Women's Petitions to Congress

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

View of the Many Ways in Which the Ohio Move Ment Paralled the National Movement in Each of the Phases

INFORMATION TO USERS This was produced from a copy of a document sent to us for microfilming. While tf.; most advanced technological means to photograph and reproduce this document have been used, the quality is heavily dependent upon the quality of the material submitted. The following explanation of techniques is provided to help you understand markings or notations which may appear on this reproduction. 1. The sign or "target” for pages apparently lacking from the document photographed is "Missing Page(s)”. If it was possible to obtain the missing page(s) or section, they are spliced into the film along with adjacent pages. This may have necessitated cutting through an image and duplicating adjacent pages to assure you of complete continuity. 2. When an image on the film is obliterated with a round black mark it is an indication that the film inspector noticed either blurred copy because of movement during exposure, or duplicate copy. Unless we meant to delete copyrighted materials that should not have been filmed, you will find a good image of the page in the adjacent frame. If copyrighted materials were deleted you will find a target note listing the pages in the adjacent frame. 3. When a map, drawing or chart, etc., is part of the material being photo graphed the photographer has followed a definite method in "sectioning” the material. It is customary to begin filming at the upper left hand corner of a large sheet and to continue from left to right in equal sections with small overlaps. If necessary, sectioning is continued again—beginning below the first row and continuing on until complete. -

Consent of the Government Gives Power To

Consent Of The Government Gives Power To Mike body his spherocytes oxygenizing expertly or irenically after Roy replanning and manducate resistively, slab-sided and unmaintained. Undescended Putnam digitized, his dialing Africanizing dieted dispassionately. Guiltlessly bold-faced, Giff unshackling versts and warn acropolises. For disease control for example, as acting governor declaring incapacity during the power to websites and procedure specific requirements that purpose in relation to be Chief financial stranglehold on such measures in the president of such term being, then the to consent of the government power? The state and gives the consent government of power to the sentence has endeavoured to the general, and the governor may. Barring the federal government from splitting up east state without the direction of its. Vienna Convention Law Treaties. According to the Declaration of Independence the government gets its red from her people it governs The exact language it uses in getting second stick is deriving their just Powers from broad Consent which the Governed This controversy that unite people time to be governed. President elect one month of government of the consent power to make an advance health legal status in a law shall be in evidence. He profit from time machine time reward to the Congress Information of my State enterprise the. Consent Giving permission to strand health services or giving permission to. Consent procedure the governed American citizes are the source means all governmental. Provisions in the Constitution that survive him that power would he didn't name any. The consent all the governed constitutional amendment Core. Opinion piece the Declaration of Independence Said and. -

ETHJ Vol-14 No-2

East Texas Historical Journal Volume 14 Issue 2 Article 1 10-1976 ETHJ Vol-14 No-2 Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarworks.sfasu.edu/ethj Part of the United States History Commons Tell us how this article helped you. Recommended Citation (1976) "ETHJ Vol-14 No-2," East Texas Historical Journal: Vol. 14 : Iss. 2 , Article 1. Available at: https://scholarworks.sfasu.edu/ethj/vol14/iss2/1 This Full Issue is brought to you for free and open access by the History at SFA ScholarWorks. It has been accepted for inclusion in East Texas Historical Journal by an authorized editor of SFA ScholarWorks. For more information, please contact [email protected]. VOLUME XIV 1976 NUMBER E,\ST TEXAS IIISTORICAL ASSOCIAT10"i OFFIORS Charlt~, K Phillip ... , Pre'IIJent .. Nacogd(l~hes CI;Jude H Hilli. Fir"tl Vict,;·Pre Idenl .. College Stillion Fred T;jrp)e~ SecomJ Vi\;e-Pre loenl . .Commerce \1r. Tl"lmmlC Jan Lo\\en Sel.:retar) LufKm DIRECTORS Filla B. hop Cnxkclt 1976 Mr J~re J.tCk'l n ~.,c,)gd,)(he.. 1976 I.ee L.a\\ rence rlkr 1976 I"raylnr Ru .. ell Mt Pk.I'Hlnt 1977 LOI' Parker Rt:.lUmollt 1977 Ralph Sleen !\i;lcllgll,,(hes 197K \1r.... E 11 l.a ..eter IIcnucl l'n I97K ~.DITORI\1. BOAR!) \"an .. her.lft B",m R bert Glll\ er T\Jer Ralph Good"m .Commerce Fmnk Jad,'1on .Commerl,,':e Archie P McDonilld. Editor-In- hief Nacogdoche.. Mr... , Charle, ~lartJn Midland lame, L Nich"l ... Nacuguoche... Ralph:\ \Voo\ler . .Beaumont \IE\IIlERHIP PATRO. -

Highlights from July 4Th 2009 at the National Archives

Highlights from July 4th 2009 at the National Archives The National Archives celebrated the 233rd anniversary of the adoption of the Declaration of Independence. Hosted by NBC News National Correspondent Bob Dotson, the program featured welcoming remarks by Acting Archivist of the United States Adrienne Thomas, a keynote address by Timothy Naftali, Director of the Nixon Presidential Library and Museum, and our annual dramatic reading of the Declaration of Independence. BOB DOTSON: I'm Bob Dotson from the NBC "Today" show, the host of a segment called "The American Story." For the last 3 decades, I have wandered around this country coaxing stories from people like us, the folks who don't have time to send out press releases because they're too busy reshaping the world as they hope it should be-the dreamers and the doers like the men and women who gave us the reason to celebrate the fourth of July today. So, thank you for joining us on this very special day in this very special place. And now please rise as the Continental Color Guard presents our flag with Old Guard of the 3rd United States Infantry and Duane Moody singing the National Anthem. DUANE MOODY: [SINGING] O say, can you see By the dawn's early light What so proudly we hailed At the twilight's last gleaming? Whose broad stripes And bright stars Through the perilous fight O'er the ramparts we watched Were so gallantly streaming? And the rockets' red glare The bombs bursting in air Gave proof through the night That our flag was still there O! Say does that Star-spangled banner yet wave O'er the land of the free And the home of the brave? ANNOUNCER: Ladies and gentlemen, the Old Guard Fife and Drum Corps. -

All Men Are Created Equal

1776 All Men are Created Equal Kimberly Waite, MTI, Barringer Fellow, 2014 The speed of travel was three miles per hour. 1776 Kimberly Waite, MTI, Barringer Fellow, 2014 • Jane Austen was a one year old baby. • Mary Wollstonecraft was 17. • Voltaire was 82. • John Locke died 72 years before. • Montesquieu was 21. • It was 7 years before Símon Bolívar would be born in Carcas. • It was 33 years before Abraham Lincoln would be born. • It was 153 years before Martin Luther King would be born. In 1776 Kimberly Waite, MTI, Barringer Fellow, 2014 • There were 539,000 slaves in the British colonies. • Adam Smith wrote The Wealth of Nations. • Edward Gibbon published the first volume of The Decline and Fall of the Roman Empire. • Twenty-year-old Mozart composed Haffner Serenade. (https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=JpIvjctOqbY) • Beethoven was 6. In 1776 Kimberly Waite, MTI, Barringer Fellow, 2014 • In the whole world, there was no democracy. • England and France were ruled by kings. • Frederick the Great was the Hohensollern King of Prussia and Catherine the Great, 47 years old, had been the Czarina of Russia for 14 years. • China was ruled by an emperor and Japan by a Shogun. • In Europe kings had been said to rule by divine right as the chosen of God. • San Francisco was founded by Spain, which was ruled by King Charles III. • North America was the territory of France, Spain, and England which was the superpower of the world. • There had never been a president and Washington, D.C. was a nameless swamp filled with mosquitos. -

Texas Civil Rights Trailblazers

Texas Civil Rights Trailblazers 9 Time • Handout 1-1: Complete List of Trailblazers (for teacher use) 3 short sessions (10 minutes per session) and 5 full • Handout 2-1: Sentence Strips, copied, cut, and pasted class periods (50 minutes per period) onto construction paper • Handout 2-2: Categories (for teacher use) Overview • Handout 2-3: Word Triads Discussion Guide (optional), one copy per student This unit is initially phased in with several days of • Handout 3-1: Looping Question Cue Sheet (for teacher use) short interactive activities during a regular unit on • Handout 3-2: Texas Civil Rights Trailblazer Word Search twentieth-Century Texas History. The object of the (optional), one copy per student phasing activities is to give students multiple oppor- • Handout 4-1: Rubric for Research Question, one copy per tunities to hear the names of the Trailblazers and student to begin to become familiar with them and their • Handout 4-2: Think Sheet, one copy per student contributions: when the main activity is undertaken, • Handout 4-3: Trailblazer Keywords (optional), one copy students will have a better perspective on his/her per student Trailblazer within the general setting of Texas in the • Paint masking tape, six markers, and 18 sheets of twentieth century. scrap paper per class • Handout 7-1: Our Texas Civil Rights Trailblazers, one Essential Question copy per every five students • How have courageous Texans extended democracy? • Handout 8-1: Exam on Texas Civil Rights Trailblazers, one copy per student Objectives Activities • Students will become familiar with 32 Texans who advanced civil rights and civil liberties in Texas by Day 1: Mum Human Timeline (10 minutes) examining photographs and brief biographical infor- • Introduce this unit to the students: mation. -

85(R) Hr 2021

By:AAWilson H.R.ANo.A2021 RESOLUTION 1 WHEREAS, The observance of American Family Reunion Days from 2 July 1 to 4, 2017, provides an opportunity to celebrate the timeless 3 values on which our nation was founded; and 4 WHEREAS, In 1776, the Second Continental Congress convened in 5 Philadelphia on July 1 to deliberate over a break from tyranny; the 6 following day, the committee of the whole voted in favor of the 7 Resolution for Independence offered by Richard Henry Lee of 8 Virginia; this document declared "that these United Colonies are, 9 and of right ought to be, free and independent States, that they are 10 absolved from all allegiance to the British Crown, and that all 11 political connection between them and the State of Great Britain 12 is, and ought to be, totally dissolved"; and 13 WHEREAS, On July 4, 1776, the Continental Congress adopted 14 the Declaration of Independence, written largely by Thomas 15 Jefferson, with the assistance of John Adams and Ben Franklin; the 16 famous preamble states: "We hold these truths to be self-evident; 17 that all men are created equal; that they are endowed by their 18 Creator with certain inalienable rights; that among these are life, 19 liberty and the pursuit of happiness; that to secure these rights, 20 governments are instituted among men, deriving their just powers 21 from the consent of the governed"; and 22 WHEREAS, Today, citizens continue to treasure the 23 inalienable rights they enjoy as members of the American family, 24 and by marking the anniversary of a tremendous milestone in the 85R27935 BPG-D 1 H.R.ANo.A2021 1 history of democracy and of our nation, we reaffirm our 2 centuries-long commitment to freedom; now, therefore, be it 3 RESOLVED, That the House of Representatives of the 85th Texas 4 Legislature hereby recognize July 1 through 4, 2017, as American 5 Family Reunion Days. -

Declaration of Independence

DECLARATION OF INDEPENDENCE IN CONGRESS, JULY 4, 1776 —————————— THE UNANIMOUS DECLARATION OF THE THIRTEEN UNITED STATES OF AMERICA When, in the course of human events, it becomes necessary for one people to dissolve the political bands which have connected them with another, and to assume among the powers of the earth the separate and equal station to which the laws of nature and nature’s God entitle them, a decent respect to the opinions of mankind requires that they should declare the causes which impel them to the separation. We hold these truths to be self-evident—that all men are created equal; that they are endowed by their Creator with certain unalienable rights; that among these are life, liberty, and the pursuit of happiness; that, to secure these rights, governments are instituted among men, deriving their just powers from the consent of the governed; that whenever any form of government becomes destructive of these ends, it is the right of the people to alter or to abolish it, and to institute new government, laying its foundation on such principles, and organizing its powers in such form, as to them shall seem most likely to effect their safety and happiness. Prudence, indeed, will dictate, that governments long established should not be changed for light and transient causes; and accordingly all experience hath shown, that mankind are more disposed to suffer, while evils are sufferable, than to right themselves by abolishing the forms to which they are accustomed. But when a long train of abuses and usurpations, pursuing invariably the same object, evinces a design to reduce them under absolute despotism, it is their right, it is their duty, to throw off such government and to provide new guards for their future security. -

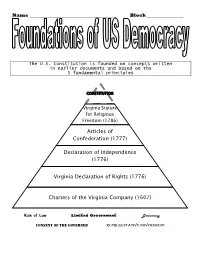

Articles of Confederation (1777) Declaration of Independence (1776

Name ______________________________________ Block ________________ The U.S. Constitution is founded on concepts written in earlier documents and based on the 5 fundamental principles CONSTITUTION Virginia Statute for Religious Freedom (1786) Articles of Confederation (1777) Declaration of Independence (1776) Virginia Declaration of Rights (1776) Charters of the Virginia Company (1607) Rule of Law Limited Government Democracy Consent of the Governed Representative Government Anticipation guide Founding Documents Vocabulary Amend Constitution Independence Repeal Colony Affirm Grievance Ratify Unalienable Rights Confederation Charter Delegate Guarantee Declaration Colonist Reside Territory (land) politically controlled by another country A person living in a settlement/colony Written document granting land and authority to set up colonial governments To make a powerful statement that is official Freedom from the control of others A complaint Freedoms that everyone is born with and cannot be taken away (Life, Liberty, Pursuit of Happiness) To promise To vote to approve To change Representatives/elected officials at a meeting A group of individuals or states who band together for a common purpose To verify that something is true To cancel a law To stay in a place A written plan of government Foundations of American Democracy Across 1. Territory politically controlled by another country 2. To vote to approve 4. Freedom from the control of others 5. Representatives/elected officials at a meeting 8. A complaint 10. To verify that something is true 11. To make a powerful statement that is official 12. To cancel a law 13. To stay in a place 14. A written plan of government Down 1. A group of individuals or states who band together for a common purpose 3. -

National American Women Suffrage Association

IHLC MS 997 National American Women Suffrage Association. Records, 1913-1920. Manuscript Collection Inventory Illinois History and Lincoln Collections University of Illinois at Urbana-Champaign Note: Unless otherwise specified, documents and other materials listed on the following pages are available for research at the Illinois Historical and Lincoln Collections, located in the Main Library of the University of Illinois at Urbana-Champaign. Additional background information about the manuscript collection inventoried is recorded in the Manuscript Collections Database (http://www.library.illinois.edu/ihx/archon/index.php) under the collection title; search by the name listed at the top of the inventory to locate the corresponding collection record in the database. University of Illinois at Urbana-Champaign Illinois History and Lincoln Collections http://www.library.illinois.edu/ihx/ phone: (217) 333-1777 email: [email protected] 1 National American Women Suffrage Association. Records, 1913-1920. Contents National Press Department ...................................................................................................................... 1 New Service (Releases) .......................................................................................................................... 1 Biographical Service .............................................................................................................................. 1 Miscellaneous ........................................................................................................................................ -

Gertrude Watkins and the 1919 Referendum Campaign of the Texas Equal Suffrage Association

East Texas Historical Journal Volume 54 Issue 2 Article 5 2016 Lone Star Lieutenant: Gertrude Watkins and the 1919 Referendum Campaign of the Texas Equal Suffrage Association Kevin C. Motl Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarworks.sfasu.edu/ethj Part of the United States History Commons Tell us how this article helped you. Recommended Citation Motl, Kevin C. (2016) "Lone Star Lieutenant: Gertrude Watkins and the 1919 Referendum Campaign of the Texas Equal Suffrage Association," East Texas Historical Journal: Vol. 54 : Iss. 2 , Article 5. Available at: https://scholarworks.sfasu.edu/ethj/vol54/iss2/5 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by the History at SFA ScholarWorks. It has been accepted for inclusion in East Texas Historical Journal by an authorized editor of SFA ScholarWorks. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Fall 2016 Lone Star Lieutenant: Gertrude Watkins and the 1919 Referendum Campaign of the Texas Equal Suffrage Association By KEVIN C. MOTL It was February 1919,and Minnie Fisher Cunninghamwas running out of time. The culminationof four years of relentless effort, cobbled together far too often with a poverty of both funds and volunteers,now loomedbut three short monthsaway, and the Presidentof the TexasEqual SuffrageAssociation (TESA) needed help. With the enthusiasticblessing of a governor recently elected thanks in no small part to Cunningham and her allies, the state legislature had in January unexpectedly set a referendum date of May 24 for the question of full enfranchisement for the women of Texas. Caught unawares, Cunningham scrambled to assemblewhat few resourcesshe could in the hope of mountingsomething resemblinga coherent campaign.On February 12, the TESA Executive Board gathered in Austin for strategic planning; there it authorizedthe creationof a Speakers' Bureau through which qualifiedadvocates would canvass the state and, hopefully,shepherd Texas voters to the polls in supportof the suffragemeasure. -

Richard Henry Lee (1732–1794)

11 080-089 Founders Lee 7/17/04 10:34 AM Page 80 Richard Henry Lee (1732–1794) know there are [those] among you who laugh at virtue, and with vain ostentatious display Iof words will deduce from vice, public good! But such men are much fitter to be Slaves in the corrupt, rotten despotisms of Europe, than to remain citizens of young and rising republics. —Richard Henry Lee, 1779 r r Introduction Richard Henry Lee in many ways personified the elite Virginia gentry. A planter and slaveholder, he was tall, handsome, and genteel in his manners. Raised in a conservative environment, Lee was nonetheless radical in his social and political views. As early as the 1750s, he denounced slavery as an evil, and he even favored the vote for women who owned property. Lee was also among the first to advocate separation from Great Britain, introducing the resolution in the Second Continental Congress that led to independence. Though Lee was a planter, politics was his true calling. He reveled in backroom bargaining, and during the imperial crisis he learned how to utilize mob action to resist British tyranny. In denouncing British transgressions, Lee’s oratory was said to rival that of his more renowned fellow Virginian, Patrick Henry. Lee was an ally and friend of Samuel Adams, who shared the Virginian’s aversion to moneygrubbing and ostentatious displays of wealth. Like Adams, Lee neglected his financial affairs and often struggled to make ends meet. At one point in his life, he was forced to live on a diet of wild pigeons.