Download Transcript

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Stories of Minjung Theology

International Voices in Biblical Studies STORIES OF MINJUNG THEOLOGY STORIES This translation of Asian theologian Ahn Byung-Mu’s autobiography combines his personal story with the history of the Korean nation in light of the dramatic social, political, and cultural upheavals of the STORIES OF 1970s. The book records the history of minjung (the people’s) theology that emerged in Asia and Ahn’s involvement in it. Conversations MINJUNG THEOLOGY between Ahn and his students reveal his interpretations of major Christian doctrines such as God, sin, Jesus, and the Holy Spirit from The Theological Journey of Ahn Byung‑Mu the minjung perspective. The volume also contains an introductory essay that situates Ahn’s work in its context and discusses the place in His Own Words and purpose of minjung hermeneutics in a vastly different Korea. (1922–1996) was professor at Hanshin University, South Korea, and one of the pioneers of minjung theology. He was imprisonedAHN BYUNG-MU twice for his political views by the Korean military government. He published more than twenty books and contributed more than a thousand articles and essays in Korean. His extended work in English is Jesus of Galilee (2004). In/Park Electronic open access edition (ISBN 978-0-88414-410-6) available at http://ivbs.sbl-site.org/home.aspx Translated and edited by Hanna In and Wongi Park STORIES OF MINJUNG THEOLOGY INTERNATIONAL VOICES IN BIBLICAL STUDIES Jione Havea, General Editor Editorial Board: Jin Young Choi Musa W. Dube David Joy Aliou C. Niang Nasili Vaka’uta Gerald O. West Number 11 STORIES OF MINJUNG THEOLOGY The Theological Journey of Ahn Byung-Mu in His Own Words Translated by Hanna In. -

Brand New Cd & Dvd Releases 2006 6,400 Titles

BRAND NEW CD & DVD RELEASES 2006 6,400 TITLES COB RECORDS, PORTHMADOG, GWYNEDD,WALES, U.K. LL49 9NA Tel. 01766 512170: Fax. 01766 513185: www. cobrecords.com // e-mail [email protected] CDs, DVDs Supplied World-Wide At Discount Prices – Exports Tax Free SYMBOLS USED - IMP = Imports. r/m = remastered. + = extra tracks. D/Dble = Double CD. *** = previously listed at a higher price, now reduced Please read this listing in conjunction with our “ CDs AT SPECIAL PRICES” feature as some of the more mainstream titles may be available at cheaper prices in that listing. Please note that all items listed on this 2006 6,400 titles listing are all of U.K. manufacture (apart from Imports which are denoted IM or IMP). Titles listed on our list of SPECIALS are a mix of U.K. and E.C. manufactured product. We will supply you with whichever item for the price/country of manufacture you choose to order. ************************************************************************************************************* (We Thank You For Using Stock Numbers Quoted On Left) 337 AFTER HOURS/G.DULLI ballads for little hyenas X5 11.60 239 ANATA conductor’s departure B5 12.00 327 AFTER THE FIRE a t f 2 B4 11.50 232 ANATHEMA a fine day to exit B4 11.50 ST Price Price 304 AG get dirty radio B5 12.00 272 ANDERSON, IAN collection Double X1 13.70 NO Code £. 215 AGAINST ALL AUTHOR restoration of chaos B5 12.00 347 ANDERSON, JON animatioin X2 12.80 92 ? & THE MYSTERIANS best of P8 8.30 305 AGALAH you already know B5 12.00 274 ANDERSON, JON tour of the universe DVD B7 13.00 -

A Monster Is Coming! Free

FREE A MONSTER IS COMING! PDF David L Harrison,Hans Wilhelm | 32 pages | 22 Feb 2011 | Random House USA Inc | 9780375866777 | English | New York, United States Is Monster Hunter Rise Coming to PC? Answered The track was released on 5 June in the UK and subsequently reached No. It is The Automatic's highest charting single to date in the United Kingdom. The track's music was composed by James Frost and Robin Hawkinswith the original incarnation featuring a different chorus, both musically and lyrically. However the band decided first to change the music before deciding to rewrite the chorus's lyrics. The chorus was planned to have a fairytale- esque theme to it, with keyboardist and vocalist A Monster Is Coming! Pennie penning the idea which would become the track's famous lyric "What's that coming over the hill? Is it a monster? Originally however, the lyric was used just to fill the chorus until a more suitable A Monster Is Coming! was A Monster Is Coming!, but over time the lyric stuck and so was eventually used when the band recorded a demo of it in Many of the lyrics used in "Monster" are metaphors for drug and drink intoxication; "brain fried tonight through misuse" and "without these pills you're let loose"with the chorus 'monster' lyric A Monster Is Coming! a metaphor for the monster that comes out when people are intoxicated. The original demo of "Monster" featured more prominent synthesizers, with some different vocals, including more gang vocals during the chorus and distorted backing vocals during the verses and bridge. -

Locked Out, Locked In: Young People, Adulthood and Desistance from Crime Briege Nugent Brown Phd the University of Edinburgh 20

Locked out, locked in: Young people, adulthood and desistance from crime Briege Nugent Brown PhD The University of Edinburgh 2017 DECLARATION OF ORIGINAL WORK I hereby confirm that I have composed this thesis and that this thesis is all my own work. I also declare that this work has not been submitted for any other degree or professional qualification. Signed __________________________on _________________________. ii iii ABSTRACT This thesis presents findings from a longitudinal study of young people living in poverty providing a unique insight into their lives. The research set out to explore three themes, namely how young people end contact successfully (or not) from support, their experiences of the ‘transition to adulthood’ and also what triggered, helped and hindered those who were trying to desist from offending. It was revealed that a small number never left Includem’s Transitional Support, a unique service set up in Scotland providing emotional and practical help for vulnerable young people in this age group. For those who did leave, many had limited to no other support in their lives and were reluctant to ask for help again even when they were in real need. They were all acutely aware of their precarious situation. ‘Adulthood’ denoted certainty for them and was not viewed as a feasible destination. Members of the group dealt with this differently. Almost all retained hope of achieving their goals and in doing so suffered a form of ‘cruel optimism’, conversely, a smaller number scaled back on their aspirations, sometimes even to the extent of focusing on their immediate day to day survival. -

NATIONAL LIFE STORIES ARTISTS' LIVES Kyffin Williams Interviewed

NATIONAL LIFE STORIES ARTISTS’ LIVES Kyffin Williams Interviewed by Cathy Courtney C466/24 This transcript is copyright of the British Library Board. Please refer to the Oral History curators at the British Library prior to any publication or broadcast from this document. Oral History The British Library 96 Euston Road London NW1 2DB 020 7412 7404 [email protected] This transcript is accessible via the British Library’s Archival Sound Recordings website. Visit http://sounds.bl.uk for further information about the interview. © The British Library Board http://sounds.bl.uk IMPORTANT Access to this interview and transcript is for private research only. Please refer to the Oral History curators at the British Library prior to any publication or broadcast from this document. Oral History The British Library 96 Euston Road London NW1 2DB 020 7412 7404 [email protected] Every effort is made to ensure the accuracy of this transcript, however no transcript is an exact translation of the spoken word, and this document is intended to be a guide to the original recording, not replace it. Should you find any errors please inform the Oral History curators ( [email protected] ) © The British Library Board http://sounds.bl.uk The British Library National Life Stories Interview Summary Sheet Title Page Ref no: C466/24 Digitised from cassette originals Collection title: Artists’ Lives Interviewee’s surname: Williams Title: Interviewee’s forename: Kyffin Sex: Male Occupation: Date and place of birth: 9th May 1918 Mother’s occupation: Father’s occupation: Dates of recording: 21 st – 22 nd March 1995 Location of interview: Interviewee’s home, Wales Name of interviewer: Cathy Courtney Type of recorder: Marantz CP430 Recording format: D60 Cassette F numbers of playback cassettes: F4540 - F4546 (7 cassettes) Total no. -

5000 New Students Descend on City for Week of Madness

Exclusive for Freshers’ Week: The Hoosiers and The Automatic play the Union For the full night time schedule, turn to Pulp on Page 9 ISSUE 1173 SEPTEMBER 2008 www.thecouriernewcastle.com FREE INSIDE Competitions Win tickets to see the Mighty Boosh and The Streets live! Page 20 Welfare All you need to know about staying fi t and healthy during the week Freshers’ Week 2008 Page 6 5000 new students descend on city for week of madness WELCOME TO Newcastle - a city famous galleries, this Freshers’ Week is about more remember to get your money’s worth! for many things that you will soon grow to than just partying – it’s about having new Finally, there is the 2008 Freshers’ Handbook love. experiences with new friends and getting to that will be handed to you as part of your But before you have a chance to meet the know the city that is now your home. welcome pack. Not only will it provide locals, sample the ‘Broon Ale’ or witness the Alongside all of the fun, there are huge you with something to remember Freshers’ fanatical following of the Toon Army, there measures in place to make sure your Week by, it also contains tons of information is another experience to enjoy that people all Freshers’ Week is safe as well as enjoyable. about the city and the area that can help you Activities across the country associate with your new Inside this special commemorative edition of get a head start on getting the most out of home city – Freshers’ Week! The Courier are details of all the tents, crews Newcastle and your student’s union. -

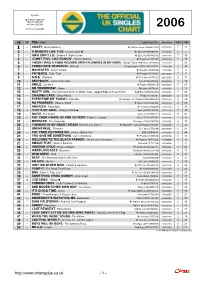

Chartsplus Year-End 2006

Symbols: p Platinum (600,000) ä Gold (400,000) è Silver (200,000) 2006 ² Former FutureHIT 06 05 Title - Artist Label (Cat. No.) Entry Date High Wks 9 1 -- CRAZY - Gnarls Barkley ² Warner Bros (WEA401CD) 08/04/2006 1 11 2 2 -- A MOMENT LIKE THIS - Leona Lewis ä ² Syco (88697050872) 30/12/2006 1 2 5 3 -- HIPS DON'T LIE - Shakira ft. Wyclef Jean ² Epic (82876842702) 17/06/2006 1 30 4 4 -- I DON'T FEEL LIKE DANCIN' - Scissor Sisters ² Polydor (1707529) 09/09/2006 1 18 5 -- I WISH I WAS A PUNK ROCKER (WITH FLOWERS IN MY HAIR) - Sandi Thom è² RCA (82876843422)27/05/2006 1 33 6 -- FROM PARIS TO BERLIN - Infernal Europa/Apollo (APOLLO102CDX) 22/04/2006 2 38 3 7 -- MANEATER - Nelly Furtado ² Polydor (9859585) 10/06/2006 1 9 4 8 -- PATIENCE - Take That ² Polydor (1714832) 25/11/2006 1 7 9 -- S.O.S. - Rihanna ² Def Jam (9877821) 22/04/2006 2 13 10 -- SEXYBACK - Justin Timberlake Jive (82876870882) 02/09/2006 1 19 2 11 -- SMILE - Lily Allen ² Regal (REGS135) 08/07/2006 1 27 12 -- NO TOMORROW - Orson Mercury (9876828) 11/03/2006 1 17 2 13 -- NASTY GIRL - The Notorious B.I.G. ft. Diddy, Nelly, Jagged Edge & Avery Storm Bad Boy (AT0229CDX) 28/01/2006 1 50 14 -- CHASING CARS - Snow Patrol Fiction (1704397) 29/07/2006 6 17 15 -- EVERYTIME WE TOUCH - Cascada All Around The World (CDGLOBE537) 05/08/2006 2 20 16 -- NO PROMISES - Shayne Ward ² Syco (82876825902) 22/04/2006 2 25 17 -- AMERICA - Razorlight ² Vertigo (1705368) 07/10/2006 1 14 4 18 2 THAT'S MY GOAL - Shayne Ward p Syco (82876779272) 31/12/2005 1 38 19 -- NAIVE - The Kooks Virgin (VSCDX1911) 01/04/2006 5 41 20 -- PUT YOUR HANDS UP FOR DETROIT - Fedde Le Grand Data (DATA140CDS) 28/10/2006 1 11 21 -- MONSTER - The Automatic B-Unique (BUN106CDX) 10/06/2006 4 10 2 22 -- THUNDER IN MY HEART AGAIN - Meck ft. -

The University of Southampton's Finest

The University of Southampton’s Finest Entertainment Publication Issue 8 29th ``April 2010 EDITORIAL WHAT’S GOING ON IN THIS ISSUE OF THE EDGE INSIDE.. Records - MGMT - Gorillaz - Two Door Cinema Club + More! Live - Tinie Tempah - You Me At Six + More! Film - Kick-Ass - The Blind Side + More! Tinie Tempah, Big Sound Features - Small Festival Feature - Red Bull Academy + More! THE EDGE PLAYLIST Games What’s Been Playing On The Edge Radio Show.. - Final Fantasy XIII Edge Radio Playlist (Surge) The Edge Team.. - Saturday 1pm - 2pm Editors - Tom Shepherd & Emmeline Curtis 1. Chiddy Bang - Truth Features Editor - Dan Morgan Records Editor - Kate Golding 2. Futures - Boy Who Cried Wolf Live Editor - Hayley Taulbut Film Editor - Stephen O’Shea 3. Gaslight Anthem - American Slang Games Editor - Joe Dart Editor-In-Chief - Jamie Ings 4. Ellie Goulding - Guns And Horses Sub-editors - James Miller 5. B.O.B feat. Hayley Williams - Airplanes 6. Save Your Breath - Stay Young 7. LCD Soundsystem - Drunk Girls 8. The Drums - Best Friend We are constantly on the look out for new writers that want to get Want To Get Involved? involved with The Edge. For more info email; [email protected] EDITORIAL ENTERTAINMENT WHAT’S GOING ON IN THIS ISSUE OF THE EDGE INSIDE.. Records - MGMT - Gorillaz - Two Door Cinema Club + More! Live - Tinie Tempah - You Me At Six + More! Film - Kick-Ass - The Blind Side + More! Tinie Tempah, Big Sound Features - Small Festival Feature - Red Bull Academy SuperGroups + More! THE EDGE PLAYLIST Like fashion, music has a knack for rein- backstage at a festival for fi ve minutes, and soon to release his all-star solo debut album, try which instated ‘Poutine’ (the rather gen- venting itself; or, depending on how you view he’ll probably form a new band and have an with guest spots from hard rock titans Fergie ius combination of chips, gravy and cheese What’s Been Playing On The Edge Radio Show. -

Cruise Planners

Holly Richardson [email protected] www.journeysofdreams.com 480-447-9977 HAVANA DESTINATION GUIDE OVERVIEW Introduction Havana is one of the world's most beguiling cities, one seemingly caught in colonial and 1950s time-warps. Old Havana, or Habana Vieja, is an amalgam of historic structures, cobbled plazas, castles, cathedrals and classical mansions that date back centuries from the height of Spanish international power. In fact, Havana's core is unrivaled in the Americas for its legacy of historic buildings, although many buildings are now in various states of dereliction; others have been renovated and serve as museums, hotels and restaurants. Beyond the old city core in Havana, the mid-20th-century enclave of Vedado teems with hotels and nightclubs that still maintain their 1950s atmosphere. They are set alongside gracious, century-old mansions of the long-departed well-to-do of Havana. Plaza de la Revolucion hosts Cuba's government buildings. Farther afield, visitors to Havana will find the Museo Hemingway and the glorious beaches of Playas del Este. Although Havana's physical attractions are reason enough to visit, travelers often go to Havana to experience the unique, almost surreal, amalgam of socialism and sensuality unique to Cuba. Five decades of communism have not been kind to the city of Havana, much of which is dilapidated. At times, the lives of Havana's inhabitants can be truly depressing. But the graciousness and joie de vivre of the Havanans shine through—especially their vivacious love of music and dance, which adds to the city's enigmatic travel appeal. The city is now in the midst of a reawakening thanks to President Raul Castro's economic reforms and the presence of more and more U.S. -

Still Life and Death Metal: Painting the Battle Jacket

Title Still Life and Death Metal: Painting the Battle Jacket Type The sis URL https://ualresearchonline.arts.ac.uk/id/eprint/12036/ Dat e 2 0 1 7 Citation Cardwell, Thomas (2017) Still Life and Death Metal: Painting the Battle Jacket. PhD thesis, University of the Arts London. Cr e a to rs Cardwell, Thomas Usage Guidelines Please refer to usage guidelines at http://ualresearchonline.arts.ac.uk/policies.html or alternatively contact [email protected] . License: Creative Commons Attribution Non-commercial No Derivatives Unless otherwise stated, copyright owned by the author Still Life and Death Metal: Painting the Battle Jacket By Thomas Robert Cardwell Thesis submitted in partial fulfilment of the requirements for the Degree of Doctor of Philosophy (PhD) Supervision Team: Mark Fairnington (Director of Studies) David Cross / James Faure Walker University of the Arts London CCW January 2017 Tom Cardwell, CCW Still Life and Death Metal: Painting the Battle Jacket Abstract This thesis aims to conduct a study of battle jackets using painting as a recording and analytical tool. A battle jacket is a customised garment worn in heavy metal subcultures that features decorative patches, band insignia, studs and other embellishments Battle jackets are significant in the expression of subcultural identity for those that wear them, and constitute a global phenomenon dating back at least to the 1970s. The art practice juxtaposes and re-contextualises cultural artefacts in order to explore the narratives and traditions that they are a part of. As such, the work is situated within the genre of contemporary still life and appropriative painting. -

SPEW Decides Not to Call for a Labour Party Vote ... and Not to Tell Its

A paper of Marxist polemic and Marxist unity SPEW decides not to call for a n Letters and debate n Lessons of ISO Labour Party vote ... and not to n Iran and war threats tell its readers anything about it n Cuba and Trotsky No 1252 May 23 2019 Towards a Communist Party of the European Union £1/€1.10 IF BORIS JOHNSON BECOMES TORY LEADER A GENERAL ELECTION WILL SOON FOLLOW. IF HE WINS THAT ELECTION BREXIT AND A JOINED-AT-THE-HIP ALLIANCE WITH DONALD TRUMP IS ON THE CARDS 2 weekly weekly 3 May 23 2019 worker worker May 23 2019 LETTERS put him on the street. Let’s look at this Letters may have been of the evidence. and occasionally loutish. With that in away at internal scabs. As SWP shortened because of Perhaps the most shocking and my mind, it was necessary, even for oppositionists said at the time, it is sentence: “The steering committee space. Some names quite chilling aspect of ‘Sex is not the SWP, to have people who had the perfectly possible to have criticism and proposed to expel Peter Gregson over may have been changed psyche’ is MacLean’s solution to her ability to sweep up from time to time. activity. You can walk and chew gum. his refusal to remove a link from his transgender ‘problem’: the creation of (Being in the SWP ‘diplomatic corps’ Exactly why Birchall still wants to personal website to someone who was “third gender/third space”. This “third wasn’t necessarily a comfortable parade the discredited cultural mores recommending an article posted on Shocking gender” is not a recognition of some position. -

Racism in Rural Areas

Racism in Rural Areas Final Report Study for the European Monitoring Centre on Racism and Xenophobia (EUMC) 30th November 2002 Contract No.: 3203 Berliner Institut für Vergleichende Sozialforschung Mitglied im Europäischen Migrationszentrum (in co-operation with EuroFor) Schliemannstraße 23 10437 Berlin Tel.: +49 40 44 65 10 65 Fax: + 49 30 444 10 85 email: [email protected] Authors: Dr. Jochen Blaschke and Guillermo Ruiz Torres DISCLAIMER: The opinions expressed by the author(s) do not reflect the opinion or position of the EUMC. The EUMC accepts no liability whatsoever with regard to the information, opinions or statements contained in this document. The content of this study does not bind the EUMC. No mention of any authority, organisation, company or individual shall imply any approval as to their standing and capability on the part of the EUMC. Contents Part I: Theoretical Introduction .............................................................................. 7 1. Preface....................................................................................................................... 8 3. Rural and Provincial Society .............................................................................. 18 4. City and Countryside as European Problems ................................................. 20 5. Migration into Rural Areas................................................................................. 23 6. Anti-Racism and Resistance ............................................................................... 25 7.