances over waterways so ships can sail underneath CENTRAL PIER Supports the weight of one section of the bridge DECK Hangs from large cables above ©Learn For Your Life Publishing www.Learn4YourLife.com MatchCard Science© LEARNING ACTIVITIES Technology - 1 Building Bridges Arch Bridge Suspension Bridge Before looking at the Matchcard, the students To make an arch bridge you may need to raise I always thought they were called suspension can experiment with ways to build bridges to or lower the height of your bridge by changing bridges because everyone in the car was in sus- make them stronger. You will need: the number of books. pense when we crossed them. Not really. But if • A stack of books (they act as the piers) Take another index card and bend it into I had known they were called suspension bridges • Some index cards (bridge supports) an arch and set it under the beam of your beam because the entire bridge and all those cars were • Toy cars - Matchbox size is fine bridge. -

What Is a Healthy Weight?

What Is A Healthy Weight? Your weight can affect your health and the way you feel about yourself. How much you weigh mainly depends on your lifestyle and your genes. A healthy weight is a weight that does not create health or other problems for you. Many people think this means they need to be thin or skinny. But being as “skinny” as a fashion model may not be what is healthy for you. Not everyone can or should be thin. But with the right choices, everyone can be healthier. Is my weight healthy? Use the chart below to find the maximum weight that is healthy for your height. MAXIMUM HEALTHY WEIGHT CHART Height Maximum Healthy (ft, in) Weight (lb) 5’0” 125 5’1” 125 5’2” 130 5’3” 135 5’4” 140 5’5” 145 5’6” 150 5’7” 155 5’8” 160 5’9” 165 5’10” 170 5’11” 175 6’0” 180 F-1 What is Body Mass Index (BMI)? Body Mass Index (BMI) adjusts your weight for your height. The maximum healthy weights shown in the chart on page F-1 are based on BMI. The higher your BMI is, the greater your chances of heart disease, stroke, high blood pressure, diabetes, osteoarthritis, some cancers, and/or sudden death. Do I have a healthy BMI? With a calculator, it is easy to figure out your BMI. Use this simple formula (using pounds and inches). Your weight X 703 BMI = Your height X your height The example below shows the BMI for Sarah, who is 5’3” (63”) and weighs 150 pounds.