Utah's Grand Staircase: the Right Path to Wilderness Preservation?

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Program | Abstracts | Lecturers

11 March 2021 International conference ‘NATIONAL FORGETTING AND MEMORY: THE DESTRUCTION OF "NATIONAL" MONUMENTS FROM A COMPARATIVE PERSPECTIVE’ Program | Abstracts | Lecturers Organised by NISE and the Museum at the Yser In cooperation with: INDEX OF LECTURES KEY NOTE 1. Monumentality and Its Discontents: How the Past is Unforgotten. A. Rigney SESSION 1. Nation vs Regional vs Local Memories Chaired by Bruno De Wever City Monuments in Contemporary Kharkiv: Construction of the National and Regional Memory. V. Sukovata Nationalising Scorched Earth – Memory and destruction of monuments from Vukovar to Knin. M. Piasek Fascist monuments and their divided memories in Trieste and Bolzano. I. Pupella-Noguès SESSION 2. Nation-state, ideology and monuments Chaired by Chantal Kesteloot Reactions and counter reactions: The removal of Hoxha’s monuments and Albania’s tortuous transition. K. Këlliçi Present absence or absent presence. Monuments dedicated to the Yugoslav partisan struggle between future present and present perfect. L. Lovrenčić. and T. Pupovac «War on monuments» in Poland and its implications for the national historical policy. M. Pavlova KEY NOTE 2. Animated Stones: drawing a picture of the “IJzertoren’s” destruction via the lens of editorial cartoons. K. Swerts SESSION 3. Global and contemporary perspectives Chaired by K. Swerts A Knee on the Neck: Problematic Commemorative Practices in the United States. K. Shelby Set in Stone? Monuments, National Identity & John A. Macdonald. C. Spicer A Fractured Door: The Contested History of the IRS. J. Dawson Portraying and preserving the South African past – a monumental challenge. A. Bailey SESSION 4. The politics of resurrection Chaired by Marnix Beyen Staged reconstruction: On the scenography of the IJzertoren’s building site. -

The Lightning Bolt Page 2

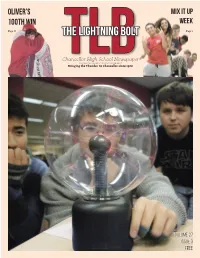

Oliver’s Mix It Up 100th win Week Page 17 The Lightning Bolt Page 2 Chancellor High School Newspaper TLB6300 Harrison Road, Fredericksburg, VA 22407 Bringing the Thunder to Chancellor since 1988 Volume 27 Issue 3 FREE 1 November 2014 what IS HAPPENING? Photo by Neil Schubel Neil Photo by Kids flocked to Mix It Up tables during lunch to take their pledge. Mix It Up week challenges kids to identify, cross and challenge social boundaries. Many students took thier pledge to mix it up in the week of November 10th till the 14th. Photo by Yearbook Staff Yearbook Photo by Photo by Neil Schubel Neil Photo by Schubel Neil Photo by Schubel Neil Photo by Tyler Jacobs models his painted Kenneth Ryan was spotted in the Jamie Smith in the process of a Joshua Edney jumps in the air in cheek in Mix It Up Week. halls with a fake skull. painted heart in Mix It Up Week. excitement. Photo courtesy of April Kniebbe April of Photo courtesy Nostalgia November! Who remembers the ALS Ice Bucket Challenge? The football coaches certainly do as they accepted the ALS Ice Bucket Challenge this July. A few players dumped the buckets as the team stood around to watch their coaches get ice buckets dumped on their heads. November 2014 2 Contents Editorial By Neil Schubel coming of winter if you look to by Chancellor’s Sociology Class Mrs. Gattie Editor-in-Chief some cases in states like New was also a huge success as near- Adviser It will ruin the happiest of York that are getting up to four ly 800 students took the pledge mornings waking up and realiz- feet of snow). -

2013 Winter Athletic Awards Ceremony Wednesday, Ma

The Loomis Chaffee School 2012-2013 Winter Athletic Awards Ceremony Wednesday, March 27, 2013 Alpine Skiing Boys Basketball Girls Basketball Boys Hockey Girls Hockey Boys Swimming Girls Swimming Boys Squash Girls Squash Wrestling Loomis Chaffee Winter Athletic Awards Ceremony Wednesday, March 27, 2013 6:30 p.m. Loomis Dining Hall Tonight’s Program Welcome Remarks: Bob Howe ’80, Athletic Director Alpine Skiing: Jake Leyden Girls Squash: Naomi Appel Boys Squash: Elliot Beck Girls Swimming: Bob DeConinck Boys Swimming: Fred Seebeck Girls Hockey Liz Leyden Boys Hockey John Zavisza Boys Basketball Jim Dargati ‘85 Girls Basketball Adrian Stewart ‘90 Wrestling Ben Haldeman 2012-2013 Winter Athletic Award Winners Alpine Skiing All New England: Tucker Santoro, Sara Corsetti Most Valuable Skiier: Tucker Santoro Coaches’ Award: Theodora Cohen Boys Varsity Basketball All New England: Joe Stortini Coaches’ Award: Durelle Napier Coaches’ Award: Dale Reese Most Valuable Player: Joe Stortini Girls Varsity Basketball All New England: Steph Jones and Abby Pyne Most Valuable Player: Steph Jones Most Improved: Chynna Bailey Coaches’ Award: Brooke Marchitto Boys Varsity Hockey U.S.HR Prep School Player of the Year Danny Tirone All New England Team: Danny Tirone Most Valuable Player: Danny Tirone Coaches’ Award: EJ Culhane Coaches’ Award: Nick Miceli Golden Buoy: Stephen Picard Girls Varsity Hockey Coaches’ Award: Brittany Bugalski Coaches’ Award: Molly Strabley Boys Varsity Squash Most Valuable Player: Alex Steel Most Improved Player: Kevin Cha Coaches’ Award: -

Little Boy, the Antichristchild. the Beast in the Nuclear

UTTLE BOY, THE ANTICHRISTCHILD: THE BEAST IN THE NUCLEAR AGE EDDIE TAFO YA University of New México, USA (Resumen) El presente trabajo intenta demostrar cómo el "anticristo" de John Divine está hoy presente en la bomba atómica. La bomba no sólo ha atraido la atención de h'deres y empresas mundiales quienes la cuestionan y se preguntan "¿Quién puede luchar contra ella?" sino que además ejerce un control totalitario sobre el planeta. Al igual que el "corazón" de John, la bomba en un principio devolvió la paz a un mundo caótico, hizo iimumerables promesas y dijo numerosas blasfemias antes de asumir el papel del dios de la era moderna. The Wonum, the Beast and the Voice in the WUdaness In 1964, Robert Mosely stalked, stabbed, raped, and murdered Kitty Genovese on a New York City Street while 38 people listened to her cries and did nothing. Some even puUed chairs up to their windows to watch the horror.' While this is a sad commentary on U.S. culture, it is a paradigm theological moment. It is the Parable of the Good Samaritan transplanted from Luke's Gospel into modern times. On a theological level, the cries were not merely those of Kitty Genovese but the cries of the eternal Other, the person in need. While Christianity smce the time of Constantino has been a tool for the oppressing of gays, women, non-capitalists, and others, there is a persisten! line of thought which advócales that Jesús' message was not as much a matter of orthodoxy as it is a matter of orthopraxies; it is not so much a religión of repentance as it is a religión of divine duty predicated on listening and responding to the voice of the Other. -

ROMA SURRECTA: Portrait of a Counterinsurgent Power, 216 BC - AD 72

University of Pennsylvania ScholarlyCommons CUREJ - College Undergraduate Research Electronic Journal College of Arts and Sciences 5-2011 ROMA SURRECTA: Portrait of a Counterinsurgent Power, 216 BC - AD 72 Emerson T. Brooking University of Pennsylvania, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: https://repository.upenn.edu/curej Part of the Ancient History, Greek and Roman through Late Antiquity Commons, Comparative Politics Commons, Military History Commons, and the Other Political Science Commons Recommended Citation Brooking, Emerson T., "ROMA SURRECTA: Portrait of a Counterinsurgent Power, 216 BC - AD 72" 01 May 2011. CUREJ: College Undergraduate Research Electronic Journal, University of Pennsylvania, https://repository.upenn.edu/curej/145. This paper is posted at ScholarlyCommons. https://repository.upenn.edu/curej/145 For more information, please contact [email protected]. ROMA SURRECTA: Portrait of a Counterinsurgent Power, 216 BC - AD 72 Abstract This study evaluates the military history and practice of the Roman Empire in the context of contemporary counterinsurgency theory. It purports that the majority of Rome’s security challenges fulfill the criteria of insurgency, and that Rome’s responses demonstrate counterinsurgency proficiency. These assertions are proven by means of an extensive investigation of the grand strategic, military, and cultural aspects of the Roman state. Fourteen instances of likely insurgency are identified and examined, permitting the application of broad theoretical precepts -

A Case Study of Revolutionary War and War of the Regulation Battlefields in North and South Carolina

Leon Dure. Interconnectedness: A Case Study of Revolutionary War and War of the Regulation Battlefields in North and South Carolina. A Master’s Paper for the M.S. in LS degree. May 2020. 120 pages. Advisor: Megan Winget This paper examines the preservation and interpretation practices of six battlefields in North and South Carolina, all of which occurred during the American Revolution or the War of the Regulation. I not only conducted interviews with personnel at the sites in question, but also examined resources related to each site, as well as the National Park Service in general. I discovered that in multiple locations preservation and interpretation are interconnected, in that each has a broad, rather than narrow focus. Specifically, both concentrate not just on the battlefield itself and what occurred on a specific day, but also contextual information that helps enlighten visitors to the importance of the site. Headings: Battlefield Interpretation Preservation 3D Technology 2 INTERCONNECTEDNESS: A CASE STUDY OF REVOLUTIONARY WAR AND WAR OF THE REGULATION BATTLEFIELDS IN NORTH AND SOUTH CAROLINA AND HOW IT APPLIES TO LIBRARY AND INFORMATION SCIENCE by Leon S. Dure A Master’s paper submitted to the faculty of the School of Information and Library Science of the University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Master of Science in Library Science. Chapel Hill, North Carolina May 2020 Approved by _______________________________________ Megan Winget 1 1. Introduction ………………………………………………………………………….3 2. Literature Review........................................................................................................ 7 2.1 Preservation Theory ............................................................................................ 7 2.2 Types of Preservation (Digital, 3D, etc.) ............................................................ 9 2.3 Battlefields, Memorials, and Museums (General) ........................................... -

Agrarian Capitalism's Genocidal Trail

Agrarian Capitalism’s Genocidal Trail: The Saga of the Guarani-Kaiowa Antonio A. R. Ioris Cardiff University, School of Geography and Planning, Glamorgan Building, King Edward VII Avenue, Cardiff, Wales, CF10 3WA, United Kingdom [email protected]; Phone: 0044 (0)29 20874845; Fax: 0044 (0)29 2087 4022 ORCID: http://orcid.org/0000-0003-0156-2737 Abstract: Although genocide is an expression commonly used today in relation to the dramatic challenges faces by indigenous peoples around the world, the significance of the Guarani-Kaiowa genocidal experience is not casual and cannot be merely sloganised. The indigenous genocide unfolding in the Brazilian State of Mato Grosso do Sul – Kaiowcide – is not just a case of hyperbolic violence or widespread murdering, but it is something qualitatively different from other serious crimes committed against marginalised, subaltern communities. Kaiowcide is actually the reincarnation of old genocidal practices of agrarian capitalism employed to extend and unify the national territory. In other words, Kaiowcide has become a necessity of mainstream development, whilst the sanctity of regional economic growth and private rural property are excuses invoked to justify the genocidal trail. The phenomenon combines strategies and procedures based on the competition and opposition between groups of people who dispute the same land and the relatively scarce social opportunities of an agribusiness-based economy. Only the focus in recent years may have shifted from assimilation and confinement to abandonment and confrontation, but the intent to destabilise and eliminate the original inhabitants of the land through the asphyxiation of their religion, identity and, ultimately, geography seems to rage unabated. -

TAL Direct: Sub-Index S912c Index for ASIC

TAL.500.002.0503 TAL Direct: Sub-Index s912C Index for ASIC Appendix B: Reference to xv: A list of television programs during which TAL’s InsuranceLine Funeral Plan advertisements were aired. 1 90802531/v1 TAL.500.002.0504 TAL Direct: Sub-Index s912C Index for ASIC Section 1_xv List of TV programs FIFA Futbol Mundial 21 Jump Street 7Mate Movie: Charge Of The #NOWPLAYINGV 24 Hour Party Paramedics Light Brigade (M-v) $#*! My Dad Says 24 HOURS AFTER: ASTEROID 7Mate Movie: Duel At Diablo (PG-v a) 10 BIGGEST TRACKS RIGHT NOW IMPACT 7Mate Movie: Red Dawn (M-v l) 10 CELEBRITY REHABS EXPOSED 24 hours of le mans 7Mate Movie: The Mechanic (M- 10 HOTTEST TRACKS RIGHT NOW 24 Hours To Kill v a l) 10 Things You Need to Know 25 Most Memorable Swimsuit Mom 7Mate Movie: Touching The Void 10 Ways To Improve The Value O 25 Most Sensational Holly Melt -CC- (M-l) 10 Years Younger 28 Days in Rehab 7Mate Movie: Two For The 10 Years Younger In 10 Days Money -CC- (M-l s) 30 Minute Menu 10 Years Younger UK 7Mate Movie: Von Richthofen 30 Most Outrageous Feuds 10.5 Apocalypse And Brown (PG-v l) 3000 Miles To Graceland 100 Greatest Discoveries 7th Heaven 30M Series/Special 1000 WAYS TO DIE 7Two Afternoon Movie: 3rd Rock from the Sun 1066 WHEN THREE TRIBES WENT 7Two Afternoon Movie: Living F 3S at 3 TO 7Two Afternoon Movie: 4 FOR TEXAS 1066: The Year that Changed th Submarin 112 Emergency 4 INGREDIENTS 7TWO Classic Movie 12 Disney Tv Movies 40 Smokin On Set Hookups 7Two Late Arvo Movie: Columbo: 1421 THE YEAR CHINA 48 Hour Film Project Swan Song (PG) DISCOVERED 48 -

The Complete Idiot''s Guide to European History

European History by Nathan Barber A member of Penguin Group (USA) Inc. European History by Nathan Barber A member of Penguin Group (USA) Inc. For Christy, Noah, and Emma ALPHA BOOKS Published by the Penguin Group Penguin Group (USA) Inc., 375 Hudson Street, New York, New York 10014, U.S.A. Penguin Group (Canada), 10 Alcorn Avenue, Toronto, Ontario, Canada M4V 3B2 (a division of Pearson Penguin Canada Inc.) Penguin Books Ltd, 80 Strand, London WC2R 0RL, England Penguin Ireland, 25 St Stephen’s Green, Dublin 2, Ireland (a division of Penguin Books Ltd) Penguin Group (Australia), 250 Camberwell Road, Camberwell, Victoria 3124, Australia (a division of Pearson Australia Group Pty Ltd) Penguin Books India Pvt Ltd, 11 Community Centre, Panchsheel Park, New Delhi—110 017, India Penguin Group (NZ), cnr Airborne and Rosedale Roads, Albany, Auckland 1310, New Zealand (a division of Pearson New Zealand Ltd) Penguin Books (South Africa) (Pty) Ltd, 24 Sturdee Avenue, Rosebank, Johannesburg 2196, South Africa Penguin Books Ltd, Registered Offices: 80 Strand, London WC2R 0RL, England Copyright © 2006 by Nathan Barber All rights reserved. No part of this book shall be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted by any means, electronic, mechanical, photocopying, recording, or otherwise, without written permission from the publisher. No patent liability is assumed with respect to the use of the information contained herein. Although every precaution has been taken in the preparation of this book, the publisher and author assume no responsibility for errors or omissions. Neither is any liability assumed for damages resulting from the use of information contained herein. -

The Association for Diplomatic Studies and Training Foreign Affairs Oral History Project

The Association for Diplomatic Studies and Training Foreign Affairs Oral History Project AMBASSADOR THOMAS J. MILLER Interviewed by: Charles Stuart Kennedy Initial interview date: April 19, 2010 Copyright 2011 ADST TABLE OF CONTENTS Background Born in Illinois, raised in Illinois and Louisiana University of Michigan Field Studies in Thailand and Laos Army Volunteer Research study Joined the Foreign Service in 1976 State Department: Bureau of Intelligence and Research (INR) 1976-1977 South East Asia analyst Operations National Intelligence Estimates (NIE) Philip Habib State Department: Special Assistant to the Undersecretary of State for 1977-1979 Political Affairs Operations Philip Habib Richard Holbrooke American Foreign Service Association (AFSA) David Newsom Indochinese refugees Geneva refugee Conference Soviet troops in Cuba Chiang Mai, Thailand; Vice Consul 1979-1981 Family Temporary assignments Refugee camps Non-Government Organizations (NGOs) Laos government Narcotics Joyce Powers murder Domino Theory 1 State Department: Political/Military Officer: Israeli-Palestine Affairs 1981-1983 Lebanon War Office personnel Israelis bomb Osirak facility American Jewish lobby Israelis invade Lebanon Sabra and Shatila PLO State Department: Bureau of Congressional Affairs; Middle East 1983-1984 Marine barracks bombed (Temporary Duty) Chief of Staff to Special Envoy to Middle East, Donald Rumsfeld Staff members Lebanese government Syria Ambassador Reggie Bartholomew Iran-Iraq War Barak Commission Begin resignation US Lebanon policy Soviets The -

Mestizo) Identity and Other Mestizo Voices Ellis Hurd University of Northern Iowa

University of Northern Iowa UNI ScholarWorks Electronic Theses and Dissertations Graduate College 2008 The eflexr ivity of pain and privilege: An autoethnography of (Mestizo) identity and other Mestizo voices Ellis Hurd University of Northern Iowa Copyright ©2008 Ellis Hurd Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarworks.uni.edu/etd Part of the Bilingual, Multilingual, and Multicultural Education Commons Let us know how access to this document benefits oy u Recommended Citation Hurd, Ellis, "The eflexr ivity of pain and privilege: An autoethnography of (Mestizo) identity and other Mestizo voices" (2008). Electronic Theses and Dissertations. 739. https://scholarworks.uni.edu/etd/739 This Open Access Dissertation is brought to you for free and open access by the Graduate College at UNI ScholarWorks. It has been accepted for inclusion in Electronic Theses and Dissertations by an authorized administrator of UNI ScholarWorks. For more information, please contact [email protected]. THE REFLEXIVITY OF PAIN AND PRIVILEGE: AN AUTOETHNOGRAPHY OF (MESTIZO) IDENTITY AND OTHER MESTIZO VOICES A Dissertation Submitted in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree Doctor of Education Approved: Dr. John K. Smith, Chair Dr. Kurt S. Meredith, Committee Member Dr. Lynn E. Nielsen, Committee Member Dr. Deborah L. Tidwell, Committee Member Dr. Tammy S. Gregersen, Committee Member Ellis Hurd University of Northern Iowa December 2008 UMI Number: 3343925 Copyright 2008 by Hurd, Ellis All rights reserved. INFORMATION TO USERS The quality of this reproduction is dependent upon the quality of the copy submitted. Broken or indistinct print, colored or poor quality illustrations and photographs, print bleed-through, substandard margins, and improper alignment can adversely affect reproduction. -

Magazine Fall 2017 Volume 3, Issue 2

A BI-ANNUAL PUBLICATION OF ALLIED LAND COMMAND MAGAZINE FALL 2017 VOLUME 3, ISSUE 2 06-07 10-13 21 24-25 30-31 LANDCOM: GE/NL CORPS: MNC-NE: NRDC-ESP: RRC-FRA: Road to Trident Javelin Ready for Operations: Road Certified as a high- Communications during Joint Task Force to a land-centric JTF HQ readiness HQ the eNRF/VJTF Certification CONTENTS The LANDPOWER magazine is a bi-an- nual publication produced by Allied Land 4 Command Messages Command (LANDCOM) dedicated to the promotion of actions and ideas, contrib- uting to the improvement of the NATO 6 Road to Trident Javelin Force Structure (NFS) efficiency and effectiveness. The views expressed in this 8 Exercise Dacian Guardian publication do not necessarily reflect those of the LANDCOM Commander, SACEUR, NATO or its member nations and cannot 9 eFP Site Visits be quoted as an official statement of those entities. An electronic version that includes 10 Ready for Operations additional links to in-depth articles, supplementary articles and an ability to provide online comments is available from 14 Thoughts on Land Warfare the LANDCOM website (www.lc.nato.int). 17 Chiefs of Staff Conference 18 Changing Concepts of War To contact the LANDPOWER Magazine staff and/or to submit an article to be con- sidered for publication in the next issue, 21 MNC-NE Certification please use the following contacts: 22 Cooperative Security E-mail: [email protected] Postal: Public Affairs Office 24 Communications during eNRF/VJTF General Vecihi Akin Garrison 35148 Izmir / Turkey 26 From the Frontline: Wheels in Motion All articles are edited for length and con- tent.