Identity on the Threshold: the Myth of Persephone in Italian American

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Alumni Revue! This Issue Was Created Since It Was Decided to Publish a New Edition Every Other Year Beginning with SP 2017

AAlluummnnii RReevvuuee Ph.D. Program in Theatre The Graduate Center City University of New York Volume XIII (Updated) SP 2016 Welcome to the updated version of the thirteenth edition of our Alumni Revue! This issue was created since it was decided to publish a new edition every other year beginning with SP 2017. It once again expands our numbers and updates existing entries. Thanks to all of you who returned the forms that provided us with this information; please continue to urge your fellow alums to do the same so that the following editions will be even larger and more complete. For copies of the form, Alumni Information Questionnaire, please contact the editor of this revue, Lynette Gibson, Assistant Program Officer/Academic Program Coordinator, Ph.D. Program in Theatre, The Graduate Center, City University of New York, 365 Fifth Avenue, New York, NY 10016-4309. You may also email her at [email protected]. Thank you again for staying in touch with us. We’re always delighted to hear from you! Jean Graham-Jones Executive Officer Hello Everyone: his is the updated version of the thirteenth edition of Alumni Revue. As always, I would like to thank our alumni for taking the time to send me T their updated information. I am, as always, very grateful to the Administrative Assistants, who are responsible for ensuring the entries are correctly edited. The Cover Page was done once again by James Armstrong, maybe he should be named honorary “cover-in-chief”. The photograph shows the exterior of Shakespeare’s Globe in London, England and was taken in August 2012. -

African-American Women's History and the Metalanguage of Race Author(S): Evelyn Brooks Higginbotham Source: Signs, Vol

African-American Women's History and the Metalanguage of Race Author(s): Evelyn Brooks Higginbotham Source: Signs, Vol. 17, No. 2 (Winter, 1992), pp. 251-274 Published by: The University of Chicago Press Stable URL: http://www.jstor.org/stable/3174464 Accessed: 02/01/2010 19:26 Your use of the JSTOR archive indicates your acceptance of JSTOR's Terms and Conditions of Use, available at http://www.jstor.org/page/info/about/policies/terms.jsp. JSTOR's Terms and Conditions of Use provides, in part, that unless you have obtained prior permission, you may not download an entire issue of a journal or multiple copies of articles, and you may use content in the JSTOR archive only for your personal, non-commercial use. Please contact the publisher regarding any further use of this work. Publisher contact information may be obtained at http://www.jstor.org/action/showPublisher?publisherCode=ucpress. Each copy of any part of a JSTOR transmission must contain the same copyright notice that appears on the screen or printed page of such transmission. JSTOR is a not-for-profit service that helps scholars, researchers, and students discover, use, and build upon a wide range of content in a trusted digital archive. We use information technology and tools to increase productivity and facilitate new forms of scholarship. For more information about JSTOR, please contact [email protected]. The University of Chicago Press is collaborating with JSTOR to digitize, preserve and extend access to Signs. http://www.jstor.org African-AmericanWomen's History and the Metalanguage of Race Evelyn Brooks Higginbotham PT-P HEORETICAL DISCUSSION in African-American wom- en's historybegs for greatervoice. -

Novels of Return

Novels of Return: Ethnic Space in Contemporary Greek-American and Italian-American Literature by Theodora D. Patrona A dissertation submitted to the Department of American Literature and Culture, School of English, Faculty of Philosophy, In fulfilment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy Aristotle University of Thessaloniki, Greece February 2011 i στην οικογένειά μου, Ελισάβετ, Δημήτρη και Λεωνίδα που ενθάρρυνε και υποστήριξε αυτό το «ταξίδι» με όλους τους πιθανούς τρόπους… και στον Μάνο μου, που ήταν πάντα εκεί ξεπερνώντας τις δυσκολίες… ii Acknowledgements This thesis would not have been possible without the inspiration, support and kind help of numerous people. Firstly, my advisor, mentor, and, I dare say, friend, Professor Yiorgos Kalogeras who has always been my most enthusiastic supporter, guiding me with his depths of knowledge in ethnic literature, unfailingly encouraging me to keep going, and consoling me whenever I was disappointed. He has opened his home, his family and circle of scholarly friends, which I appreciate immensely. I would also like to warmly thank the other two members of my committee, Drs. Yiouli Theodosiadou and Nikolaos Kontos for their patience, feedback, thoroughness, and encouraging comments on my work. Moreover, I am indebted to Professor Fred Gardaphé who has welcomed me in the Italian-American literature and scholarship, pointing out new creative paths and outlets. All these years of research, I have been constantly assisted, advised and reassured by my Italian mentor and true friend, Professor Stefano Luconi without whom this dissertation would lack its Italian-American part, and would have probably been left incomplete every time I lost hope. -

The Monumental Olive Trees As Biocultural Heritage of Mediterranean Landscapes: the Case Study of Sicily

sustainability Article The Monumental Olive Trees as Biocultural Heritage of Mediterranean Landscapes: The Case Study of Sicily Rosario Schicchi 1, Claudia Speciale 2,*, Filippo Amato 1, Giuseppe Bazan 3 , Giuseppe Di Noto 1, Pasquale Marino 4 , Pippo Ricciardo 5 and Anna Geraci 3 1 Department of Agricultural, Food and Forest Sciences (SAAF), University of Palermo, 90128 Palermo, Italy; [email protected] (R.S.); fi[email protected] (F.A.); [email protected] (G.D.N.) 2 Departamento de Ciencias Históricas, Facultad de Geografía e Historia, Universidad de Las Palmas de Gran Canaria, 35004 Las Palmas de Gran Canaria, Spain 3 Department of Biological, Chemical and Pharmaceutical Sciences and Technologies (STEBICEF), University of Palermo, 90123 Palermo, Italy; [email protected] (G.B.); [email protected] (A.G.) 4 Bona Furtuna LLC, Los Gatos, CA 95030, USA; [email protected] 5 Regional Department of Agriculture, Sicilian Region, 90145 Palermo, Italy; [email protected] * Correspondence: [email protected] Abstract: Monumental olive trees, with their longevity and their remarkable size, represent an important information source for the comprehension of the territory where they grow and the human societies that have kept them through time. Across the centuries, olive trees are the only cultivated plants that tell the story of Mediterranean landscapes. The same as stone monuments, these green monuments represent a real Mediterranean natural and cultural heritage. The aim of this paper is to discuss the value of monumental trees as “biocultural heritage” elements and the role they play in Citation: Schicchi, R.; Speciale, C.; the interpretation of the historical stratification of the landscape. -

Recognizing Female Desire and Subjectivity in the Oedipus Complex

Jenna Davis 1 Beyond Castration: Recognizing Female Desire and Subjectivity in the Oedipus Complex Je=aDavis Critical Theory Swathmore College December 2011 Jenna Davis 2 CHAPTER 1 Argument and Methodology Psychoanalysis was developed by Austrian physician Sigmund Freud in the late nineteenth and early twentieth centuries. One of Freud's most celebrated theories was that of the Oedipus complex, which explores the psychic structures that underlie sexual development. In the following chapters I will be examining the Oedipal and preoedipal stages of psychosexual development, drawing out their implicit gendered assumptions with the help of modern feminist theorists and psychoanalysts. I am pursuing a Lacanian reading of Freud, in which the biological roles of mother and father are given structural importance, so that whomever actually occupies these roles is less important than their positional significance. After giving a brief history of the evolution of psychoanalytic theory in the first chapter, I move on in the second chapter to explicate Freud's conception of the Oedipus complex (including the preoedipal stage) and the role of the Oedipal myth, making use of theorist Teresa de Lauretis. In the third chapter, I look at several of Freud's texts on femininity and female sexuality. I will employ Simone de Beauvoir, Kaja Silverman and de Lauretis to discuss male and female investments in femininity and the identities that are open to women. After this, Jessica Benjamin takes the focus away from individuals and incorporates the other in her theory of intersubjectivity. I end chapter three with Helene Cixous, Julia Kristeva and Luce Irigaray, who all attest to the necessity of symbolic female representation--Cixous proposes a specifically female manner of writing called ecriture feminine, Kristeva introduces the semiotic realm to contend with Lacan's symbolic realm, and Irigaray believes in the need for corporeal Jenna Davis 3 representation for women within a female economy. -

Raquel Z. Rivera Puerto Rican Artist & Scholar

Fall–Winter 2013 Volume 39: 3–4 The Journal of New York Folklore Raquel Z. Rivera Puerto Rican Artist & Scholar Remembering Pete Seeger Irish Lace in Western NY Fair Fotos A Portrait of Karyl Denison Eaglefeathers (1952–2012) From the Director From the Editor On September 17, Henry’s nomination was supported by several What a blow to hear of 2014, Henry Arquette folklorists and folklore organizations, and it Peter Seeger’s death on received the highest was promoted by members of his Mohawk January 27, 2014 at the award that this na- community, in recognition of his importance age of 94. tion offers to folk and not only as a traditional artist but also for his I thought the man traditional artists. A prominence in teaching others to carry on would live forever. maker of utilitarian the tradition. One can’t say with certainty What a champion of so baskets held in high what the effect of this award will have for the many causes over the regard by his Haude- future. The youngest members in attendance, decades of his life, and nosaunee Mohawk community, Henry Ar- great grandchildren of Henry Arquette, made a master of weaving music into this activism. quette was one of nine award honorees for the nine-hour journey from Akwesasne to I’m so glad to have joined recent 2014, and the only artist from New York State Washington, DC, to witness the ceremony. celebrations of his life’s work. At last year’s to receive the National Endowment for the Their wide-eyed look at the ceremony and benefit concert at Proctors Theater in Arts National Heritage Fellowship Award for its trappings of splendor will without doubt Schenectady, I enthusiastically sang along 2014. -

Studies in Early Mediterranean Poetics and Cosmology

The Ruins of Paradise: Studies in Early Mediterranean Poetics and Cosmology by Matthew M. Newman A dissertation submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy (Classical Studies) in the University of Michigan 2015 Doctoral Committee: Professor Richard Janko, Chair Professor Sara L. Ahbel-Rappe Professor Gary M. Beckman Associate Professor Benjamin W. Fortson Professor Ruth S. Scodel Bind us in time, O Seasons clear, and awe. O minstrel galleons of Carib fire, Bequeath us to no earthly shore until Is answered in the vortex of our grave The seal’s wide spindrift gaze toward paradise. (from Hart Crane’s Voyages, II) For Mom and Dad ii Acknowledgments I fear that what follows this preface will appear quite like one of the disorderly monsters it investigates. But should you find anything in this work compelling on account of its being lucid, know that I am not responsible. Not long ago, you see, I was brought up on charges of obscurantisme, although the only “terroristic” aspects of it were self- directed—“Vous avez mal compris; vous êtes idiot.”1 But I’ve been rehabilitated, or perhaps, like Aphrodite in Iliad 5 (if you buy my reading), habilitated for the first time, to the joys of clearer prose. My committee is responsible for this, especially my chair Richard Janko and he who first intervened, Benjamin Fortson. I thank them. If something in here should appear refined, again this is likely owing to the good taste of my committee. And if something should appear peculiarly sensitive, empathic even, then it was the humanity of my committee that enabled, or at least amplified, this, too. -

MYTHOLOGY – ALL LEVELS Ohio Junior Classical League – 2012 1

MYTHOLOGY – ALL LEVELS Ohio Junior Classical League – 2012 1. This son of Zeus was the builder of the palaces on Mt. Olympus and the maker of Achilles’ armor. a. Apollo b. Dionysus c. Hephaestus d. Hermes 2. She was the first wife of Heracles; unfortunately, she was killed by Heracles in a fit of madness. a. Aethra b. Evadne c. Megara d. Penelope 3. He grew up as a fisherman and won fame for himself by slaying Medusa. a. Amphitryon b. Electryon c. Heracles d. Perseus 4. This girl was transformed into a sunflower after she was rejected by the Sun god. a. Arachne b. Clytie c. Leucothoe d. Myrrha 5. According to Hesiod, he was NOT a son of Cronus and Rhea. a. Brontes b. Hades c. Poseidon d. Zeus 6. He chose to die young but with great glory as opposed to dying in old age with no glory. a. Achilles b. Heracles c. Jason d. Perseus 7. This queen of the gods is often depicted as a jealous wife. a. Demeter b. Hera c. Hestia d. Thetis 8. This ruler of the Underworld had the least extra-marital affairs among the three brothers. a. Aeacus b. Hades c. Minos d. Rhadamanthys 9. He imprisoned his daughter because a prophesy said that her son would become his killer. a. Acrisius b. Heracles c. Perseus d. Theseus 10. He fled burning Troy on the shoulder of his son. a. Anchises b. Dardanus c. Laomedon d. Priam 11. He poked his eyes out after learning that he had married his own mother. -

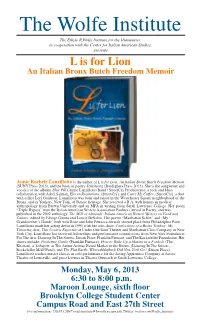

The Wolfe Institute

The Wolfe Institute The Ethyle R.Wolfe Institute for the Humanities, in cooperation with the Center for Italian American Studies, presents L is for Lion An Italian Bronx Butch Freedom Memoir Annie Rachele Lanzillotto is the author of L is for Lion: An Italian Bronx Butch Freedom Memoir (SUNY Press 2013), and the book of poetry Schistsong (Bordighera Press 2013). She is the songwriter and vocalist of the albums Blue Pill (Annie Lanzillotto Band / StreetCry Productions), a rock and blues collaboration with Adeel Salman, Eleven Recitations, (StreetCry), and Carry My Coffee, (StreetCry), a duet with cellist Lori Goldston. Lanzillotto was born and raised in the Westchester Square neighborhood of the Bronx, and in Yonkers, New York, of Barese heritage. She received a B.A. with honors in medical anthropology from Brown University and an MFA in writing from Sarah Lawrence College. Her poem “Triple Bypass” won the Italian American Writers Association Paolucci Award in Poetry, and was published in the 2002 anthology, The Milk of Almonds: Italian-American Women Writers on Food and Culture, edited by Edvige Giunta and Louise DeSalvo. Her poems “Manhattan Schist” and “My Grandmother’s Hands” both won Rose and John Petracca Awards second place from Philadelphia Poets. Lanzillotto made her acting debut in 1993 with her solo show, Confessions of a Bronx Tomboy: My Throwing Arm, This Useless Expertise at Under One Roof Theater and Manhattan Class Company in New York City. Lanzillotto has received fellowships and performance commissions from New York Foundation For The Arts, Dancing In The Streets, Dixon Place, Franklin Furnace, and The Rockefeller Foundation. -

Carried Away: 'Revisioning' Feminist Film Theory Toward a Radical Practice

MA MAJOR RESEARCH PAPER Carried away: 'revisioning' feminist film theory toward a radical practice Submitted by Kimberley Radmacher - Supervisor: Professor Scott Forsyth The Major Research Paper is submitted in partial fulfillment ofthe requirements for the degree of Master of Arts Joint Graduate Programme in Communication & Culture Ryerson University - York University Toronto, Ontario, Canada April 30, 2004 Carried away: 'revisioning' feminist film theory toward a radical practice The question of women's expression has been one of both self-expression and communication with other women, a question at once of the creation/invention of new images and of the creation/imaging of new forms of community. Ifwe rethink the problem of a specificity of women's cinema and aesthetic forms in this manner, in terms of address- who is making films for whom, who is looking and speaking, how, where, and to whom--then what has been seen as a rift, a division, an ideological split within feminist film culture between theory and practice, or between formalism and activism, may appear to be the very strength, the drive and productive heterogeneity of feminism. 1 It's difficult to believe that after over 30 years of feminist theory "breaking the glass ceiling" is still a term often heard from women professionals. Still, while women continue to make up a trifling percentage of CEOs in Fortune 500 companies, and are continually paid 72% of the wages of their male counterparts,2 small advances continue to be made by women in both these areas? Yet, one profession that stands out as persistently keeping women on the outside looking in is mainstream filmmaking, especially directing. -

Queer Texts, Bad Habits, and the Issue of a Future Teresa De Lauretis

Queer Texts, Bad Habits, and the Issue of a Future Teresa de Lauretis GLQ: A Journal of Lesbian and Gay Studies, Volume 17, Numbers 2-3, 2011, pp. 243-263 (Article) Published by Duke University Press For additional information about this article https://muse.jhu.edu/article/437427 Access provided by University of Arkansas @ Fayetteville (29 Dec 2016 08:37 GMT) QUEER TEXTS, BAD HABITS, AND THE ISSUE OF A FUTURE Teresa de Lauretis Heterotopias are disturbing, probably because they secretly under- mine language, because they make it impossible to name this and that, because they shatter or tangle common names, because they destroy “syntax” in advance, and not only the syntax with which we construct sentences but also that less apparent syntax which causes words and things (next to and also opposite one another) to “hold together.” — Michel Foucault, The Order of Things My reflections on some themes of this special issue on queer bonds, sexuality and sociability, negativity and futurity, are indebted to the research and thinking involved in my recent book about the figuration of sexuality as drive in Freud and in literary and film texts.1 One of those texts, Djuna Barnes’s Nightwood (1936), has received much attention in feminist criticism and in the history of literary modernism but has been strangely disregarded in queer studies. My own psycho- analytic-literary reading of the novel did not specifically address its place in a possible archive of queer literary writing, a project that also exceeds the scope of this essay.2 Were I to undertake -

Preface Introduction

Notes Preface 1. Luisa Pretolani's video, Things I Take, which deals with Indian women im migrants, speaks to the experience of emigration in ways that transcend the specific experience of a single ethnic group. The issues the women who appear in this video address relate to the significance of and repercussions on one's sense of self of the separation from one's homeland. 2. See Gilbert and Gubar's feminist classic The Madwoman in the Attic (1979), in which they ofTer adefinition of anxiety of authorship, which they jux tapose to the more masculine "anxiety of influence" (50), the title subject of Harold Bloom's study. 3. I began to study Italian American literature and minority literatures not in graduate school, but in the years following my graduation, in the early 1990s. 4. My first actual encounter with Italian American literature actually oc curred in 1983, at a conference on Italian American Studies of the AISNA (ItalianAssociation ofNorthAmerican Studies).The conference was orga nized by my then professor of American Literature at the University of Catania, Maria Vittoria D'Amico. I was one of a handful of undergraduate students involved in the organization of the conference. There, I met sev eral American professors, includingJohn Paul Russo, who would later ofTer me a teaching assistantship at the University of Miami. 5. Giunta, "The Quest forTrue Love: Nancy Savoca's Domestic Film Comedy." 6. In 1987, DeSalvo had also published-in England-Casting Off, an outra geous novel about Italian American women and adultery. 7. Oddly enough, much like other women and minority writers who, once they started looking, found literary sisters and ancestors, I, too, would later discover two other writers in my family, Giuseppe Minasola and Laura Emanuelita Minasola.