Authors Pseudonyms in the Seventeenth Century: the Case of Gaspar Scioppio

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Lapp 1 the Victorian Pseudonym and Female Agency Research Thesis

Lapp 1 The Victorian Pseudonym and Female Agency Research Thesis Presented in partial fulfillment of the requirements for graduation with research distinction in English in the undergraduate colleges of The Ohio State University by Anna Lapp The Ohio State University April 2015 Project Advisor: Professor Robyn Warhol, Department of English Lapp 2 Chapter One: The History of the Pseudonym Anonymity disguises information. For authors, disguised or changed names shrouds their circumstance and background. Pseudonyms, or pen names, have been famously used to disguise one’s identity. The word’s origin—pseudṓnymon—means “false name”. The nom de plume allows authors to conduct themselves without judgment attached to their name. Due to an author’s sex, personal livelihood, privacy, or a combination of the three, the pen name achieves agency through its protection. To consider the overall protection of the pseudonym, I will break down the components of a novel’s voice. A text is written by a flesh-and-blood, or actual, author. Second, an implied author or omnipresent figure of agency is present throughout the text. Finally, the narrator relates the story to the readers. The pseudonym offers freedom for the actual author because the author becomes two-fold—the pseudonym and the real person, the implied author and the actual author. The pseudonym can take the place of the implied author by acting as the dominant force of the text without revealing the personal information of the flesh-and-blood author. Carmela Ciuraru, author of Nom de Plume: A (Secret) History of Pseudonyms, claims, “If the authorial persona is a construct, never wholly authentic (now matter how autobiographical the material), then the pseudonymous writer takes this notion to yet another level, inventing a construct of a construct” (xiii-xiv). -

Issues in the Linguistics of Onomastics

Journal of Lexicography and Terminology, Volume 1, Issue 2 Issues in the Linguistics of Onomastics By Vincent M. Chanda School of Humanities and Social Science University of Zambia Email: mchanda@@gmail.com Abstract Names, also called proper names or proper nouns, are very important to mankind that there is no human language without names and, for some types of names, there are written or unwritten naming conventions. The social importance of names is also the reason why onomastics, the study of names, is a multidisciplinary field. After briefly discussing the multidisciplinary nature of onomastics, the article proves the following view stated and proved by many a scholar: proper names have a grammar that includes some grammatical features of common nouns. In so doing, the article shows that, like common nouns, proper names show cross linguistic differences. To prove that names do have a grammar which in some aspects differs from the grammar of common nouns, the article often compares proper names and common nouns. Furthermore, the article uses data from several languages in addition to English. After a bief discussion of orthographic differences between proper names and common nouns, the article focuses on the morphology, both inflectional and lexical, and the syntax of proper names. Key words: Name, common noun, onomastics, multidisciplinary, naming convention, typology of names, anthroponym, inflectional morphology, lexical morphology, derivation, compounding, syntac. 67 Journal of Lexicography and Terminology, Volume 1, Issue 2 1. Introduction Onomastics or onomatology, is the study of proper names. Proper names are terms used as a means of identification of particular unique beings. -

COPYRIGHT in PSEUDONYMOUS and ANONYMOUS WORKS Ronan Deazley and Kerry Patterson

COPYRIGHT IN PSEUDONYMOUS AND ANONYMOUS WORKS Ronan Deazley and Kerry Patterson 1. Introduction The use of pseudonyms has a long-standing tradition in newspaper and magazine publishing. The Economist, for example, operates a well-established practice of editorial anonymity in that all of their columnists publish under pseudonyms such as Bagehot, Lexington and Schumpeter.1 This Guidance explains what is stated in the law about the authorship of works made under a pseudonym, and about the ownership of copyright in works created both anonymously and under a pseudonym, and considers the implications these presumptions have for rights clearance projects. 2. In Practice If the name of the publisher appears How is the work credited? on the work, the publisher is It is anonymous presumed to be the owner of the copyright until there is evidence to the contrary. A pseudonym is used No The author is presumed to be the owner of the copyright – ownership Is the author commonly of copyright depends on relationship Yes known by this pseudonym? between author and publisher Ask the publisher for information on Don’t Know the author, but if they cannot provide this information, the publisher is presumed to be the copyright owner. Within the pages of the Edwin Morgan Scrapbooks examined as part of this research project, there is one letter, cut from a newspaper letters page, which has been published under a pseudonym: Navigator. In it, the writer relates the experience of seeing a mysterious ‘aircraft’/UFO over Glasgow. So, what do the legal presumptions -

Root Definition Examples Origin Sed Sit Sedentary, Sediment, Sedan

Word Within the Word List #8 Root Definition Examples Origin sed sit sedentary, sediment, sedan, sedative, sedate, Latin supersede, assiduous, insidious leg read legible, legend, illegible, legendary, legibility, Latin alleged anim mind equanimity, animal, animated, magnanimous Latin tort twist contorted, torture, retort, distort, tortilla Latin nym name homonym, acronym, pseudonym, Greek anonymous sanct holy sanctity, sanctimonious, sanctuary, Latin unsanctioned, sanctify meta change metamorphosis, metaphor, metaphysics, Greek metabolism petr rock petrify, petroleum, petroglyph, petrochemical Latin mir wonder miracle, mirage, mirror, admire Latin man hand manual, manicure, manipulate, manacles Latin rect right correct, rectify, direct, rectangle, erect Latin volv roll revolve, involved, convoluted, revolution Latin demi half demigod, demitasse, demimonde, demirep Latin retro backward retroactive, retrogress, retrospection, retrofit Latin sens feel sense, sensitive, sensation, sensory, Latin extrasensory, insensate fy make fortify, rectify, horrify, solidify, transmogrify, Latin sanctify, pacify ocul eye binocular, monocular, ocular, oculist, Latin oculomotor nerve, oculometer cur care for cure, curator, curative, cure-all, sinecure, Latin secure, curate ultra beyond ultramarine, ultraconservative, ultraviolet Latin oid appearance android, asteroid, adenoid Greek gest carry gestation, digest, ingest, congestion, gesture Latin apt fit adapt, aptitude, maladapted, adaptation Latin tact touch tactile, contact, tactful, intact Latin voc voice vocal, sotto voce, invocation, vocabulary Latin rid laugh ridicule, deride, ridiculous, derision Latin Word Within the Word List #8 Using the context clues from the sentence and your understanding of the root, define the underlined words in the following sentences. 1. His sedentary job left him weak and out of shape. 2. The college student’s handwriting was illegible. 3. The bitter animosity made him lose his equanimity. -

Stakeholder Expectations of Islamic Education

Portland State University PDXScholar Dissertations and Theses Dissertations and Theses 6-8-2018 Stakeholder Expectations of Islamic Education Julia Marie Ahmed Portland State University Follow this and additional works at: https://pdxscholar.library.pdx.edu/open_access_etds Part of the Educational Leadership Commons, and the Islamic Studies Commons Let us know how access to this document benefits ou.y Recommended Citation Ahmed, Julia Marie, "Stakeholder Expectations of Islamic Education" (2018). Dissertations and Theses. Paper 4395. https://doi.org/10.15760/etd.6279 This Dissertation is brought to you for free and open access. It has been accepted for inclusion in Dissertations and Theses by an authorized administrator of PDXScholar. Please contact us if we can make this document more accessible: [email protected]. Stakeholder Expectations of Islamic Education by Julia Marie Ahmed A dissertation submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Education in Educational Leadership: Curriculum and Instruction Dissertation Committee: Susan Lenski, Chair Swapna Mukhopadhyay Dannelle Stevens Sharon Carstens Portland State University 2018 © 2018 Julia Marie Ahmed STAKEHOLDER EXPECTATIONS OF ISLAMIC EDUCATION i Abstract Teachers and parents make considerable sacrifices to affiliate themselves with Islamic schools. As they commit to Islamic education, they acquire certain expectations that they want their school to fulfill. The purpose of this study was to explore the academic, social, and cultural expectations -

USA V. Ishmael Jones: Govt Motion to Name Defendant by Pseudonym

IN THE UNITED STATES DISTRICT COURT FILED FOR THE EASTERN DISTRICT OF VIRGINIA ALEXANDRIA DIVISION 2010 JUL -^ P 3s U"l UNITED STATES OF AMERICA, ) ) Civil Action No. Plaintiff, ) ) v. ) ) ISHMAEL JONES, a pen name, ) ) Defendant. ) PLAINTIFF UNITED STATES1 MOTION FOR IMMEDIATE RELIEF TO NAME DEFENDANT BY PSEUDONYM Plaintiff the United States, acting through undersigned counsel, moves the Court for an Order granting it permission to sue defendant by the pseudonym under which he published a book. Defendant is a former covert officer for the Central Intelligence Agency ("CIA") whose affiliation with the CIA remains classified. The United States requests permission to sue him in pseudonym to protect from public disclosure defendant's affiliation with the CIA. Consistent with this request, the United States also requests that the Court order that the parties and any third party who makes a filing in this case shall redact defendant's true name and any identifying information from all documents filed on the public record, and that service of the complaint be made by a Deputy United States Marshal. In support of this Motion, the attention of the Court is respectfully invited to the Memorandum filed herewith and Declaration of Ralph S. DiMaio, Information Review Officer, National Clandestine Service, Central Intelligence Agency, filed herewith. Dated: Respectfully Submitted, TONY WEST NEIL H. MACBRIDE Assistant Attorney General United States Attorney VINCENT M. GARVEY Deputy Branch Director Federal Programs Branch By: MARCIA BERMAN KEVIN J.MlKOLASHEK Senior Counsel Assistant United States Attorney Federal Programs Branch 2100 Jamieson Avenue U.S. Department of Justice Alexandria, VA 22314 20 Massachusetts Ave., N.W. -

Nameauth — Name Authority Mechanism for Consistency in Text and Index∗

nameauth — Name authority mechanism for consistency in text and index∗ Charles P. Schaum† Released 2021/02/27 Abstract The nameauth package automates the correct formatting and indexing of names for professional writing. This aids the use of a name authority and the editing process without needing to retype name references. Contents 1 Quick Start2 2.7.2 Advanced Features.. 54 1.1 Introduction..........2 2.8 Name Decisions........ 57 1.2 How to Use the Manual...3 2.8.1 Making Decisions... 58 1.3 Task Dashboard.......4 2.8.2 Testing Decisions... 61 1.4 Basic Name Concepts....5 2.9 Alternate Name Macros... 64 1.5 Basic Interface........6 2.10 Longer Examples....... 67 1.6 Quick Interface........9 2.10.1 Hooks: Intro..... 67 1.7 Macro Overview....... 12 2.10.2 Hooks: Life Dates.. 68 1.8 Various Hints......... 13 2.10.3 Hooks: Advanced... 69 2.10.4 Customization.... 77 2 Detailed Usage 17 2.11 Technical Notes........ 79 2.1 Package Options....... 17 2.11.1 General........ 79 2.2 Naming Macros........ 21 2.11.2 Package Warnings.. 80 2.2.1 \Name and \Name* .. 21 2.11.3 Debugging/Errors.. 81 2.2.2 Forenames: \FName .. 22 2.11.4 Obsolete Syntax... 84 2.2.3 Variant Names.... 23 2.11.5 Name Patterns.... 85 2.3 Language Topics....... 25 2.11.6 Active Unicode.... 86 2.3.1 Affixes......... 25 2.11.7 LATEX Engines.... 88 2.3.2 Listing by Surname. 26 2.3.3 Eastern Names.... 26 3 Implementation 91 2.3.4 Particles....... -

A Study of How Myanmar Authors Take a Pen-Name

A Study of How Myanmar Authors Take a Pen-name Khin Thida Latt Abstract It is found what foreign authors write under a pseudonym is rare and they become famous for their real names. And, some also use a pen-name so that they may want to be secret themselves and with another name, they may want to create literature different from one they get used to writing. Nevertheless almost all Myanmar authors take a pen-name. It is very interesting for researchers even how began the practice Myanmar authors write under the pseudonym. The objective of this paper is to make researchers and librarians know how the Myanmar authors in the history of Myanmar literature used their interesting pen-name. This research covers (45) selected Myanmar authors take a pen-name. The method used in this paper is literature survey method. Key words: pseudonym; rare; real name; pen-name. Introduction Tetkatho Htin Gyi is the foremost author who wrote about pen-names in Myanmar literature. Saya Tetkatho Htin Gyi was the last chairman for Burma Research Society (1980), Director of Sarpay Beikman, National Literature Laureate for 1992, life time Achievement in Myanmar Literature by the Pakkoku U Ohn Pe literary prize laureate (Arts) (2003). He wrote pseudonym of Tetkatho Htin Gyi in the journal of Burma Writers Association, Vol.3. According to his friend‟s question how to get his pen-name, he explained about it and he was interested in pen-names. It is presented in this paper how the (45) writers took their pen-names differently. In the paper, the pen-names of (45) writers -

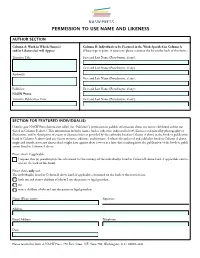

Permission to Use Name and Likeness

PERMISSION TO USE NAME AND LIKENESS AUTHOR SECTION Column A: Work in Which Name(s) Column B: Individuals to be Featured in the Work Specified in Column A and/or Likeness(es) will Appear (Please type or print. If necessary, please continue the list on the back of this form.) Tentative Title: First and Last Name (Pseudonym, if any): First and Last Name (Pseudonym, if any): Author(s): First and Last Name (Pseudonym, if any): Publisher: First and Last Name (Pseudonym, if any): NASW Press Tentative Publication Date: First and Last Name (Pseudonym, if any): SECTION FOR FEATURED INDIVIDUAL(S) I hereby give NASW Press (hereinafter called the “Publisher”) permission to publish information about my minor child(ren) and/or me (listed in Column B above). This information includes names (unless otherwise indicated below), likenesses obtained by photography or illustration, and/or description of events or characteristics as provided by the author(s) listed in Column A above in the book or publication listed in Column A above (and any future revisions, editions, and formats). I release the author(s) and publisher listed in Column A above, singly and jointly, from any claims that I might have against them now or at a later date resulting from the publication of the book or publi- cation listed in Column A above. Please check if applicable: I request that (a) pseudonym(s) be substituted for the name(s) of the individual(s) listed in Column B above (and, if applicable, contin- ued on the back of this form). Please check only one: The individual(s) listed in Column B above (and, if applicable, continued on the back of this form) is/are: both me and minor children of whom I am the parent or legal guardian me minor children of whom I am the parent or legal guardian Name (Please print): Signature: Address: Email Address: Telephone: Date: Please return this form to NASW Press, 750 First Street, NE, Suite 700, Washington, D.C. -

Judgments for Children

LAW RESEARCH BRIEFING #18 SEPTEMBER 2020 Judgments for Children Professor Kathryn Hollingsworth† Professor Helen Stalford* † Newcastle Law School, Newcastle University, UK * Liverpool Law School, University of Liverpool, UK This briefing is based on research reported in Stalford, H and Hollingsworth, K ‘“This case is about you and your future”: Towards Judgments for Children’ (2020) 83(5) Modern Law Review 1030-1058. This work developed from the Children’s Rights Judgments Project: www.CRJudgment.uk A handful of ‘child-friendly’ judgments have emerged in the UK in recent years. This briefing examines why the form and presentation of judicial decisions is an important aspect of children’s access to justice, and why judges have a duty to enhance children’s status and capacities as legal citizens through judgment writing. We identify four potential functions of judgments written for children (communicative, developmental, instructive and legally transformative), and call for greater attention to be paid to how judgments are constructed and conveyed with a view to promoting children’s access to justice. Introduction 1. It is now well recognised that adaptations need to be made to legal proceedings that involve children, so that their distinct needs and vulnerabilities can be accommodated. This notion is commonly referred to as ‘Child Friendly Justice’.1 However, in most justice proceedings, efforts to render the process ‘child friendly’ almost entirely focus on the procedures for the treatment of children pre-decision, particularly in the context of hearing evidence and enabling children to ‘feel’ part of the proceedings. But there is less focus, and much less clarity and certainty, on how the outcomes of legal proceedings – and in particular, legal judgments – are and should be communicated to the child. -

Personal Name Policy: from Theory to Practice

Dysertacje Wydziału Neofilologii UAM w Poznaniu 4 Justyna B. Walkowiak Personal Name Policy: From Theory to Practice Wydział Neofilologii UAM w Poznaniu Poznań 2016 Personal Name Policy: From Theory to Practice Dysertacje Wydziału Neofilologii UAM w Poznaniu 4 Justyna B. Walkowiak Personal Name Policy: From Theory to Practice Wydział Neofilologii UAM w Poznaniu Poznań 2016 Projekt okładki: Justyna B. Walkowiak Fotografia na okładce: © http://www.epaveldas.lt Recenzja: dr hab. Witold Maciejewski, prof. Uniwersytetu Humanistycznospołecznego SWPS Copyright by: Justyna B. Walkowiak Wydanie I, Poznań 2016 ISBN 978-83-946017-2-0 *DOI: 10.14746/9788394601720* Wydanie: Wydział Neofilologii UAM w Poznaniu al. Niepodległości 4, 61-874 Poznań e-mail: [email protected] www.wn.amu.edu.pl Table of Contents Preface ............................................................................................................ 9 0. Introduction .............................................................................................. 13 0.1. What this book is about ..................................................................... 13 0.1.1. Policies do not equal law ............................................................ 14 0.1.2. Policies are conscious ................................................................. 16 0.1.3. Policies and society ..................................................................... 17 0.2. Language policy vs. name policy ...................................................... 19 0.2.1. Status planning ........................................................................... -

Novel Pseudonym Generation for Secured Privacy in Vehicular Adhoc Networks Swapna.Ch ,Vijayashree R Budyal

International Journal of Recent Technology and Engineering (IJRTE) ISSN: 2277-3878, Volume-8 Issue-4S5, December 2019 Novel Pseudonym Generation for Secured Privacy in Vehicular Adhoc Networks Swapna.ch ,Vijayashree R Budyal Abstract: Intelligent Transport Communication (ITC) has Privacy to the vehicles is one of the important parameter gained popularity in the present day scenario, where in communication. During communication, the malicious communication in vehicle is possible and it can be between nodes should not know the real identity of the source node Vehicle to Vehicle or Vehicle to Infrastructure. Security is one of from where the information being transmitted. If the the important issue in Vehicular Adhoc Networks (VANETS) and some of the main features of security are Privacy, malicious node identifies the real identity of the vehicle Confidentiality, Integrity, Authentication and Non-repudiation. from where message is being transmitted, then there may be In the present scenario privacy along with security is considered the possibility of various attacks. These attacks may be due to be one of the important factor, since the malicious nodes can to internal or external attackers. Internal attackers are the attack the vehicles at any point of time during communication. attackers who are in the network and participate in the Thus , Secured Privacy in Vehicular Adhoc Networks by communication. External attackers are the attackers who are Generating Efficient Pseudonym based on Weil Pair Algorithm outside the network but absorb and take messages and may (SPGPWP), is developed to address secured privacy in VANET’s try to decrypt the messages. In our proposed work Secured .