The Association for Diplomatic Studies and Training Foreign Affairs Oral History Project

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Program | Abstracts | Lecturers

11 March 2021 International conference ‘NATIONAL FORGETTING AND MEMORY: THE DESTRUCTION OF "NATIONAL" MONUMENTS FROM A COMPARATIVE PERSPECTIVE’ Program | Abstracts | Lecturers Organised by NISE and the Museum at the Yser In cooperation with: INDEX OF LECTURES KEY NOTE 1. Monumentality and Its Discontents: How the Past is Unforgotten. A. Rigney SESSION 1. Nation vs Regional vs Local Memories Chaired by Bruno De Wever City Monuments in Contemporary Kharkiv: Construction of the National and Regional Memory. V. Sukovata Nationalising Scorched Earth – Memory and destruction of monuments from Vukovar to Knin. M. Piasek Fascist monuments and their divided memories in Trieste and Bolzano. I. Pupella-Noguès SESSION 2. Nation-state, ideology and monuments Chaired by Chantal Kesteloot Reactions and counter reactions: The removal of Hoxha’s monuments and Albania’s tortuous transition. K. Këlliçi Present absence or absent presence. Monuments dedicated to the Yugoslav partisan struggle between future present and present perfect. L. Lovrenčić. and T. Pupovac «War on monuments» in Poland and its implications for the national historical policy. M. Pavlova KEY NOTE 2. Animated Stones: drawing a picture of the “IJzertoren’s” destruction via the lens of editorial cartoons. K. Swerts SESSION 3. Global and contemporary perspectives Chaired by K. Swerts A Knee on the Neck: Problematic Commemorative Practices in the United States. K. Shelby Set in Stone? Monuments, National Identity & John A. Macdonald. C. Spicer A Fractured Door: The Contested History of the IRS. J. Dawson Portraying and preserving the South African past – a monumental challenge. A. Bailey SESSION 4. The politics of resurrection Chaired by Marnix Beyen Staged reconstruction: On the scenography of the IJzertoren’s building site. -

Extensions of Remarks E1455 EXTENSIONS of REMARKS

July 27, 2001 CONGRESSIONAL RECORD — Extensions of Remarks E1455 EXTENSIONS OF REMARKS MEMORIAL DAY PRAYER, MYRTLE Let him live, let him live, Bring him home! engagement in Belarus and Chechnya, for ex- HILL CEMETERY GIVEN BY REV. (Les Miserables) ample, illustrates the constructive possibilities WARREN JONES Four score and seven years have passed of the chairmanship. I appreciate Foreign Min- since Romans gathered on this very hill to ister Geoana’s willingness to speak out on bury our President’s wife—Roman Ellen Lou- human rights concerns throughout the region. HON. BOB BARR ise Axson. For the next four score and seven years, As Chair-in-Office, we also hope that Roma- OF GEORGIA nia will lead by example as it continues to im- IN THE HOUSE OF REPRESENTATIVES and all the years to follow, keep us ever mindful this is one nation under God. plement economic and political reform and to Friday, July 27, 2001 Amen. further its integration into western institutions. In this regard, I would like to draw attention to Mr. BARR of Georgia. Mr. Speaker, Rev. f Warren Jones of Rome, Georgia, has long a few of the areas the Helsinki Commission is been an active member of the community. A PROCLAMATION RECOGNIZING following with special interest. First, many members of the Helsinki Com- From his participation during college in every THE OUTSTANDING WORK OF mission have repeatedly voiced our concerns organization on campus except the Women’s THE CITY OF HEATH, OHIO FIRE DEPARTMENT about manifestations of anti-Semitism in Ro- and the Home Economics Clubs, to the 18 mania, often expressed through efforts to re- agencies with which he currently volunteers, in habilitate or commemorate Romania’s World addition to being a member of the Silver HON. -

SPARKS ACROSS the GAP: ESSAYS by Megan E. Mericle, B.A

SPARKS ACROSS THE GAP: ESSAYS By Megan E. Mericle, B.A. A Thesis Submitted in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree of Master of Fine Arts in Creative Writing University of Alaska Fairbanks May 2017 APPROVED: Daryl Farmer, Committee Chair Sarah Stanley, Committee Co-Chair Gerri Brightwell, Committee Member Eileen Harney, Committee Member Richard Carr, Chair Department of English Todd Sherman, Dean College o f Liberal Arts Michael Castellini, Dean of the Graduate School Abstract Sparks Across the Gap is a collection of creative nonfiction essays that explores the humanity and artistry behind topics in the sciences, including black holes, microbes, and robotics. Each essay acts a bridge between the scientific and the personal. I examine my own scientific inheritance and the unconventional relationship I have with the field of science, searching for ways to incorporate research into my everyday life by looking at science and technology through the lens of my own memory. I critique issues that affect the culture of science, including female representation, the ongoing conflict with religion and the problem of separating individuality from collaboration. Sparks Across the Gap is my attempt to parse the confusion, hybridity and interconnectivity of living in science. iii iv Dedication This manuscript is dedicated to my mother and father, who taught me to always seek knowledge with compassion. v vi Table of Contents Page Title Page......................................................................................................................................................i -

EXTENSIONS of REMARKS October 21, 1998 EXTENSIONS of REMARKS

27662 EXTENSIONS OF REMARKS October 21, 1998 EXTENSIONS OF REMARKS TRIBUTE TO THE LATE CONGRESS Washington Post, and the New York Times, tional rights of free speech and association MAN, GARRY BROWN, 1923--1998 Speaker GINGRICH, Majority Leader RICHARD and the right to freely contract for goods and ARMEY, Majority Whip TOM DELAY and House services no longer exist if you are registered HON. FRED UPTON Republican Chairman JOHN BOEHNER either as a Democrat. In fact, you may be sum OF MICHIGAN themselves called or instructed others to call moned before a Congressional Committee to member companies of the Electronics Alliance IN THE HOUSE OF REPRESENTATIVES explain all of your business dealings. This new Industry (EIA) and demand that EIA break its 1990's McCarthyism is a way of life for the Tuesday, October 20, 1998 contract with former Democratic Congressman Republican party. Light must be shed on it Mr. UPTON. Mr. Speaker, many of you may Dave McCurdy and hire a Republican as its and it must be stopped. not have heard of the passing a few weeks new president. In case that was not sufficient Let me provide another example about how ago of our former colleague, Congressman warning, the Republican leadership then re this Congress is punishing people for being Garry Brown, who represented southwest moved legislation to implement the World In Democrats or having the audacity to hire Michigan. Through more than a decade of tellectual Property Organization Act from the Democrats to work for them. Last week Chair service in the House of Representatives, floor schedule and told EIA it was to "send a man JOE BARTON of the Oversight and Inves Garry Brown will be remembered as an am message" that McCurdy and other Democrats tigations Subcommittee of the Commerce bassador from a more genteel era of politics. -

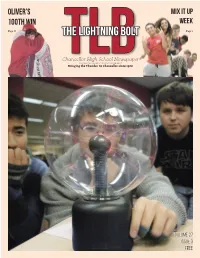

The Lightning Bolt Page 2

Oliver’s Mix It Up 100th win Week Page 17 The Lightning Bolt Page 2 Chancellor High School Newspaper TLB6300 Harrison Road, Fredericksburg, VA 22407 Bringing the Thunder to Chancellor since 1988 Volume 27 Issue 3 FREE 1 November 2014 what IS HAPPENING? Photo by Neil Schubel Neil Photo by Kids flocked to Mix It Up tables during lunch to take their pledge. Mix It Up week challenges kids to identify, cross and challenge social boundaries. Many students took thier pledge to mix it up in the week of November 10th till the 14th. Photo by Yearbook Staff Yearbook Photo by Photo by Neil Schubel Neil Photo by Schubel Neil Photo by Schubel Neil Photo by Tyler Jacobs models his painted Kenneth Ryan was spotted in the Jamie Smith in the process of a Joshua Edney jumps in the air in cheek in Mix It Up Week. halls with a fake skull. painted heart in Mix It Up Week. excitement. Photo courtesy of April Kniebbe April of Photo courtesy Nostalgia November! Who remembers the ALS Ice Bucket Challenge? The football coaches certainly do as they accepted the ALS Ice Bucket Challenge this July. A few players dumped the buckets as the team stood around to watch their coaches get ice buckets dumped on their heads. November 2014 2 Contents Editorial By Neil Schubel coming of winter if you look to by Chancellor’s Sociology Class Mrs. Gattie Editor-in-Chief some cases in states like New was also a huge success as near- Adviser It will ruin the happiest of York that are getting up to four ly 800 students took the pledge mornings waking up and realiz- feet of snow). -

From Assimilation to Kalomoira: Satellite Television and Its Place in New York City’S Greek Community

CORE Metadata, citation and similar papers at core.ac.uk Provided by Directory of Open Access Journals © 2011, Global Media Journal -- Canadian Edition Volume 4, Issue 1, pp. 163-178 ISSN: 1918-5901 (English) -- ISSN: 1918-591X (Français) From Assimilation to Kalomoira: Satellite Television and its Place in New York City’s Greek Community Michael Nevradakis University of Texas at Austin, United States Abstract: This paper examines the role that imported satellite television programming from Greece has played in the maintenance and rejuvenation of Greek cultural identity and language use within the Greek-American community of New York City—the largest and most significant in the United States. Four main concepts guide this paper, based on prior theoretical research established in the field of Diaspora studies: authenticity, assertive hybridity, cultural capital, and imagined communities. Satellite television broadcasts from Greece have targeted the audience of the Hellenic Diaspora as an extension of the homeland, and as a result, are viewed as more “authentic” than Diaspora-based broadcasts. Assertive hybridity is exemplified through satellite programming such as reality shows and the emergence of transnational pop stars such as Kalomoira, who was born and raised in New York but attained celebrity status in Greece as the result of her participation on the Greek reality show Fame Story. Finally, satellite television broadcasts from Greece have fostered the formation of a transnational imagined community, linked by the shared viewing of Greek satellite programming and the simultaneous consumption of Greek pop culture and acquisition of cultural capital. All of the above concepts are evident in the emergence of a Greek “café culture” and “sports culture”, mediated by satellite television and visible in the community’s public spaces. -

2013 Winter Athletic Awards Ceremony Wednesday, Ma

The Loomis Chaffee School 2012-2013 Winter Athletic Awards Ceremony Wednesday, March 27, 2013 Alpine Skiing Boys Basketball Girls Basketball Boys Hockey Girls Hockey Boys Swimming Girls Swimming Boys Squash Girls Squash Wrestling Loomis Chaffee Winter Athletic Awards Ceremony Wednesday, March 27, 2013 6:30 p.m. Loomis Dining Hall Tonight’s Program Welcome Remarks: Bob Howe ’80, Athletic Director Alpine Skiing: Jake Leyden Girls Squash: Naomi Appel Boys Squash: Elliot Beck Girls Swimming: Bob DeConinck Boys Swimming: Fred Seebeck Girls Hockey Liz Leyden Boys Hockey John Zavisza Boys Basketball Jim Dargati ‘85 Girls Basketball Adrian Stewart ‘90 Wrestling Ben Haldeman 2012-2013 Winter Athletic Award Winners Alpine Skiing All New England: Tucker Santoro, Sara Corsetti Most Valuable Skiier: Tucker Santoro Coaches’ Award: Theodora Cohen Boys Varsity Basketball All New England: Joe Stortini Coaches’ Award: Durelle Napier Coaches’ Award: Dale Reese Most Valuable Player: Joe Stortini Girls Varsity Basketball All New England: Steph Jones and Abby Pyne Most Valuable Player: Steph Jones Most Improved: Chynna Bailey Coaches’ Award: Brooke Marchitto Boys Varsity Hockey U.S.HR Prep School Player of the Year Danny Tirone All New England Team: Danny Tirone Most Valuable Player: Danny Tirone Coaches’ Award: EJ Culhane Coaches’ Award: Nick Miceli Golden Buoy: Stephen Picard Girls Varsity Hockey Coaches’ Award: Brittany Bugalski Coaches’ Award: Molly Strabley Boys Varsity Squash Most Valuable Player: Alex Steel Most Improved Player: Kevin Cha Coaches’ Award: -

Unit 12 Americans in Indochina

UNIT 12 AMERICANS IN INDOCHINA CHAPTER 1 THE FRENCH IN INDOCHINA.......................................................................................................1 CHAPTER 2 COMMUNISM, GUERRILLAS AND FALLING DOMINOES .....................................................5 CHAPTER 3 ʹSINK OR SWIM, WITH NGO DINH DIEMʹ...................................................................................9 CHAPTER 4 FIGHTING AGAINST GUERRILLAS: THE STRATEGIC HAMLET PROGRAM...................12 CHAPTER 5 EXIT NGO DINH DIEM AND THE GULF OF TONKIN INCIDENT.......................................16 CHAPTER 6 FIGHTING A GUERRILLA WAR...................................................................................................22 CHAPTER 7 HOW MY LAI WAS PACIFIED ......................................................................................................25 CHAPTER 8 THE TET OFFENSIVE .....................................................................................................................30 CHAPTER 9 VIETNAMIZATION ........................................................................................................................36 CHAPTER 10 THE WAR IS FINISHED.................................................................................................................40 CHAPTER 11 WAS THE ʹWHOLE THING A LIEʹ OR A ʹNOBLE CRUSADEʹ...............................................43 by Thomas Ladenburg, copyright, 1974, 1998, 2001, 2007 100 Brantwood Road, Arlington, MA 02476 781-646-4577 [email protected] Page -

Little Boy, the Antichristchild. the Beast in the Nuclear

UTTLE BOY, THE ANTICHRISTCHILD: THE BEAST IN THE NUCLEAR AGE EDDIE TAFO YA University of New México, USA (Resumen) El presente trabajo intenta demostrar cómo el "anticristo" de John Divine está hoy presente en la bomba atómica. La bomba no sólo ha atraido la atención de h'deres y empresas mundiales quienes la cuestionan y se preguntan "¿Quién puede luchar contra ella?" sino que además ejerce un control totalitario sobre el planeta. Al igual que el "corazón" de John, la bomba en un principio devolvió la paz a un mundo caótico, hizo iimumerables promesas y dijo numerosas blasfemias antes de asumir el papel del dios de la era moderna. The Wonum, the Beast and the Voice in the WUdaness In 1964, Robert Mosely stalked, stabbed, raped, and murdered Kitty Genovese on a New York City Street while 38 people listened to her cries and did nothing. Some even puUed chairs up to their windows to watch the horror.' While this is a sad commentary on U.S. culture, it is a paradigm theological moment. It is the Parable of the Good Samaritan transplanted from Luke's Gospel into modern times. On a theological level, the cries were not merely those of Kitty Genovese but the cries of the eternal Other, the person in need. While Christianity smce the time of Constantino has been a tool for the oppressing of gays, women, non-capitalists, and others, there is a persisten! line of thought which advócales that Jesús' message was not as much a matter of orthodoxy as it is a matter of orthopraxies; it is not so much a religión of repentance as it is a religión of divine duty predicated on listening and responding to the voice of the Other. -

ROMA SURRECTA: Portrait of a Counterinsurgent Power, 216 BC - AD 72

University of Pennsylvania ScholarlyCommons CUREJ - College Undergraduate Research Electronic Journal College of Arts and Sciences 5-2011 ROMA SURRECTA: Portrait of a Counterinsurgent Power, 216 BC - AD 72 Emerson T. Brooking University of Pennsylvania, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: https://repository.upenn.edu/curej Part of the Ancient History, Greek and Roman through Late Antiquity Commons, Comparative Politics Commons, Military History Commons, and the Other Political Science Commons Recommended Citation Brooking, Emerson T., "ROMA SURRECTA: Portrait of a Counterinsurgent Power, 216 BC - AD 72" 01 May 2011. CUREJ: College Undergraduate Research Electronic Journal, University of Pennsylvania, https://repository.upenn.edu/curej/145. This paper is posted at ScholarlyCommons. https://repository.upenn.edu/curej/145 For more information, please contact [email protected]. ROMA SURRECTA: Portrait of a Counterinsurgent Power, 216 BC - AD 72 Abstract This study evaluates the military history and practice of the Roman Empire in the context of contemporary counterinsurgency theory. It purports that the majority of Rome’s security challenges fulfill the criteria of insurgency, and that Rome’s responses demonstrate counterinsurgency proficiency. These assertions are proven by means of an extensive investigation of the grand strategic, military, and cultural aspects of the Roman state. Fourteen instances of likely insurgency are identified and examined, permitting the application of broad theoretical precepts -

Don't Bungle the Talks

O C V ΓΡΑΦΕΙ ΤΗΝ ΙΣΤΟΡΙΑ Bringing the news ΤΟΥ ΕΛΛΗΝΙΣΜΟΥ to generations of ΑΠΟ ΤΟ 1915 The National Herald Greek Americans c v A wEEkLy GREEk AmERICAN PUBLICATION www.thenationalherald.com VOL. 13, ISSUE 676 September 25-October 1, 2010 $1.50 Peterson’s Chrysostomos Warns Christofias: Don't Bungle The Talks Simple Archbishops Sees No Solution, Success Says Church Is Not That Rich By Theodore Kalmoukos Chrysostomos said that, “The TNH Staff Writer Turks want everything, they put Formula forth maximalist positions. They BOSTON - “The national issue speak of two Peoples, two of Cyprus is not going well at States, two Nations; you under - Americans: Save, all” His Beatitude Archbishop stand that we are not heading Chrysostomos of Cyprus said in towards a solution.” Christofias Sacrifice, Choose, an exclusive interview to The has been unable to make any National Herald. The Arch - headway with Turkish leaders Hike Revenues bishop sent a clear message to since taking office on Feb. 2008, Cypriot President Demetris despite making unilateral con - NEW YORK – When self-made Christofias, who was in New cessions. Greek Cypriots in a billionaire Pete Peterson told an York attending the United Na - 2004 referendum defeated the audience at a Leadership 100 tions opening ceremonies “not so-called Annan Plan for re-uni - meeting here Sept. 9 that that to accept an international meet - fication, named for former U.N. American Dream was fading, he ing before the internal problems leader Koffi Annan, and also laid out a grim scenario that with the Turkish-Cypriots are re - Christofias’ critics said he is giv - portrayed the United States slip - solved.” The Archbishop said if ing away too much and that part ping into an unrecoverable eco - that happened, “The solution of his ideas mimic the rejected nomic crisis for the simple reason which will be imposed will be plan. -

Utah's Grand Staircase: the Right Path to Wilderness Preservation?

Brigham Young University Law School BYU Law Digital Commons Faculty Scholarship 1-1-1999 Utah's Grand Staircase: The Right Path to Wilderness Preservation? James R. Rasband BYU Law Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.law.byu.edu/faculty_scholarship Part of the Land Use Law Commons, and the Natural Resources Law Commons Recommended Citation James R. Rasband, Utah's Grand Staircase: The Right Path to Wilderness Preservation?, 70 U. Cᴏʟᴏ. L. Rᴇᴠ., 483 (1999). This Article is brought to you for free and open access by BYU Law Digital Commons. It has been accepted for inclusion in Faculty Scholarship by an authorized administrator of BYU Law Digital Commons. For more information, please contact [email protected]. UTAH'S GRAND STAIRCASE: THE RIGHT PATH TO WILDERNESS PRESERVATION? JAMES R. RASBAND* INTRODUCTION On September 18, 1996, President Clinton stood at the South Rim of the Grand Canyon in Arizona and exercised his broad authority under the Antiquities Act' to set aside 1.7 million acres of public land, northward in Utah, as the Grand Staircase- Escalante National Monument ("the Monument" or "Grand Staircase").2 Securely separated from Utah by the wondrous * Associate Professor of Law, J. Reuben Clark Law School, Brigham Young University. I am grateful to Kevin Worthen and Ester Rasband for their thoughtful comments on earlier drafts. I am also grateful to Troy Smith and Patrick Malone for their able research assistance. Comments can be directed to rasbandj@ lawgate.byu.edu. 1. 16 U.S.C. § 431 (1994). Section