212 2020 31 1503 27229 Jud

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Sr. No. Name of the Person Relationship

Tata Chemicals Limited List of Related party under SEBI (Listing Obligations and Disclosure Requirements) Regulations, 2015 / The Companies Act, 2013 as on 31st March, 2017 (as per IND AS 24) Listing Regulations / The Companies Act, 2013 reference Sr. Name of the Person Relationship Nature [Section 2(76) of No. CA, 2013 + Regulation 2 (zb) of LR] Directors, Key Managerial Personnel & Related Parties 1 Mr. Nasser Munjee Director (Independent, Non - Executive) 2 Mrs. Subur Ahmad Munjee Director's Relative 3 Smt. Niamat Mukhtar Munjee Director's Relative 4 Master Akbar Azaan Munjee Director's Relative 5 Smt. Sorayyah Kanji Director's Relative 6 Aarusha Homes Pvt. Ltd A private company in which a director is a member or director 7 Aga Khan Rural Support Programme, India (AKRSP,I) A private company in which a director is a member or director 8 Indian Institute of Human Settlements (Pvt Ltd) (Section 8) A private company in which a director is a member or director 9 Dr. Y.S.P. Thorat Director (Independent, Non - Executive) 10 Smt Usha Thorat Director's Relative 11 Smt Abha Thorat-Shah Director's Relative 12 Smt Aditi Thorat-Mortimer Director's Relative 13 Shri Darshak Shah Director's Relative 14 Shri Owen Mortimer Director's Relative 15 Ambit Holdings Pvt. Ltd (Merged with Ambit Private Limited) A private company in which a director is a member or director 16 Sahayog Micro Management (Pvt Ltd) (Section 8) A private company in which a director is a member or director 17 Syngenta Foundation India (Private Company) (Section 8) A private company in which a director is a member or director 18 Financial Benchmarks India Private Limited A private company in which a relative is a member or director 19 Sahayog Clean Milk Pvt. -

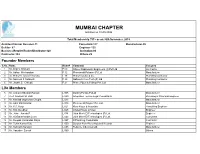

IPA Mumbai Membership As on 31 May 2019.Xlsx

MUMBAI CHAPTER Installed on 18-09-2005 Total Membership 745 - as on 30th November, 2019 Architect/Interior Designer-11 Consultant-117 Manufacturer-95 Builder- 87 Engineer-120 Business/Retailer/Trader/Distributor-128 Institution-04 Contractor-154 Others-29 Founder Members S.No. Name Mem # Company Category 1 Mr. Dilip V. Bhimani F 09 Shree Padmavati Engineers (I) Pvt Ltd Contractor 2 Mr. Adhar Mirchandani F 12 Phenoweld Polymer (P) Ltd Manufacturer 3 Dr. Phiroze Framroze Karaka F 19 Phiroz Karaka & Co. Plumbing Contractor 4 Mr. Nariman F Nallaseth F 20 Nallaseth Com Tech (P) Ltd Plumbing Contractor 5 Mr. Jayant S. Chheda F 21 Prince Pipes & Fittings Pvt. Ltd Manufacturer Life Members 6 Mr. Avinash Bhaskar Ranade L 005 Darling Pumps PvtLtd Manufacturer 7 Prof. Subhash M Patil L 009 Integrated Techno-Legal Consultants Plumbing & Structural Engineer 8 Mr. Keshab Jagmohan Chopra L 013 Manufacturer 9 Mr. Adar Mirchandani L 018 Phenoweld Polymer Pvt. Ltd. Manufacturer 10 Mr. K.S. Kogje L 021 Kisor Kogje & Associate Consulting Engineer 11 Mr. K.D. Deodhar L 025 Chalet Hotels Limited Engineer 12 Mr. John Joseph P. L 034 John Mech-El Technologies (P) Ltd. Engineer 13 Mr. Ajit Balachandra Joshi L 043 John Mech-El Technologies (P) Ltd. Consultant 14 Mr. Deepak Karsandas Daiya L 047 D'Plumbing Consultants Contractor 15 Mr. Tuhin Kumar Das L 050 Sarovar Park Plaza Hotels & Resorts Engineer 16 Mr. Subhash Sanzgiri L 055 Reliance Industries Ltd. Manufacturer 17 Mr. Vasudev Suresh L 069 Others 18 Mr. Mantripragada Prakash Kumar L 078 Unicorn Holdings (P) Ltd. Hotel Industries 19 Mr. -

Annual Report 2011-2012

Cover image: All photographs are of associates of Tata Consultancy Services The Annual General Meeting will be held on Friday, June 29, 2012, at Birla Matushri Sabhagar, Sir V. T. Marg, New Marine Lines, Mumbai 400020, at 3.30 p.m. As a measure of economy, copies of the Annual Report will not be distributed at the Annual General Meeting. Members are requested to bring their copies to the meeting. Contents Board of Directors 2 Financial Highlights 4 Our Leadership Team 5 Letter from CEO 6 Key Trends (FY 2005 - 2012) 8 Management Team 10 Directors’ Report 12 Management Discussion and Analysis 21 Corporate Governance Report 58 Consolidated Financial Statements Auditors’ Report 75 Consolidated Balance Sheet 76 Consolidated Statement of Profit and Loss 77 Consolidated Cash Flow Statement 78 Notes forming part of the Consolidated Financial Statements 79 Unconsolidated Financial Statements Auditors’ Report 111 Balance Sheet 114 Statement of Profit and Loss 115 Cash Flow Statement 116 Notes forming part of the Financial Statements 117 Statement under Section 212 of the Companies Act, 1956 relating to subsidiary companies 150 Board of Directors As of April 02, 2012 1 R N Tata 2 S Ramadorai 3 A Mehta Chairman Vice Chairman Director 4 V Thyagarajan 5 C M Christensen 6 R Sommer Director Director Director 7 Laura Cha 8 V Kelkar 9 I Hussain Director Director Director 10 N Chandrasekaran 11 S Mahalingam 12 P A Vandrevala Chief Executive Officer Chief Financial Officer Director and Managing Director and Executive Director 13 O P Bhatt 14 C P Mistry Director -

The Tata-Mistry Dispute: Quo Vadis, HR News, Ethrworld

05/10/2020 The Tata-Mistry Dispute: Quo Vadis, HR News, ETHRWorld NEWS SITES Sign in/Sign up Follow us: NEWS TRENDS WORKPLACE 4.0 HRTECH HR TV ENGAGE ADVISORY BOARD BRAND SOLUTIONS INTERVIEWS INDUSTRY EXPERT SPEAK CXO MOVEMENT INTERNATIONAL CAREERS FOR TOMORROW WHITEPAPER MORE HR News / Latest HR News / Industry The Tata-Mistry Subscribe to our Newsletters 100000+ Industry Leaders Dispute: Quo Vadis have already joined If the reported eorts of the two groups to settle their Your Email JOIN NO dispute before the next hearing were to succeed, it would mean a lost opportunity to not have the Supreme Court of India weigh in on the foundational principles of corporate governance—that of voice and exit for INDUSTRY shareholders—that this dispute is about. 28 mins ago ETHRWorld Contributor October 01, 2020, 20:40 IST Mumbai: Bidi workers struggle amid COVID-19 lockdown 2 hrs ago Over 1 lakh local shops, kiranas to facilitate Amazon India's delivery this festive season Ratan Tata (L) and Cyrus Mistry (R) https://hr.economictimes.indiatimes.com/news/industry/the-tata-mistry-dispute-quo-vadis/78431843 1/11 05/10/2020 The Tata-Mistry Dispute: Quo Vadis, HR News, ETHRWorld By J Ramachandran, Savithran Ramesh, K S 2 hrs ago Paytm, Manikandan other startups vow to Last week, the Shapoorji Pallonji Group (SP Group) ght announced its intention to exit the Tata Group after Google's clout: the Supreme Court restrained it from further pledging Report its shares in Tata Sons until the next hearing. The SP Group’s decision signals a rather bitter end to the 2 hrs ago seven-decades-long relationship that turned publicly Tourism businesses sour in 2016 with the abrupt dismissal of Cyrus Mistry hit as sta as Chairman of Tata Sons. -

Trent Hypermarket Ties up with Future Consumer Enterprise Ltd to Retail a Wide Range of Products ~A First of Its Kind Tie-Up

Trent Hypermarket ties up with Future Consumer Enterprise Ltd to retail a wide range of products ~A first of its kind tie-up that aims to bring customers of Star Bazaar, a unique product-price proposition~ Mumbai, 3rd March, 2016: Star, a TATA & TESCO enterprise, has tied up with Future Consumer Enterprise Ltd. (FCEL), to launch a wide range of food and non-food products across Star Bazaar stores. Star Bazaar aims to launch close to 148 SKUs across 10 FCEL brands with a view to provide their customers a unique product price proposition. FCEL’s portfolio includes popular consumer brands in the food category like ‘Sunkist’, ‘Tasty Treat’, “Karmiq” “Desi Atta” and ‘Fresh & Pure’; while “Think Skin”, ‘Clean Mate’ and ‘Care Mate’ constitute the non-food category. The FCEL range will be made available across large format hypermarkets of Star Bazaar in its initial phase. While this alliance offers customers a unique advantage of accessing everyday products at a great price, the launch will also see exclusive offers and promotions for Star’s Club card loyalty members. This association aims to serve the customers an unmatched array of products and introduce services that will see the store as a one stop destination for all daily household needs. Speaking on the launch, Mr. Jamshed Daboo, Managing Director, Trent Hypermarket Ltd. said, “We are excited about our collaboration with Future Consumer Enterprise to retail their flagship brands. With this tie- up, we will be bringing our customers an extensive range of high quality food products and non-food merchandise. Our objective is to enhance our existing range and ensure we address the growing needs of customers to access unique products at affordable price points” Mr. -

Jamsetji Tata (1839-1904) February 10, 2004 Life in Business Community Quotes Tributes Trusts Pictures

Jamsetji Tata (1839-1904) February 10, 2004 Life in Business Community Quotes Tributes Trusts pictures Jamsetji Tata's business philosophy was enshrined in values that made the country and its people partners in and beneficiaries of the wealth-creation process There are many reasons why India is beginning to shine on the economic front. One of the less-trumpeted ones can be traced to the late 19th century, when a band of homegrown entrepreneurs laid the seeds of indigenous industrialisation. The outstanding Indian businessman of the time was Jamsetji Nusserwanji Tata, industrialist, nationalist, humanist and the founder of the House of Tata. The industrialist in Jamsetji Tata was a pioneer and a visionary. The nationalist in him believed unwaveringly that the fruits of his business success would enrich a country he cared deeply about. But what made Jamsetji Tata truly unique, the quality that places him in the pantheon of modern India's greatest sons, was his humaneness. Jamsetji Tata rose to prominence in an era during which rapacious capitalism was the order of the day. America's 'robber barons' and their equivalents elsewhere in the world, including India, had come to define what the enterprise of moneymaking was all about: cruel to workers and uncaring of society, predatory in nature and ravenous in creed. Jamsetji Tata, though, was cut from a different cloth. The distinctive structure the Tata Group came to adopt, with a Related Articles huge part of its assets being held by trusts devoted to ploughing The giant who touched money into social-development initiatives, can be traced directly tomorrow to the empathy embedded in the founder's philosophy of Standing tall business. -

Mr. Gilbert Paustine Baptist, Managing Director Promoters of Our Company: Mr

Draft Prospectus Dated: September 28, 2015 Please read section 32 of Companies Act, 2013 (To be updated upon ROC filing) 100% Fixed Price Issue MALAIKA APPLIANCES LIMITED Our Company was incorporated as Malaika Appliances Private Limited under the provisions of the Companies Act, 1956 vide certificate of incorporation dated June 07, 1995, in Mumbai. Further, our Company was converted into public limited company vide fresh certificate of incorporation dated September 01, 2015. The Corporate Identification Number of Our Company is U25207MH1995PLC089266. For details of change in registered office of our Company please refer to chapter titled “Our History and Certain Other Corporate Matters” beginning on page 90 of this Draft Prospectus. Registered Office: Malaika Estate, Raje Shivaji Nagar, Sakivihar Road, Powai Mumbai-400072, Maharashtra Tel No: +91-22-2857 9686; Fax No: +91-22-2857 5665; E-mail: [email protected]; Website: www.malaikagroup.in Contact Person: Mr. Gilbert Paustine Baptist, Managing Director Promoters of our Company: Mr. Gilbert Paustine Baptist & Mrs. Marceline Jpquim Baptist THE ISSUE PUBLIC ISSUE OF 12,00,000 EQUITY SHARES OF FACE VALUE OF Rs. 10/- EACH FULLY PAID UP OF MALAIKA APPLIANCES LIMITED (“MALAIKA” OR THE “COMPANY” OR THE “ISSUER”) FOR CASH AT A PRICE OF Rs. 24/- PER EQUITY SHARE (THE “ISSUE PRICE”) (INCLUDING A SHARE PREMIUM OF Rs. 14/- PER EQUITY SHARE AGGREGATING Rs. 288.00 LAKHS (THE “ISSUE”) BY OUR COMPANY, OF WHICH 60,000 EQUITY SHARES OF Rs.10/- FULLY PAID UP EACH WILL BE RESERVED FOR SUBSCRIPTION BY MARKET MAKER TO THE ISSUE (“MARKET MAKER RESERVATION PORTION”). THE ISSUE LESS THE MARKET MAKER RESERVATION PORTION I.E. -

Presentation Title ( Arial, Font Size 28 )

PresentationThe Tata Power Title (Company Arial, Font size Ltd. 28 ) Date, Venue, etc ..( Arial, January Font size 18 2013 ) …Message Box ( Arial, Font size 18 Bold) Disclaimer •Certain statements made in this presentation may not be based on historical information or facts and may be “forward looking statements”, including those relating to The Tata Power Company Limited’s general business plans and strategy, its future outlook and growth prospects, and future developments in its industry and its competitive and regulatory environment. Actual results may differ materially from these forward-looking statements due to a number of factors, including future changes or developments in The Tata Power Company Limited’s business, its competitive environment, its ability to implement its strategies and initiatives and respond to technological changes and political, economic, regulatory and social conditions in India. •This presentation does not constitute a prospectus, offering circular or offering memorandum or an offer to acquire any Shares and should not be considered as a recommendation that any investor should subscribe for or purchase any of The Tata Power Company Limited’s Shares. Neither this presentation nor any other documentation or information (or any part thereof) delivered or supplied under or in relation to the Shares shall be deemed to constitute an offer of or an invitation by or on behalf of The Tata Power Company Limited. •The Company, as such, makes no representation or warranty, express or implied, as to, and do not accept any responsibility or liability with respect to, the fairness, accuracy, completeness or correctness of any information or opinions contained herein. -

Tata Sons - Passing the Baton.Docx

C:\Users\Firdoshktolat\Documents\Interesting\Tatas\Tata Sons - Passing The Baton.Docx TATA SONS: PASSING THE BATON By Jehangir Pocha The author is the co-promoter of INX News This article appeared in Forbes India Magazine of 16 December, 2011 http://forbesindia.com/article/boardroom/tata-sons-passing-the-baton/31052/0#ixzz1k4cATEGO There's a continuing thread of history in Cyrus Mistry's appointment as Ratan Tata's successor. But the move is also testimony to Tata's professionalism and sincerity. The passing of a crown is always a delicate affair. In 1991, when J.R.D. Tata handed his to Ratan Naval Tata, his courtiers had rebelled. It took time for RNT to subdue the satraps and prove JRD’s decision on his successor was perhaps his finest. But then JRD was always renowned for his ability to pick men. The circumstances around anointing RNT’s successor exactly two decades later were rather different. The world and the Tata’s had changed. It would take more than an arbitrary announcement from RNT to achieve a smooth succession in what is now one of the world’s largest conglomerates. So, if Cyrus P. Mistry is the first Tata head to have been crowned by a committee rather than a King, and the first from outside India Inc.’s first family, it is a testament to Tatas’ ability to move with the times. Yet, to those who know Tatas and its history, there is also no doubt that there is a continuing thread of history in Mistry’s appointment. Ties between the Mistry and Tata families have been close — and contentious — ever since 1936 when Cyrus’s grandfather Shapoorji Pallonji Mistry bought 17.5% of Tatas’ main holding company, Tata Sons. -

Mumbai Collector's Details of Leased Government Land In

FSI Rent at RR CRRNO L_RNT CSNO DIVISION HOLDER AREA COMM_DT PR_YR Rrrate Value 3 7% page no. 7602 130.90 2903 BHL MANJULABAI PRAGJI MAVJI 54.72 1/10/1964 50 57500 3146400 9439200 660744 62 7603 214.50 2909 BHL KESHAVRAM PITAMBARDAS PANCHAL & 1 ORS 55.18 1/1/1957 50 57500 3172850 9518550 666299 62 7604 65.25 2910-PT BHL THE MUNICIPAL CORPORATION OF THE CITY OF BOMBAY 108.88 1/1/1957 50 57500 6260600 18781800 1314726 62 7605 100.00 2911 BHL AJITKUMAR JAMNADAS & BORS 66.89 1/20/1963 50 57500 3846175 11538525 807697 62 7606 34.00 163 MZN PANDHARINATH MORESHWAR PATHARE 71.07 11/26/1957 50 40100 2849907 8549721 598480 75 7607 96.75 723 MZN SHIRINBAI FAKRUDDIN KARIMBHAI BOOTWALA 649.67 9/5/1914 99 42000 27286140 81858420 5730089 77 7608 379.70 719 + MZN GAJANAN RAMCHANDRA SAKHAL KAR & TWO ORS 4791.84 4/1/1913 99 42000 201257280 603771840 42264029 77 7609 175.74 717 MZN FIROZSHAH SHAVAKSHAH SHROFF 2171.51 4/1/1913 99 42000 91203420 273610260 19152718 77 7609A 164.90 718 MZN SMT.PADAMA ALISS PURNIMA W/F OF PARIMAL S.CHITALIA 2643.83 4/1/1913 99 42000 111040860 333122580 23318581 77 7616 111.00 80 CLB HIRABAI KAIKHORA JAMSHEDJI MODY & 3 ORS 1079.53 12/1/1928 999 7617 28.76 47 CLB RESERVE BANK OF INDIA 1768.40 12/1/1907 99 222800 393999520 1181998560 82739899 49 7618 85.11 46 CLB RUCHI PROPERTIES PVT.LTD. 1647.25 7/7/1914 999 7619 68.30 45 CLB RUCHI PROPERTIES PVT. -

Credo) Workshop Nd Th 22 to 26 November 2015

International Collaboration for Research methods Development in Oncology (CReDO) workshop nd th 22 to 26 November 2015 CReDO Shaping research ideas Organized by: Tata Memorial Centre, Mumbai National Cancer Grid of India Supported by Tata Trusts, Mumbai Tata Memorial Centre, Mumbai National Cancer Institute, USA King's College, London About the workshop The Tata Memorial Centre, Mumbai and the National Cancer Grid of India announce a five-day residential workshop on clinical research protocol development to be held in Mumbai between 22nd and 26th November 2015. This intensive protocol development workshop is modeled on similar workshops held in the United States (Vail), Europe (Flims) and Australia (ACORD). The main collaborators for the workshop are the National Cancer Institute (NCI), USA, King's College, London, the Medical Research Council-Clinical Trials Unit (MRC-CTU) at University College London and the Australia and Asia-Pacific Clinical Oncology Research and Development (ACORD) group, Australia. The objective of this workshop is to train researchers in oncology in various aspects of clinical trial design and to help them to develop a research idea into a structured protocol. Participation is open to researchers with training in surgical, medical or radiation oncology or any branch related to oncology. Preference will be given to early and middle-level researchers working in an academic setting who can demonstrate commitment to continuing research in oncology. The format of the workshop is a combination of protocol development group sessions, didactic talks, small-group breakaway sessions, office-hours (one-to-one direct consultation with experts) and “homework”. The faculty will consist of international and national experts with extensive experience in oncology research and training in research methodology workshops. -

Strategy Embedded Value of Tata Sons in Group

EQUITY RESEARCH India | Equity Strategy Strategy Exhibit 1 - Value of Tata Group Embedded Value of Tata Sons in Group Cos companies holding in Tata Sons Value of holdings in Tata Sons based Value of holdings in Tata Company Name Market Cap (Rs mn) 6 October 2020 on listed investment (Rs mn) Sons (as % of Mcap) Tata Chemicals 78,478 198,704 253.2 Tata Power 172,069 129,525 75.3 The Indian Hotels Company 120,353 87,347 72.6 Key Takeaway Tata Steel 434,912 240,203 55.2 Tata Motors 445,242 240,203 53.9 Financial troubles at the Shapoorji Palanji (SP) group, which holds an 18% stake in . Tata Consumer Products 463,754 34,065 7.3 Source: Company annual reports, Jefferies Tata Sons – the group hold co – has triggered debate on Tata Sons' worth. Tata Sons’ holdings across 14 listed cos works out to US$100bn+. SP group's reported asking price is c.20% higher. Several listed Tata group cos hold a stake in Tata Sons. For Tata Chem, Indian Hotels, Tata Power, Tata Steel and Tamo the value of investment in Tata Sons is more than 50% of the market cap. This report is intended for [email protected]. Unauthorized distribution prohibited. Stress at the SP group prompting likely Tata Sons breakup. The SP group's weak liquidity situation was made clear recently when on 25th Sep'20 it defaulted on a Union Bank owned Rs2bn commercial paper. Earlier, the group had tried to pledge part of its 18.4% shareholding in Tata Sons to shore up funding for its own businesses; but the same was stayed by the Supreme court (next hearing 28th October).