Bernard O'dowd, Wafting Him to London, Setting Him Down in the Same Spots Where Mr

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Using Concrete Scales: a Practical Framework for Effective Visual Depiction of Complex Measures Fanny Chevalier, Romain Vuillemot, Guia Gali

Using Concrete Scales: A Practical Framework for Effective Visual Depiction of Complex Measures Fanny Chevalier, Romain Vuillemot, Guia Gali To cite this version: Fanny Chevalier, Romain Vuillemot, Guia Gali. Using Concrete Scales: A Practical Framework for Effective Visual Depiction of Complex Measures. IEEE Transactions on Visualization and Computer Graphics, Institute of Electrical and Electronics Engineers, 2013, 19 (12), pp.2426-2435. 10.1109/TVCG.2013.210. hal-00851733v1 HAL Id: hal-00851733 https://hal.inria.fr/hal-00851733v1 Submitted on 8 Jan 2014 (v1), last revised 8 Jan 2014 (v2) HAL is a multi-disciplinary open access L’archive ouverte pluridisciplinaire HAL, est archive for the deposit and dissemination of sci- destinée au dépôt et à la diffusion de documents entific research documents, whether they are pub- scientifiques de niveau recherche, publiés ou non, lished or not. The documents may come from émanant des établissements d’enseignement et de teaching and research institutions in France or recherche français ou étrangers, des laboratoires abroad, or from public or private research centers. publics ou privés. Using Concrete Scales: A Practical Framework for Effective Visual Depiction of Complex Measures Fanny Chevalier, Romain Vuillemot, and Guia Gali a b c Fig. 1. Illustrates popular representations of complex measures: (a) US Debt (Oto Godfrey, Demonocracy.info, 2011) explains the gravity of a 115 trillion dollar debt by progressively stacking 100 dollar bills next to familiar objects like an average-sized human, sports fields, or iconic New York city buildings [15] (b) Sugar stacks (adapted from SugarStacks.com) compares caloric counts contained in various foods and drinks using sugar cubes [32] and (c) How much water is on Earth? (Jack Cook, Woods Hole Oceanographic Institution and Howard Perlman, USGS, 2010) shows the volume of oceans and rivers as spheres whose sizes can be compared to that of Earth [38]. -

Detection of PAH and Far-Infrared Emission from the Cosmic Eye

Accepted for publication in ApJ A Preprint typeset using LTEX style emulateapj v. 08/22/09 DETECTION OF PAH AND FAR-INFRARED EMISSION FROM THE COSMIC EYE: PROBING THE DUST AND STAR FORMATION OF LYMAN BREAK GALAXIES B. Siana1, Ian Smail2, A. M. Swinbank2, J. Richard2, H. I. Teplitz3, K. E. K. Coppin2, R. S. Ellis1, D. P. Stark4, J.-P. Kneib5, A. C. Edge2 Accepted for publication in ApJ ABSTRACT ∗ We report the results of a Spitzer infrared study of the Cosmic Eye, a strongly lensed, LUV Lyman Break Galaxy (LBG) at z =3.074. We obtained Spitzer IRS spectroscopy as well as MIPS 24 and 70 µm photometry. The Eye is detected with high significance at both 24 and 70 µm and, when including +4.7 11 a flux limit at 3.5 mm, we estimate an infrared luminosity of LIR = 8.3−4.4 × 10 L⊙ assuming a magnification of 28±3. This LIR is eight times lower than that predicted from the rest-frame UV properties assuming a Calzetti reddening law. This has also been observed in other young LBGs, and indicates that the dust reddening law may be steeper in these galaxies. The mid-IR spectrum shows strong PAH emission at 6.2 and 7.7 µm, with equivalent widths near the maximum values observed in star-forming galaxies at any redshift. The LP AH -to-LIR ratio lies close to the relation measured in local starbursts. Therefore, LP AH or LMIR may be used to estimate LIR and thus, star formation rate, of LBGs, whose fluxes at longer wavelengths are typically below current confusion limits. -

Close-Up View of a Luminous Star-Forming Galaxy at Z = 2.95 S

Close-up view of a luminous star-forming galaxy at z = 2.95 S. Berta, A. J. Young, P. Cox, R. Neri, B. M. Jones, A. J. Baker, A. Omont, L. Dunne, A. Carnero Rosell, L. Marchetti, et al. To cite this version: S. Berta, A. J. Young, P. Cox, R. Neri, B. M. Jones, et al.. Close-up view of a luminous star- forming galaxy at z = 2.95. Astronomy and Astrophysics - A&A, EDP Sciences, 2021, 646, pp.A122. 10.1051/0004-6361/202039743. hal-03147428 HAL Id: hal-03147428 https://hal.archives-ouvertes.fr/hal-03147428 Submitted on 19 Feb 2021 HAL is a multi-disciplinary open access L’archive ouverte pluridisciplinaire HAL, est archive for the deposit and dissemination of sci- destinée au dépôt et à la diffusion de documents entific research documents, whether they are pub- scientifiques de niveau recherche, publiés ou non, lished or not. The documents may come from émanant des établissements d’enseignement et de teaching and research institutions in France or recherche français ou étrangers, des laboratoires abroad, or from public or private research centers. publics ou privés. A&A 646, A122 (2021) Astronomy https://doi.org/10.1051/0004-6361/202039743 & c S. Berta et al. 2021 Astrophysics Close-up view of a luminous star-forming galaxy at z = 2.95? S. Berta1, A. J. Young2, P. Cox3, R. Neri1, B. M. Jones4, A. J. Baker2, A. Omont3, L. Dunne5, A. Carnero Rosell6,7, L. Marchetti8,9,10 , M. Negrello5, C. Yang11, D. A. Riechers12,13, H. Dannerbauer6,7, I. -

Ast110fall2015-Labmanual.Pdf

2015/2016 (http://astronomy.nmsu.edu/astro/Ast110Fall2015.pdf) 1 2 Contents 1IntroductiontotheAstronomy110Labs 5 2TheOriginoftheSeasons 21 3TheSurfaceoftheMoon 41 4ShapingSurfacesintheSolarSystem:TheImpactsofCometsand Asteroids 55 5IntroductiontotheGeologyoftheTerrestrialPlanets 69 6Kepler’sLawsandGravitation 87 7TheOrbitofMercury 107 8MeasuringDistancesUsingParallax 121 9Optics 135 10 The Power of Light: Understanding Spectroscopy 151 11 Our Sun 169 12 The Hertzsprung-Russell Diagram 187 3 13 Mapping the Galaxy 203 14 Galaxy Morphology 219 15 How Many Galaxies Are There in the Universe? 241 16 Hubble’s Law: Finding the Age of the Universe 255 17 World-Wide Web (Extra-credit/Make-up) Exercise 269 AFundamentalQuantities 271 BAccuracyandSignificantDigits 273 CUnitConversions 274 DUncertaintiesandErrors 276 4 Name: Lab 1 Introduction to the Astronomy 110 Labs 1.1 Introduction Astronomy is a physical science. Just like biology, chemistry, geology, and physics, as- tronomers collect data, analyze that data, attempt to understand the object/subject they are looking at, and submit their results for publication. Along thewayas- tronomers use all of the mathematical techniques and physics necessary to understand the objects they examine. Thus, just like any other science, a largenumberofmath- ematical tools and concepts are needed to perform astronomical research. In today’s introductory lab, you will review and learn some of the most basic concepts neces- sary to enable you to successfully complete the various laboratory exercises you will encounter later this semester. When needed, the weekly laboratory exercise you are performing will refer back to the examples in this introduction—so keep the worked examples you will do today with you at all times during the semester to use as a refer- ence when you run into these exercises later this semester (in fact, on some occasions your TA might have you redo one of the sections of this lab for review purposes). -

12 Strong Gravitational Lenses

12 Strong Gravitational Lenses Phil Marshall, MaruˇsaBradaˇc,George Chartas, Gregory Dobler, Ard´ısEl´ıasd´ottir,´ Emilio Falco, Chris Fassnacht, James Jee, Charles Keeton, Masamune Oguri, Anthony Tyson LSST will contain more strong gravitational lensing events than any other survey preceding it, and will monitor them all at a cadence of a few days to a few weeks. Concurrent space-based optical or perhaps ground-based surveys may provide higher resolution imaging: the biggest advances in strong lensing science made with LSST will be in those areas that benefit most from the large volume and the high accuracy, multi-filter time series. In this chapter we propose an array of science projects that fit this bill. We first provide a brief introduction to the basic physics of gravitational lensing, focusing on the formation of multiple images: the strong lensing regime. Further description of lensing phenomena will be provided as they arise throughout the chapter. We then make some predictions for the properties of samples of lenses of various kinds we can expect to discover with LSST: their numbers and distributions in redshift, image separation, and so on. This is important, since the principal step forward provided by LSST will be one of lens sample size, and the extent to which new lensing science projects will be enabled depends very much on the samples generated. From § 12.3 onwards we introduce the proposed LSST science projects. This is by no means an exhaustive list, but should serve as a good starting point for investigators looking to exploit the strong lensing phenomenon with LSST. -

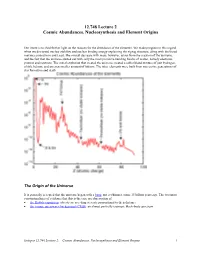

12.748 Lecture 2 Cosmic Abundances, Nucleosynthesis and Element Origins

12.748 Lecture 2 Cosmic Abundances, Nucleosynthesis and Element Origins Our intent is to shed further light on the reasons for the abundance of the elements. We made progress in this regard when we discussed nuclear stability and nuclear binding energy explaining the zigzag structure, along with the broad maxima around Iron and Lead. The overall decrease with mass, however, arises from the creation of the universe, and the fact that the universe started out with only the most primitive building blocks of matter, namely electrons, protons and neutrons. The initial explosion that created the universe created a rather bland mixture of just hydrogen, a little helium, and an even smaller amount of lithium. The other elements were built from successive generations of star formation and death. The Origin of the Universe It is generally accepted that the universe began with a bang, not a whimper, some 15 billion years ago. The two most convincing lines of evidence that this is the case are observation of • the Hubble expansion: objects are receding at a rate proportional to their distance • the cosmic microwave background (CMB): an almost perfectly isotropic black-body spectrum Isotopes 12.748 Lecture 2: Cosmic Abundances, Nucleosynthesis and Element Origins 1 In the initial fraction of a second, the temperature is so hot that even subatomic particles like neutrons, electrons and protons fall apart into their constituent pieces (quarks and gluons). These temperatures are well beyond anything achievable in the universe since. As the fireball expands, the temperature drops, and progressively higher-level particles are manufactured. By the end of the first second, the temperature has dropped to a mere billion degrees or so, and things are starting to get a little more normal: electrons, neutrons and protons can now exist. -

ASTR110G Astronomy Laboratory Exercises C the GEAS Project 2020

ASTR110G Astronomy Laboratory Exercises c The GEAS Project 2020 ASTR110G Laboratory Exercises Lab 1: Fundamentals of Measurement and Error Analysis ...... ....................... 1 Lab 2: Observing the Sky ............................... ............................. 35 Lab 3: Cratering and the Lunar Surface ................... ........................... 73 Lab 4: Cratering and the Martian Surface ................. ........................... 97 Lab 5: Parallax Measurements and Determining Distances ... ....................... 129 Lab 6: The Hertzsprung-Russell Diagram and Stellar Evolution ..................... 157 Lab 7: Hubble’s Law and the Cosmic Distance Scale ........... ..................... 185 Lab 8: Properties of Galaxies .......................... ............................. 213 Appendix I: Definitions for Keywords ..................... .......................... 249 Appendix II: Supplies ................................. .............................. 263 Lab 1 Fundamentals of Measurement and Error Analysis 1.1 Introduction This laboratory exercise will serve as an introduction to all of the laboratory exercises for this course. We will explore proper techniques for obtaining and analyzing data, and practice plotting and analyzing data. We will discuss a scientific methodology for conducting exper- iments in which we formulate a question, predict the behavior of the system based on likely solutions, acquire relevant data, and then compare our predictions with the observations. You will have a chance to plan a short experiment, -

A Detailed Study of Gas and Star Formation in a Highly Magnified Lyman Break Galaxy at Z= 3.07

Draft version October 30, 2018 A Preprint typeset using L TEX style emulateapj v. 11/12/01 A DETAILED STUDY OF GAS AND STAR FORMATION IN A HIGHLY MAGNIFIED LYMAN BREAK GALAXY AT Z =3.07 K.E.K. Coppin1, A.M. Swinbank1, R. Neri2, P. Cox2, Ian Smail1, R. S. Ellis3, J. E. Geach1, B. Siana4, H. Teplitz4, S. Dye5, J.-P. Kneib6, A.C. Edge1, J. Richard3 Draft version October 30, 2018 ABSTRACT We report the detection of CO(3–2) emission from a bright, gravitationally lensed Lyman Break Galaxy, LBGJ213512.73–010143 (the “Cosmic Eye”), at z =3.07 using the Plateau de Bure Interferom- eter. This is only the second detection of molecular gas emission from an LBG and yields an intrinsic 9 molecular gas mass of (2.4 ± 0.4) × 10 M⊙. The lens reconstruction of the UV morphology of the LBG indicates that it comprises two components separated by ∼ 2 kpc. The CO emission is unresolved, ′′ θ <∼ 3 , and appears to be centered on the intrinsically fainter (and also less highly magnified) of the 9 2 two UV components. The width of the CO line indicates a dynamical mass of (8 ± 2) × 10 csc i M⊙ within the central 2 kpc. Employing mid-infrared observations from Spitzer we infer a stellar mass of 9 −1 M∗ ∼ (6 ± 2)×10 M⊙ and a star-formation rate of ∼ 60 M⊙ yr , indicating that the molecular gas will be consumed in <∼ 40 Myr. The gas fractions, star-formation efficiencies and line widths suggests that LBG J213512 is a high-redshift, gas-rich analog of a local luminous infrared galaxy. -

RADICAL SOFTWARE 24 East 22 Street

r y~~~~" " "~~ " yqv ~i ~//~ ~ r r /~r . rl i' v'~~~ ~l"1~.~,',~~ ':'" a~vtsti" f iW yV~opt " "w ~iW The ELECTROMAGNETIC SPECTRUIVI I RAY VERY LOW _FREQUENCY_.. (VLF) LF MF HF VHF UHF SHF EHF INFRAREp VISIBLE ULTRAVIOLET X-RAY GAMMA-RAY COSM C- ~uGY.RY~ . a ~ a a P L f R R QV~SuI~YWIm.Yr-w am .Y-r.y Mn-w~lu~ ~k~ rUltrnonks~ ~~ n ~ ~u Yk,owwi IMnrW R+.y ~Y $1 .25 VIDEO CARTRIDGE/CASSETTE SYSTEMS- CONTENTS COMPARATIVE TABLE Techniques-excerpts from a transcript Paul Ryan ENVIRONMENT/EVENTS NUMBER 2 1970 Video Balloon Pedro Lujan Electronic Tune Up Andrea Brown CABLE Charles Bensinger Space Station What is Cable? Liam O'Gallagher Television Is Electromagnetic Spectrum Douglas Davis/ Channel Allocation Fred Pitts SelfProcessing FCC Report on Program Origination Paul Ryan Cable Rap COMMUNITY Cable Systems Chart Video in El Barrio and the Classroom Elliot S . Glass Alternatives for Alternate LASER Media-People's Video Theatre Handbook A Short History of the Laser Lloyd Cross Ken Marsh Project Report The Potential Impact of the Laser on the Allen Rucker Video Medium Lloyd Cross Richard Kletter Television as Town Meeting Frequency and Form Vic Gioscia Dorothy Todd Henaut Televisionaries vs. Televisigoths David Silver excerpts from Neuron Cluster Grope Don Benson excerpts from Technology Against Technology= Anti-Tech Takis CULTURAL DATA BANK Sparks Scott & Freude Bartlett People's Video Theatre EQUIPMENT Jackie Cassen Raindance Corp . Standards Eric Siegel Steve Christianson Eric Siegel X-Rays Don Ward Tom DeWitt TVX Tips for Using Portable Half-Inch Equipment Parry Teasdale Electric Eye Stan VanDerBeek Microphones Fobile Muck Truck Woody Vasulka What is Television? Videoforms _Phil Gietzen Videofreex, Inc . -

Spitzer's Perspective of Polycyclic Aromatic Hydrocarbons in Galaxies

REVIEW ARTICLE https://doi.org/10.1038/s41550-020-1051-1 Spitzer’s perspective of polycyclic aromatic hydrocarbons in galaxies Aigen Li Polycyclic aromatic hydrocarbon (PAH) molecules are abundant and widespread throughout the Universe, as revealed by their distinctive set of emission bands at 3.3, 6.2, 7.7, 8.6, 11.3 and 12.7 μm, which are characteristic of their vibrational modes. They are ubiquitously seen in a wide variety of astrophysical regions, ranging from planet-forming disks around young stars to the interstellar medium of the Milky Way and other galaxies out to high redshifts at z ≳ 4. PAHs profoundly influence the thermal budget and chemistry of the interstellar medium by dominating the photoelectric heating of the gas and controlling the ionization balance. Here I review the current state of knowledge of the astrophysics of PAHs, focusing on their observational characteristics obtained from the Spitzer Space Telescope and their diagnostic power for probing the local physical and chemi- cal conditions and processes. Special attention is paid to the spectral properties of PAHs and their variations revealed by the Infrared Spectrograph onboard Spitzer across a much broader range of extragalactic environments (for example, distant galax- ies, early-type galaxies, galactic halos, active galactic nuclei and low-metallicity galaxies) than was previously possible with the Infrared Space Observatory or any other telescope facilities. Also highlighted is the relation between the PAH abundance and the galaxy metallicity established for the first time by Spitzer. n the early 1970s, a new chapter in astrochemistry was opened by some of the longstanding unexplained interstellar phenomena (for Gillett et al.1 who, on the basis of ground observations, detected example, the 2,175 Å extinction bump9,16,19, the diffuse interstellar three prominent emission bands peaking at 8.6, 11.3 and 12.7 μm bands20, the blue and extended red photoluminescence emission21 I 22,23 in the 8–14 μm spectra of two planetary nebulae, NGC 7027 and and the ‘anomalous microwave emission’ ). -

The Fantastically Marvellous Universe

books & arts The fantastically marvellous universe Time in Powers After all, they grew up with Google Earth. timescales on which planets and galaxies of Ten: Natural A three-year-old can now use her fingers to would have long broken apart and faded Phenomena and zoom in and out on images of our Galaxy beyond the observable horizon and protons Their Timescales or cells with apps such as Cosmic Eye. would have decayed. The second part But I find Boeke’s black-and-white begins with the unimaginably short Planck illustrations rather charming (especially time (10−44 seconds) before making its way the first photograph of a girl with a cat, back to one second. Time in Powers of Ten proving that cats had taken over physics can then be read in any direction or well before invading the Internet) and one can randomly jump from chapter By Gerard ‘t Hooft and Stefan Vandoren; the explanations much more informative to chapter. translated by Saskia Eisberg-‘t Hooft and compelling than the brief notes The book is rich in examples from provided in the app. And the Powers of Ten nuclear and particle physics: half-lives of WORLD SCIENTIFIC: 2014. 232 PP. £16.00 short film is equally delightful with its different isotopes and subatomic particles. soundtrack reminding one of the original I would perhaps have liked more examples here is certainly no shortage of Star Trek series. from other areas, especially of ultrafast popular and scientific books Visualizing length scales is not that phenomena; but the authors promise a Ton time. -

Download Lesson

Earth Science Mysteries of Space Where would you search for life in space? Module 1 What does our solar system look like? Module 2 Why does our solar system look the way it does? Module 3 What Would it take to survive in space? Teams use what they know about the scale and Final nature of our solar system and galaxy to design Product: a mystery organism that can endure the forces and elements found on another moon or planet. Module Overview Module 1: Our Solar System Mysteries of Space Dear Educator, We are very excited to bring you this lesson from a three week, Educurious project-based learning unit, Mysteries of Space. If you are planning to use this lesson independently of the unit or in a remote learning setting, we have included suggested adaptions throughout the lesson in bold, colored font in the Teacher Guide section. Unit Driving Question Where would you search for life in space? Module Driving Question What does our solar system look like? Our Solar System Shaping our Solar Life in Space What does our solar System What would it take to system look like? Why does our solar survive in space? system look the way it does? Module 3 Module Module 2 Module Module 1 Module Module Overview In this first lesson, students use and analyze data to classify the planets and moons in our solar system by their defining characteristics in order to understand the diversity and nature of our solar system. Students are then introduced to the scale of the solar system, and the units scientists use to measure objects and distance in space.