Myanmar Bronzes and the Dian Cultures of Yunnan

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Chapter 5 Sinicization and Indigenization: the Emergence of the Yunnanese

Between Winds and Clouds Bin Yang Chapter 5 Sinicization and Indigenization: The Emergence of the Yunnanese Introduction As the state began sending soldiers and their families, predominantly Han Chinese, to Yunnan, 1 the Ming military presence there became part of a project of colonization. Soldiers were joined by land-hungry farmers, exiled officials, and profit-driven merchants so that, by the end of the Ming period, the Han Chinese had become the largest ethnic population in Yunnan. Dramatically changing local demography, and consequently economic and cultural patterns, this massive and diverse influx laid the foundations for the social makeup of contemporary Yunnan. The interaction of the large numbers of Han immigrants with the indigenous peoples created a 2 new hybrid society, some members of which began to identify themselves as Yunnanese (yunnanren) for the first time. Previously, there had been no such concept of unity, since the indigenous peoples differentiated themselves by ethnicity or clan and tribal affiliations. This chapter will explore the process that led to this new identity and its reciprocal impact on the concept of Chineseness. Using primary sources, I will first introduce the indigenous peoples and their social customs 3 during the Yuan and early Ming period before the massive influx of Chinese immigrants. Second, I will review the migration waves during the Ming Dynasty and examine interactions between Han Chinese and the indigenous population. The giant and far-reaching impact of Han migrations on local society, or the process of sinicization, that has drawn a lot of scholarly attention, will be further examined here; the influence of the indigenous culture on Chinese migrants—a process that has won little attention—will also be scrutinized. -

Ecological Risk Assessment of Typical Plateau Lakes

E3S Web of Conferences 267, 01028 (2021) https://doi.org/10.1051/e3sconf/202126701028 ICESCE 2021 Ecological Risk Assessment of Typical Plateau Lakes Yuyadong1.2*, Yankun2 1.School of Ecology and Environmental Science Yunnan University, China 2.The Ecological and Environmental Monitoring Station of DEEY in Kunming, China Abstract. Plateau lakes have significant ecological value. With economic development, lake pollution and ecological degradation have become increasingly prominent. There are many ecological risk assessment methods. This article combines four different ecological risk assessment methods including single-factor pollution index, geological accumulation index method, potential risk index method, and pollution load index method to analyze the heavy metal pollution in Yangzong seabed mud as comprehensively as possible. It shows that the results obtained by different ecological risk assessment methods are slightly different. The overall trends of the geological pollution index and the single-factor pollution index are similar. In terms of time, except for the two elements of mercury and cadmium, the contents of other heavy metals in 2019 are lower than in 2018, indicating that heavy metal pollution has decreased in 2019; from the perspective of spatial distribution, In 2018, the overall pollution level on the south side of Yangzonghai was higher than that in the central and northern regions of Yangzonghai . On the whole, whether it is the potential risk index or the appropriate pollution load index, the pollution level on the south side of Yangzonghai is higher than that in the central and northern areas of Yangzonghai, and the northern area has the least pollution. ecosystems is relatively reduced, which makes the economic development of plateau lake basins face severe 1 Introduction challenges. -

Social, Political and Cultural Challenges of the Brics Social, Political and Cultural Challenges of the Brics

SOCIAL, POLITICAL AND CULTURAL CHALLENGES OF THE BRICS SOCIAL, POLITICAL AND CULTURAL CHALLENGES OF THE BRICS Gustavo Lins Ribeiro Tom Dwyer Antonádia Borges Eduardo Viola (organizadores) SOCIAL, POLITICAL AND CULTURAL CHALLENGES OF THE BRICS Gustavo Lins Ribeiro Tom Dwyer Antonádia Borges Eduardo Viola (organizadores) Summary PRESENTATION Social, political and cultural challenges of the BRICS: a symposium, a debate, a book 9 Gustavo Lins Ribeiro PART ONE DEVELOPMENT AND PUBLIC POLICIES IN THE BRICSS Social sciences and the BRICS 19 Tom Dwyer Development, social justice and empowerment in contemporary India: a sociological perspective 33 K. L. Sharma India’s public policy: issues and challenges & BRICS 45 P. S. Vivek From the minority points of view: a dimension for China’s national strategy 109 Naran Bilik Liquid modernity, development trilemma and ignoledge governance: a case study of ecological crisis in SW China 121 Zhou Lei 6 • Social, political and cultural challenges of the BRICS The global position of South Africa as BRICS country 167 Freek Cronjé Development public policies, emerging contradictions and prospects in the post-apartheid South Africa 181 Sultan Khan PART TWO ContemporarY Transformations AND RE-ASSIGNMENT OF political AND cultural MEANING IN THE BRICS Political-economic changes and the production of new categories of understanding in the BRICS 207 Antonádia Borges South Africa: hopeful and fearful 217 Francis Nyamnjoh The modern politics of recognition in BRICS’ cultures and societies: a chinese case of superstition -

Changes of Water Clarity in Large Lakes and Reservoirs Across China

Remote Sensing of Environment 247 (2020) 111949 Contents lists available at ScienceDirect Remote Sensing of Environment journal homepage: www.elsevier.com/locate/rse Changes of water clarity in large lakes and reservoirs across China observed T from long-term MODIS ⁎ Shenglei Wanga,b, Junsheng Lib,c, Bing Zhangb,c, , Zhongping Leed, Evangelos Spyrakose, Lian Fengf, Chong Liug, Hongli Zhaoh, Yanhong Wub, Liping Zhug, Liming Jiai, Wei Wana, Fangfang Zhangb, Qian Shenb, Andrew N. Tylere, Xianfeng Zhanga a School of Earth and Space Sciences, Peking University, Beijing, China b Key Laboratory of Digital Earth Science, Aerospace Information Research Institute, Chinese Academy of Sciences, Beijing, China c University of Chinese Academy of Sciences, Beijing, China d School for the Environment, University of Massachusetts Boston, Boston, MA, USA e Biological and Environmental Sciences, Faculty of Natural Sciences, University of Stirling, Stirling, UK f State Environmental Protection Key Laboratory of Integrated Surface Water-Groundwater Pollution Control, School of Environmental Science and Engineering, Southern University of Science and Technology, Shenzhen, China g Key Laboratory of Tibetan Environment Changes and Land Surface Processes, Institute of Tibetan Plateau Research, Chinese Academy of Sciences, Beijing, China h China Institute of Water Resources and Hydropower Research, Beijing, China i Environmental Monitoring Central Station of Heilongjiang Province, Harbin, China ARTICLE INFO ABSTRACT Keywords: Water clarity is a well-established first-order indicator of water quality and has been used globally bywater Secchi disk depth regulators in their monitoring and management programs. Assessments of water clarity in lakes over large Lakes and reservoirs temporal and spatial scales, however, are rare, limiting our understanding of its variability and the driven forces. -

Supplement of a Systematic Examination of the Relationships Between CDOM and DOC in Inland Waters in China

Supplement of Hydrol. Earth Syst. Sci., 21, 5127–5141, 2017 https://doi.org/10.5194/hess-21-5127-2017-supplement © Author(s) 2017. This work is distributed under the Creative Commons Attribution 3.0 License. Supplement of A systematic examination of the relationships between CDOM and DOC in inland waters in China Kaishan Song et al. Correspondence to: Kaishan Song ([email protected]) The copyright of individual parts of the supplement might differ from the CC BY 3.0 License. Figure S1. Sampling location at three rivers for tracing the temporal variation of CDOM and DOC. The average widths at sampling stations are about 1020 m, 206m and 152 m for the Songhua River, Hunjiang River and Yalu River, respectively. Table S1 the sampling information for fresh and saline water lakes, the location information shows the central positions of the lakes. Res. is the abbreviation for reservoir; N, numbers of samples collected; Lat., latitude; Long., longitude; A, area; L, maximum length in kilometer; W, maximum width in kilometer. Water body type Sampling date N Lat. Long. A(km2) L (km) W (km) Fresh water lake Shitoukou Res. 2009.08.28 10 43.9319 125.7472 59 17 6 Songhua Lake 2015.04.29 8 43.6146 126.9492 185 55 6 Erlong Lake 2011.06.24 6 43.1785 124.8264 98 29 8 Xinlicheng Res. 2011.06.13 7 43.6300 125.3400 43 22 6 Yueliang Lake 2011.09.01 6 45.7250 123.8667 116 15 15 Nierji Res. 2015.09.16 8 48.6073 124.5693 436 83 26 Shankou Res. -

Yunnan: a Province Wrong Tendency in Art Opposed

Vol. 26, No. 29 July 18,'1983 BEIJIN A CHINESE WEEKLY OF EVIEW NEWS AND VIEWS II~ ~ ~. ._-~--~---~ Yunnan: A Multinational Province Wrong Tendency In Art Opposed Women Win Volleyball Tournament tures on China, so the series is resentative of the hopes and LETTERS useful to me. When people ask aspirations of the Chinese people me "What does the modernization as well as a vehicle of friendship process mean in China?" it's much for those abroad who are interest- easier to answer these questions. ed in the path the Chinese people have embarked upon. Articles on Chinese-Type. Pertti Laine Modernization Helsinki, Finland Philip T. Johnson Arlington, VA, USA Your series of articles on Chi- The series "Chinese-Type Mod- ernization" has been excellent. nese-type modernization deeply I think it safe to say that your Your articles on Chinese-type analysed the nature and charac- readers and all friends of the Chi- modernization are very interest- teristics of socialist China's mod- nese people are vitally interested ing. After reading them, I under- ernization, its emphases in con- in the modernization of Chinese stood why the leaders and the struction and plans for the future. industry, agriculture, science and masses should unite in your The articles also gave reasons why technology. Your series devoted modernization drive. However, in the gross annual value of indus- to this topic has been the most my humble opinion, if you are not trial and agricultural output can complete and cogent explanation. patient in your work, many be quadrupled towards the end defects and social problems will of the century. -

2D Hydrodynamic Modelling for Erhai Lake Applying TELEMAC Modelling System1

http://www.paper.edu.cn 2D Hydrodynamic Modelling for Erhai Lake Applying TELEMAC Modelling 1 System ZHANG Cheng* Claude GUILBAUD School of Ocean LHF Hohai University Sogreah Consultants Nanjing, P. R. China 210098 Echirolles, France 38130 [email protected] [email protected] TONG Chaofeng State Key Laboratory of Hydrology-Water Resources and Hydaulic Engineering Hohai University Nanjing, P.R.China 210098 [email protected] Abstract Numerical modelling is being used extensively to assist decision making in hydraulic and environmental field. TELEMAC System is a numerical modelling system for free surface hydrodynamics, water quality and sedimentology etc, popular in Europe but not introduced in China. The construction of 2D hydrodynamic model for Erhai Lake applies TELEMAC System for an interesting and important study. From the modeled results, lake hydrodynamics are well reproduced, the tracer’s behavior can also be seen. For the modelling itself, TELEMAC shows a good convenience and capability of reproducing reality. Keywords: numerical modelling, FEM model, TELEMAC System, Erhai Lake 1 Introduction Erhai Lake lies in the middle of Dali Prefecture, Yunnan Province, southwest China. The position is 25°16'~25°25'N, 99°32'~100°27'E. In terms of hydrology it is in the upriver part of the Lancang-Mekong River Basin which extends across 6 countries in the Southeast Asia. The Erhai Lake Basin extends across over 16 towns of Dali City and Eryuan County with a total area of 2565 square km, which accounts for 8.7% of the area of whole Prefecture. While the whole Erhai Lake surface lies in Dali city, which is the capital and political, economic and cultural centre of the Dali Prefecture. -

Lake Status Records from China: Data Base Documentation

Lake status records from China: Data Base Documentation G. Yu 1,2, S.P. Harrison 1, and B. Xue 2 1 Max Planck Institute for Biogeochemistry, Postfach 10 01 64, D-07701 Jena, Germany 2 Nanjing Institute of Geography and Limnology, Chinese Academy of Sciences. Nanjing 210008, China MPI-BGC Tech Rep 4: Yu, Harrison and Xue, 2001 ii MPI-BGC Tech Rep 4: Yu, Harrison and Xue, 2001 Table of Contents Table of Contents ............................................................................................................ iii 1. Introduction ...............................................................................................................1 1.1. Lakes as Indicators of Past Climate Changes........................................................1 1.2. Chinese Lakes as Indicators of Asian Monsoonal Climate Changes ....................1 1.3. Previous Work on Palaeohydrological Changes in China.....................................3 1.4. Data and Methods .................................................................................................6 1.4.1. The Data Set..................................................................................................6 1.4.2. Sources of Evidence for Changes in Lake Status..........................................7 1.4.3. Standardisation: Lake Status Coding ..........................................................11 1.4.4. Chronology and Dating Control..................................................................11 1.5. Structure of this Report .......................................................................................13 -

Report on the State of the Environment in China 2016

2016 The 2016 Report on the State of the Environment in China is hereby announced in accordance with the Environmental Protection Law of the People ’s Republic of China. Minister of Ministry of Environmental Protection, the People’s Republic of China May 31, 2017 2016 Summary.................................................................................................1 Atmospheric Environment....................................................................7 Freshwater Environment....................................................................17 Marine Environment...........................................................................31 Land Environment...............................................................................35 Natural and Ecological Environment.................................................36 Acoustic Environment.........................................................................41 Radiation Environment.......................................................................43 Transport and Energy.........................................................................46 Climate and Natural Disasters............................................................48 Data Sources and Explanations for Assessment ...............................52 2016 On January 18, 2016, the seminar for the studying of the spirit of the Sixth Plenary Session of the Eighteenth CPC Central Committee was opened in Party School of the CPC Central Committee, and it was oriented for leaders and cadres at provincial and ministerial -

Searchable PDF Format

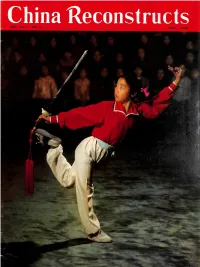

f V •.4BU. L' - •. r \ M '/ MS f tf- Ml- MA S s 1 i ... VOL. XXI NO. 6 JUNE 1972 PUBLISHED MONTHLY IN ENGLISH, FRENCH, SPANISH, ARABIC AND RUSSIAN BY THE CHINA WELFARE INSTITUTE (SOONG CHING LING, CHAIRMAN) CONTENTS EDGAR SNOW —IN MEMORIAM Soong Ching Ling 2 EDGAR SNOW (Poem) Rewi Alley 3 A TRIBUTE Ma Hai-teh {Dr. George Hatem) 4 HE SAW THE RED STAR OVER CHINA Talitha Gerlach 6 TSITSIHAR SAVES ITS FISH Lung Chiang-wen 8 A CHEMICAL PLANT FIGHTS POLLUTION 11 THE LAND OF BAMBOO 14 REPORT FROM TIBET: LINCHIH TODAY 16 HOW WE PREVENT AND TREAT OCCUPA TIONAL DISEASES 17 WHO INVENTED PAPER? 20 LANGUAGE CORNER: LOST AND FOUND 21 JADE CARVING 22 STEELWORKERS TAP HIDDEN POTENTIAL An Tung 26 WHAT I LEARNED FROM THE WORKERS AND PEASANTS Tsien Ling-hi 30 COVER PICTURES: YOUTH AMATEUR ATHLETIC SCHOOL 33 Front: Traditional sword- play by a student of wushu CHILDREN AT WUSHU 34 at the Peking Youth THEY WENT TO THE COUNTRY 37 Amateur Athletic School {see story on p. 33). GEOGRAPHY OF CHINA: LAKES 44 Inside front: Before the OUR POSTBAG 48 puppets go on stage. Back: Sanya Harbor, Hoi- nan Island. Inside back: On the Yu- Editorial Office: Wai Wen Building, Peking (37), China. shui River, Huayuan county, Cable: "CHIRECON" Peking. General Distributor: Hunan province. GUOZI SHUDIAN, P.O. Box 399, Peking, China. EDGAR SNOW-IN MEMORIAM •'V'^i»i . Chairman Mao and Edgar Snow in north Shcnsi, 1936. 'P DGAR SNOW, the life-long the river" and seek out the Chinese that today his book stands up well •*-' friend of the Chinese people, revolution in its new base. -

Supplementary Material Herzschuh Et Al., 2019 Position and Orientation Of

Supplementary Material Herzschuh et al., 2019 Position and orientation of the westerly jet determined Holocene rainfall patterns in China Nature Communications Supplementary Tables Supplementary Tab. 1 Summary statistics for canonical correspondence analyses for the whole dataset from China and Mongolia (Cao et al., 2014). Pann – annual precipitation, Mtwa – mean temperature of the warmest month; Mtco – mean temperature of the coldest month; Tann mean annual temperature, Pamjjas – precipitation between March and September, Pamjjas – precipitation between June and August. Results indicate that Pann explains most variance in the modern pollen dataset. Neither temperature nor seasonal precipitation explains more variance. Climatic variables as sole Marginal contribution based on VIF VIF predictor climatic variables Climatic 1/2 variables (without (add Explained Explained Tann) Tann) variance P-value variance P-value (%) (%) Pann 3.8 3.8 1.58 4.9 0.005 1.50 0.005 Mtco 4.3 221.7 1.36 4.2 0.005 0.67 0.005 Mtwa 1.5 116.6 0.61 2.7 0.005 1.30 0.005 Tann - 520.4 - - - - Pamjjas - - 1.50 4.9 0.005 Pjja - - 1.30 4.4 0.005 Cao, X., Herzschuh, U., Telford, R.J., Ni, J. A modern pollen-climate dataset from China and Mongolia: assessing its potential for climate reconstruction. Review of Palaeobotany and Palynology 211, 87-96 (2014). Supplementary Tab. 2 Summary statistics for canonical correspondence analyses for the southern China dataset <30°N (Cao et al., 2014). Pann – annual precipitation, Mtwa – mean temperature of the warmest month; Mtco – mean temperature of the coldest month; Tann mean annual temperature. -

Download This PDF File

SEEING DIAN THROUGH BARBARIAN EYES Aedeen Cremin The Australian National University; [email protected] ABSTRACT (Rode 2004:326). Men are the only people shown as individ- The Late Bronze Age burial sites in the Dian region of Yun- uals while women are seen in communal situations. There do nan are known for the originality, wealth and variety of their not seem to be any family scenes and only a few images of bronze artefacts. This paper examines a set of published im- children. ages of cattle and textiles in an attempt to see the Dian world A high level of craftsmanship is evidenced early on at in its own terms. It notes the transfer of decoration between Dabona, outside the Dian area proper. The tomb contained a bronzes and textiles and considers the apotropaic nature of house-shaped coffin, 2.43 x 0.790 x 0.765 m, made of seven some items. pieces of sheet bronze, decorated on all visible surfaces (HKMH 2004:96-97). It demonstrates some of the metallur- INTRODUCTION gical accomplishments of the Dian cultures, which include It will take years for archaeologists to fully understand the lost-wax, chasing and engraving (Barnard 1996-97:7-16, 59- more than 10,000 bronze artefacts recovered from the 28 sites 61). The coffin alloy is high in copper and contains some lead excavated in the Dian region between 1995 and 2005. The as well as tin: Cu 89.6, Sn 5.02, Pb 2.25 (Pirazzoli- sites are generally coeval with the Warring States, Qin and T‟Serstevens 1974:147-148).