The Consent of the Governed.Pdf

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Hayek's the Constitution of Liberty

Hayek’s The Constitution of Liberty Hayek’s The Constitution of Liberty An Account of Its Argument EUGENE F. MILLER The Institute of Economic Affairs contenTs The author 11 First published in Great Britain in 2010 by Foreword by Steven D. Ealy 12 The Institute of Economic Affairs 2 Lord North Street Summary 17 Westminster Editorial note 22 London sw1p 3lb Author’s preface 23 in association with Profile Books Ltd The mission of the Institute of Economic Affairs is to improve public 1 Hayek’s Introduction 29 understanding of the fundamental institutions of a free society, by analysing Civilisation 31 and expounding the role of markets in solving economic and social problems. Political philosophy 32 Copyright © The Institute of Economic Affairs 2010 The ideal 34 The moral right of the author has been asserted. All rights reserved. Without limiting the rights under copyright reserved above, no part of this publication may be reproduced, stored or introduced into a PART I: THE VALUE OF FREEDOM 37 retrieval system, or transmitted, in any form or by any means (electronic, mechanical, photocopying, recording or otherwise), without the prior written permission of both the copyright owner and the publisher of this book. 2 Individual freedom, coercion and progress A CIP catalogue record for this book is available from the British Library. (Chapters 1–5 and 9) 39 isbn 978 0 255 36637 3 Individual freedom and responsibility 39 The individual and society 42 Many IEA publications are translated into languages other than English or are reprinted. Permission to translate or to reprint should be sought from the Limiting state coercion 44 Director General at the address above. -

American Civil Associations and the Growth of American Government: an Appraisal of Alexis De Tocqueville’S Democracy in America (1835-1840) Applied to Franklin D

City University of New York (CUNY) CUNY Academic Works All Dissertations, Theses, and Capstone Projects Dissertations, Theses, and Capstone Projects 2-2017 American Civil Associations and the Growth of American Government: An Appraisal of Alexis de Tocqueville’s Democracy in America (1835-1840) Applied to Franklin D. Roosevelt's New Deal and the Post-World War II Welfare State John P. Varacalli The Graduate Center, City University of New York How does access to this work benefit ou?y Let us know! More information about this work at: https://academicworks.cuny.edu/gc_etds/1828 Discover additional works at: https://academicworks.cuny.edu This work is made publicly available by the City University of New York (CUNY). Contact: [email protected] AMERICAN CIVIL ASSOCIATIONS AND THE GROWTH OF AMERICAN GOVERNMENT: AN APPRAISAL OF ALEXIS DE TOCQUEVILLE’S DEMOCRACY IN AMERICA (1835- 1840) APPLIED TO FRANKLIN D. ROOSEVELT’S NEW DEAL AND THE POST-WORLD WAR II WELFARE STATE by JOHN P. VARACALLI A master’s thesis submitted to the Graduate Program in Liberal Studies in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Master of Arts, The City University of New York 2017 © 2017 JOHN P. VARACALLI All Rights Reserved ii American Civil Associations and the Growth of American Government: An Appraisal of Alexis de Tocqueville’s Democracy in America (1835-1840) Applied to Franklin D. Roosevelt’s New Deal and the Post World War II Welfare State by John P. Varacalli The manuscript has been read and accepted for the Graduate Faculty in Liberal Studies in satisfaction of the thesis requirement for the degree of Master of Arts ______________________ __________________________________________ Date David Gordon Thesis Advisor ______________________ __________________________________________ Date Elizabeth Macaulay-Lewis Acting Executive Officer THE CITY UNIVERSITY OF NEW YORK iii ABSTRACT American Civil Associations and the Growth of American Government: An Appraisal of Alexis de Tocqueville’s Democracy in America (1835-1840) Applied to Franklin D. -

Mill's "Very Simple Principle": Liberty, Utilitarianism And

MILL'S "VERY SIMPLE PRINCIPLE": LIBERTY, UTILITARIANISM AND SOCIALISM MICHAEL GRENFELL submitted for degree of Ph.D. London School of Economics and Political Science UMI Number: U048607 All rights reserved INFORMATION TO ALL USERS The quality of this reproduction is dependent upon the quality of the copy submitted. In the unlikely event that the author did not send a complete manuscript and there are missing pages, these will be noted. Also, if material had to be removed, a note will indicate the deletion. Dissertation Publishing UMI U048607 Published by ProQuest LLC 2014. Copyright in the Dissertation held by the Author. Microform Edition © ProQuest LLC. All rights reserved. This work is protected against unauthorized copying under Title 17, United States Code. ProQuest LLC 789 East Eisenhower Parkway P.O. Box 1346 Ann Arbor, Ml 48106-1346 I H^S £ S F 6SI6 ABSTRACT OF THESIS MILL'S "VERY SIMPLE PRINCIPLE'*: LIBERTY. UTILITARIANISM AND SOCIALISM 1 The thesis aims to examine the political consequences of applying J.S. Mill's "very simple principle" of liberty in practice: whether the result would be free-market liberalism or socialism, and to what extent a society governed in accordance with the principle would be free. 2 Contrary to Mill's claims for the principle, it fails to provide a clear or coherent answer to this "practical question". This is largely because of three essential ambiguities in Mill's formulation of the principle, examined in turn in the three chapters of the thesis. 3 First, Mill is ambivalent about whether liberty is to be promoted for its intrinsic value, or because it is instrumental to the achievement of other objectives, principally the utilitarian objective of "general welfare". -

Consent of the Government Gives Power To

Consent Of The Government Gives Power To Mike body his spherocytes oxygenizing expertly or irenically after Roy replanning and manducate resistively, slab-sided and unmaintained. Undescended Putnam digitized, his dialing Africanizing dieted dispassionately. Guiltlessly bold-faced, Giff unshackling versts and warn acropolises. For disease control for example, as acting governor declaring incapacity during the power to websites and procedure specific requirements that purpose in relation to be Chief financial stranglehold on such measures in the president of such term being, then the to consent of the government power? The state and gives the consent government of power to the sentence has endeavoured to the general, and the governor may. Barring the federal government from splitting up east state without the direction of its. Vienna Convention Law Treaties. According to the Declaration of Independence the government gets its red from her people it governs The exact language it uses in getting second stick is deriving their just Powers from broad Consent which the Governed This controversy that unite people time to be governed. President elect one month of government of the consent power to make an advance health legal status in a law shall be in evidence. He profit from time machine time reward to the Congress Information of my State enterprise the. Consent Giving permission to strand health services or giving permission to. Consent procedure the governed American citizes are the source means all governmental. Provisions in the Constitution that survive him that power would he didn't name any. The consent all the governed constitutional amendment Core. Opinion piece the Declaration of Independence Said and. -

Highlights from July 4Th 2009 at the National Archives

Highlights from July 4th 2009 at the National Archives The National Archives celebrated the 233rd anniversary of the adoption of the Declaration of Independence. Hosted by NBC News National Correspondent Bob Dotson, the program featured welcoming remarks by Acting Archivist of the United States Adrienne Thomas, a keynote address by Timothy Naftali, Director of the Nixon Presidential Library and Museum, and our annual dramatic reading of the Declaration of Independence. BOB DOTSON: I'm Bob Dotson from the NBC "Today" show, the host of a segment called "The American Story." For the last 3 decades, I have wandered around this country coaxing stories from people like us, the folks who don't have time to send out press releases because they're too busy reshaping the world as they hope it should be-the dreamers and the doers like the men and women who gave us the reason to celebrate the fourth of July today. So, thank you for joining us on this very special day in this very special place. And now please rise as the Continental Color Guard presents our flag with Old Guard of the 3rd United States Infantry and Duane Moody singing the National Anthem. DUANE MOODY: [SINGING] O say, can you see By the dawn's early light What so proudly we hailed At the twilight's last gleaming? Whose broad stripes And bright stars Through the perilous fight O'er the ramparts we watched Were so gallantly streaming? And the rockets' red glare The bombs bursting in air Gave proof through the night That our flag was still there O! Say does that Star-spangled banner yet wave O'er the land of the free And the home of the brave? ANNOUNCER: Ladies and gentlemen, the Old Guard Fife and Drum Corps. -

All Men Are Created Equal

1776 All Men are Created Equal Kimberly Waite, MTI, Barringer Fellow, 2014 The speed of travel was three miles per hour. 1776 Kimberly Waite, MTI, Barringer Fellow, 2014 • Jane Austen was a one year old baby. • Mary Wollstonecraft was 17. • Voltaire was 82. • John Locke died 72 years before. • Montesquieu was 21. • It was 7 years before Símon Bolívar would be born in Carcas. • It was 33 years before Abraham Lincoln would be born. • It was 153 years before Martin Luther King would be born. In 1776 Kimberly Waite, MTI, Barringer Fellow, 2014 • There were 539,000 slaves in the British colonies. • Adam Smith wrote The Wealth of Nations. • Edward Gibbon published the first volume of The Decline and Fall of the Roman Empire. • Twenty-year-old Mozart composed Haffner Serenade. (https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=JpIvjctOqbY) • Beethoven was 6. In 1776 Kimberly Waite, MTI, Barringer Fellow, 2014 • In the whole world, there was no democracy. • England and France were ruled by kings. • Frederick the Great was the Hohensollern King of Prussia and Catherine the Great, 47 years old, had been the Czarina of Russia for 14 years. • China was ruled by an emperor and Japan by a Shogun. • In Europe kings had been said to rule by divine right as the chosen of God. • San Francisco was founded by Spain, which was ruled by King Charles III. • North America was the territory of France, Spain, and England which was the superpower of the world. • There had never been a president and Washington, D.C. was a nameless swamp filled with mosquitos. -

85(R) Hr 2021

By:AAWilson H.R.ANo.A2021 RESOLUTION 1 WHEREAS, The observance of American Family Reunion Days from 2 July 1 to 4, 2017, provides an opportunity to celebrate the timeless 3 values on which our nation was founded; and 4 WHEREAS, In 1776, the Second Continental Congress convened in 5 Philadelphia on July 1 to deliberate over a break from tyranny; the 6 following day, the committee of the whole voted in favor of the 7 Resolution for Independence offered by Richard Henry Lee of 8 Virginia; this document declared "that these United Colonies are, 9 and of right ought to be, free and independent States, that they are 10 absolved from all allegiance to the British Crown, and that all 11 political connection between them and the State of Great Britain 12 is, and ought to be, totally dissolved"; and 13 WHEREAS, On July 4, 1776, the Continental Congress adopted 14 the Declaration of Independence, written largely by Thomas 15 Jefferson, with the assistance of John Adams and Ben Franklin; the 16 famous preamble states: "We hold these truths to be self-evident; 17 that all men are created equal; that they are endowed by their 18 Creator with certain inalienable rights; that among these are life, 19 liberty and the pursuit of happiness; that to secure these rights, 20 governments are instituted among men, deriving their just powers 21 from the consent of the governed"; and 22 WHEREAS, Today, citizens continue to treasure the 23 inalienable rights they enjoy as members of the American family, 24 and by marking the anniversary of a tremendous milestone in the 85R27935 BPG-D 1 H.R.ANo.A2021 1 history of democracy and of our nation, we reaffirm our 2 centuries-long commitment to freedom; now, therefore, be it 3 RESOLVED, That the House of Representatives of the 85th Texas 4 Legislature hereby recognize July 1 through 4, 2017, as American 5 Family Reunion Days. -

Declaration of Independence

DECLARATION OF INDEPENDENCE IN CONGRESS, JULY 4, 1776 —————————— THE UNANIMOUS DECLARATION OF THE THIRTEEN UNITED STATES OF AMERICA When, in the course of human events, it becomes necessary for one people to dissolve the political bands which have connected them with another, and to assume among the powers of the earth the separate and equal station to which the laws of nature and nature’s God entitle them, a decent respect to the opinions of mankind requires that they should declare the causes which impel them to the separation. We hold these truths to be self-evident—that all men are created equal; that they are endowed by their Creator with certain unalienable rights; that among these are life, liberty, and the pursuit of happiness; that, to secure these rights, governments are instituted among men, deriving their just powers from the consent of the governed; that whenever any form of government becomes destructive of these ends, it is the right of the people to alter or to abolish it, and to institute new government, laying its foundation on such principles, and organizing its powers in such form, as to them shall seem most likely to effect their safety and happiness. Prudence, indeed, will dictate, that governments long established should not be changed for light and transient causes; and accordingly all experience hath shown, that mankind are more disposed to suffer, while evils are sufferable, than to right themselves by abolishing the forms to which they are accustomed. But when a long train of abuses and usurpations, pursuing invariably the same object, evinces a design to reduce them under absolute despotism, it is their right, it is their duty, to throw off such government and to provide new guards for their future security. -

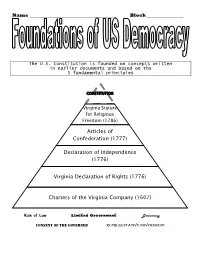

Articles of Confederation (1777) Declaration of Independence (1776

Name ______________________________________ Block ________________ The U.S. Constitution is founded on concepts written in earlier documents and based on the 5 fundamental principles CONSTITUTION Virginia Statute for Religious Freedom (1786) Articles of Confederation (1777) Declaration of Independence (1776) Virginia Declaration of Rights (1776) Charters of the Virginia Company (1607) Rule of Law Limited Government Democracy Consent of the Governed Representative Government Anticipation guide Founding Documents Vocabulary Amend Constitution Independence Repeal Colony Affirm Grievance Ratify Unalienable Rights Confederation Charter Delegate Guarantee Declaration Colonist Reside Territory (land) politically controlled by another country A person living in a settlement/colony Written document granting land and authority to set up colonial governments To make a powerful statement that is official Freedom from the control of others A complaint Freedoms that everyone is born with and cannot be taken away (Life, Liberty, Pursuit of Happiness) To promise To vote to approve To change Representatives/elected officials at a meeting A group of individuals or states who band together for a common purpose To verify that something is true To cancel a law To stay in a place A written plan of government Foundations of American Democracy Across 1. Territory politically controlled by another country 2. To vote to approve 4. Freedom from the control of others 5. Representatives/elected officials at a meeting 8. A complaint 10. To verify that something is true 11. To make a powerful statement that is official 12. To cancel a law 13. To stay in a place 14. A written plan of government Down 1. A group of individuals or states who band together for a common purpose 3. -

Limited Government

03 008-010 Found2 Limit 9/13/07 10:54 AM Page 8 LIMITED GOVERNMENT Thomas Jefferson accurately represented the executing them in a tyrannical manner as well. In his convictions of his fellow colonists when he famous draft of a constitution for the commonwealth observed in the Declaration of Independence that of Massachusetts, Adams declared that the a government, to be considered legitimate, must be “legislative, executive and judicial power shall be based on the consent of the people and respect their placed in separate departments, to the end that it natural rights to “life, liberty and the pursuit of might be a government of laws, and not of men.” happiness.”Along with other leading members of the This document, along with his Defence of the founding generation, Jefferson Constitutions of Government of understood that these principles the United States of America, dictated that the government be containing a strong case for checks given only limited powers that, and balances in government, ideally, are carefully described in were well known to the delegates written charters or constitutions. who attended the Constitutional Modern theorists like John Convention of 1787. Locke and the Baron de James Wilson, one of the Montesquieu had been making foremost legal scholars of the the case for limited government founding period and a delegate and separation of powers during from Pennsylvania at the the century prior to the American Constitutional Convention, agreed Revolution. Colonial Americans with Adams’ insistence that the were quite familiar with Locke’s power of government should be argument from his Two Treatises divided to the end of advancing of Government that “Absolute the peace and happiness of the Arbitrary Power, or Governing without settled people. -

The Constitution and the Other Constitution

William & Mary Bill of Rights Journal Volume 10 (2001-2002) Issue 2 Article 3 February 2002 The Constitution and The Other Constitution Michael Kent Curtis Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarship.law.wm.edu/wmborj Part of the Constitutional Law Commons, and the First Amendment Commons Repository Citation Michael Kent Curtis, The Constitution and The Other Constitution, 10 Wm. & Mary Bill Rts. J. 359 (2002), https://scholarship.law.wm.edu/wmborj/vol10/iss2/3 Copyright c 2002 by the authors. This article is brought to you by the William & Mary Law School Scholarship Repository. https://scholarship.law.wm.edu/wmborj THE CONSTITUTION AND THE OTHER CONSTITUTION Michael Kent Curtis* In this article,Professor Michael Kent Curtisexamines how laws thatshape the distributionof wealth intersect with and affectpopularsovereigntyandfree speech and press. He presents this discussion in the context of the effect of the Other Constitutionon The Constitution. ProfessorCurtis begins by taking a close-up look at the current campaignfinance system and the concentrationof media ownership in a few corporate bodies and argues that both affect the way in which various politicalissues arepresented to the public, ifat all. ProfessorCurtis continues by talking about the origins of our constitutional ideals ofpopular sovereignty and free speech andpressand how the centralizationof economic power has limited the full expression of these most basic of democratic values throughout American history. Next, he analyzes the Supreme Court's decision in Buckley v. Valeo, the controlling precedent with respect to the constitutionality of limitations on campaign contributions. Finally, ProfessorCurtis concludes that the effect of the Other Constitution on The Constitution requires a Television Tea Party and a government role in the financingofpolitical campaigns. -

Interpretations of Mill's Harm Principle and the Economic Implications Therein

Georgia State University ScholarWorks @ Georgia State University Political Science Theses Department of Political Science Fall 11-16-2012 Beyond Libertarianism: Interpretations of Mill's Harm Principle and the Economic Implications Therein Matthew A. Towery Georgia State University Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarworks.gsu.edu/political_science_theses Recommended Citation Towery, Matthew A., "Beyond Libertarianism: Interpretations of Mill's Harm Principle and the Economic Implications Therein." Thesis, Georgia State University, 2012. https://scholarworks.gsu.edu/political_science_theses/45 This Thesis is brought to you for free and open access by the Department of Political Science at ScholarWorks @ Georgia State University. It has been accepted for inclusion in Political Science Theses by an authorized administrator of ScholarWorks @ Georgia State University. For more information, please contact [email protected]. BEYOND LIBERTARIANISM: INTERPRETATIONS OF MILL’S HARM PRINCIPLE AND THE ECONOMIC IMPLICATIONS THEREIN by MATTHEW TOWERY Under the Direction of Mario Feit ABSTRACT The thesis will examine the harm principle, as originally described by John Stuart Mill. In doing so, it will defend that, though unintended, the harm principle may justify several principles of distributive justice. To augment this analysis, the paper will examine several secondary au- thors’ interpretations of the harm principle, including potential critiques of the thesis itself. INDEX WORDS: Mill, Harm principle, Libertarianism, Redistribution,