Parkinson E Dieta.Pdf

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

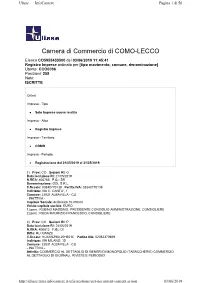

Camera Di Commercio Di COMO-LECCO

Ulisse — InfoCamere Pagina 1 di 56 Camera di Commercio di COMO-LECCO Elenco CO5955433500 del 03/06/2019 11:45:41 Registro Imprese ordinato per [tipo movimento, comune, denominazione] Utente: CCO0096 Posizioni: 258 Note: ISCRITTE Criteri: Impresa - Tipo Solo Imprese nuove iscritte Impresa - Albo Registro Imprese Impresa - Territorio COMO Impresa - Periodo Registrazione dal 01/05/2019 al 31/05/2019. 1) Prov: CO Sezioni RI: O Data iscrizione RI: 21/05/2019 N.REA: 400765 F.G.: SR Denominazione: GDL S.R.L. C.fiscale: 03840770139 Partita IVA: 03840770139 Indirizzo: VIA C. CANTU', 1 Comune: 22031 ALBAVILLA - CO - INATTIVA - Capitale Sociale: deliberato 10.000,00 Valuta capitale sociale: EURO 1) pers.: RUBINO MASSIMO, PRESIDENTE CONSIGLIO AMMINISTRAZIONE, CONSIGLIERE 2) pers.: RODA MAURIZIO FRANCESCO, CONSIGLIERE 2) Prov: CO Sezioni RI: P Data iscrizione RI: 24/05/2019 N.REA: 400812 F.G.: DI Ditta: HU XIANZE C.fiscale: HUXXNZ96L20H501C Partita IVA: 02062370669 Indirizzo: VIA MILANO, 15 Comune: 22031 ALBAVILLA - CO - INATTIVA - Attività: COMMERCIO AL DETTAGLIO DI GENERI DI MONOPOLIO (TABACCHERIE) COMMERCIO AL DETTAGLIO DI GIORNALI, RIVISTE E PERIODICI http://ulisse.intra.infocamere.it/ulis/gestione/get -document -content.action 03/ 06/ 2019 Ulisse — InfoCamere Pagina 2 di 56 1) pers.: HU XIANZE, TITOLARE FIRMATARIO 3) Prov: CO Sezioni RI: P - A Data iscrizione RI: 23/05/2019 N.REA: 400781 F.G.: DI Ditta: POLETTI GIORGIO C.fiscale: PLTGRG71T21C933L Partita IVA: 03838110132 Indirizzo: VIA ROMA, 83 Comune: 22032 ALBESE CON CASSANO - CO Data dom./accert.: 21/05/2019 Data inizio attività: 21/05/2019 Attività: INTONACATURA E TINTEGGIATURA C. Attività: 43.34 I / 43.34 A 1) pers.: POLETTI GIORGIO, TITOLARE FIRMATARIO 4) Prov: CO Sezioni RI: P - C Data iscrizione RI: 07/05/2019 N.REA: 400576 F.G.: DI Ditta: AZIENDA AGRICOLA LOLO DI BOVETTI FRANCESCO C.fiscale: BVTFNC84S01F205Q Partita IVA: 03839240136 Indirizzo: LOCALITA' RONDANINO SN Comune: 22024 ALTA VALLE INTELVI - CO Data inizio attività: 02/05/2019 Attività: ALLEVAMENTO DI EQUINI, COLTIVAZIONI FORAGGERE E SILVICOLTURA. -

Curriculum Vitae

CURRICULUM VITAE INFORMAZIONI PERSONALI nome CUFALO NICOLO’ data di nascita 02/01/1956 qualifica SEGRETARIO COMUNALE - FASCIA “A” (Abilitato per i Comuni con più di 65000 abitanti) incarico attuale SEGRETARIO COMUNALE DELLA SEDE CONVENZIONATA CERMENATE – VERTEMATE CON MINOPRIO numero telefonico 03188881213 e-mail [email protected] TITOLI DI STUDIO E PROFESSIONALI ED ESPERIENZE LAVORATIVE Titolo di studio Laurea in Giurisprudenza conseguita presso l’Università di Palermo nell’anno 1981 con il voto di 105/110 Altri titoli di studio e Diploma Ministero dell’Interno Corso di Studi per Aspiranti professionali Segretari Comunali conseguito presso l’Università di Milano nell’anno 1984 con il voto di 54/60 Esperienze Segretario Comunale F.R c/o Comune di Vescovana (PD). Classe 4^ dal 20.12.1984 professionali al 01.07.1985. Segretario Comunale F.R. c/o Comune di Barbona (PD) Classe 4^ dal 04.07.1985 al 05.08.1985. Segretario Comunale F.R. c/o Segreteria Consorziata Vezza d’Oglio – Incudine (BS) Clase 4^ dal 05.08.1985 al 07.10.1987 Segretario Comunale in ruolo c/o Segreteria Consorziata Santa Maria Rezzonico – Sant’Abbondio (COMO) Classe 4^ dal 08.10.1987 al 15.06.1992 Reggenza Segretria Consorziata Dongo – Stazzona (CO) Classe 3^ dal 10.12.1989. al 20.06.1991 e dal 24.04.1992 al 15.06.1992 Segretario Capo dal 09.10.1989. Segretario Capo titolare Segreteria Consorziata Dongo- Sant’Abbondio (CO) classe 3^ dal 16.06.1992 al 31.01.1997 Segretario Capo titolare Comune di Dongo (CO) Classe 3^ dal 01.02.1997 al 13.05.1998. -

From Brunate to Monte Piatto Easy Trail Along the Mountain Side , East from Como

1 From Brunate to Monte Piatto Easy trail along the mountain side , east from Como. From Torno it is possible to get back to Como by boat all year round. ITINERARY: Brunate - Monte Piatto - Torno WALKING TIME: 2hrs 30min ASCENT: almost none DESCENT: 400m DIFFICULTY: Easy. The path is mainly flat. The last section is a stepped mule track downhill, but the first section of the path is rather rugged. Not recommended in bad weather. TRAIL SIGNS: Signs to “Montepiatto” all along the trail CONNECTIONS: To Brunate Funicular from Como, Piazza De Gasperi every 30 minutes From Torno to Como boats and buses no. C30/31/32 ROUTE: From the lakeside road Lungo Lario Trieste in Como you can reach Brunate by funicular. The tram-like vehicle shuffles between the lake and the mountain village in 8 minutes. At the top station walk down the steps to turn right along via Roma. Here you can see lots of charming buildings dating back to the early 20th century, the golden era for Brunate’s tourism, like Villa Pirotta (Federico Frigerio, 1902) or the fountain called “Tre Fontane” with a Campari advertising bas-relief of the 30es. Turn left to follow via Nidrino, and pass by the Chalet Sonzogno (1902). Do not follow via Monte Rosa but instead walk down to the sportscentre. At the end of the football pitch follow the track on the right marked as “Strada Regia.” The trail slowly works its way down to the Monti di Blevio . Ignore the “Strada Regia” which leads to Capovico but continue straight along the flat path until you reach Monti di Sorto . -

Orari E Percorsi Della Linea Bus

Orari e mappe della linea bus C49 C49 Asso Visualizza In Una Pagina Web La linea bus C49 (Asso) ha 7 percorsi. Durante la settimana è operativa: (1) Asso: 06:55 - 18:35 (2) Asso FN: 06:10 - 17:35 (3) Como: 06:30 - 17:34 (4) Erba: 05:30 - 15:42 (5) Eupilio -> Lecco: 06:45 (6) Longone: 14:20 (7) Longone: 07:50 - 15:33 Usa Moovit per trovare le fermate della linea bus C49 più vicine a te e scoprire quando passerà il prossimo mezzo della linea bus C49 Direzione: Asso Orari della linea bus C49 33 fermate Orari di partenza verso Asso: VISUALIZZA GLI ORARI DELLA LINEA lunedì 06:55 - 18:35 martedì 06:55 - 18:35 Como - Stazione Trenord 3 Largo Giacomo Leopardi, Como mercoledì 06:55 - 18:35 Como - Popolo (Via Dante) giovedì 06:55 - 18:35 7 Piazza del Popolo, Como venerdì 06:55 - 18:35 Como - Via Dottesio 8/10 sabato 07:35 - 15:15 Via Luigi Dottesio, Como domenica Non in servizio Como - S. Martino (Extraurbana) 29 Via Briantea, Como Como - Crotto Del Sergente (Lora) Informazioni sulla linea bus C49 Como - Lora (Supermercato) Direzione: Asso Strada della Cappelletta, Como Fermate: 33 Durata del tragitto: 45 min Lipomo - Stabilimento Stacchini La linea in sintesi: Como - Stazione Trenord, Como - Popolo (Via Dante), Como - Via Dottesio 8/10, Como Lipomo - Bivio Paese (Rondò) - S. Martino (Extraurbana), Como - Crotto Del SPexSS342, Lipomo Sergente (Lora), Como - Lora (Supermercato), Lipomo - Stabilimento Stacchini, Lipomo - Bivio Tavernerio - Hotel Europa Paese (Rondò), Tavernerio - Hotel Europa, Tavernerio - S.S. Briantea (Incrocio), Albese - Viale Lombardia, Tavernerio - S.S. -

2021/22 Data: 25/06/2021 Ufficio Scolastico Provinciale Di: Como

POSTI DISPONIBILI DOPO LE OPERAZIONI DI MOBILITA' PERSONALE ATA ANNO SCOLASTICO: 2021/22 DATA: 25/06/2021 UFFICIO SCOLASTICO PROVINCIALE DI: COMO CODICE DENOMINAZIONE SCUOLA PROFILO CODICE AREADENOMINAZIONE AREA DENOMINAZIONE COMUNE DISPONIBILITA' SCUOLA COCT70000C PARINI - COMO CENTRO CITTA' ASSISTENTE AMMINISTRATIVO COMO 0 COCT70000C PARINI - COMO CENTRO CITTA' COLLABORATORE SCOLASTICO COMO 1 COCT701008 M. BUONARROTI ASSISTENTE AMMINISTRATIVO OLGIATE COMASCO 0 COCT701008 M. BUONARROTI COLLABORATORE SCOLASTICO OLGIATE COMASCO 2 COCT702004 MARELLI ASSISTENTE AMMINISTRATIVO CANTU' 1 COCT702004 MARELLI COLLABORATORE SCOLASTICO CANTU' 0 COCT70400QC.T.P. "REZIA" ASSISTENTE AMMINISTRATIVO MENAGGIO 1 COCT70400QC.T.P. "REZIA" COLLABORATORE SCOLASTICO MENAGGIO 0 COCT70500GC.T.P. PONTE LAMBRO ASSISTENTE AMMINISTRATIVO PONTE LAMBRO 1 COCT70500GC.T.P. PONTE LAMBRO COLLABORATORE SCOLASTICO PONTE LAMBRO 0 COCT70600B C.T.P. LOMAZZO ASSISTENTE AMMINISTRATIVO LOMAZZO 0 COCT70600B C.T.P. LOMAZZO COLLABORATORE SCOLASTICO LOMAZZO 0 COIC80100B I.C. SAN FEDELE ASSISTENTE AMMINISTRATIVO CENTRO VALLE INTELVI 0 COIC80100B I.C. SAN FEDELE COLLABORATORE SCOLASTICO TECNICO CENTRO VALLE INTELVI 0 (ADDETTO AZIENDE AGRARIE) COIC80100B I.C. SAN FEDELE COLLABORATORE SCOLASTICO CENTRO VALLE INTELVI 3 COIC80100B I.C. SAN FEDELE DIRETTORE DEI SERVIZI GENERALI E CENTRO VALLE INTELVI 1 AMMINISTRATIVI COIC802007 IST.COMPR. "A.ROSMINI" ASSISTENTE AMMINISTRATIVO PUSIANO 2 COIC802007 IST.COMPR. "A.ROSMINI" ASSISTENTE TECNICO AR02 ELETTRONICA ED ELETTROTECNICA PUSIANO 1 COIC802007 IST.COMPR. "A.ROSMINI" COLLABORATORE SCOLASTICO PUSIANO 5 COIC802007 IST.COMPR. "A.ROSMINI" DIRETTORE DEI SERVIZI GENERALI E PUSIANO 1 AMMINISTRATIVI COIC803003 I.C. ASSO ASSISTENTE AMMINISTRATIVO ASSO 1 COIC803003 I.C. ASSO COLLABORATORE SCOLASTICO TECNICO ASSO 0 (ADDETTO AZIENDE AGRARIE) COIC803003 I.C. ASSO COLLABORATORE SCOLASTICO ASSO 5 COIC803003 I.C. -

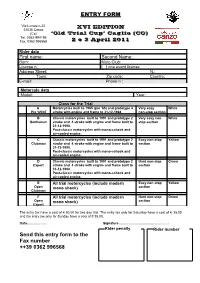

Send This Entry Form to the Fax Number ++39 0362 996568 How Reach the Trial in Caglio (CO)

ENTRY FORM Via Lunate n.22 22035 Canzo XVI EDITION (Co) ‘Old Trial Cup’ Caglio (CO) Tel. 0362-994198 Fax. 0362-996568 2 e 3 April 2011 Rider data First name: Second Name: Born: Moto Club: License n. [ ] one event license Address Street: N.: Town: Zip code: Country: E-mail: Phone n.: Motorcyle data Model: Year: Class for the Trial A Motorcycles built to 1965 (pre ’65) and prototype 4 Very easy White Pre ‘65/4T stroke with engine and frame to 31-12-1968 non-stop section B Classic motorcycles built to 1991 and prototype 2 Very easy non- White Gentlemen stroke and 4 stroke with engine and frame built to stop section 31-12-1990. Post-classic motorcycles with mono-schock and air-cooled engine. C Classic motorcycles built to 1991 and prototype 2 Easy non-stop Yellow Clubman stroke and 4 stroke with engine and frame built to section 31-12-1990. Post-classic motorcycles with mono-schock and air-cooled engine. D Classic motorcycles built to 1991 and prototype 2 Hard non-stop Green Expert stroke and 4 stroke with engine and frame built to section 31-12-1990. Post-classic motorcycles with mono-schock and air-cooled engine. E All trial motorcycles (include modern Easy non-stop Yellow Open mono shock) section Clubman F All trial motorcycles (include modern Hard non-stop Green Open mono shock) section Expert The entry tax have a cost of € 60,00 for two day trial. The entry tax only for Saturday have a cost of € 35,00 and the entry tax only for Sunday have a cost of € 35,00. -

Bocciata La Tangenziale Como «Meglio Potenziare La Ferrovia»

Bocciata la Tangenziale Como «Meglio potenziare la ferrovia» Capiago Intimiano. L'incontro organizzato da Fridays For Future sul secondo lotto della strada Il geologo Del Pero: «Scavare nel Monte Orfano creerebbe rischi di dissesto idrogeologico» Il secondo lotto della tangenziale di Como? No, grazie. È questo il riadattamento del classico slogan con cui, sabato sera, si è apertala serata organizzata del Fridays For Future Como gli studenti che ogni venerdì, sull'esempio di Greta Thunberg, scendono in piazza contro il clima in collaborazione con alcune associazioni ambientaliste e con il patrocinio del Comune di Capiago Intimiano. Per opporsi a un'autostrada, che, per qualcuno dei relatori, potenzialmente rappresenta un pericolo per il paesaggio e peri centri urbani: il tracciato, affermano, prima o poi rischia di diventare realtà. Questo, anche se al momento non c'è un progetto definitiva Proposta alternativa: potenziare la ferrovia Como-Lecco. Allarme cementificazione Platea attenta, alla nuova sede del Gabbiano di via Montecastello, con cittadini arrivati anche da altri Comuni del circondario. Gianni Del Pero, geologo dell'Università Milano Bicocca e presidente di WWF Insubria, ha affrontato il tema dell'entità dell'impatto ambientale.«Proprio per la posizione in cui siamo attorno al lago di Montorfano, scavare nel Monte Orfano piuttosto che effettuare dei lavori creerebbe rischio di dissesti idrogeologico ha affermato Inoltre, ci sarebbe una cementificazione indotta di capannoni attorno alle strade. A Grandate il paesaggio è stato stravolto per un'opera poco appetibile per gli utenti. A Lomazzo, dove c'era il bosco, adesso c'è uno svincolo. Il decreto salvaclima, tra le varie norme, dice che dal l° gennaio 2020, nelle aree interessate da criticità idraulica, cioè le nostre aree, non sono consentiti incrementi delle attuale quote di impermeabilizzazione del suolo. -

Orari E Percorsi Della Linea Treno

Orari e mappe della linea treno R16 Canzo-Asso Visualizza In Una Pagina Web La linea treno R16 (Canzo-Asso) ha 2 percorsi. Durante la settimana è operativa: (1) Canzo-Asso: 06:09 (2) Milano Cadorna: 19:03 - 20:33 Usa Moovit per trovare le fermate della linea treno R16 più vicine a te e scoprire quando passerà il prossimo mezzo della linea treno R16 Direzione: Canzo-Asso Orari della linea treno R16 19 fermate Orari di partenza verso Canzo-Asso: VISUALIZZA GLI ORARI DELLA LINEA lunedì Non in servizio martedì Non in servizio Milano Cadorna 16 Piazzale Luigi Cadorna, Milano mercoledì Non in servizio Milano Domodossola giovedì Non in servizio 9 Via Domodossola, Milano venerdì Non in servizio Milano Bovisa sabato Non in servizio 9 Piazza Emilio Alƒeri, Milano domenica 06:09 Milano Affori Cesano Maderno Seveso Informazioni sulla linea treno R16 Corso Guglielmo Marconi, Seveso Direzione: Canzo-Asso Fermate: 19 Meda Durata del tragitto: 82 min 12 Via Pace, Meda La linea in sintesi: Milano Cadorna, Milano Domodossola, Milano Bovisa, Milano Affori, Cesano Cabiate Maderno, Seveso, Meda, Cabiate, Mariano Comense, 1 Piazza della Libertà, Cabiate Carugo-Giussano, Arosio, Inverigo, Lambrugo- Lurago, Merone, Erba, Pontelambro-Castelmarte, Mariano Comense Caslino D'Erba, Canzo, Canzo-Asso Via Fabio Filzi, Mariano Comese Carugo-Giussano Arosio Piazza Chiesa, Arosio Inverigo Lambrugo-Lurago Merone Erba Piazza Padania, Erba Pontelambro-Castelmarte Viale Premuda, Ponte Lambro Caslino D'Erba Via Lambro, Caslino d'Erba Canzo Canzo-Asso Direzione: Milano Cadorna -

Linea CADORNA

linea CADORNA - SEVESO - CAMNAGO - ASSO Genere di treno S4 AUTO R S4 AUTO AUTO RS2S4 RS2S2 S4 AUTO R S4 R S4 AUTO S4 AUTO R S2/ S4 S2/ S4 AUTO R S2/ S4 S2/ S4 AUTO Numero del treno 11909 1609A 6611 10911 6613A 2913A 1613 1713 10915 6615 1717 6717 10917 2917A 1617 10919 621 10923 6923A 925 10925A 625 1727 10927 1729 929 10929A 631 1731 10931 1733 933 10933A Giorno di circolazione F6(4) F6(4) P(14) G(1) PG(7) P(14) F6(4) F5(3) G P(15) F5(3) P(12) G(1) P(16) F6(4) G G(1) G(1) P(6) G G(1) G F5(3) G(1) F5(3) G G(1) G(1) F5(3) G(1) F5(3) G G(1) [31] [36] [31] [36] [36] [31] [31] [31] [31] [31] [36] [31] [31] [36] [36] [36] [36] Nota commerciale [31] [31] [31] [36] [36] [36] [36] [38] [35] [38] [38] [35] [36] [35] [36] [35] [38] [35] [35] [38] [38] [38] [38] Classe 2 1-2 2 1-2 2 2 1-2 2 2 2 1-2 2 1-2 22 1-2 2 2 2 2 1-2 2 2 2 2 MILANO NORD 5.53 6.09 6.23 6.39 6.53 7.09 7.23 7.39 7.53 8.09 8.23 8.53 9.09 9.23 9.53 10.09 10.23 10.53 Milano Domodossola 5:56 6:12 6:26 6:42 6:56 7:12 7:26 7:42 7:56 8:12 8:26 8:56 9:12 9:26 9:56 10:12 10:26 10:56 Milano Bovisa a. -

031 673923 [email protected]

F ORMATO EUROPEO PER IL CURRICULUM VITAE INFORMAZIONI PERSONALI Nome CORTI VIVIANA Residenza Asso (CO) Telefono Ufficio: 031 673923 E-mail [email protected] Nazionalità Italiana Data e luogo di nascita 15/10/1957 – BOSISIO PARINI POSIZIONE LAVORATIVA ISTRUTTORE DIRETTIVO AMMINISTRATIVO RICOPERTA RESPONSABILE AREA SERVIZI DEMOGRAFICI E TRIBUTI ESPERIENZA LAVORATIVA • Date (da – a) DAL FEBBRAIO 1983 AD OGGI • Nome e indirizzo del datore di COMUNE DI ASSO – (Provincia di Como) lavoro Via Matteotti, 66 – 22033 Asso • Tipo di azienda o settore Ente Locale • Tipo di impiego ISTRUTTORE DIRETTIVO AMMINISTRATIVO categoria “D” p.e. D2 • Principali mansioni e responsabilità Responsabile dei Servizi Demografici e Tributi con posizione organizzativa (da dicembre 2015) Responsabile Servizio Demografico e Tributi (da gennaio 2005) Istruttore Amministrativo categoria “C” (da ottobre 2000) Area Economico-Finanziaria / Tributi / Servizi Demografici (Responsabile del Procedimento Servizi Demografici /Tributi) Collaboratore Amministrativo livello 5° (da ottobre 1993) Scrivana/Dattilografa livello 4° (da febbraio 1983) • Date (da – a) 1975 – 1977 • Nome e indirizzo del datore di Studio Legale Romanello – Erba (CO) lavoro Impiegata • Tipo di azienda o settore Studio legale / commercialista • Tipo di impiego Collaboratore d’ufficio – rapporti con i clienti • Principali mansioni e responsabilità Tenuta registri contabili artigiani e commercianti • Date (da – a) 1973 – 1974 • Nome e indirizzo del datore di S.M. Galvanotecnica S.p.A. – Canzo (CO) lavoro -

Milan and the Development and Dissemination of <I>Il Ballo Nobile

Quidditas Volume 20 Article 10 1999 Milan and the Development and Dissemination of Il ballo nobile: Lombardy as the Terpsichorean Treasury for Early Modern European Courts Katherine Tucker McGinnis University of North Carolina, Chapel Hill Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarsarchive.byu.edu/rmmra Part of the Comparative Literature Commons, History Commons, Philosophy Commons, and the Renaissance Studies Commons Recommended Citation McGinnis, Katherine Tucker (1999) "Milan and the Development and Dissemination of Il ballo nobile: Lombardy as the Terpsichorean Treasury for Early Modern European Courts," Quidditas: Vol. 20 , Article 10. Available at: https://scholarsarchive.byu.edu/rmmra/vol20/iss1/10 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by the Journals at BYU ScholarsArchive. It has been accepted for inclusion in Quidditas by an authorized editor of BYU ScholarsArchive. For more information, please contact [email protected], [email protected]. Milan and the Development and Dissemination of Il ballo nobile: Lombardy as the Terpsichorean Treasury for Early Modern European Courts Katherine Tucker McGinnis University of North Carolina, Chapel Hill E MOSCHE D’ITALIA IN UNA POPPA, Volando in Francia, per veder i ragni….”1 In these lines, titled “Di Pompeo Diabone,” the L Milanese artist and poet Giovanni Paolo Lomazzo celebrated the Italian dancing masters who, lured like flies to the web of the spider, served in the courts of France.2 In the sixteenth century there were many Italians in France, including a large number of influential and prosperous dancing masters.3 In spite of obvious connections with Florence via Catherine de’ Medici, the majority came from Lombardy, an area long considered the center of il ballo nobile, the formalized social dance that emphasized courtesy, courtliness, memory, and expertise. -

P.T. Infanzia E Primaria

DOCENTI DI SCUOLA PRIMARIA CON CONTRATTO PART-TIME DATA TIPO COGNOME E NOME TITOLARITA' ORE SITUAZIONE P.T. BIENNIO NASCITA POSTO Abate Francesca 24/12/1974 I.C. Rovellasca 18 Sostegno CONFERMA 2021/2023 Acquati Lidia 01/08/1959 I.C. Vertemate con Minoprio 18 comune 2020/2022 Acquistapace Grazia 22/08/1962 I.C. Asso 17 comune NUOVA 2021/2023 Alberti Manuela Piera 14/05/1976 I.C. Turate 12 comune NUOVA 2021/2023 Aliberti Carolina 16/06/1989 I.C. Cucciago 15 Comune CONFERMA 2021/2023 Amoretti Silvia 26/06/1974 I.C. Villaguardia 12 comune 2020/2022 Arcellaschi Anna 16/02/1960 I.C. Como Rebbio 18 comune 2020/2022 Armaleo Lucia 21/10/1989 I.C. Capiago Intimiano 18 Sostegno CONFERMA 2021/2023 Arnaboldi Chiara 29/07/1971 I.C. Bellagio 15 IRC VARIAZIONE 2020/2022 Baggio Tiziana 23/05/1957 I.C. Cantù 3 15 Comune CESSAZIONE 2021/2023 Baldini Anna 20/10/1959 I.C. Figino Serenza 15 Comune CESSAZIONE 2021/2023 Balestrini Paola 17/03/1963 I.C. Lomazzo 18 comune NUOVA 2021/2023 Baraglia Mariagrazia 05/10/1977 I.C. Gravedona 18 comune 2020/2022 Barindelli Donatella 14/09/1959 I.C. Bellagio 17 Comune CESSAZIONE Basilico Antonia Maria 14/02/1963 I.C. Rovellasca 18 Comune 2020/2022 Bedendo Isabella 15/06/1969 I.C. Capiago Intimiano 12 comune RIENTRA A T.P. Befi Mariagrazia 02/04/1977 I.C. Como Nord 13 comune 2020/2022 Bellini Maria Grazia 04/02/1962 I.C. Appiano Gentile 19 comune NUOVA 2021/2023 Benedetto Irene 14/01/1984 I.C.