CRACKDOWN at LETPADAN

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Mimu875v01 120626 3W Livelihoods South East

Myanmar Information Management Unit 3W South East of Myanmar Livelihoods Border and Country Based Organizations Presence by Township Budalin Thantlang 94°23'EKani Wetlet 96°4'E Kyaukme 97°45'E 99°26'E 101°7'E Ayadaw Madaya Pangsang Hakha Nawnghkio Mongyai Yinmabin Hsipaw Tangyan Gangaw SAGAING Monywa Sagaing Mandalay Myinmu Pale .! Pyinoolwin Mongyang Madupi Salingyi .! Matman CHINA Ngazun Sagaing Tilin 1 Tada-U 1 1 2 Monghsu Mongkhet CHIN Myaing Yesagyo Kyaukse Myingyan 1 Mongkaung Kyethi Mongla Mindat Pauk Natogyi Lawksawk Kengtung Myittha Pakokku 1 1 Hopong Mongping Taungtha 1 2 Mongyawng Saw Wundwin Loilen Laihka Ü Nyaung-U Kunhing Seikphyu Mahlaing Ywangan Kanpetlet 1 21°6'N Paletwa 4 21°6'N MANDALAY 1 1 Monghpyak Kyaukpadaung Taunggyi Nansang Meiktila Thazi Pindaya SHAN (EAST) Chauk .! Salin 4 Mongnai Pyawbwe 2 Tachileik Minbya Sidoktaya Kalaw 2 Natmauk Yenangyaung 4 Taunggyi SHAN (SOUTH) Monghsat Yamethin Pwintbyu Nyaungshwe Magway Pinlaung 4 Mawkmai Myothit 1 Mongpan 3 .! Nay Pyi Hsihseng 1 Minbu Taw-Tatkon 3 Mongton Myebon Langkho Ngape Magway 3 Nay Pyi Taw LAOS Ann MAGWAY Taungdwingyi [(!Nay Pyi Taw- Loikaw Minhla Nay Pyi Pyinmana 3 .! 3 3 Sinbaungwe Taw-Lewe Shadaw Pekon 3 3 Loikaw 2 RAKHINE Thayet Demoso Mindon Aunglan 19°25'N Yedashe 1 KAYAH 19°25'N 4 Thandaunggyi Hpruso 2 Ramree Kamma 2 3 Toungup Paukkhaung Taungoo Bawlakhe Pyay Htantabin 2 Oktwin Hpasawng Paungde 1 Mese Padaung Thegon Nattalin BAGOPhyu (EAST) BAGO (WEST) 3 Zigon Thandwe Kyangin Kyaukkyi Okpho Kyauktaga Hpapun 1 Myanaung Shwegyin 5 Minhla Ingapu 3 Gwa Letpadan -

The Union Report the Union Report : Census Report Volume 2 Census Report Volume 2

THE REPUBLIC OF THE UNION OF MYANMAR The 2014 Myanmar Population and Housing Census The Union Report The Union Report : Census Report Volume 2 Volume Report : Census The Union Report Census Report Volume 2 Department of Population Ministry of Immigration and Population May 2015 The 2014 Myanmar Population and Housing Census The Union Report Census Report Volume 2 For more information contact: Department of Population Ministry of Immigration and Population Office No. 48 Nay Pyi Taw Tel: +95 67 431 062 www.dop.gov.mm May, 2015 Figure 1: Map of Myanmar by State, Region and District Census Report Volume 2 (Union) i Foreword The 2014 Myanmar Population and Housing Census (2014 MPHC) was conducted from 29th March to 10th April 2014 on a de facto basis. The successful planning and implementation of the census activities, followed by the timely release of the provisional results in August 2014 and now the main results in May 2015, is a clear testimony of the Government’s resolve to publish all information collected from respondents in accordance with the Population and Housing Census Law No. 19 of 2013. It is my hope that the main census results will be interpreted correctly and will effectively inform the planning and decision-making processes in our quest for national development. The census structures put in place, including the Central Census Commission, Census Committees and Offices at all administrative levels and the International Technical Advisory Board (ITAB), a group of 15 experts from different countries and institutions involved in censuses and statistics internationally, provided the requisite administrative and technical inputs for the implementation of the census. -

October Chronology (Eng)

October 2015, Chronology Summary of the Current Situation As of the end of October, there are 112 political prisoners incarcerated in Burma and 486 activists currently awaiting trial for political actions. Detained Facebook Activists Patrick Kum Jaa Lee and Chaw Sandy Tun Accessed October 2015 Table of Contents Month in Review Detentions Incarcerations Conditions of Detentions Demonstrations and Related Restrictions on Political and Civil Liberties Land Issues Key International and Domestic Developments Conclusion Links and Resources “There can be no national reconciliation in Burma, as long as there are political prisoners” October 2015, Chronology MONTH IN REVIEW This month, 10 political activists were arrested political prisoners is preventing the upcoming in total, eight of whom are detained. Thirty- election from being free and fair. One were sentenced, and eight were released. Despite concerns over the legitimacy of the Nine political prisoners are reported to be in upcoming election, new arrests continued this bad health. month. Lu Zaw Soe Win, Patrick Kum Jaa Lee The Letpadan case was still not resolved this and Chaw Sandy Tun were all arrested and month, and 61 students and activists remain detained for allegedly posting to Facebook detained for charges relating to their images or insults defaming the government and participation in the National Education Bill received charges either under the protests in March. Fortify Rights and the Telecommunications Law or the Electronic Harvard Law School International Human Transactions Law. Patrick Kum Jaa Lee and Rights Clinic released a report detailing the Chaw Sandy Tun remain in detention. Maung abusive tactics used by police officials in the Saungkha also received charges under the violent crackdown. -

Desk Review Cover and Contents.Indd

BASELINE ASSESSMENT OF COMMUNITY BASED TB SERVICES IN 8 ENGAGE-TB PRIORITY COUNTRIES WHO/CDS/GTB/THC/18.34 © World Health Organization 2018 Some rights reserved. This work is available under the Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-ShareAlike 3.0 IGO licence (CC BY-NC-SA 3.0 IGO; https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-sa/3.0/igo). Under the terms of this licence, you may copy, redistribute and adapt the work for non-commercial purposes, provided the work is appropriately cited, as indicated below. In any use of this work, there should be no suggestion that WHO endorses any specific organization, products or services. The use of the WHO logo is not permitted. If you adapt the work, then you must license your work under the same or equivalent Creative Commons licence. If you create a translation of this work, you should add the following disclaimer along with the suggested citation: “This translation was not created by the World Health Organization (WHO). WHO is not responsible for the content or accuracy of this translation. The original English edition shall be the binding and authentic edition”. Any mediation relating to disputes arising under the licence shall be conducted in accordance with the mediation rules of the World Intellectual Property Organization. Suggested citation. Baseline assessment of community based TB services in 8 WHO ENGAGE-TB priority countries. Geneva: World Health Organization; 2018 (WHO/CDS/GTB/THC/18.34). Licence: CC BY-NC-SA 3.0 IGO. Cataloguing-in-Publication (CIP) data. CIP data are available at http://apps.who.int/iris. -

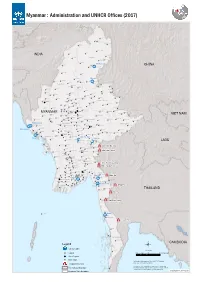

Myanmar : Administration and UNHCR Offices (2017)

Myanmar : Administration and UNHCR Offices (2017) Nawngmun Puta-O Machanbaw Khaunglanhpu Nanyun Sumprabum Lahe Tanai INDIA Tsawlaw Hkamti Kachin Chipwi Injangyang Hpakan Myitkyina Lay Shi Myitkyina CHINA Mogaung Waingmaw Homalin Mohnyin Banmauk Bhamo Paungbyin Bhamo Tamu Indaw Shwegu Momauk Pinlebu Katha Sagaing Mansi Muse Wuntho Konkyan Kawlin Tigyaing Namhkan Tonzang Mawlaik Laukkaing Mabein Kutkai Hopang Tedim Kyunhla Hseni Manton Kunlong Kale Kalewa Kanbalu Mongmit Namtu Taze Mogoke Namhsan Lashio Mongmao Falam Mingin Thabeikkyin Ye-U Khin-U Shan (North) ThantlangHakha Tabayin Hsipaw Namphan ShweboSingu Kyaukme Tangyan Kani Budalin Mongyai Wetlet Nawnghkio Ayadaw Gangaw Madaya Pangsang Chin Yinmabin Monywa Pyinoolwin Salingyi Matman Pale MyinmuNgazunSagaing Kyethi Monghsu Chaung-U Mongyang MYANMAR Myaung Tada-U Mongkhet Tilin Yesagyo Matupi Myaing Sintgaing Kyaukse Mongkaung VIET NAM Mongla Pauk MyingyanNatogyi Myittha Mindat Pakokku Mongping Paletwa Taungtha Shan (South) Laihka Kunhing Kengtung Kanpetlet Nyaung-U Saw Ywangan Lawksawk Mongyawng MahlaingWundwin Buthidaung Mandalay Seikphyu Pindaya Loilen Shan (East) Buthidaung Kyauktaw Chauk Kyaukpadaung MeiktilaThazi Taunggyi Hopong Nansang Monghpyak Maungdaw Kalaw Nyaungshwe Mrauk-U Salin Pyawbwe Maungdaw Mongnai Monghsat Sidoktaya Yamethin Tachileik Minbya Pwintbyu Magway Langkho Mongpan Mongton Natmauk Mawkmai Sittwe Magway Myothit Tatkon Pinlaung Hsihseng Ngape Minbu Taungdwingyi Rakhine Minhla Nay Pyi Taw Sittwe Ann Loikaw Sinbaungwe Pyinma!^na Nay Pyi Taw City Loikaw LAOS Lewe -

Eligible Voters Per Pyithu Hluttaw Constituency 2015 Elections

Myanmar Information Management Unit Eligible Voters per Pyithu Hluttaw Constituency 2015 Elections 90° E 95° E 100° E This map shows the variation in the number of registered voters per township according to UEC data. Nawngmun BHUTAN Puta-O Machanbaw Nanyun Khaunglanhpu Sumprabum Tsawlaw Tanai Lahe Injangyang INDIA Hpakant KACHIN Hkamti Chipwi Hpakant Waingmaw Lay Shi Mogaung N N ° CHINA ° 5 Homalin Myitkyina 5 2 Mohnyin 2 Momauk Banmauk Indaw BANGLADESH Shwegu Bhamo PaungbySinAGAING Katha Tamu Pinlebu Konkyan Wuntho Mansi Muse Kawlin Tigyaing Tonzang Mawlaik Namhkan Kutkai Laukkaing Mabein Kyunhla Thabeikkyin Kunlong Tedim Manton Hopang Kalewa Hseni Kale Kanbalu Mongmit Taze Namtu Hopang Falam Namhsan Lashio Mongmao Mingin Ye-U Mogoke Pangwaun Thantlang Khin-U Tabayin Kyaukme Shwebo Singu Tangyan Narphan Kani Hakha Budalin Wetlet Nawnghkio Mongyai Pangsang Ayadaw Madaya Hsipaw Yinmabin Monywa Sagaing Patheingyi Gangaw Salingyi VIETNAM Pale Myinmu Mongyang Matupi Chaung-U Ngazun Pyinoolwin Kyethi Myaung Matman CHIN Tilin Myaing Sintgaing Mongkaung Monghsu Mongkhet Tada-U Kyaukse Lawksawk Mongla Pauk Myingyan Paletwa Mindat Yesagyo Natogyi Saw Myittha SHAN Pakokku Hopong Laihka Maungdaw Ywangan Kunhing Mongping Kengtung Mongyawng MTaAunNgthDa ALWAundYwin Buthidaung Kanpetlet Seikphyu Nyaung-U Mahlaing Pindaya Loilen Kyauktaw Nansang Monghpyak Kyaukpadaung Meiktila Thazi Taunggyi Chauk Salin Kalaw Mongnai Ponnagyun Pyawbwe Tachileik Minbya Monghsat Rathedaung Mrauk-U Sidoktaya Yenangyaung Nyaungshwe RAKHINE Natmauk Yamethin Pwintbyu Mawkmai -

Administrative Map

Myanmar Information Management Unit Myanmar Administrative Map 94°E 96°E 98°E 100°E India China Bhutan Bangladesh Along India Vietnam KACHIN Myanmar Dong Laos South China Sea Bay of Bengal / Passighat China Thailand Daporija Masheng SAGAING 28°N Andaman Sea Philippines Tezu 28°N Cambodia Sea of the Philippine Gulf of Thailand Bangladesh Pannandin !( Gongshan CHIN NAWNGMUN Sulu Sea Namsai Township SHAN MANDALAY Brunei Malaysia Nawngmun MAGWAY Laos Tinsukia !( Dibrugarh NAY PYI TAW India Ocean RAKHINE Singapore Digboi Lamadi KAYAH o Taipi Duidam (! !( Machanbaw BAGO Margherita Puta-O !( Bomdi La !( PaPannssaauunngg North Lakhimpur KHAUNGLANHPU Weixi Bay of Bengal Township Itanagar PUTA-O MACHANBAW Indonesia Township Township Thailand YAN GON KAY IN r Khaunglanhpu e !( AYE YARWADY MON v Khonsa i Nanyun R Timor Sea (! Gulf of Sibsagar a Martaban k Fugong H i l NANYUN a Township Don Hee M !( Jorhat Mon Andaman Sea !(Shin Bway Yang r Tezpur e TANAI v i TANINTHARYI NNaaggaa Township R Sumprabum !( a Golaghat k SSeellff--AAddmmiinniisstteerreedd ZZoonnee SUMPRABUM Township i H Gulf of a m Thailand Myanmar administrative Structure N Bejiang Mangaldai TSAWLAW LAHE !( Tanai Township Union Territory (1) Nawgong(nagaon) Township (! Lahe State (7) Mokokchung Tuensang Lanping Region (7) KACHIN INDIA !(Tsawlaw Zunheboto Hkamti INJANGYANG Hojai Htan Par Kway (! Township !( 26°N o(! 26°N Dimapur !( Chipwi CHIPWI Liuku r Township e Injangyang iv !( R HKAMTI in w Township d HPAKANT MYITKYINA Lumding n i Township Township Kohima Mehuri Ch Pang War !(Hpakant -

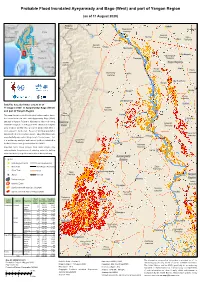

And Part of Yangon Region

Probable Flood Inundated Ayeyarwady and Bago (West) and part of Yangon Region (as of 11 August 2020) 95°0'E Padaung Nattalin Bhutan Township Shwedaung India China Township / Nattalin Bangladesh Tar Pun Township Zigon Zigon Kyangin Township Vietnam Myanmar Kyangin Nay Pyi Taw Batye (!^_ Township Myanaung Laos Yangon Gyobingauk (! Gyobingauk Thailand Kanaung Township Thandwe Bago Region Township Cambodia Monyo Okpho Okpho Township Township Myanaung In Pin Township Oe Thei Kone Monyo 18°0'N Htoogyi Minhla 18°0'N Minhla Township Me Za Li Kone Satellite detected water extent as of Sit Kwin 11 August 2020 in Ayeyarwady, Bago (West) Ingapu and part of Yangon Region Township Gwa Ingapu This map illustrates satellite-detected surface waters due to Township the current monsoon rains over Ayeyarwady, Bago (West) Letpadan and part of Yangon Region of Myanmar as observed from a Rakhine Letpadan Sentinel-1 image as of 11 August 2020. Within the analyzed State Township area of about 23,994 km2, a total of about 1,528 km2 of lands appear to be flooded. Based on Worldpop population Thayarwady data and the detected surface waters, about 209,225 people Hinthada Township are potentially exposed or living close to flooded areas. This Ta Loke Htaw is a preliminary analysis and has not yet been validated in Lemyethna Township the field. Please send ground feedback to MIMU. Lemyethna Hinthada Important Note: Flood analysis from radar images may Township underestimate the presence of standing waters in built-up Du Yar areas and densely vegetated areas due to -

Economic and Engineering Development of Burma, 1953

SIVE REFOTT "??• ■^r -a-^ "g-i -wr^ "w "|k T • i^UMiC AND ENG ^ X ^ ^.t M-j> M\. JL X^ DEVELOPMENT OF BURMA PREPARED FOR THE GOVERNMENT OF THE UNION OF BURMA VOLUME II AUGUST 1953 KNAPPEN TIPPETTS ABBETT MCCARTHY ENGINEERS IN ASSOCIATION WITH PIERCE MANAGEMENT, INC. AND ROBERT R. NATHAN ASSOCIATES, INC. ECONOMIC AND ENGINEERING DEVELOPMENT OF BURMA COMPREHENSIVE REPORT ECONOMIC AND ENGINEERING DEVELOPMENT OF BURMA PREPARED FOR THE GOVERNMENT OF THE UNION OF BURMA VOLUME II TELECOMMUNICATIONS POWER INDUSTRY AUGUST 1953 KNAPPEN TIPPETTS ABBETT McCARTHY ENGINEERS IN ASSOCIATION WITH PIERCE MANAGEMENT, INC. AND ROBERT R. NATHAN ASSOCIATES, INC. PRINTED AND BOUND IN GREAT BRITAIN BY HAZELL, WATSON & VINEY, LTD. AYLESBURY & I ONDON TABLE OF CONTENTS Letter of Transmittal II Foreword viii Page Page VOLUME I E. The Structure of the Revenue System 62 F. Banking Pohcy 67 PARTI G. Foreign Exchange and Foreign Trade Pohcy 72 INTRODUCTION H. Summary of Recommendations 74 CHAPTER I. RESOURCES FOR BURMA'S DEVELOPMENT CHAPTER V. ORGANIZATION FOR A. Introduction 3 COORDINATING THE PROGRAM B. Physical Geography 3 A. The Four Major Steps in Coordinating Economic Activity 76 C. Agriculture 5 B. Organization for Planning 77 D. Forests 8 C. Organization for Programming 78 E. Minerals 11 D. Staff for Planning and Programming 78 F. Water Resources 11 E. Organization and Procedure for Imple¬ G. Transportation 14 mentation of Economic and Functional H. Capital Resources 15 Pohcies 80 I. Human Resources 15 F. Organization for Progress Reporting and Expediting 81 CHAPTER II. THE TASK AHEAD G. Economic and Social Board Staff 82 A. -

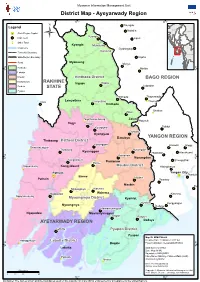

Ayeyarwady Region

Myanmar Information Management Unit District Map - Ayeyarwady Region 95° E 96° E Paungde Legend INDIA Nattalin CHINA .! State/Region Capital Kyangin Main Town Ü Zigon !( Other Town Kyangin Myanaung Coast Line !( Gyobingauk Kanaung Township Boundary THAILAND State/Region Boundary Okpho Road Myanaung Monyo N Kyeintali N ° Hinthada !( ° 8 Minhla 8 1 1 Labutta Maubin Hinthada District BAGO REGION Myaungmya RAKHINE Ingapu Ingapu Pathein STATE Letpadan Pyapon Hinthada Thayarwady Gwa Lemyethna Lemyethna !( Thonse Hinthada Okekan Zalun !( Ngathaingchaung Zalun !( Ahpyauk !( Yegyi Yegyi Kyonpyaw Taikkyi Danubyu Kyonpyaw Danubyu YANGON REGION Thabaung Pathein District Kyaunggon Hmawbi Hlegu Shwethaungyan !( Thabaung Nyaungdon Kyaunggon Htantabin Htaukkyant N N ° Pantanaw ° 7 7 1 Nyaungdon 1 Kangyidaunt Pantanaw Shwepyithar Einme Ngwesaung Kangyidaunt Maubin District !( Hlaingtharya Pathein Yangon City .! .! Thanlyin Einme Maubin Pathein Twantay Maubin Kyauktan Myaungmya Wakema Ngapudaw Wakema Kawhmu Ngayokekaung !( Myaungmya District Kyaiklat Kyaiklat Kungyangon Myaungmya Dedaye Mawlamyinegyun Ngapudaw Mawlamyinegyun Bogale Pyapon AYEYARWADY REGION Dedaye Labutta Pyapon District Pyapon Map ID: MIMU764v04 Hainggyikyun Creation Date: 23 October 2017.A4 N Labutta District N !( ° Bogale Projection/Datum: Geographic/WGS84 ° 6 6 1 1 Labutta Data Sources: MIMU Base Map: MIMU Boundaries: MIMU/WFP Pyinsalu Place Name: Ministry of Home Affairs (GAD) !( Ahmar translated by MIMU !( Email: [email protected] Website: www.themimu.info Kilometers Copyright © Myanmar Information Management Unit 2017. May be used free of charge with attribution. 0 10 20 40 95° E 96° E Disclaimer: The names shown and the boundaries used on this map do not imply official endorsement or acceptance by the United Nations.. -

MYANMAR Cyclone NARGIS Affected Areas V.1, 5 May 2008

176 172 110 Magway 251 105 263 223 146 268 259 256 MYANSMittwAe R 171 101 100 265 107 Cyclone NARGIS 162 116 103 141 86 115 127 266 RAKHINE STATE 83 Loikaw Affected Areas v.1, 5 May 2008 88 165 85 102 117 40 Ayeyarwady Division (MMR017) 96 KAYAH STATE Map Index Township Pcode 174 82 Myanmar Information 178 99 95 Managment Unit 1 Bogale MMR017024 48 37 2 Danubyu MMR017022 Pyay 50 84 3 Dedaye MMR017026 170 4 Einme MMR017015 BAGO DIVISION 33 87 5 Hinthada MMR017008 36 6 Ingapu MMR017013 34 47 (WEST)49 45 7 Kangyidaunt MMR017002 51 53 BAGO DIVISION 8 Kyaiklat MMR017025 177 MIMU 9 Kyangin MMR017012 9 54 (EAST) 10 Kyaunggon MMR017007 41 30 11 Kyonpyaw MMR017005 31 12 Labutta MMR017016 16 46 13 Lemyethna MMR017010 91 14 Maubin MMR017019 44 43 42 32 15 Mawlamyinegyun MMR017018 6 16 Myanaung MMR017011 35 17 Myaungmya MMR017014 164 28 18 Ngapudaw MMR017004 5 52 19 Nyaungdon MMR017021 13 27 39 20 Pantanaw MMR017020 26 152 21 Pathein MMR017001 318 Bago 155 22 Pyapon MMR017023 25 11 23 Thabaung MMR017003 2 38 MON 24 Wakema MMR017017 23 294 89 25 Yegyi MMR017006 10 295 STATE 26 Zalun MMR017009 19 29 AYEYARWADY 296 KAYIN STATE 20 160 21 DIVISION 300 Hpa-An Bago East Division (MMR007) Pathein 7 4 14 321 323 90 92 Map Index Township Pcode 324 158 24 303 27 Bago MMR007001 299 Mawlamyine 28 Daik-U MMR007007 17 8 156 29 Kawa MMR007003 18 301 94 30 Kyaukkyi MMR007011 15 3 153 154 31 Kyauktaga MMR007006 22 Yangon 32 Nyaunglebin MMR007005 157 33 Oktwin MMR007013 12 1 YANGON DIVISION 34 Phyu MMR007012 35 Shwegyin MMR007008 159 36 Tantabin MMR007014 37 Taungoo -

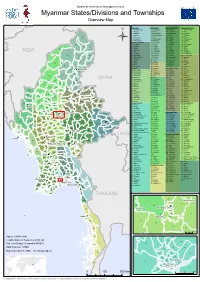

Myanmar States/Divisions and Townships Overview Map

Myanmar Information Management Unit Myanmar States/Divisions and Townships Overview Map Kayin State Kachin State Shan (South) State Bago West Division 1 Thandaunggyi 84 Nawngmun 165 Ywangan 246 Paukkhaung 2 Hpapun 85 Puta-O 166 Lawksawk 247 Pyay 3 Hlaingbwe 86 Machanbaw 167 Mongkaung 248 Padaung 4 Hpa-An 87 Khaunglanhpu 168 Kyethi 249 Paungde 84 5 Myawaddy 88 Tanai 169 Monghsu 250 Thegon 6 Kawkareik 89 Sumprabum 170 Pindaya 251 Shwedaung 7 Kyainseikgyi 90 Tsawlaw 171 Kalaw 252 Nattalin Ü Bago East Division 91 Injangyang 172 Taunggyi 253 Zigon 85 8 Yedashe 92 Chipwi 173 Hopong 254 Gyobingauk 86 87 9 Taungoo 93 Hpakan 174 Loilen 255 Okpho 118 10 Oktwin 94 Myitkyina 175 Laihka 256 Monyo 11 Htantabin 95 Mogaung 176 Nansang 257 Minhla INDIA 12 Phyu 96 Waingmaw 177 Kunhing 258 Letpadan 13 Kyaukkyi 97 Mohnyin 178 Mongnai 259 Thayarwady 119 88 89 90 14 Kyauktaga 98 Momauk 179 Pinlaung Magway Division 15 Nyaunglebin 99 Shwegu 180 Nyaungshwe 260 Gangaw 91 16 Shwegyin 100 Bhamo 181 Hsihseng 261 Tilin 17 Daik-U 101 Mansi 182 Mawkmai 262 Myaing 120 92 18 Bago Kayah State 183 Langkho 263 Yesagyo 93 19 Waw 102 Loikaw 184 Mongpan 264 Pauk 20 Thanatpin 103 Shadaw 185 Pekon 265 Pakokku Shan (North) State 121 ! 21 Kawa 104 Demoso 266 Saw 95 Myitkyina Rakhine State 105 Hpruso 186 Mabein 267 Seikphyu 96 22 Maungdaw 106 Bawlakhe 187 Mongmit 268 Chauk 94 23 Buthidaung 107 Hpasawng 188 Manton 269 Salin 97 122 24 Kyauktaw 108 Mese 189 Namhkan 270 Sidoktaya 25 Mrauk-U Chin State 190 Muse 271 Natmauk BANGLADESH CHINA 26 Ponnagyun 109 Tonzang 191 Kutkai 272 Yenangyaung