3Tic. T) Aliasy Cuba, and the Slection of 1856

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Destruction and Reconstruction of American Ideals in Herman Melville's Writings a Dissertation Pres

The Power of Nothingness: Destruction and Reconstruction of American Ideals in Herman Melville’s Writings A Dissertation Presented to The Faculty of the Graduate School of Letters Keio University In Partial Fulfillment of the Requirement for the Degree of Doctor of Philosophy in Literature by Shogo Tanokuchi July 2019 The Power of Nothingness: Destruction and Reconstruction of American Ideals in Herman Melville’s Writings Shogo Tanokuchi Keio University Contents Acknowledgments . ii List of Figures . v Introduction . 1 Creating Something out of Nothing Chapter 1 . 34 A Dead Author to Be Resurrected: The Ambiguity of American Democracy in Pierre: or, the Ambiguities Chapter 2 . 60 A Revolutionary Hero’s Transatlantic Crossings: Destruction and Reconstruction of “Americanism” in Israel Potter: His Fifty Yeas of Exile Chapter 3 . 83 The Revolutionary Ideals Manipulated: Re-figuration of the Founding Fathers in Battle-Pieces and Aspects of War Chapter 4 . 105 The Curious Gaze on Asian Junks: Melville’s Art of Exhibition Conclusion . 132 Kaleidoscopic Nothingness: Yoji Sakate’s Bartlebies and the Great East Japan Earthquake Works Cited . 148 Acknowledgements I am writing these acknowledgements in a dorm room in Palladium Hall, New York University. I came here to deliver my paper at the 12th International Melville Conference. While hearing the mild rain and the noisy construction of New York City, I look back over the “origins” of my ten-year study of Melville’s massive and elusive writings, which started in 2009 when I first encountered Melville as an undergraduate student at Keio University. It was at the 10th International Melville Conference, held at Keio University in 2015, that I decided upon the theme of my dissertation: “the power of nothingness” in Melville’s writings. -

Lauren N. Haumesser “Not Man Enough”: Gender And

Lauren N. Haumesser “Not man enough”: Gender and Democratic Campaign Tactics in the Election of 1856 Throughout the 1850s, the Democratic Party was frequently, as one contemporary put it, “not on speaking terms with itself.”1 Democrats disagreed on issues as fundamental as the scope of federal and state power, political economy, and even slavery. Americans had debated the relative power of the federal and state governments since the founding of the republic. Now, however, Democratic leaders had to adjudicate the dispute within their own party. Moderate Democrats emphasized states rights within the federal system, while radicals argued for states’ total sovereignty. Nor did Democrats agree on a vision for America’s economy. Southern planters celebrated agrarianism, while a group of Democrats who dubbed themselves the “Young Americans” believed the government should support economic development projects such as railroad development and harbor improvements.2 Party members did not even agree on the most important political issue of the day: slavery. The party and its members—like almost every American in the nineteenth century—were intensely racist. All Democrats agreed that blacks were biologically inferior. But Free Soil Democrats and slaveholding Democrats divided over whether slavery should be extended into America’s new western territories. 3 Free Soil Democrats, who were concentrated in New York, New Hampshire, Massachusetts, and Ohio, were suspicious of Southern planters. Free Soilers believed planters had allied with New England textile 1 Quoted in Jean Baker, Affairs of Party: The Political Culture of Northern Democrats in the Mid-Nineteenth Century (Ithaca, New York: Cornell University Press, 1983), 145. -

The Coming Crisis, the 1850S 8Th Edition

The Coming Crisis the 1850s I. American Communities A. Illinois Communities Debate Slavery 1. Lincoln-Douglas Debates II. America in 1850 A. Expansion and Growth 1. Territory 2. Population 3. South’s decline B. Politics, Culture, and National Identity 1. “American Renaissance” 2. Nathaniel Hawthorne a. The Scarlet Letter (1850) 3. Herman Melville a. Moby Dick (1851) 4. Harriet Beecher Stowe a. Uncle Tom’s Cabin (1851) III. Cracks in National Unity A. The Compromise of 1850 B. Political Parties Split over Slavery 1. Mexican War’s impact a. Slavery in the territories? 2. Second American Party System a. Whigs & Democrats b. Sectional division C. Congressional Divisions 1. Underlying issues 2. States’ Rights & Slavery a. John C. Calhoun b. States’ rights: nullification c. U.S. Constitution & slavery 3. Northern Fears of “The Slave Power” a. Sectional balance: slave v. free D. Two Communities, Two Perspectives 1. Territorial expansion & slavery 2. Basic rights & liberties 3. Sectional stereotypes E. Fugitive Slave Act 1. Underground Railroad 2. Effect of Slave Narratives a. Personal liberty laws 3. Provisions 4. Anthony Burns case 5. Frederick Douglass & Harriet Jacobs 6. Effect on the North D. The Election of 1852 1. National Party system threatened 2. Winfield Scott v. Franklin Pierce E. “Young America”: The Politics of Expansion 1. Pierce’s support 2. Filibusteros a. Caribbean & Central America 3. Cuba & Ostend Manifesto IV. The Crisis of the National Party System A. The Kansas-Nebraska Act (1854) 1. Stephen A. Douglas 2. Popular sovereignty 3. Political miscalculation B. “Bleeding Kansas” 1. Proslavery: Missouri a. “Border ruffians” 2. Antislavery: New England a. -

The Democratic Party and the Transformation of American Conservatism, 1847-1860

PRESERVING THE WHITE MAN’S REPUBLIC: THE DEMOCRATIC PARTY AND THE TRANSFORMATION OF AMERICAN CONSERVATISM, 1847-1860 Joshua A. Lynn A dissertation submitted to the faculty at the University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in the Department of History. Chapel Hill 2015 Approved by: Harry L. Watson William L. Barney Laura F. Edwards Joseph T. Glatthaar Michael Lienesch © 2015 Joshua A. Lynn ALL RIGHTS RESERVED ii ABSTRACT Joshua A. Lynn: Preserving the White Man’s Republic: The Democratic Party and the Transformation of American Conservatism, 1847-1860 (Under the direction of Harry L. Watson) In the late 1840s and 1850s, the American Democratic party redefined itself as “conservative.” Yet Democrats’ preexisting dedication to majoritarian democracy, liberal individualism, and white supremacy had not changed. Democrats believed that “fanatical” reformers, who opposed slavery and advanced the rights of African Americans and women, imperiled the white man’s republic they had crafted in the early 1800s. There were no more abstract notions of freedom to boundlessly unfold; there was only the existing liberty of white men to conserve. Democrats therefore recast democracy, previously a progressive means to expand rights, as a way for local majorities to police racial and gender boundaries. In the process, they reinvigorated American conservatism by placing it on a foundation of majoritarian democracy. Empowering white men to democratically govern all other Americans, Democrats contended, would preserve their prerogatives. With the policy of “popular sovereignty,” for instance, Democrats left slavery’s expansion to territorial settlers’ democratic decision-making. -

Full Text of the Ostend Manifesto

THE OSTEND MANIFESTO Aix-la-Chapelle, October 15, 1854 Sir: The undersigned, in compliance with the wish expressed by the President in the several confidential dispatches you have addressed to us, respectively, to that effect, have met in conference, first at Ostend, in Belgium, on the 9th, 10th, and 11th instants, and then at Aix-la- Chapelle, in Prussia, on the days next following, up to the date hereof. There has been a full and unreserved interchange of views and sentiments between us, which we are most happy to inform you has resulted in a cordial coincidence of opinion on the grave and important subjects submitted to our consideration. We have arrived at the conclusion, and are thoroughly convinced, that an immediate and earnest effort ought to be made by the government of the United States to purchase Cuba from Spain at any price for which it can be obtained, not exceeding the sum of $ (this item was left blank). The proposal should, in our opinion, be made in such a manner as to be presented though the necessary diplomatic forms to the Supreme Constituent Cortes about to assemble. On this momentous question, in which the people both of Spain and the United States are so deeply interested, all our proceedings ought to be open, frank, and public. They should be of such a character as to challenge the approbation of the world. We firmly believe that, in the progress of human events, the time has arrived when the vital interests of Spain are as seriously involved in the sale, as those of the United States in the purchase of the island, and that the transaction will prove equally honorable to both nations. -

Chapter 13 the Coming of the Civil War

CHAPTER 13 THE COMING OF THE CIVIL WAR The American Nation: A History of the United States, 13th edition Carnes/Garraty Pearson Education, Inc., publishing as Longman © 2008 THE SLAVE POWER COMES NORTH n New fugitive slave law encouraged more white Southerners to try to recover escaped slaves n Many African Americans headed to Canada n Many Northerners refused to stand aside when people came n Many abolitionists interfered with slave captures n Such incidents exacerbated sectional feelings n Most white Northerners were not prepared to interfere with the enforcement of the Fugitive Slave Act themselves n 332 slaves were put on trial and 300 were returned to slavery without incident n Enforcing the law was increasingly difficult Pearson Education, Inc., publishing as Longman © 2008 Pearson Education, Inc., publishing as Longman © 2008 UNCLE TOM’S CABIN n Without any first hand knowledge of slavery, Harriet Beecher Stowe wrote novel in 1852 n Conscience had been roused by Fugitive Slave Act n Depended on abolitionist writers when gathering material for the book n Extremely successful n 10,000 copies were sold in a week n 300,000 in a year n It was translated into a dozen languages n Dramatized in countries throughout the world n Avoided selfrighteous accusatory tone of most abolitionist tracts and did not seek to convert readers to belief in racial equality Pearson Education, Inc., publishing as Longman © 2008 UNCLE TOM’S CABIN n Southern critics correctly noted that Stowe’s portrayal of plantation life was distorted and her slaves atypical n Most Northerners viewed Southern criticism as biased n No earlier American writer had viewed slaves as people Pearson Education, Inc., publishing as Longman © 2008 Pearson Education, Inc., publishing as Longman © 2008 DIVERSIONS ABROAD: The “Young America” Movement n “Young America” movement began to think of transmitting the dynamic, democratic U.S. -

Introduction the Spirit of Young America

Cambridge University Press 978-0-521-87564-6 - The Young America Movement and the Transformation of the Democratic Party, 1828-1861 Yonatan Eyal Excerpt More information Introduction The Spirit of Young America In 1853, New York writer and lecturer George William Curtis tried to put into words the elusive mindset known as Young America. Curtis attempted to define a concept that had many meanings in the antebellum United States, and in his speech he focused on its spirit of freshness and boldness. “Youth, or Young America, smiles at greatness,” he observed. It confidently expects to exceed and rival in greatness, “the noblest Roman of them all.” It says “well done” to Alexander, and pats Hannibal on the back; it smiles patronizingly on Julius Caesar, and will acknowledge Homer to be a good poet, if you insist upon it; and even admits that, at present, two and two make four. But it is secretly convinced that all these works of antiquity are only partial and incomplete affairs, not to be compared with what can be done in our day, and resolves that the time shall come when two and two shall make five.1 The Young American “prowls about Cuba,” he continued, “seeking how he may devour it, and sends Commodore Perry to Japan, with the very pleasant message that he is the sun, that the moon is his wife, and the earth their her- itage.” This assessment only barely exaggerated the quest for novelty that lay at the heart of the Young America ethos.2 Curtis’s contemporaries came to similar conclusions about Young America. -

CHAPTER THIRTEEN the IMPENDING CRISIS Objectives a Thorough Study of Chapter 13 Should Enable the Student to Understand 1

CHAPTER THIRTEEN THE IMPENDING CRISIS Objectives A thorough study of Chapter 13 should enable the student to understand 1. Manifest Destiny and its influence on the nation in the 1 840s. 2. The origin of the Republic of Texas and the controversy concerning its annexation by the United States. 3. The reasons the United States declared war on Mexico and how the Mexican War was fought to a successful conclusion. 4. The impact of the Wilmot Proviso on the sectional controversy. 5. The methods used to enact the Compromise of 1850 and its reception by the American people. 6. The role of the major political parties in the widening sectional split. 7. The part played by Stephen A. Douglas in the enactment of the Kansas-Nebraska Act and the effect of this act on his career and on the attitudes of Americans in all sections of the nation. 8. The impact of the Dred Scott decision on sectional attitudes and on the prestige of the Supreme Court. 9. The reasons for Abraham Lincoln’s victory in 1860 and the effect of his election on the sectional crisis. Main Themes 1. How the idea of Manifest Destiny influenced America and Americans during this period. 2. How the question of the expansion of slavery deepened divisions between the North and the South. 3. How the issue of slavery reshaped the American political-party system. Pertinent Questions LOOKING WESTWARD (340-346) 1. What was Manifest Destiny? What forces created it? 2. What was the “empire of liberty”? How was it to be achieved, and what doubts were raised about its desirability? 3. -

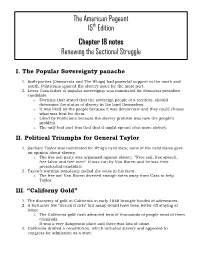

Edition Chapter 18 Notes Renewing the Sectional Struggle

The American Pageant th 15 Edition Chapter 18 notes Renewing the Sectional Struggle I. The Popular Sovereignty panache 1. Both parties (Democrats and The Whigs) had powerful support in the north and south. Politicians ignored the slavery issue for the most part. 2. Lewis Cass father of popular sovereignty was nominated for democrat president candidate. o Doctrine that stated that the sovereign people of a territory, should determine the status of slavery in the land themselves. o It was liked by the people because it was democratic and they could choose what was best for them. o Liked by Politicians because the slavery problem was now the people’s problem. o The only bad part was that that it might spread even more slavery. II. Political Triumphs for General Taylor 1. Zachary Taylor was nominated for Whig’s candidate; none of the candidates gave an opinion about slavery. o The free soil party was organized against slavery. “Free soil, free speech, free labor and free men”. It was run by Van Buren and he was their presidential candidate. 2. Taylor’s wartime popularity pulled the votes in his favor. o The free soil Van Buren diverted enough votes away from Cass to help Taylor. III. “Californy Gold” 1. The discovery of gold in California in early 1848 brought hordes of adventures. 2. A fortunate few “struck it rich” but many would have been better off staying at home. o The California gold rush attracted tens of thousands of people most of them criminals. It was a very dangerous place and there was lots of crime. -

A Dead Author to Be Resurrected: the Ambiguity of American Democracy in Herman Melville’S Pierre

5 The ALSJ Young Scholar Award for 2016 Shogo TANOKUCHI A Dead Author to Be Resurrected: The Ambiguity of American Democracy in Herman Melville’s Pierre Introduction erman Melville Crazy.” This was the notorious headline of the New York Day Book regarding Melvilleʼs seventh novel, Pierre: or, the “H Ambiguities (1852). Criticizing Pierre as a book of “the ravings and reveries of a madman,” the reviewer recommended that Melville be kept “stringently secluded from pen and ink” (Higgins and Parker 436). Contemporary reviewers viewed it as the book that led to Melvilleʼs death as an author. Melville experienced rejection and debt because of the harsh failure of his book and began to anonymously publish short stories.1 Along with the parallel between Melvilleʼs and Pierreʼs ruin as writers, scholars have conventionally interpreted the protagonistʼs death as a nihilistic end. F. O. Matthiessen notes that “nothing rises to take its place [“Pierreʼs world”] and assert continuity” (469) after his death in New York Cityʼs prison, “the Tombs.” Pierreʼs death seems to be pessimistic. After his encounter with Isabel Banford, who introduces herself as his half-blood sister, and the discovery of his fatherʼs adultery, the protagonist abandons his rich family and huge estate, Saddle Meadows. He becomes a writer to make a living with Isabel and an ill-fated maid, Delly, and to “deliver . miserably neglected Truth to the world” (283). Yet his The Journal of the American Literature Society of Japan, No. 15, February 2017. Ⓒ 2017 by The American Literature Society of Japan 6 Shogo TANOKUCHI aim cannot be achieved. -

William Kerrigan on Young America: the Flowering of Democracy in New York City

Edward L. Widmer. Young America: The Flowering of Democracy in New York City. New York: Oxford University Press, 1999. viii + 290 pp. $29.95, cloth, ISBN 978-0-19-510050-1. Reviewed by William T. Kerrigan Published on H-SHEAR (November, 1999) The sobriquet "Young America" appeared 1856, the Republicans would use it in John C. Fre‐ across the pages of magazines, newspapers, and mont's campaign. George Henry Evans, a champi‐ printed pamphlet speeches throughout the 1840s on of workers' rights and free land for the poor and 1850s. Its meaning was ambiguous and multi- adopted the slogan, as did George Francis Train, dimensional then, and subsequent scholarship on an ambitious international capitalist. A group of "The Young America movement" have been quite writers and literary critics centered in New York problematic. Efforts to define "Young America" as City employed the phrase in their efforts to pro‐ a movement have always reminded me of the fa‐ mote a distinctive American literature; aggressive ble of the fve blind mice crawling over an ele‐ expansionists who sought the acquisition of Cuba, phant. As each mouse explored a different part of Canada, and all of Mexico also yoked their cam‐ the Pachyderm's anatomy, each returned with a paigns to the Young American ox. Most of the his‐ radically different conclusion as to what the ani‐ torical writing on "Young America" has focused on mal was. References to "Young America" in histor‐ these last two manifestations. In Young America: ical literature seem to be almost as diverse as the The Flowering of Democracy in New York City, Ed‐ blind mice's conclusions. -

A New Nation Struggles to Find Its Footing

The decades leading to the United States Civil War – the Antebellum era – reflect 1829, David Walker (born as a free black in North Carolina) publishes The concept of Popular Sovereignty allowed settlers into those issues of slavery, party politics, expansionism, sectionalism, economics and ‘Appeal to the Colored Citizens of the World’ calling on slaves to revolt. territories to determine (by vote) if they would allow slavery within modernization. their boundaries. “Antebellum” – the phrase used in reference to the period of increasing 1831, William Lloyd Garrison publishes ‘The Liberator’ Advocated by Senator Stephen Douglas from Illinois. sectionalism which preceded the American Civil War. The abolitionist movement takes on a radical and religious element as The philosophy underpinning it dates to the English social it demands immediate emancipation. contract school of thought (mid-1600s to mid-1700s), represented Northwest Ordinance of 1787 by Thomas Hobbes, John Locke and Jean-Jacques Rousseau. The primary affect was to creation of the Northwest Territory as the first organized territory of the United States; it established the precedent by which the Antebellum: Increasing Sectional Divisions 1845, Frederick Douglass published his autobiography United States would expand westward across North America by admitting new The publishing of his life history empowers all abolitionists to states, rather than by the expansion of existing states. 1787-1860 (A Chronology, page 1 of 2) challenge the assertions of their pro-slave counterparts, in topics The banning of slavery in the territory had the effect of establishing the Ohio ranging from the ability of slaves to learn to questions of morality River as the boundary between free and slave territory in the region between 1831, Nat Turner’s Rebellion (slave uprising) and humanity.