Life's First Great Crossroads.Pdf

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Kids Elect President Barack Obama the Winner in Nickelodeon's Kids Pick the President "Kids' Vote" National Poll

Kids Elect President Barack Obama The Winner In Nickelodeon's Kids Pick the President "Kids' Vote" National Poll More Than Half a Million Votes Cast NEW YORK, Oct. 22, 2012 /PRNewswire/ -- The kids of the United States have spoken and President Barack Obama has been elected the winner of Nickelodeon's 2012 Kids Pick the President "Kids' Vote." Since it began in 1988, kids have correctly picked the winner (in advance of the national election) five out of the last six times. More than half a million votes were cast in the network's online poll as part of Nickelodeon's Kids Pick the President initiative to build young citizens' awareness of, and involvement in, the election process. President Obama received 65% of the vote and former Governor Mitt Romney received 35%. In order to more closely replicate the actual election, and to ensure the results were more authentic, this year the voting was limited to one vote per electronic device. Kids were able to cast their votes online from Oct. 15 to Oct. 22. On Monday, Oct. 22, at 7:30 p.m. (ET/PT), Linda Ellerbee, the Emmy Award-winning host of Nickelodeon's Nick News, will announce the winner of the Kids Pick the President "Kids' Vote" on the network. "What politicians do definitely affects kids but for me, it's not about who wins," said Ellerbee. "It's about creating tomorrow's voters. Democracy takes work. We're the practice field." Leading up to the Kids Pick the President online vote, Nickelodeon aired two election-themed Nick News with Linda Ellerbee specials this year, which ranked as the series' highest-rated episodes for 2012 to date. -

First Lady Michelle Obama to Receive Nickelodeon's Big Help Award

First Lady Michelle Obama To Receive Nickelodeon's Big Help Award Award Kicks Off The Big Help "Millions On The Move" Pro-Social Campaign NEW YORK, March 25, 2010 /PRNewswire via COMTEX/ -- Nickelodeon will honor the First Lady of the United States, Michelle Obama, with the Big Help Award in a special presentation during Nickelodeon's 23rd Annual Kids' Choice Awards on Saturday, March 27. The Big HelpAward will pay tribute to the First Lady for her leadership in championing a healthy generation of kids and families through her recently launched Let's Move! initiative. The award recognizes those who seek to better the world, and whose significant impact on their community has inspired kids to do the same. "First Lady Michelle Obama has taken on one of this generation's most pressing concerns: the health and wellness of our nation's children," said Marva Smalls, Executive Vice President, Public Affairs and Chief of Staff, Nickelodeon/MTVN Kids and Family Group. "Her willingness to work hard, influence others and her dedication to improving the nation is inspiring, and we are proud to honor her for her commitment to empowering kids and families to address one of the most important issues of today." Launched in February 2010 by the First Lady to end the American epidemic of childhood obesity in a single generation, the nationwide Let's Move! campaign focuses on helping parents make healthier life choices for their families, providing healthier food in schools, encouraging kids to be more active and ensuring access to healthy, affordable food in every part of the country. -

H1 2019 Trends and Opportunities What’S Trending in Social TV: H1 2019

What’s Trending In Social TV H1 2019 Trends and Opportunities What’s Trending In Social TV: H1 2019 The state of social media for TV has been strong so far in 2019. Total Fan Growth for TV pages across Facebook, Twitter and Instagram is up 29% in the first half of 2019 compared to the second half of 2018, while social engagement increased 15% during the same time period. For Facebook, that largely means TV pages continue to recover from the algorithm changes in early 2018 that significantly limited organic reach. As TV focuses on strengthening engagement with their fanbase as opposed to just growing it, Facebook response rate and video views were up in the first half of 2019, inching back to pre-algorithm change levels. It’s a similar story for Twitter, where the TV space needed to alter their strategies following a mid-2018 purge of fake and dormant users. While the volume of tweets from TV accounts was down in the first half of 2019, the “less is more” strategy has been paying off. In Q2 2019, the average number of video views for TV hit its highest peak since the beginning of 2017. Meanwhile, the success of Instagram Stories is something TV Pages are taking advantage of in 2019. The volume of Instagram Stories published by TV accounts increased by 176% comparing Q2 2019 to Q1 2018. TV has also seen substantial growth on YouTube halfway through 2019, with fan counts and video views on the platform up 45% and 28% respectively, comparing H1 2019 to H1 2018. -

2003 Calendar

Marva Smalls arva Smalls is Executive Vice President, Public Affairs and Chief of Staff of Nickelodeon, the #1 kids’ entertainment brand, TV Land, the highest M rated cable network to launch within the past five years, and TNN, which has been newly repositioned as The National Network. In her Public Affairs role, Smalls oversees Nickelodeon’s pro-social and corporate responsibility initiatives and the company’s relationships with child advocates, government officials, educators, and nonprofit organizations. She also spearheads The Big Help, Nickelodeon’s award-winning national campaign that in eight years has encouraged and empowered kids to pledge more than 100 million hours of volunteer service to their communities. As Chief of Staff, Smalls is the chief administrative officer for all three networks and their ancillary businesses, coordinating and directing financial resources, personnel, and facilities for their New York, Los Angeles, Orlando, and international offices. Smalls also manages and oversees meetings of the company’s Executive Team, a strategic planning group comprising the senior executives in charge of each network and line of business. Honored with the prestigious George C. Peabody and Golden CableAce awards, The Big Help’s grassroots efforts have given more than 40 million kids the tools and motivation to connect to their communities and make a difference in their world. The campaign has been recognized for its achievements by both the Clinton and Bush administrations and has garnered the support of the top names in the entertainment industry, from Mariah Carey and Whoopi Goldberg to Britney Spears. Under Smalls, The Big Help has become universally recognized among kids in the U.S. -

Marva Smalls

MARVA SMALLS Executive Vice President of Global Inclusion Strategy, MTV Networks & Executive Vice President of Public Affairs, and Chief of Staff Nickelodeon / MTVN Kids & Family Group Marva Smalls is Executive Vice President (EVP) of Public Affairs, Chief of Staff for Nickelodeon/MTVN Kids & Family Group and EVP of Global Inclusion Strategy, MTV Networks. As EVP of Global Inclusion Strategy, Smalls works with the leadership of all MTVN brands to champion multiculturalism, inclusiveness and diversity across the company worldwide, and the development of the next generation of leaders across MTV Networks’ worldwide brands. She also works to expand MTV Networks’ partnerships with leading external organizations. Smalls serves as a member of MTV Networks’ senior strategy team led by Judy McGrath, Chairman and CEO of MTV Networks. As Chief of Staff for Nickelodeon/MTVN Kids and Family Group, Smalls is the chief administrative officer for the networks and their ancillary businesses, coordinating and directing financial resources, personnel and facilities for their New York, Los Angeles and international offices. Smalls also manages and oversees meetings of the company’s Executive Management Team, a strategic planning group comprised of the senior executives in charge of each network and line of business. An established veteran in the public sector, Smalls also oversees all of the pro-social and corporate responsibility initiatives for Nickelodeon/MTVN Kids and Family Group and its relationships with advocates, government officials, educators, non-profit organizations and trade associations. Smalls has longstanding relationships with public affairs, government relations, communications and philanthropic organizations on both the state and national level. Smalls has been a leader in developing strategies to combat the growing obesity epidemic with kids. -

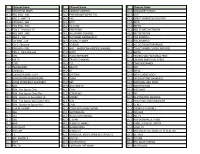

Channel Name # Channel Name # Channel Name 10.2 SPECTRUM

# Channel Name # Channel Name # Channel Name 10.2 SPECTRUM NEWS 34.1 COMEDY CENTRAL 46.2 DISCOVERY FAMILY 11.1 ABC (HD) - ABC 34.2 PARAMOUNT (SPIKE TV) 46.3 CMT 11.2 ABC 2 - GRIT TV 34.3 VH1 47.1 GREAT AMERICAN COUNTRY 11.6 CBS (HD) - CBS 35.1 MTV 47.2 ESPN 12.1 FOX (HD) - FOX 35.2 TV LAND 47.3 ESPN2 12.2 FOX 2 - Antenna TV 35.3 FREEFORM 48.2 NBC SPORTS NETWORK 12.6 NBC (HD) - NBC 36.1 HALLMARK CHANNEL 48.3 SEC NETWORK 12.7 NBC 2 - TJN 36.2 NATIONAL GEOGRAPHIC 49.1 FOX SPORTS 1 13.1 CW (HD) - CW 36.3 ANIMAL PLANET 49.2 FOX SPORTS 2 13.2 CW 2 - Bounce 37.1 SCIENCE 49.3 VELOCITY(MOTORTREND) 13.6 PBS (HD) - PBS 37.2 AHC – AMERICAN HEROES CHANNEL 50.1 TCM (TURNER CLASSIC MOVIES) 13.7 PBS 2 - Ohio Channel 37.3 HGTV 50.3 EWTN 23.1 ION 38.1 FOOD NETWORK 51.1 TELEMUNDO NATIONAL FEED 23.2 ME TV 38.2 TRAVEL CHANNEL 25.1 UNIMAS (NATIONAL FEED) 24.1 COZI 38.3 TLC 51.3 CNN EN ESPANOL 24.3 TELEMUNDO 39.1 BRAVO 52.1 FXX 25.1 UNIMAS L 39.2 E! 52.2 MTV2 25.2 UNIVISION (HD) - UNV 39.3 LIFETIME 52.3 MTV CLASSIC ROCK 25.3 HOMESHOPPINGNETWORK 40.1 OWN 53.1 UP (UPLIFTING CHANNEL) 26.1 EVINE (FORMERLY SHOPNBC) 40.2 BET 53.2 NATIONAL GEO WILD 26.2 QVC 40.3 OVATION TV 53.3 SMITHSONIAN 28.1 RSN - Fox Sports Ohio 41.1 CNN 54.1 VICELAND 28.2 RSN - Fox Sports Ohio Plus 41.2 FOX NEWS 54.2 FYI 28.3 RSN - Spectrum SportsNet LA 41.3 MSNBC 54.3 DESTINATION AMERICA 29.1 RSN - Fox Sports Sportstime Ohio 42.1 HLN 55.1 INVESTIGATION DISCOVERY 29.2 RSN - Spectrum Sports Net 42.2 CNBC 55.2 EL REY 30.2 USA NETWORK 42.3 FOX BUSINESS NETWORK 55.3 COOKING CHANNEL 30.3 A&E 43.1 BLOOMBERG -

Download the Program

Sponsors Partners Special Thanks The Alliance for Children and Television (ACT) would like to warmly thank it’s Média-Jeunes 2010 advisory committee : Guillaume Aniorté Pierre Proulx Tribal Nova Alliance Numérique Marie-Claude Beauchamp Nancy Savard CarpeDiem Productions 10e Ave Marie-Hélène Guay Sylvie Tremblay Télé-Québec Productions Sovimage Marc Beaudet Turbulent Special thanks go to Louise Lantagne and Lisa Savard of Radio-Canada for housing the Alliance for Children and Television’s Offi ce free of charge. Special thanks as well to Kirsten Schneid, Organization Manager of the Munich PRIX JEUNESSE and to David W. Kleeman, Executive Director, American Center for Children and Media, for helping us with the screening of the Munich Prix Jeunesse. Many thanks to all our collaborators and volunteers. Summary Welcome note from ACT’s Director 3 Organization 4 A word from our Sponsors 5 Schedule – Conferences, November 18 9 The future of Quebec’s youth animation industry 10 How can we convey positive messages to young people through the various media platforms they use? 13 Exclusive Lunch with a Broadcaster 15 Is TV really dying? 16 Portrait of the Situation with the new CMF 18 Audience migration to new platforms: what are the challenges for public broadcasters? 19 Engaging kids and building communities around a TV brand 21 Schedule – Screenings, November 19 23 Welcome note from ACT’s Director Welcome to Média-Jeunes 2010! Here we are – creators, artists, producers, broadcasters, researchers and fi nancial backers – all together again to review our methods, expand our horizons, and discuss the latest issues. This year, we’re also taking the opportunity to unveil our new name, logo and mission statement! We are now in a world where content is increasingly delivered on new platforms, especially where kids are concerned, so the Alliance is giving itself a makeover to expand its efforts to all types of screens, not just TV. -

Nickelodeon's Eighth Annual Worldwide Day of Play to Combine

Nickelodeon's Eighth Annual Worldwide Day of Play to Combine With First Lady Michelle Obama's "Let's Move" Campaign and The President's Council on Fitness, Sports and Nutrition in Its Biggest Celebration of Play Ever, Live From Washington, D.C.'s Ellipse First Lady Featured in Exclusive Event PSA Debuting on Sept. 3 NEW YORK, Sept. 1, 2011 /PRNewswire via COMTEX/ -- Nickelodeon is joining with the First Lady's "Let's Move" campaign and the President's Council on Fitness, Sports and Nutrition to bring for the first time its flagship Worldwide Day of Play (WWDOP) event to the Ellipse in Washington, D.C., for the biggest celebration of active play in the eight-year history of the initiative. On Saturday, Sept. 24, Nickelodeon and its partners will host an entire day of activities and games for kids and their families to encourage active and healthy lifestyles. Additionally, as it has for the past seven years, Nickelodeon's networks and websites will go dark from 12 to 3 p.m. (all times ET/PT) as a signal to kids and families to get up and get active. "Kids need to get moving every day to grow up healthy and strong," said First Lady Michelle Obama. "Whether it's hoola hooping, kicking around a soccer ball or - yes - double dutching, playing is the perfect way to keep active, stay healthy and have fun." "First Lady Michelle Obama and the President's Council have shown admirable leadership in raising awareness about the importance of kids and families living healthier and more active lifestyles," added Marva Smalls, Executive Vice President, Public Affairs, Nickelodeon. -

Learn the BEST HOPPER FEATURES

FEATURES GUIDE Learn The 15 BEST HOPPER TIPS YOU’LL FEATURES LOVE! In Just Minutes! Find A Channel Number Fast Watch DISH Anywhere! (And You Don’t Even Have To Be Home) Record Your Entire Primetime Lineup We’ll Show You How Brought to you by 1 YOUR REMOTE CONTENTS 15 TIPS YOU’LL LOVE — Pg. 4 From fi nding a lost remote, binge watching and The Hopper remote control makes it easy for you to watch, search and record more, learn all about Hopper’s best features. programming. Here’s a quick overview of the basics to get you started. Welcome HOME — Pg. 6 You’ve Made A Smart Decision MENU — Pg. 8 With Hopper. Now We’re Here SETTINGS — Pg. 10 DVR TV Power Parental Controls, Guide Settings, Closed Displays your Turns the TV To Make Sure You Understand Captioning, Screen Adjustments, Bluetooth recorded programs. on/off. All That You Can Do With It. and more. Power Guide Turns the receiver Displays the Guide. APPS — Pg. 12 on/off. Netfl ix, Game Finder, Pandora, The Weather CEO and cofounder Charlie Ergen remembers Channel and more. the beginnings of DISH as if it were yesterday. DVR — Pg. 14 The Tennessee native was hauling one of those Operating your DVR, recording series and Home Search enormous C-band TV dish antennas in a pickup managing recordings. Access the Home menu. Searches for programs. truck, along with his fellow cofounders Candy Ergen and Jim DeFranco. It was one of only two PRIMETIME ANYTIME & Apps Info/Help antennas they owned in the early 1980s. -

Warhorse: Teacher Resource Guide

Teacher Resource Guide WarHorseWH Title :Page1.12.12_H4 Teacher title Resource page.qxd 12/29/11 Guide 2:21 PM Page 1 by Heather Lester LINCOLN CENTER THEATER AT THE VIVIAN BEAUMONT under the direction of André Bishop and Bernard Gersten NATioNAL THEATRE of GREAT BRiTAiN under the direction of Nicholas Hytner and Nick Starr in association with Bob Boyett War Horse LP presents National Theatre of Great Britain production based on the novel by Michael Morpurgo adapted by Nick Stafford in association with Handspring Puppet Company with (in alphabetical order) Stephen James Anthony Alyssa Bresnahan Lute Breuer Hunter Canning Anthony Cochrane Richard Crawford Sanjit De Silva Andrew Durand Joel Reuben Ganz Ben Graney Alex Hoeffler Leah Hofmann Ben Horner Brian Lee Huynh Jeslyn Kelly Tessa Klein David Lansbury Tom Lee Jonathan Christopher MacMillan David Manis Jonathan David Martin Nat Mcintyre Andy Murray David Pegram Kate Pfaffl Jude Sandy Tommy Schrider Hannah Sloat Jack Spann Zach Villa Elliot Villar Enrico D. Wey isaac Woofter Katrina Yaukey Madeleine Rose Yen sets, costumes & drawings puppet design, fabrication and direction lighting Rae Smith Adrian Kohler with Basil Jones Paule Constable for Handspring Puppet Company director of movement and horse movement animation & projection design Toby Sedgwick 59 Productions music songmaker sound music director Adrian Sutton John Tams Christopher Shutt Greg Pliska associate puppetry director artistic associate production stage manager casting Mervyn Millar Samuel Adamson Rick Steiger Daniel Swee NT technical producer NT producer NT associate producer NT marketing Boyett Theatricals producer Katrina Gilroy Chris Harper Robin Hawkes Karl Westworth Tim Levy executive director of managing director production manager development & planning director of marketing general press agent Adam Siegel Jeff Hamlin Hattie K. -

Entire Issue (PDF)

E PL UR UM IB N U U S Congressional Record United States th of America PROCEEDINGS AND DEBATES OF THE 112 CONGRESS, FIRST SESSION Vol. 157 WASHINGTON, FRIDAY, SEPTEMBER 23, 2011 No. 143 House of Representatives The House met at 9 a.m. and was last day’s proceedings and announces active member and chaplain of the 100 called to order by the Speaker pro tem- to the House his approval thereof. Black Men of the Bay Area, Inc., and a pore (Mr. DOLD). Pursuant to clause 1, rule I, the Jour- director for the Oakland African Amer- f nal stands approved. ican Chamber of Commerce Board. He f is married to his wife, Felicia S. DESIGNATION OF THE SPEAKER Brooks-Hames, and is the proud father PRO TEMPORE PLEDGE OF ALLEGIANCE of three children. The SPEAKER pro tempore laid be- The SPEAKER pro tempore. Will the I thank Pastor Hames for his wise fore the House the following commu- gentlewoman from California (Ms. LEE) counsel, for his spiritual leadership and nication from the Speaker: come forward and lead the House in the for his commitment to making this a better world for all God’s children. WASHINGTON, DC, Pledge of Allegiance. September 23, 2011. Ms. LEE of California led the Pledge f I hereby appoint the Honorable ROBERT J. of Allegiance as follows: ANNOUNCEMENT BY THE SPEAKER DOLD to act as Speaker pro tempore on this I pledge allegiance to the Flag of the PRO TEMPORE day. United States of America, and to the Repub- JOHN A. BOEHNER, lic for which it stands, one nation under God, The SPEAKER pro tempore. -

Shine Global 10 Year Report 2005-2015

10TH ANNIVERSARY REPORT Inspire Co-Founder and Executive Director Susan MacLaury As we celebrate our 10th anniversary, it’s with a mixture of pride, happiness and some astonishment. If you, or someone you know, makes independent films you understand what I mean. Working in this medium - especially to make documentaries about children struggling against serious odds all over the world – is hard. It takes confidence, support, diligence and most of all, passion… the belief that the stories you tell CAN make a difference. And passion is one resource we have in abundance. As a former social worker and health educator I always imagined that our films would reach into classrooms around the world, and they have. Beginning with War/Dance, we have created free discussion guides and standards-based curricula for grades 7-12 for every one of our films. We added power point decks and fact sheets for university courses and finally also developed arts and media literacy workshops for community screenings as well. With the help of a recent matching grant from the National Endowment of the Arts, we’re now creating an additional outreach effort, IGNITE, to bring our films and newly designed discussion guides to as many as 150 programs serving underserved children nationally. As we begin our next 10 years we are excited to continue working independently, but will also embrace partnerships with other filmmakers. Indeed, over the years we’ve been privileged to meet dozens of talented filmmakers who, like us, believe in the power of film to transform children’s lives. We are now actively seeking partnerships with them to make short and feature-length docs, narrative films, web series, and even an animated TV series.