Tel: (44) (0) 117 9656261

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The Materials and Components for Missiles Innovation and Technology Partnership, MCM ITP Is a Dstl and DGA Sponsored Research Fu

The Materials and Components for Missiles Innovation and Technology Partnership, MCM ITP is a dstl and DGA sponsored research fund open to all UK or French companies and academic institutions. Launched in 2007, the MCM ITP develops novel, exploitable technologies for generation-after-next missile systems. The MCM ITP aims to consolidate the UK-French Complex Weapons capability, strengthen the technological base and allow better understanding of common future needs. The programme manages a portfolio of over 100 cutting-edge technologies which hold the promise of major advances, but are still at the laboratory stage today. The MCM ITP is aligned into eight technical domains, each of which is led by one of the MCM ITP industrial consortium partners1. 1 The MCM ITP Industrial Consortium partners are: MBDA; THALES; Roxel; Selex ES; Safran Microturbo; QinetiQ; Nexter Munitions. Funding The programme is funded equally by the governments and the industrial partners and is composed of research projects on innovative and exploratory technologies and techniques for future missiles. There is strong participation from SMEs and academia with 76 participating in the programme to date, and a total of 121 organisations involved in the overall programme. With an annual budget of up to 12.5M€ and 30% of the budget targeted towards SMEs and Academia, the MCM has become the cornerstone of future collaborative research and technology demonstration programmes for UK-French missile systems. Conference On 21st and 22nd October 2015, DGA, dstl, MBDA and its partners will review the last two years of the MCM ITP programme, and present the technical advances that have been made possible thanks to this cooperative programme. -

MBDA UK CSR for 2018

CORPORATE & SOCIAL RESPONSIBILITY REPORT 2018 CONTENTS Our business overview This is MBDA’s tenth annual Corporate and CEO statement 04 Social Responsibility Report covering the calendar year 2018. Executive summary 05 Copyright statement Who we are 06 This document and the information contained Our Vision, Mission, Strategy & Values 07 herein is proprietary information of MBDA and shall not be disclosed or reproduced without the prior authorisation of MBDA UK Limited. © Copyright MBDA UK Limited 2019. ‘MBDA’ in the context of this document is Our main report defined as: MBDA France, MBDA UK, MBDA Our corporate and social focus – six principal domains 09 Italia, MBDA Deutschland, MBDA España and MBDA Inc. all forming MBDA. Providing assurance to our customers and shareholders 10 Report compiled and edited by Group Directorate Business Ethics and Corporate Responsible business 23 Responsibility. Please send questions by email to: Business ethics 27 [email protected] Company giving and community engagement 31 Our people 37 Environmentally responsive 45 Appendix 49 Antoine Bouvier, CEO As a multinational company operating in many different domains, Corporate and Social Responsibility (CSR) continues to be an intrinsic Excellence at your side part of our business. During 2018, working under the umbrella of our CSR framework initiatives, we MBDA’s drive towards operational excellence “ has been fundamental in establishing the future made excellent progress through our continued commitment to our employees, our customers and model of European cooperation, in developing the communities within which we operate. new customer partnerships to ensure sovereign capabilities and in providing the accessible At the heart of our company are our employees, global market with leading guided weapon who work in skilled teams to deliver our systems solutions. -

Company General Use

TEMPEST: IMPORTANTE PASSO AVANTI NELLA COLLABORAZIONE INDUSTRIALE INTERNAZIONALE PER LO SVILUPPO DELLE FUTURE CAPACITA’ DI COMBATTIMENTO AEREO 22 luglio 2020 – Regno Unito, Svezia e Italia hanno avviato un dialogo industriale volto a rafforzare la loro collaborazione per lo sviluppo del futuro sistema di combattimento aereo di nuova generazione. Nel nuovo framework trilaterale le industrie delle nazioni coinvolte apporteranno le proprie capacità e competenze nel settore Combat Air per collaborare alla ricerca e allo sviluppo di tecnologie all'avanguardia. Le tre industrie nazionali comprendono le principali società di difesa di Regno Unito (BAE Systems, Leonardo UK, Rolls Royce e MBDA UK), Italia (Leonardo Italia, Elettronica, Avio Aero e MBDA Italia) e Svezia (Saab e GKN Aerospace Sweden). L’annuncio odierno prende le mosse dai dialoghi bilaterali già avviati tra le industrie di Regno Unito, Svezia e Italia dando vita, a patire da oggi, a un vero e proprio gruppo di lavoro industriale trilaterale. Le aziende valuteranno insieme le iniziative da intraprendere per lo sviluppo delle future capacità nel combattimento aereo sfruttando know-how, competenze e sviluppi tecnologici dei sistemi di difesa aerea attualmente esistenti e futuri. L’intesa di oggi è un passo avanti nel percorso verso l’accordo tra le industrie nazionali per la formalizzazione di aree di collaborazione congiunta sullo sviluppo del futuro sistema di combattimento aereo. Come parte di un settore di grande successo internazionale come la difesa aerea, queste aziende impiegano in tale campo decine di migliaia di persone sviluppando, al contempo, un considerevole numero di posti di lavoro altamente qualificato attraverso il proprio indotto, sostenendo inoltre la sicurezza nazionale e la prosperità economica nel Regno Unito, in Svezia e in Italia. -

Press Release

Press release 16 June 2009 MBDA CO-ORDINATING FRANCO-BRITISH MISSILE RESEARCH In a few days, an innovative approach to defence equipment research will be delivering its first results. MBDA, at the heart of a partnership bringing together French and UK efforts in the field of missiles, is co-ordinating a team that includes large businesses, SMEs, laboratories and universities. The Innovation and Technology Partnership on Materials and Components for Missiles (MCM ITP) is being performed under a Technical Arrangement between French Delegation Generale pour l’Armement (DGA) and UK Ministry of Defence (MOD) to optimise missile research activities. The sharing of the results from within the research themes of this sensitive defence sector will be presented at the MCM ITP (Materials and Components for Missiles – Innovation & Technology Partnership) conference which will take place at the Grand Palais in Lille (in the north of France) on 22nd and 23rd June 2009. For the first time, two countries are sharing advanced research results as well as their aspirations for technology breakthroughs in subject areas such as: co-operative guidance of multiple missiles; miniaturised active antennae based on MEMS (Micro-Electro-Mechanical Systems) technology; UV fluorescence for target discrimination ; dual mode seekers ; thrust modulation in rocket motors; modular effect warheads and intelligent materials allowing for morphing, namely the continuous deformation of aerodynamic control surfaces. In December 2007, MBDA, Europe’s missile systems champion, was awarded a three- year contract (extendable to five years) to carry out the first ITP partnership between France and the UK. With an annual budget of 14 million euros, this programme brings together the missile industry of the two countries, and notably, the SMEs, universities and state laboratories. -

Day Time Activity RR / Participants Mon 20 09:00

Day Time Activity RR / participants Mon 20 09:00 – FIA Connect: Opening Ceremony Moderated by: 10.25 Introduction – Gareth Rogers, Chief Executive, Farnborough International Peggy Hollinger, International Business Editor, Financial Times Senior Industry Leaders Panel This headline event will bring together senior international aerospace and Speakers: defence leaders to discuss their perspectives on the outlook for industry. Gareth Rogers. Chief Executive Officer. Farnborough International. Victoria Foy. Executive Vice President. Safran Seat GB. Tony Wood. CEO. Meggitt. Dr Charles Woodburn. Group Chief Executive Officer. BAE Systems plc. Jacqui Sutton. Chief Customer Officer - Civil Aerospace. Rolls-Royce Guillaume Faury. CEO. Airbus. Alessandro Profumo. CEO. Leonardo. Mon 20 10.30 – Building An Integrated UK-India Partnership For India’s Future Aerospace & Speakers: 11.30 Defence Platforms The UK India Business Council’s Aerospace & Defence Industry Group and ADS Kishore Jayaraman, President South Asia, Rolls- are organising a virtual panel discussion to discuss how to build an integrated Royce UK-India partnership for India’s future aerospace & defence platforms. George Kyriakides, Director of International Industrial Cooperation, MBDA This event will discuss and explore, in practical terms, how to create that Nik Khanna, Managing Director, India, BAE alliance: including subjects like sharing technology, building innovation, Systems opportunities, challenges, and models for genuine collaboration. The topic S Rangarajan, CEO of Data Patterns aligns well with a G2G strategic relationship recently enhanced by the April Ian Draper, Industrial Capacity Lead, DSO 2019 Defence Equipment Collaboration MoU between India and the UK. A small, high-level panel, which will include two platform providers (BAE Systems and Rolls-Royce), UK and Indian systems providers (MBDA and Data Patterns), as well as senior representation from the UK and Indian Governments (DRDO). -

Airshow News PUBLICATIONS

DAY 2 FARNBOROUGH July 17, 2018 Airshow News PUBLICATIONS ADVERTISEMENT MISSILE DEFENSE ADVERTISEMENT 18RTN2651_Raytheon_AIN Cover.indd 1 6/28/18 4:27 PM MISSILE DEFENSE CONNECTING VISION WITH PRECISION Across all tiers, enabling all missions, prepared for all threats — Raytheon Missile Defense solutions are ready now to defend warfi ghters and safeguard nations. Raytheon combines vision, precision and partnership to deliver for customers and drive success. PATRIOT TM SM-3® SM-6® NASAMSTM 3,200+ tests. 1,500 fl ight With nearly 30 space intercepts, Standard Missile-6 delivers A joint Raytheon-Kongsberg tests. 200+ combat uses by Standard Missile-3 is the a proven over-the-horizon product, the National fi ve partner nations. Patriot’s world’s only ballistic missile offensive and defensive Advanced Surface-to-Air combat-proven, cost-saving interceptor deployable from capability. It’s the only missile Missile System (NASAMS) is technology is used by 15 land or sea. Its versatility that supports anti-air warfare, a highly adaptable mid-range countries to drive international makes it invaluable to upper- anti-surface warfare and sea- solution for any operational air and missile defense. As tier missile defense for the based terminal ballistic missile air defense requirement. The threats evolve, so does Patriot, U.S. and its allies. When it is defense in one solution — tailorable, state-of-the-art with advanced capabilities land-based in Poland, SM-3 and it’s enabling the U.S. and defense system can quickly perfectly engineered for today’s will defend all of Europe its allies to cost-effectively identify, engage and destroy and tomorrow’s challenges. -

SELLING to the Mod

S2MoD_Edition 16 17/9/08 4:51 pm Page 1 SELLING TO THE MoD EDITION 16 S2MoD_Edition 16 17/9/08 3:13 pm Page 2 Defense Contracts International DCI Delivering Precision Intelligence Leading the way in global defense contract opportunities and market intelligence The new, dynamic and improved Defense Contracts International (DCI) service has arrived! Subscribe to the new and improved Defense Contracts International service today and gain access to the global defense marketplace and the market intelligence you need to win new national and international business as well as a unique leading edge over your competitors. One-month FREE trial available Defense Contracts International My DCI My DCI allows you to effectively SAVE £200 manage all your contract opportunities, meaning you prioritise on your first year those which are most important and of subscription avoid missing vital deadlines (second year price £960 plus VAT) As a DCI subscriber you will also have access to a brand-new ‘My DCI’ area where you can benefit Including: from exciting new features, including: Viewing and analysing statistics on contracts Daily Email Contract Alert service with a returned in your Daily Email Contract Alert new and improved dynamic format Flagging contract opportunities and market Unique Contracts Online search facility allowing you to search intelligence that is of particular interest to you for defense contracts 24 hours a day, seven days a week Saving time by storing specific searches Market Monitor intelligence service Accessing and viewing previous -

Major Projects Report 2015 and the Equipment Plan 2015 to 2025

Report by the Comptroller and Auditor General Ministry of Defence Major Projects Report 2015 and the Equipment Plan 2015 to 2025 Appendices and project summary sheets HC 488-II SESSION 2015-16 22 OCTOBER 2015 Our vision is to help the nation spend wisely. Our public audit perspective helps Parliament hold government to account and improve public services. The National Audit Office scrutinises public spending for Parliament and is independent of government. The Comptroller and Auditor General (C&AG), Sir Amyas Morse KCB, is an Officer of the House of Commons and leads the NAO, which employs some 810 people. The C&AG certifies the accounts of all government departments and many other public sector bodies. He has statutory authority to examine and report to Parliament on whether departments and the bodies they fund have used their resources efficiently, effectively, and with economy. Our studies evaluate the value for money of public spending, nationally and locally. Our recommendations and reports on good practice help government improve public services, and our work led to audited savings of £1.15 billion in 2014. Ministry of Defence Major Projects Report 2015 and the Equipment Plan 2015 to 2025 Appendices and project summary sheets Report by the Comptroller and Auditor General Ordered by the House of Commons to be printed on 22 October 2015 This report has been prepared under Section 6 of the National Audit Act 1983 for presentation to the House of Commons in accordance with Section 9 of the Act Sir Amyas Morse KCB Comptroller and Auditor General National Audit Office 20 October 2015 This volume has been published alongside a first volume comprising of – Ministry of Defence: Major Projects Report 2015 and the Equipment Plan 2015 to 2024 HC 488-I HC 488-II | £10.00 © National Audit Office 2015 The material featured in this document is subject to National Audit Office (NAO) copyright. -

Modernise Build Invest Who We Are Qinetiq Is a Leading Science and Engineering Company Operating Primarily in the Defence, Security and Aerospace Markets

QinetiQ Group plc QinetiQ Group plc Annual Report and Accounts 2017 Annual Report and Accounts 2017 Modernise Build Invest Who we are QinetiQ is a leading science and engineering company operating primarily in the defence, security and aerospace markets. We work in partnership with our customers to solve real-world problems through innovative solutions, delivering operational and competitive advantage. FY17^ Summary Financial Orders Revenue £ m £ m 2016:675.3 £659.8m 2016:783.1 £755.7m Underlying earnings per share* Basic earnings per share p p 18.12016: 16.3p 21.52016: 18.1p Non-financial Customer satisfaction (score out of 10) Employee engagement (score out of 1,000) 8.22016: 8.1 5962016: 623 Operational highlights LTPA contract amendment Acquisition of Meggitt Target Systems Signed the largest and most significant contract since privatisation Acquired Meggitt Target Systems business, which generates 90% to ensure the UK has world-class competitive air ranges and training of its revenue outside the UK, to support our international growth. for test pilots and aircrew. The front cover image shows the launch of a Banshee Jet 40 in the desert in Kuwait. This target was used for tracking and live firing. £ bn Customers in Value1 of contract amendment over 40 countries * Alternative performance measures ^ Year references (FY17, FY16, 2017, 2016) refer to the year ending 31 March. Alternative performance measures are used to supplement the statutory figures. These are additional key financial indicators used by management internally to assess the underlying performance of the Group. Definitions can be found in the glossary on page 151. -

MAA Approved Organizations

UK Military Aviation Authority Approved Organizations Version: 20210927-MAA_Approved_Organizations_Publishing.xlsx This document lists all Approved Organizations that are part of: Air Traffic Management Equipment Approved Organization Scheme, Contrator Flying Approved Organization Scheme, Design Approved Organization Scheme, Maintenance Approved Organization Scheme Name Full Name Locations Scope Cert Latest No Sched Latest No Scheme All Platforms Aquila is the service provider for Marshall which is divided into three areas: Marshall Technical UK.MAA.AAOS.0013 Aquila Air Traffic Management Services Ltd Fareham Services, Marshall Air traffic control service and Temporary Technical Services. 0 5 AAOS No Aircraft Queen Elizabeth Class - Combat Management System - CMS 1 (QEC Variant) / Air Traffic Control. Queen Elizabeth Class - Shared Infrastructure - Version 3. Queen Elizabeth Class / Type 45 - METOC. UK.MAA.AAOS.0018 BAE Systems Surface Ships Limited (BAE Systems Naval Ships Combat Systems) New Malden 0 0 AAOS QE Class Carriers 2D Land Based Radars, including Watchman Air Traffic Control Radar 3D Land Based Radars, including T101 & T102 Air Defence Radars 2D Naval Radars, including RT994 Surveillance Radar 3D Naval Radars, including Sampson Multi-Function Radar, S1850M Long Range Radar, ARTISAN Medium Range Radar Type 997 UK.MAA.AAOS.0003 BAES Maritime Services (Product and Training Services) Cowes Advanced Digital Tracker (ADT) 0 3 AAOS No Aircraft UKASACS Command and Control System (UCCS) at CRC's Boulmer and Scampton. Flight Plan Dissemination -

NSPA L-8302 CAPELLEN(Luxembourg) TEL:(+352)3063(+Ext.) FAX:(+352)3063 4300 N S P a AGENCE OTAN DE SOUTIEN ET D'acquisition NATO SUPPORT and PROCUREMENT AGENCY

N S P A AGENCE OTAN DE SOUTIEN ET D'ACQUISITION NATO SUPPORT AND PROCUREMENT AGENCY List of Items Table of contents: Bidding instructions Draft Purchase order List of Items MWE20019 /LC-CC-6000829413 Page 1 of 1 NATO UNCLASSIFIED NSPA L-8302 CAPELLEN(Luxembourg) TEL:(+352)3063(+ext.) FAX:(+352)3063 4300 N S P A AGENCE OTAN DE SOUTIEN ET D'ACQUISITION NATO SUPPORT AND PROCUREMENT AGENCY List of Items Line Stock Number Unit of Quantity item Description Issue 10 5360996656153 each 25 SPRING,HELICAL,COMPRESSION REFERENCES: CAGE Code Name Part Number U1604 MARTIN-BAKER AIRCRAFT CO LTD MBEU161149 F0754 MARTIN BAKER SA MBEU161149 APPLICABILITY: AIRCRAFT NF5B2000 CONDITION: NEW, NEW SURPLUS, FROM OEM OR TRACABLE TO OEM OR WITH COC FROM OEM Quality assurance requirements: This contract shall meet the AQAP 2131 requirements (NATO Quality Assurance Requirements for Final Inspection). These requirements also apply to all sub-contractors involved in this contract. GQA HEADER: Government Quality Assurance is not required for this contract. The Contractor must provide a Certificate of Conformity (CoC). Template to be used is to be found in AQAP2070. In case the contractor is not the manufacturer, the contractor shall provide a copy of the COC received from the manufacturer. Evaluation criteria: The criteria, which NSPA will employ in selecting the successful offerer will be in the following order: a. compliance with the Terms and Conditions of the RFP, b. lowest price. Although that the lowest price will be the predominant criteria in the evaluation of the proposals, NSPA is also concerned to receive your best delivery terms. -

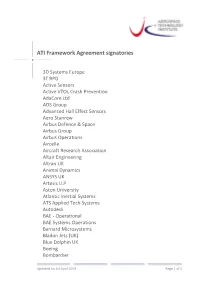

ATI Framework Agreement Signatories

ATI Framework Agreement signatories 3D Systems Europe 3T RPD Active Sensors Active VTOL Crash Prevention AdaCore Ltd ADS Group Advanced Hall Effect Sensors Aero Stanrew Airbus Defence & Space Airbus Group Airbus Operations Aircelle Aircraft Research Association Altair Engineering Altran UK Animal Dynamics ANSYS UK Artesis LLP Aston University Atlantic Inertial Systems ATS Applied Tech Systems Autodesk BAE - Operational BAE Systems Operations Barnard Microsystems Bladon Jets (UK) Blue Dolphin UK Boeing Bombardier Updated on 1st April 2019 Page 1 of 5 Bombardier Transportation UK Broetje Automation UK Callen-Lenz Associates Ltd Cambridge Aerothermal Cambridge Flow Solutions Cardiff University CCP Gransden CFMS Services Chelton Cocotec Composite Integration Composite Metal Technology Constellium UK Coventry University Cranfield University Crompton Technology Group Datum Tool and Design DeanDhawan Denis Ferranti Meters Designed Materials Deva Technologies Digital Catapult D-RisQ Dunlop Aircraft Tyres Eaton Equipmake ETher NDE Far-UK FaultlessAI Flight Refuelling Formtech Composite Future Advanced Manufacture Gas Sensing Solutions GE Aircraft Engine Services GE Aviation Systems General Dynamics Updated on 1st April 2019 Page 2 of 5 GKN Aerospace Services Glenalmond Group Goodrich Actuation Systems Goodrich Control Systems Granta Design Hamilton Sundstran Corporation Hexcel Composites Honeywell UK HS Marston Aerospace Imperial College Impression Technologies Innospec International TechneGroup Ltd Inter-Tec Solutions Ionix Advanced Technologies