Milan and the Development and Dissemination of <I>Il Ballo Nobile

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

EN ROCCHE EN.Pdf

Places to see and itineraries Where we are Bellaria Trento Igea Marina Milano Venezia Torino Bologna Oslo Helsinki Genova Ravenna Rimini Stoccolma Mosca Firenze Dublino Ancona Santarcangelo Perugia di Romagna Londra Amsterdam Varsavia Rimini Bruxelles Kijev Poggio Berni Roma Berlino Praga Vienna Bari Parigi Monaco Napoli Torriana Budapest Verucchio Milano Montebello Bucarest Rimini Riccione Madrid Cagliari Roma Catanzaro Ankara Coriano Talamello Repubblica Atene Palermo Novafeltria di San Marino Misano Adriatico Algeri Castelleale Tunisi Sant’Agata Feltria Maioletto San Leo Montescudo Agello Maiolo Montecolombo Cattolica Petrella Guidi Sassofeltrio San Clemente Gradara Maciano Gemmano Morciano San Giovanni fiume Conca di Romagna in Marignano Ponte Messa Pennabilli Casteldelci Monte AR Cerignone Montefiore Conca Saludecio Piacenza Molino Pietrarubbia Tavoleto Montegridolfo di Bascio Carpegna Macerata Mondaino Feltria Ferrara fiume Marecchia Sassocorvaro Parma Reggio Emilia Modena Rimini Mondaino Sismondo Castle Castle with Palaeontological museum Bologna Santarcangelo di Romagna Montegridolfo Ravenna Malatesta Fortress Fortified village Torriana/Montebello Montefiore Conca Forlì Fortress of the Guidi di Bagno Malatesta Fortress Cesena Verucchio Montescudo Rimini Malatesta Fortress Fortified village Castle of Albereto San Marino San Leo Fortress Montecolombo Fortified village Petrella Guidi Fortified village and castle ruins Monte Cerignone Fortress Sant’Agata Feltria Fortress Fregoso - museum Sassocorvaro Ubaldini Fortress Distances Pennabilli -

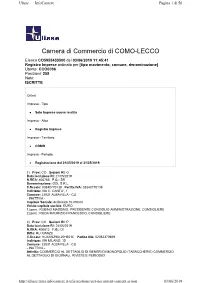

Camera Di Commercio Di COMO-LECCO

Ulisse — InfoCamere Pagina 1 di 56 Camera di Commercio di COMO-LECCO Elenco CO5955433500 del 03/06/2019 11:45:41 Registro Imprese ordinato per [tipo movimento, comune, denominazione] Utente: CCO0096 Posizioni: 258 Note: ISCRITTE Criteri: Impresa - Tipo Solo Imprese nuove iscritte Impresa - Albo Registro Imprese Impresa - Territorio COMO Impresa - Periodo Registrazione dal 01/05/2019 al 31/05/2019. 1) Prov: CO Sezioni RI: O Data iscrizione RI: 21/05/2019 N.REA: 400765 F.G.: SR Denominazione: GDL S.R.L. C.fiscale: 03840770139 Partita IVA: 03840770139 Indirizzo: VIA C. CANTU', 1 Comune: 22031 ALBAVILLA - CO - INATTIVA - Capitale Sociale: deliberato 10.000,00 Valuta capitale sociale: EURO 1) pers.: RUBINO MASSIMO, PRESIDENTE CONSIGLIO AMMINISTRAZIONE, CONSIGLIERE 2) pers.: RODA MAURIZIO FRANCESCO, CONSIGLIERE 2) Prov: CO Sezioni RI: P Data iscrizione RI: 24/05/2019 N.REA: 400812 F.G.: DI Ditta: HU XIANZE C.fiscale: HUXXNZ96L20H501C Partita IVA: 02062370669 Indirizzo: VIA MILANO, 15 Comune: 22031 ALBAVILLA - CO - INATTIVA - Attività: COMMERCIO AL DETTAGLIO DI GENERI DI MONOPOLIO (TABACCHERIE) COMMERCIO AL DETTAGLIO DI GIORNALI, RIVISTE E PERIODICI http://ulisse.intra.infocamere.it/ulis/gestione/get -document -content.action 03/ 06/ 2019 Ulisse — InfoCamere Pagina 2 di 56 1) pers.: HU XIANZE, TITOLARE FIRMATARIO 3) Prov: CO Sezioni RI: P - A Data iscrizione RI: 23/05/2019 N.REA: 400781 F.G.: DI Ditta: POLETTI GIORGIO C.fiscale: PLTGRG71T21C933L Partita IVA: 03838110132 Indirizzo: VIA ROMA, 83 Comune: 22032 ALBESE CON CASSANO - CO Data dom./accert.: 21/05/2019 Data inizio attività: 21/05/2019 Attività: INTONACATURA E TINTEGGIATURA C. Attività: 43.34 I / 43.34 A 1) pers.: POLETTI GIORGIO, TITOLARE FIRMATARIO 4) Prov: CO Sezioni RI: P - C Data iscrizione RI: 07/05/2019 N.REA: 400576 F.G.: DI Ditta: AZIENDA AGRICOLA LOLO DI BOVETTI FRANCESCO C.fiscale: BVTFNC84S01F205Q Partita IVA: 03839240136 Indirizzo: LOCALITA' RONDANINO SN Comune: 22024 ALTA VALLE INTELVI - CO Data inizio attività: 02/05/2019 Attività: ALLEVAMENTO DI EQUINI, COLTIVAZIONI FORAGGERE E SILVICOLTURA. -

4. Dressing and Portraying Isabella D'este

Cover Page The handle http://hdl.handle.net/1887/33552 holds various files of this Leiden University dissertation. Author: Dijk, Sara Jacomien van Title: 'Beauty adorns virtue' . Dress in portraits of women by Leonardo da Vinci Issue Date: 2015-06-18 4. Dressing and portraying Isabella d’Este Isabella d’Este, Marchioness of Mantua, has been thoroughly studied as a collector and patron of the arts.1 She employed the finest painters of her day, including Bellini, Mantegna and Perugino, to decorate her studiolo and she was an avid collector of antiquities. She also asked Leonardo to paint her likeness but though Leonardo drew a preparatory cartoon when he was in Mantua in 1499, now in the Louvre, he would never complete a portrait (fig. 5). Although Isabella is as well known for her love of fashion as her patronage, little has been written about the dress she wears in this cartoon. Like most of Leonardo’s female sitters, Isabella is portrayed without any jewellery. The only art historian to elaborate on this subject was Attilio Schiaparelli in 1921. Going against the communis opinio, he posited that the sitter could not be identified as Isabella d’Este. He considered the complete lack of ornamentation to be inappropriate for a marchioness and therefore believed the sitter to be someone of lesser status than Isabella.2 However, the sitter is now unanimously identified as Isabella d’Este.3 The importance of splendour was discussed at length in the previous chapter. Remarkably, Isabella is portrayed even more plainly than Cecilia Gallerani and the sitter of the Belle Ferronnière, both of whom are shown wearing at least a necklace (figs. -

Curriculum Vitae

CURRICULUM VITAE INFORMAZIONI PERSONALI nome CUFALO NICOLO’ data di nascita 02/01/1956 qualifica SEGRETARIO COMUNALE - FASCIA “A” (Abilitato per i Comuni con più di 65000 abitanti) incarico attuale SEGRETARIO COMUNALE DELLA SEDE CONVENZIONATA CERMENATE – VERTEMATE CON MINOPRIO numero telefonico 03188881213 e-mail [email protected] TITOLI DI STUDIO E PROFESSIONALI ED ESPERIENZE LAVORATIVE Titolo di studio Laurea in Giurisprudenza conseguita presso l’Università di Palermo nell’anno 1981 con il voto di 105/110 Altri titoli di studio e Diploma Ministero dell’Interno Corso di Studi per Aspiranti professionali Segretari Comunali conseguito presso l’Università di Milano nell’anno 1984 con il voto di 54/60 Esperienze Segretario Comunale F.R c/o Comune di Vescovana (PD). Classe 4^ dal 20.12.1984 professionali al 01.07.1985. Segretario Comunale F.R. c/o Comune di Barbona (PD) Classe 4^ dal 04.07.1985 al 05.08.1985. Segretario Comunale F.R. c/o Segreteria Consorziata Vezza d’Oglio – Incudine (BS) Clase 4^ dal 05.08.1985 al 07.10.1987 Segretario Comunale in ruolo c/o Segreteria Consorziata Santa Maria Rezzonico – Sant’Abbondio (COMO) Classe 4^ dal 08.10.1987 al 15.06.1992 Reggenza Segretria Consorziata Dongo – Stazzona (CO) Classe 3^ dal 10.12.1989. al 20.06.1991 e dal 24.04.1992 al 15.06.1992 Segretario Capo dal 09.10.1989. Segretario Capo titolare Segreteria Consorziata Dongo- Sant’Abbondio (CO) classe 3^ dal 16.06.1992 al 31.01.1997 Segretario Capo titolare Comune di Dongo (CO) Classe 3^ dal 01.02.1997 al 13.05.1998. -

From Brunate to Monte Piatto Easy Trail Along the Mountain Side , East from Como

1 From Brunate to Monte Piatto Easy trail along the mountain side , east from Como. From Torno it is possible to get back to Como by boat all year round. ITINERARY: Brunate - Monte Piatto - Torno WALKING TIME: 2hrs 30min ASCENT: almost none DESCENT: 400m DIFFICULTY: Easy. The path is mainly flat. The last section is a stepped mule track downhill, but the first section of the path is rather rugged. Not recommended in bad weather. TRAIL SIGNS: Signs to “Montepiatto” all along the trail CONNECTIONS: To Brunate Funicular from Como, Piazza De Gasperi every 30 minutes From Torno to Como boats and buses no. C30/31/32 ROUTE: From the lakeside road Lungo Lario Trieste in Como you can reach Brunate by funicular. The tram-like vehicle shuffles between the lake and the mountain village in 8 minutes. At the top station walk down the steps to turn right along via Roma. Here you can see lots of charming buildings dating back to the early 20th century, the golden era for Brunate’s tourism, like Villa Pirotta (Federico Frigerio, 1902) or the fountain called “Tre Fontane” with a Campari advertising bas-relief of the 30es. Turn left to follow via Nidrino, and pass by the Chalet Sonzogno (1902). Do not follow via Monte Rosa but instead walk down to the sportscentre. At the end of the football pitch follow the track on the right marked as “Strada Regia.” The trail slowly works its way down to the Monti di Blevio . Ignore the “Strada Regia” which leads to Capovico but continue straight along the flat path until you reach Monti di Sorto . -

Fra Sabba Da Castiglione: the Self-Fashioning of a Renaissance Knight Hospitaller”

“Fra Sabba da Castiglione: The Self-Fashioning of a Renaissance Knight Hospitaller” by Ranieri Moore Cavaceppi B.A., University of Pennsylvania 1988 M.A., University of North Carolina 1996 Thesis Submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the Degree of Doctor of Philosophy in the Department of Italian Studies at Brown University May 2011 © Copyright 2011 by Ranieri Moore Cavaceppi This dissertation by Ranieri Moore Cavaceppi is accepted in its present form by the Department of Italian Studies as satisfying the dissertation requirement for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy. Date Ronald L. Martinez, Advisor Recommended to the Graduate Council Date Evelyn Lincoln, Reader Date Ennio Rao, Reader Approved by the Graduate Council Date Peter M. Weber, Dean of the Graduate School iii CURRICULUM VITAE Ranieri Moore Cavaceppi was born in Rome, Italy on October 11, 1965, and moved to Washington, DC at the age of ten. A Fulbright Fellow and a graduate of the University of Pennsylvania, Ranieri received an M.A. in Italian literature from the University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill in 1996, whereupon he began his doctoral studies at Brown University with an emphasis on medieval and Renaissance Italian literature. Returning home to Washington in the fall of 2000, Ranieri became the father of three children, commenced his dissertation research on Knights Hospitaller, and was appointed the primary full-time instructor at American University, acting as language coordinator for the Italian program. iv PREFACE AND ACKNOWLEDGMENTS I deeply appreciate the generous help that I received from each member of my dissertation committee: my advisor Ronald Martinez took a keen interest in this project since its inception in 2004 and suggested many of its leading insights; my readers Evelyn Lincoln and Ennio Rao contributed numerous observations and suggestions. -

Nobility in Middle English Romance

Nobility in Middle English Romance Marianne A. Fisher A dissertation submitted for the degree of PhD Cardiff University 2013 Summary of Thesis: Postgraduate Research Degrees Student ID Number: 0542351 Title: Miss Surname: Fisher First Names: Marianne Alice School: ENCAP Title of Degree: PhD (English Literature) Full Title of Thesis Nobility in Middle English Romance Student ID Number: 0542351 Summary of Thesis Medieval nobility was a compound and fluid concept, the complexity of which is clearly reflected in the Middle English romances. This dissertation examines fourteen short verse romances, grouped by story-type into three categories. They are: type 1: romances of lost heirs (Degaré, Chevelere Assigne, Sir Perceval of Galles, Lybeaus Desconus, and Octavian); type 2: romances about winning a bride (Floris and Blancheflour, The Erle of Tolous, Sir Eglamour of Artois, Sir Degrevant, and the Amis– Belisaunt plot from Amis and Amiloun); type 3: romances of impoverished knights (Amiloun’s story from Amis and Amiloun, Sir Isumbras, Sir Amadace, Sir Cleges, and Sir Launfal). The analysis is based on contextualized close reading, drawing on the theories of Pierre Bourdieu. The results show that Middle English romance has no standard criteria for defining nobility, but draws on the full range on contemporary opinion; understandings of nobility conflict both between and within texts. Ideological consistency is seldom a priority, and the genre apparently serves neither a single socio-political agenda, nor a single socio-political group. The dominant conception of nobility in each romance is determined by the story-type. Romance type 1 presents nobility as inherent in the blood, type 2 emphasizes prowess and force of will, and type 3 concentrates on virtue. -

Italian Titles of Nobility

11/8/2020 Italian Titles of Nobility - A Concise, Accurate Guide to Nobiliary History, Tradition and Law in Italy until 1946 - Facts, no… Italian Titles of Nobility See also: Sicilian Heraldry & Nobility • Sicilian Genealogy • Books • Interview ©1997 – 2015 Louis Mendola Author's Note An article of this length can be little more than a precis. Apart from the presentation of the simplest facts, the author's intent is to provide accurate information, avoiding the bizarre ideas that color the study of the aristocracy. At best, this web page is a ready reference that offers a quick overview and a very concise bibliography; it is intended as nothing more. This page is published for the benefit of the historian, genealogist, heraldist, researcher or journalist – and all scientific freethinkers – in search of an objective, unbiased summary that does not seek (or presume) to insult their knowledge, intelligence or integrity. The study of the nobility and heraldry simply cannot exist without a sound basis in genealogical science. Genealogy is the only means of demonstrating familial lineage (ancestry), be it proven through documentation or DNA, be it aristocratic or humble. At 300 pages, the book Sicilian Genealogy and Heraldry considers the subject in far greater detail over several chapters, and while its chief focus is the Kingdom of Sicily, it takes into account the Kingdom of Italy (1861-1946) as well. That book includes chapters dedicated to, among other things, historiography, feudal law and proof standards. Like this web page, the book (you can peruse the table of contents, index and a few pages on Amazon's site) is the kind of reference and guide the author wishes were available when he began to study these fields seriously over thirty years ago. -

Is There a Printer's Copy of Gian Giorgio Trissino's Sophonisba?

Is There a Printer’s Copy of Gian Giorgio Trissino’s Sophonisba? Diego Perotti Abstract This essay examines the manuscript Additional 26873 housed in the British Library. After clarifying its physical features, it then explores various hypotheses as to its origins and its intended use. Finally, the essay collates the codex with Gian Giorgio Trissino’s first edition of the Sophonisba in order to establish the tragedy’s different drafts and the role of the manu- script in the scholarly edition’s plan. The manuscript classified as Additional 26873 (Hereafter La) is housed at the British Library in London and described in the online catalogue as follows: “Ital. Vellum; xvith cent. Injured by fire. Octavo. Giovanni Giorgio Trissino: Sophonisba: a tragedy”. A few details may be added. La is part of a larger collection comprising Additional 26789–26876: eighty-eight items composed in various languages (English, French, Italian, Latin, Portuguese, Spanish), many of which have been damaged to different degrees by fire and damp. The scribe has been identified as Ludovico degli Arrighi (1475–1527), the well-known calligrapher from Vicenza (Veneto, northern-east Italy) who later turned into a typographer, active between his hometown and Rome during the first quarter of the sixteenth century.1 Arrighi’s renowned handwriting, defined as corsivo lodoviciano (Ludovico’s italic), is a calligraphic italic based on the cancelleresca, well distinguished from the latter by the use of upright capitals characterized by long ascend- ers/descenders with curved ends, the lack of ties between characters, the greater space between transcriptional lines, and capital letters slightly 1. -

![List 3-2016 Accademia Della Crusca – Aldine Device 1) [BARDI, Giovanni (1534-1612)]](https://docslib.b-cdn.net/cover/5354/list-3-2016-accademia-della-crusca-aldine-device-1-bardi-giovanni-1534-1612-465354.webp)

List 3-2016 Accademia Della Crusca – Aldine Device 1) [BARDI, Giovanni (1534-1612)]

LIST 3-2016 ACCADEMIA DELLA CRUSCA – ALDINE DEVICE 1) [BARDI, Giovanni (1534-1612)]. Ristretto delle grandeze di Roma al tempo della Repub. e de gl’Imperadori. Tratto con breve e distinto modo dal Lipsio e altri autori antichi. Dell’Incruscato Academico della Crusca. Trattato utile e dilettevole a tutti li studiosi delle cose antiche de’ Romani. Posto in luce per Gio. Agnolo Ruffinelli. Roma, Bartolomeo Bonfadino [for Giovanni Angelo Ruffinelli], 1600. 8vo (155x98 mm); later cardboards; (16), 124, (2) pp. Lacking the last blank leaf. On the front pastedown and flyleaf engraved bookplates of Francesco Ricciardi de Vernaccia, Baron Landau, and G. Lizzani. On the title-page stamp of the Galletti Library, manuscript ownership’s in- scription (“Fran.co Casti”) at the bottom and manuscript initials “CR” on top. Ruffinelli’s device on the title-page. Some foxing and browning, but a good copy. FIRST AND ONLY EDITION of this guide of ancient Rome, mainly based on Iustus Lispius. The book was edited by Giovanni Angelo Ruffinelli and by him dedicated to Agostino Pallavicino. Ruff- inelli, who commissioned his editions to the main Roman typographers of the time, used as device the Aldine anchor and dolphin without the motto (cf. Il libro italiano del Cinquec- ento: produzione e commercio. Catalogo della mostra Biblioteca Nazionale Centrale, Roma 20 ottobre - 16 dicembre 1989, Rome, 1989, p. 119). Giovanni Maria Bardi, Count of Vernio, here dis- guised under the name of ‘Incruscato’, as he was called in the Accademia della Crusca, was born into a noble and rich family. He undertook the military career, participating to the war of Siena (1553-54), the defense of Malta against the Turks (1565) and the expedition against the Turks in Hun- gary (1594). -

Duchess and Hostage in Renaissance Naples: Letters and Orations

IPPOLITA MARIA SFORZA Duchess and Hostage in Renaissance Naples: Letters and Orations • Edited and translated by DIANA ROBIN and LYNN LARA WESTWATER Iter Press Toronto, Ontario Arizona Center for Medieval and Renaissance Studies Tempe, Arizona 2017 Sforza_book.indb 9 5/25/2017 10:47:22 AM Iter Press Tel: 416/978–7074 Email: [email protected] Fax: 416/978–1668 Web: www.itergateway.org Arizona Center for Medieval and Renaissance Studies Tel: 480/965–5900 Email: [email protected] Fax: 480/965–1681 Web: acmrs.org © 2017 Iter, Inc. and the Arizona Board of Regents for Arizona State University. All rights reserved. Printed in Canada. Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data Names: Sforza, Ippolita, 1445-1488, author. | Robin, Diana Maury, editor, translator. | Westwater, Lynn Lara, editor, translator. Title: Duchess and hostage in Renaissance Naples : letters and orations / Ippolita Maria Sforza ; edited and translated by Diana Robin, Lynn Lara Westwater. Description: Tempe, Arizona : Arizona Center for Medieval and Renaissance Studies ; Toronto, Ontario : Iter Press : Arizona Center for Medieval and Renaissance Studies, 2017. | Series: Medieval and Renaissance Texts and Studies ; 518 | Series: The Other Voice in Early Modern Europe. The Toronto Series, 55 | Includes bibliographical references and index. Identifiers: LCCN 2016059386 | ISBN 9780866985741 (pbk. : alk. paper) Subjects: LCSH: Sforza, Ippolita, 1445-1488—Correspondence. | Naples (Kingdom)—Court and courtiers—Correspondence. | Naples (Kingdom)—History—Spanish rule, 1442-1707--Sources. Classification: LCC DG848.112.S48 A4 2017 | DDC 945/.706092 [B]—dc23 LC record available at https://lccn.loc.gov/2016059386 Cover illustration: Pollaiuolo, Antonio del (1433-1498), Portrait of a Young Woman, ca. -

EUI Working Papers

DEPARTMENT OF HISTORY AND CIVILIZATION EUI Working Papers HEC 2010/02 DEPARTMENT OF HISTORY AND CIVILIZATION Moving Elites: Women and Cultural Transfers in the European Court System Proceedings of an International Workshop (Florence, 12-13 December 2008) Giulia Calvi and Isabelle Chabot (eds) EUROPEAN UNIVERSITY INSTITUTE , FLORENCE DEPARTMENT OF HISTORY AND CIVILIZATION Moving Elites: Women and Cultural Transfers in the European Court System Proceedings of an International Workshop (Florence, 12-13 December 2008) Edited by Giulia Calvi and Isabelle Chabot EUI W orking Paper HEC 2010/02 This text may be downloaded for personal research purposes only. Any additional reproduction for other purposes, whether in hard copy or electronically, requires the consent of the author(s), editor(s). If cited or quoted, reference should be made to the full name of the author(s), editor(s), the title, the working paper or other series, the year, and the publisher. ISSN 1725-6720 © 2010 Giulia Calvi and Isabelle Chabot (eds) Printed in Italy European University Institute Badia Fiesolana I – 50014 San Domenico di Fiesole (FI) Italy www.eui.eu cadmus.eui.eu Abstract The overall evaluation of the formation of political decision-making processes in the early modern period is being transformed by enriching our understanding of political language. This broader picture of court politics and diplomatic networks – which also relied on familial and kin ties – provides a way of studying the political role of women in early modern Europe. This role has to be studied taking into account the overlapping of familial and political concerns, where the intersection of women as mediators and coordinators of extended networks is a central feature of European societies.