“The Historical Roots of Shanghai's Modern Miracle”

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Interim Report Report Interim

CITICPacific interimreport CITIC Pacific Ltd 32/F CITIC Tower 2008 1 Tim Mei Avenue Central, Hong Kong Tel: +852 2820 2111 Fax: +852 2877 2771 www.citicpacific.com interim report 2008 Stock code: 0267 1 Financial Highlights 2 Major Businesses 3 Chairman’s Letter to Shareholders 5 Financial Review 19 Human Resources Financial Statements 20 Consolidated Profit and Loss Account 21 Consolidated Balance Sheet 22 Consolidated Cash Flow Statement 24 Consolidated Statement of Changes in Equity 25 Notes to the Accounts 30 Report on Review of Interim Financial Report Statutory Disclosure 31 Dividend and Closure of Register 31 Share Option Plan 34 Directors’ Interests in Securities 37 Substantial Shareholders 38 Share Capital 39 Continuing Disclosure Requirements under Rule 13.22 of the Listing Rules 40 Corporate Governance 41 Definition of Terms 42 Corporate Information financial highlights 2008 2007 in HK$ million six months ended 30 June Profit Attributable to Shareholders 4,377 4,968 Major Businesses’ Contribution Special Steel 1,839 1,123 Property 453 446 Infrastructure 689 844 Listed Subsidiaries CITIC 1616 83 2,020 Dah Chong Hong 151 187 Fair Value change of Investment Properties 490 416 Net Gain from Sale of Listed Shares 843 – Cash Contributed from all Businesses 5,295 4,316 as at as at 30 June 31 December Capital Employed 102,966 88,447 Shareholders’ Funds 61,060 59,793 Net Debt 31,211 20,609 Cash & Available Committed Loan Facilities 30,181 26,589 in HK$ six months ended 30 June Earnings per Share 1.99 2.25 Dividends per Share Regular 0.30 0.40 Special – 0.20 Staff 25,177 23,989 Please refer to Definition of Terms on page 41 CITIC Pacific Interim Report 2008 1 major businesses CITIC Pacific has unrivalled experience and expertise in operating businesses in China both on the mainland and in Hong Kong. -

OFFICIAL RECORD of PROCEEDINGS Thursday, 12 July

LEGISLATIVE COUNCIL ─ 12 July 2007 10569 OFFICIAL RECORD OF PROCEEDINGS Thursday, 12 July 2007 The Council continued to meet at Nine o'clock MEMBERS PRESENT: THE PRESIDENT THE HONOURABLE MRS RITA FAN HSU LAI-TAI, G.B.M., G.B.S., J.P. THE HONOURABLE JAMES TIEN PEI-CHUN, G.B.S., J.P. THE HONOURABLE ALBERT HO CHUN-YAN IR DR THE HONOURABLE RAYMOND HO CHUNG-TAI, S.B.S., S.B.ST.J., J.P. THE HONOURABLE LEE CHEUK-YAN THE HONOURABLE FRED LI WAH-MING, J.P. DR THE HONOURABLE LUI MING-WAH, S.B.S., J.P. THE HONOURABLE MARGARET NG THE HONOURABLE MRS SELINA CHOW LIANG SHUK-YEE, G.B.S., J.P. THE HONOURABLE JAMES TO KUN-SUN THE HONOURABLE CHEUNG MAN-KWONG THE HONOURABLE CHAN YUEN-HAN, S.B.S., J.P. THE HONOURABLE BERNARD CHAN, G.B.S., J.P. 10570 LEGISLATIVE COUNCIL ─ 12 July 2007 THE HONOURABLE CHAN KAM-LAM, S.B.S., J.P. THE HONOURABLE MRS SOPHIE LEUNG LAU YAU-FUN, G.B.S., J.P. THE HONOURABLE LEUNG YIU-CHUNG THE HONOURABLE SIN CHUNG-KAI, S.B.S., J.P. DR THE HONOURABLE PHILIP WONG YU-HONG, G.B.S. THE HONOURABLE WONG YUNG-KAN, S.B.S., J.P. THE HONOURABLE JASPER TSANG YOK-SING, G.B.S., J.P. THE HONOURABLE HOWARD YOUNG, S.B.S., J.P. DR THE HONOURABLE YEUNG SUM, J.P. THE HONOURABLE LAU CHIN-SHEK, J.P. THE HONOURABLE LAU KONG-WAH, J.P. THE HONOURABLE LAU WONG-FAT, G.B.M., G.B.S., J.P. -

China's NOTES from the EDITORS 4 Who's Hurting Who with National Culture

—Inspired by the Lei Feng* spirit of serving the people, primary school pupils of Harbin City often do public cleanups on their Sunday holidays despite severe winter temperature below zero 20°C. Photo by Men Suxian * Lei Feng was a squad leader of a Shenyang unit of the People's Liberation Army who died on August 15, 1962 while on duty. His practice of wholeheartedly serving the people in his ordinary post has become an example for all Chinese people, especially youfhs. Beijing««v!r VOL. 33, NO. 9 FEB. 26-MAR. 4, 1990 Carrying Forward the Cultural Heritage CONTENTS • In a January 10 speech. CPC Politburo member Li Ruihuan stressed the importance of promoting China's NOTES FROM THE EDITORS 4 Who's Hurting Who With national culture. Li said this will help strengthen the coun• Sanctions? try's sense of national identity, create the wherewithal to better resist foreign pressures, and reinforce national cohe• EVENTS/TRENDS 5 8 sion (p. 19). Hong Kong Basic Law Finalized Economic Zones Vital to China NPC to Meet in March Sanctions Will Get Nowhere Minister Stresses Inter-Ethnic Unity • Some Western politicians, in defiance of the reahties and Dalai's Threat Seen as Senseless the interests of both China and their own countries, are still Farmers Pin Hopes On Scientific demanding economic sanctions against China. They ignore Farming the fact that sanctions hurt their own interests as well as 194 AIDS Cases Discovered in China's (p. 4). China INTERNATIONAL Upholding the Five Principles of Socialism Will Save China Peaceful Coexistence 9 Mandela's Release: A Wise Step o This is the first instalment of a six-part series contributed Forward 13 by a Chinese student studying in the United States. -

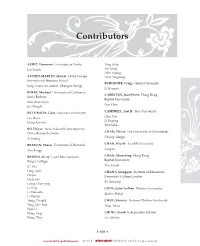

Contributors.Indd Page 569 10/20/15 8:21 AM F-479 /203/BER00069/Work/Indd/%20Backmatter

02_Contributors.indd Page 569 10/20/15 8:21 AM f-479 /203/BER00069/work/indd/%20Backmatter Contributors AUBIÉ, Hermann University of Turku Yang Jiang Liu Xiaobo Yao Ming Zhao Ziyang AUSTIN-MARTIN, Marcel China Europe Zhou Youguang International Business School BURGDOFF, Craig Capital University Jiang Zemin (co-author: Zhengxu Wang) Li Hongzhi BERRY, Michael University of California, CABESTAN, Jean-Pierre Hong Kong Santa Barbara Baptist University Hou Hsiao-hsien Lien Chan Jia Zhangke CAMPBELL, Joel R. Troy University BETTINSON, Gary Lancaster University Chen Yun Lee, Bruce Li Keqiang Wong Kar-wai Wen Jiabao BO Zhiyue New Zealand Contemporary CHAN, Felicia The University of Manchester China Research Centre Cheung, Maggie Xi Jinping BRESLIN, Shaun University of Warwick CHAN, Hiu M. Cardiff University Zhu Rongji Gong Li BROWN, Kerry Lau China Institute, CHAN, Shun-hing Hong Kong King’s College Baptist University Bo Yibo Zen, Joseph Fang Lizhi CHANG Xiangqun Institute of Education, Hu Jia University College London Hu Jintao Fei Xiaotong Leung Chun-ying Li Peng CHEN, Julie Yu-Wen Palacky University Li Xiannian Kadeer, Rebiya Li Xiaolin Tsang, Donald CHEN, Szu-wei National Taiwan University Tung Chee-hwa Teng, Teresa Wan Li Wang Yang CHING, Frank Independent Scholar Wang Zhen Lee, Martin • 569 • www.berkshirepublishing.com © 2015 Berkshire Publishing grouP, all rights reserved. 02_Contributors.indd Page 570 9/22/15 12:09 PM f-500 /203/BER00069/work/indd/%20Backmatter • Berkshire Dictionary of Chinese Biography • Volume 4 • COHEN, Jerome A. New -

Socioterritorial Fractures in China: the Unachievable “Harmonious Society”?

China Perspectives 2007/3 | 2007 Creating a Harmonious Society Socioterritorial Fractures in China: The Unachievable “Harmonious Society”? Guillaume Giroir Édition électronique URL : http://journals.openedition.org/chinaperspectives/2073 DOI : 10.4000/chinaperspectives.2073 ISSN : 1996-4617 Éditeur Centre d'étude français sur la Chine contemporaine Édition imprimée Date de publication : 15 septembre 2007 ISSN : 2070-3449 Référence électronique Guillaume Giroir, « Socioterritorial Fractures in China: The Unachievable “Harmonious Society”? », China Perspectives [En ligne], 2007/3 | 2007, mis en ligne le 01 septembre 2010, consulté le 28 octobre 2019. URL : http://journals.openedition.org/chinaperspectives/2073 ; DOI : 10.4000/ chinaperspectives.2073 © All rights reserved Special feature s e Socioterritorial Fractures v i a t c n i in China: The Unachievable e h p s c “Harmonious Society”? r e p GUILLAUME GIROIR This article offers an inventory of the social and territorial fractures in Hu Jintao’s China. It shows the unarguable but ambiguous emergence of a middle class, the successes and failures in the battle against poverty and the spectacular enrichment of a wealthy few. It asks whether the Confucian ideal of a “harmonious society,” which the authorities have been promoting since the early 2000s, is compatible with a market economy. With an eye to the future, it outlines two possible scenarios on how socioterritorial fractures in China may evolve. he need for a “more harmonious society” was raised 1978, Chinese society has effectively ceased to be founded for the first time in 2002 at the Sixteenth Congress on egalitarianism; spatial disparities are to be seen on the T of the Communist Party of China (CPC). -

The Collection and Digitization of the Genealogies in the National Library of China

Submitted on: June 24, 2013 The Collection and Digitization of the Genealogies in the National Library of China Xie Dongrong National Library of China, Beijing, China. Xiao Yu National Library of China, Beijing, China. Shi Jian National Library of China, Beijing, China. Copyright © 2013 by Xie Dongrong, Xiao Yu and Shi Jian. This work is made available under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution 3.0 Unported License: http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/3.0/ Abstract: The history of the genealogies collection of NLC has been reviewed and the current situation of the collection is introduced as well. The character and value of the genealogies in NLC is analyzed and the digitalization of the collections in different levels is emphasized including the various services to the readers basing on these digital products. 1) The genealogies have been catalogued in MARC format and the fundamental information of the collections is described. 2) The images of the original genealogies are acquired by scanning or photographing, which are provided to the readers with the cataloging data and the volumes information of the genealogies. 3) The genealogies have been indexed, the indexes to the titles and family members are focused on which described the information of the peoples and articles in the documents that can be used separately or accompanying with the images. 4) The images are transformed into the text format and the full text search can be achieved. 5) The people relations in the pedigrees in the genealogies are sorted out and the data of the family trees is acquired. The readers can search the database by people relation and specify the searching result. -

(Hrsg.) Strafrecht in Reaktion Auf Systemunrecht

Albin Eser / Ulrich Sieber / Jörg Arnold (Hrsg.) Strafrecht in Reaktion auf Systemunrecht Schriftenreihe des Max-Planck-Instituts für ausländisches und internationales Strafrecht Strafrechtliche Forschungsberichte Herausgegeben von Ulrich Sieber in Fortführung der Reihe „Beiträge und Materialien aus dem Max-Planck-Institut für ausländisches und internationales Strafrecht Freiburg“ begründet von Albin Eser Band S 82.9 Strafrecht in Reaktion auf Systemunrecht Vergleichende Einblicke in Transitionsprozesse herausgegeben von Albin Eser • Ulrich Sieber • Jörg Arnold Band 9 China von Thomas Richter sdfghjk Duncker & Humblot • Berlin Bibliografische Information der Deutschen Bibliothek Die Deutsche Bibliothek verzeichnet diese Publikation in der Deutschen Nationalbibliografie; detaillierte bibliografische Daten sind im Internet über <http://dnb.ddb.de> abrufbar. DOI https://doi.org/10.30709/978-3-86113-876-X Redaktion: Petra Lehser Alle Rechte vorbehalten © 2006 Max-Planck-Gesellschaft zur Förderung der Wissenschaften e.V. c/o Max-Planck-Institut für ausländisches und internationales Strafrecht Günterstalstraße 73, 79100 Freiburg i.Br. http://www.mpicc.de Vertrieb in Gemeinschaft mit Duncker & Humblot GmbH, Berlin http://WWw.duncker-humblot.de Umschlagbild: Thomas Gade, © www.medienarchiv.com Druck: Stückle Druck und Verlag, Stückle-Straße 1, 77955 Ettenheim Printed in Germany ISSN 1860-0093 ISBN 3-86113-876-X (Max-Planck-Institut) ISBN 3-428-12129-5 (Duncker & Humblot) Gedruckt auf alterungsbeständigem (säurefreiem) Papier entsprechend ISO 9706 # Vorwort der Herausgeber Mit dem neunten Band der Reihe „Strafrecht in Reaktion auf Systemunrecht – Vergleichende Einblicke in Transitionsprozesse“ wird zur Volksrepublik China ein weiterer Landesbericht vorgelegt. Während die bisher erschienenen Bände solche Länder in den Blick nahmen, die hinsichtlich der untersuchten Transitionen einem „klassischen“ Systemwechsel von der Diktatur zur Demokratie entsprachen, ist die Einordung der Volksrepublik China schwieriger. -

China Data Supplement January 2007

China Data Supplement January 2007 J People’s Republic of China J Hong Kong SAR J Macau SAR J Taiwan ISSN 0943-7533 China aktuell Data Supplement – PRC, Hong Kong SAR, Macau SAR, Taiwan 1 Contents The Main National Leadership of the PRC 2 LIU Jen-Kai The Main Provincial Leadership of the PRC 30 LIU Jen-Kai Data on Changes in PRC Main Leadership 37 LIU Jen-Kai PRC Agreements with Foreign Countries 55 LIU Jen-Kai PRC Laws and Regulations 57 LIU Jen-Kai Hong Kong SAR 62 Political, Social and Economic Data LIU Jen-Kai Macau SAR 69 Political, Social and Economic Data LIU Jen-Kai Taiwan 73 Political, Social and Economic Data LIU Jen-Kai ISSN 0943-7533 All information given here is derived from generally accessible sources. Publisher/Distributor: GIGA Institute of Asian Studies Rothenbaumchaussee 32 20148 Hamburg Germany Phone: +49 (0 40) 42 88 74-0 Fax: +49 (040) 4107945 2 January 2007 The Main National Leadership of the PRC LIU Jen-Kai Abbreviations and Explanatory Notes CCP CC Chinese Communist Party Central Committee CCa Central Committee, alternate member CCm Central Committee, member CCSm Central Committee Secretariat, member PBa Politburo, alternate member PBm Politburo, member BoD Board of Directors Cdr. Commander CEO Chief Executive Officer Chp. Chairperson COO Chief Operating Officer CPPCC Chinese People’s Political Consultative Conference CYL Communist Youth League Dep.Cdr. Deputy Commander Dep. P.C. Deputy Political Commissar Dir. Director exec. executive f female Gen.Man. General Manager Hon.Chp. Honorary Chairperson Hon.V.-Chp. Honorary Vice-Chairperson MPC Municipal People’s Congress NPC National People’s Congress PCC Political Consultative Conference PLA People’s Liberation Army Pol.Com. -

Him Mark Lai Container List.Docx

Finding Aid to the Him Mark Lai research files, additions, 1834-2009 (bulk 1970-2008) Collection number: AAS ARC 2010/1 Ethnic Studies Library University of California, Berkeley Berkeley, California Funding for processing this collection was provided by Mrs. Laura Lai. Date Completed: June 2014 Finding Aid Written By: Dongyi (Helen) Qi, Haochen (Daniel) Shan, Shuyu (Clarissa) Lu, and Janice Otani. © 2014 The Regents of the University of California. All rights reserved. COLLECTION SUMMARY Collection Title: Him Mark Lai research files, additions, 1834-2009 (bulk 1970-2008) Collection Number: AAS ARC 2010/1 Creator: Lai, H. Mark Extent: 95 Cartons, 33 Boxes, 7 Oversize Folders; (131.22 linear feet) Repository: Ethnic Studies Library University of California, Berkeley Berkeley, California, 94720-2360 Phone: (510) 643-1234 Fax: (510) 643-8433 Email: [email protected] Abstract: The research files are a continuation of (AAS ARC 2000/80) Him Mark Lai’s collected sources, along with his own writings and professional activity materials that relate to the history, communities, and organizations of Chinese Americans and Chinese overseas. The collection is divided into four series: Research Files, including general subjects, people, and organizations; Writings, including books, articles and indexes; Professional activities, primarily including teaching lectures, Chinese Community Hour program tapes, In Search of Roots program materials, consultation projects, interviews with Chinese Americans, conference and community events; Personal, including memorial tributes; correspondence, photographs, and slides of family and friends. The collection consists of manuscripts, papers, drafts, indexes, correspondence, organization records, reports, legal documents, yearbooks, announcements, articles, newspaper samples, newspaper clippings, publications, photographs, slides, maps, and audio tapes. -

China Inc's Debacle in the Outback

CITIC FIRST PRINCELING: Larry Yung, son of legendary “red capitalist” Rong Yiren, was once rated the richest tycoon in China. REUTERS/BOBBY YIP A “princeling” tycoon led a multibillion-dollar China Inc’s iron-mining project in Australia. As debacle in losses mount, Hong Kong prosecutors are weighing the Outback charges, Reuters has learned BY DAVID LAGUE HONG KONG, AUGUST 31, 2012 arry Yung Chi-kin is a loyal scion of the Chinese Communist upper L crust. His late father, Rong Yiren, was the legendary “Red Capitalist,” one of the few industrialists to stay behind in the mainland after the revolution of 1949. Yung himself went on to found the con- glomerate CITIC Pacific and become one of China’s richest men. So, when duty called, Larry Yung answered. In 2006, foreign mining giants were jacking up prices of the iron ore needed by China’s voracious steel industry. At the urg- ing of Beijing, Yung and CITIC Pacific ne- gotiated the rights to exploit a vast deposit of low-grade ore in the red-rock landscape of Australia’s remote northwest Pilbara region. The multibillion-dollar deal seemed SPECIAL REPORT 1 CITIC CHINA INC’S DEBACLE IN THE OUTBACK Citic Down Under Citic Pacific bet wrongly on the Aussie dollar in 2008. Now iron ore prices are turning against it. AUSTRALIAN DOLLAR INDEX IRON ORE SPOT PRICE June-July 2008 80 Citic hedges against rising $150 per metric tonne Australian dollar 70 100 Iron-ore prices 60 Sept. 7, 2008 50 are expected to Yung learns of exposure continue sliding to falling currency as China’s economy shows signs of slowing 50 0 2007 '08 '09 '10 '11 '12 '09 '10 '11 '12 Source: Thomson Reuters Datastream to be a coup for China’s resource-hungry further $2 billion in losses. -

Introduction

Notes Introduction 1 See, for example, ‘Taking on the World’, Business China, vol. 26, 20 Novem- ber 2000; ‘Bank of China Thinks Global’, Far Eastern Economic Review, 7 December 2000; ‘China Business Goes Global’, Far Eastern Economic Review, 28 March 2002; and ‘Chinese Insurer Targets Global Markets’, Wall Street Journal, 18 January 2000. 2 One of the most recent is Kevin Cai’s ‘Outward Foreign Direct Investment: A Novel Dimension of China’s Integration into the Regional and Global Economy’, in China Quarterly (Cai 1999). Otherwise, there are two technical papers published by the Organisation for Economic Cooperation and Devel- opment (OECD), one by Yun-Wing Sung (1991) on Chinese Outward Invest- ment in Hong Kong: Trends, Prospects and Policy Implications, and the other by David Wall (1996) on Outflows of Capital from China. Other essays have made their way into Transnational Corporations, including James Zhan’s ‘Transna- tionalisation and Outward Investment: The Case of Chinese Firms’ (1995). There are also some book chapters, most notably by Tseng Choo-Sin (1994, 1996), and Haiyan Zhang and Daniel van den Bulcke (1994, 1996). We may add to the list three working papers published by the Strathclyde Interna- tional Business Unit. Occasional discussions on the international business conducted by individual Chinese firms also appear in such studies as Nolan (1996, 1998) and Steinfeld (1998). The primary focus of these studies is not, however, the transnationalisation of the firm concerned. 3 Throughout this study, we use ‘firms’, ‘enterprises’ and ‘companies’ in the Chinese context interchangeably and advisably to avoid definitional prob- lems associated with the transitional nature of China’s industrial organisa- tion. -

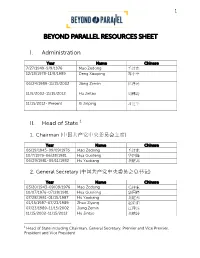

Beyond Parallel Resources Sheet

1 BEYOND PARALLEL RESOURCES SHEET I. Administration Year Name Chinese 7/27/1949-9/9/1976 Mao Zedong 毛泽东 12/18/1978-11/8/1989 Deng Xiaoping 邓小平 06/24/1989-11/15/2002 Jiang Zemin 江泽民 11/5/2002-11/15/2012 Hu Jintao 胡锦涛 11/15/2012- Present Xi Jinping 习近平 II. Head of State 1 1. Chairman (中国共产党中央委员会主席) Year Name Chinese 06/19/1945-09/09/1976 Mao Zedong 毛泽东 10/7/1976-06/28/1981 Hua Guofeng 华国锋 06/29/1981-09/11/1982 Hu Yaobang 胡耀邦 2. General Secretary (中国共产党中央委员会总书记) Year Name Chinese 03/20/1943-09/09/1976 Mao Zedong 毛泽东 10/07/1976-07/28/1981 Hua Guofeng 华国锋 07/28/1981-01/15/1987 Hu Yaobang 胡耀邦 01/15/1987-07/23/1989 Zhao Ziyang 赵紫阳 07/23/1989-11/15/2002 Jiang Zemin 江泽民 11/15/2002-11/15/2012 Hu Jintao 胡锦涛 1 Head of State including Chairman, General Secretary, Premier and Vice Premier, President and Vice President 2 11/15/2012-Present Xi Jinping 习近平 3. Premier (中华人民共和国国务院总理) Year Name Chinese 10/1949-01/1976 Zhou Enlai 周恩来 2/2/1976-09/10/1980 Hua Guofeng 华国锋 09/10/1980-11/24/1987 Zhao Ziyang 赵紫阳 11/24/1987-03/17/1998 Li Peng 李鹏 03/17/1998-03/16/2003 Zhu Rongji 朱镕基 03/16/2003-03/15/2013 Wen Jiabao 温家宝 03/15/2013-Present Li Keqiang 李克强 4. Vice Premier (中华人民共和国国务院副总理) Year Name Chinese 09/15/1954-12/21/1964 Chen Yun 陈云 12/21/1964-09/13/1971 Lin Biao 林彪 09/13/1971-09/10/1980 Deng Xiaoping 邓小平 09/10/1980-03/25/1988 Wan Li 万里 03/25/1988-3/05/1993 Yao Yilin 姚依林 3/25/1993-03/17/1998 Zhu Rongji 朱镕基 03/17/1998-03/06/2003 Li Lanqing 李岚清 03/06/2003-06/02/2007 Huang Ju 黄菊 06/02/2007-03/16/2008 Wu Yi 吴仪 03/16/2008-03/16/2013 Li Keqiang 李克强 03/16/2013-Present Zhang Gaoli 张高丽 5.