The Digital Divide in Brooklyn's Public High Schools

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

College Board's AP® Computer Science Female Diversity Award

College Board’s AP® Computer Science Female Diversity Award College Board’s AP Computer Science Female Diversity Award recognizes schools that are closing the gender gap and engaging more female students in computer science coursework in AP Computer Science Principles (AP CSP) and AP Computer Science A (AP CSA). Specifically, College Board is honoring schools who reached 50% or higher female representation in either of the two AP computer science courses in 2018, or whose percentage of the female examinees met or exceeded that of the school's female population in 2018. Out of more than 18,000 secondary schools worldwide that offer AP courses, only 685 have achieved this important result. College Board's AP Computer Science Female Diversity Award Award in 2018 School State AP CSA Academy for Software Engineering NY AP CSA Academy of Innovative Technology High School NY AP CSA Academy of Notre Dame MA AP CSA Academy of the Holy Angels NJ AP CSA Ann Richards School for Young Women Leaders TX AP CSA Apple Valley High School CA AP CSA Archbishop Edward A. McCarthy High School FL AP CSA Ardsley High School NY AP CSA Arlington Heights High School TX AP CSA Bais Yaakov of Passaic High School NJ AP CSA Bais Yaakov School for Girls MD AP CSA Benjamin N. Cardozo High School NY AP CSA Bishop Guertin High School NH AP CSA Brooklyn Amity School NY AP CSA Bryn Mawr School MD AP CSA Calvin Christian High School CA AP CSA Campbell Hall CA AP CSA Chapin School NY AP CSA Convent of Sacred Heart High School CA AP CSA Convent of the Sacred Heart NY AP CSA Cuthbertson High NC AP CSA Dana Hall School MA AP CSA Daniel Hand High School CT AP CSA Darlington Middle Upper School GA AP CSA Digital Harbor High School 416 MD AP CSA Divine Savior-Holy Angels High School WI AP CSA Dubiski Career High School TX AP CSA DuVal High School MD AP CSA Eastwood Academy TX AP CSA Edsel Ford High School MI AP CSA El Camino High School CA AP CSA F. -

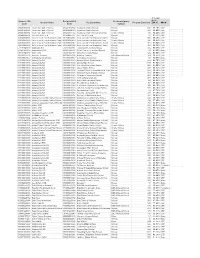

CEP May 1 Notification for USDA

40% and Sponsor LEA Recipient LEA Recipient Agency above Sponsor Name Recipient Name Program Enroll Cnt ISP % PROV Code Code Subtype 280201860934 Academy Charter School 280201860934 Academy Charter School School 435 61.15% CEP 280201860934 Academy Charter School 800000084303 Academy Charter School School 605 61.65% CEP 280201860934 Academy Charter School 280202861142 Academy Charter School-Uniondale Charter School 180 72.22% CEP 331400225751 Ach Tov V'Chesed 331400225751 Ach Tov V'Chesed School 91 90.11% CEP 333200860906 Achievement First Bushwick Charte 331300860902 Achievement First Endeavor Charter School 805 54.16% CEP 333200860906 Achievement First Bushwick Charte 800000086469 Achievement First University Prep Charter School 380 54.21% CEP 333200860906 Achievement First Bushwick Charte 332300860912 Achievement First Brownsville Charte Charter School 801 60.92% CEP 333200860906 Achievement First Bushwick Charte 333200860906 Achievement First Bushwick Charter School 393 62.34% CEP 570101040000 Addison CSD 570101040001 Tuscarora Elementary School School 455 46.37% CEP 410401060000 Adirondack CSD 410401060002 West Leyden Elementary School School 139 40.29% None 080101040000 Afton CSD 080101040002 Afton Elementary School School 545 41.65% CEP 332100227202 Ahi Ezer Yeshiva 332100227202 Ahi Ezer Yeshiva BJE Affiliated School 169 71.01% CEP 331500629812 Al Madrasa Al Islamiya 331500629812 Al Madrasa Al Islamiya School 140 68.57% None 010100010000 Albany City SD 010100010023 Albany School Of Humanities School 554 46.75% CEP 010100010000 Albany -

NYC Schools That Are Identified As Being in Improvement Status

School Accountability Status For The 2007-08 School Year Based On Assessment Results For The 2006-07 School Year New York City Schools Schools that are identified as being in improvement status County/District/School 2007-08 School Year Status Subject County: NYC CENTRAL OFFICE N Y C Alternative Hs District BRONX REGIONAL HIGH SCHOOL In Corrective Action Secondary-Level English Language Arts Secondary-Level Mathematics CASCADE HS FOR TEACHING AND LEAR In Corrective Action Secondary-Level English Language Arts CROTONA ACADEMY HIGH SCHOOL In Need of Improvement - Secondary-Level Mathematics Year 2 EDWARD A REYNOLDS WEST SIDE HS In Need of Improvement - Secondary-Level English Language Arts Year 2 Secondary-Level Mathematics HS 560M-CITY-AS-SCHOOL Requiring Academic Secondary-Level English Language Arts Progress - Year 2 LIBERTY HIGH SCH ACAD-NEWCOMERS In Need of Improvement - Secondary-Level English Language Arts Year 1 Secondary-Level Mathematics LOWER EAST SIDE PREP SCHOOL In Need of Improvement - Secondary-Level English Language Arts Year 1 PULSE HIGH SCHOOL In Need of Improvement - Secondary-Level English Language Arts Year 1 Secondary-Level Mathematics QUEENS ACADEMY HIGH SCHOOL In Need of Improvement - Secondary-Level Mathematics Year 1 SATELLITE ACADEMY HIGH SCHOOL Restructuring - Year 1 Secondary-Level English Language Arts County: MANHATTAN Charter Schools JOHN V LINDSAY WILDCAT ACAD CHART In Need of Improvement - Secondary-Level English Language Arts Year 2 Secondary-Level Mathematics New York City Geographic District # 1 MARTE -

2014 Resource Guide Middle School Portfolio Preparation 2014

2014 Resource Guide Middle School Portfolio Preparation 2014 ART EDUCATION PROGRAM MIDDLE SCHOOL PORTFOLIO PREPARATION Contents Program Overview 1 Calendars 2 NYC Public High Schools with Art Programs 3 Audition vs Admissions Process 4 How to Prepare for your Visual Arts Audition 5 Specialized Art High School Guidelines 7 FAQ: Frequently Asked Questions 9 Portfolio Building Tips 10 Artwork Matting and Label Samples 11 What happens if I don’t get accepted? 12 Middle School Portfolio Development Programs 12 Art Materials and Stores in NYC 13 Resources on the Web 14 Middle School Portfolio Samples 16 3 ART EDUCATION PROGRAM MIDDLE SCHOOL PORTFOLIO PREPARATION Program Overview PROGRAM GOALS WORKSHOPS CONSIST OF... » Provide families with the information and support to apply to A family orientation to give an overview of the schools that are the NYC Specialized Art High Schools classified as Specialized Visual Art programs. » Build students communication and confidence through Hands-on art making experiences to support portfolio group discussions and individual interview exercises requirements » Assist students in developing strong observational drawings that reflect their understanding of the basic elements of art Inquiry-based discussions and activities in museum galleries and principles of design Individual portfolio reviews and interview skills assessment » Provide students with individualized assessments of their Presentations on portfolio preparation and organization current portfolios » Provide and encourage a framework for students -

ACE Mentor Program of Greater NY Participating Schools 2019-20

ACE Mentor Program of Greater NY Participating Schools 2019-20 A.Phillip Randolph Campus High School Channel View School for Research Hendrick Hudson High School Abraham Clark High School Chelsea CTE High School High School for Construction Trades, Engineering, Abraham Lincoln High School Church of God Christian Academy and Architecture Academy of American Studies City College Academy of the Arts High School for Contemporary Arts Academy of Finance and Enterprises City Polytechnic High School of Engineering, High School for Environmental Studies Academy of Urban Planning and Engineering Architecture, and Technology High School for Health Professions and Human All City Leadership Academy Civic Leadership Academy Services All Hallows High School Clarkstown High School North High School for Math, Science and Engineering and All Hallows Institute Clarkstown High School South City College of NY Archbishop Molloy High School Cold Spring Harbor High School High School of Arts and Technology Archbishop Stepinac High School College of Staten Island High School for High School of Computers and Technology Art & Design High School International Studies High School of Economics and Finance Avenues: The World School Columbia Secondary School for Math, Science, and High School of Telecommunications Arts and Aviation High School Engineering Technology Baldwin Senior High School Community Health Academy of the Heights Hillcrest High School Bard High School Early College Manhattan Cristo Rey New York High School Hillside Arts and Letters Academy Bard High School Early College Queens Croton Harmon High School Holy Cross High School Baruch College Campus Curtis High School Holy Trinity Diocesan High School Bayside High school Davis Renov Stahler Yeshiva High School Horace Greeley High School Beacon School Democracy Prep Charter High School Horace Mann School Bedford Academy High School Digital Tech High School Humanities Prep High School Benjamin Banneker Academy Dix Hills High School West Hunter College High School Benjamin N. -

Committee on City Healthcare Services: 2018 Report

Committee on City Healthcare Services: 2018 Report October 2018 0 Contents Introduction .................................................................................................................................................. 2 Background and Context ............................................................................................................................... 2 Health Data Summary ................................................................................................................................... 4 Summary of City Healthcare Services ......................................................................................................... 12 Administration for Children’s Services .................................................................................................... 12 Human Resources Administration (Department of Social Services) ....................................................... 13 Department of Homeless Services (Department of Social Services) ...................................................... 15 Department for the Aging ....................................................................................................................... 16 Department of Health and Mental Hygiene ........................................................................................... 18 Department of Education ....................................................................................................................... 20 NYC Health + Hospitals........................................................................................................................... -

Judge's Victims

Including The Bensonhurst Paper Published weekly by Brooklyn Paper Publications Inc, 26 Court St., Brooklyn, NY 11242 Phone 718-834-9350 AD fax 718-834-1713 • NEWS fax 718-834-9278 © 2003 Brooklyn Paper Publications Inc. • 14 pages • Vol.26, No. 27 BRG • July 7, 2003 • FREE Cyclones write a check Judge’s City audit: Brooklyn, SI Clones take 3 teams owed big bucks from SI Yanks By Gersh Kuntzman In the Cyclones’ case, the team for The Brooklyn Papers failed to pay the city its share of By Vince DiMiceli victims rent it collects from retail estab- Apparently, the sweetheart lishments on the Surf Avenue side The Brooklyn Papers deals weren’t sweet enough. of Keyspan Park, the $40 million While the Yankees have dominated Women paying Both the Brooklyn Cyclones and beachfront edifice that the city the Mets during inter-league play this the Staten Island Yankees — teams built for the Cyclones’ exclusive year, the fortunes have been flipped that don’t pay rent on their city-built use. The retail spaces are current- down in the minor leagues. price in scandal facilities if their attendance falters ly occupied by a bar and a pizze- The Brooklyn Cyclones, a New York — have cooked the books to ensure ria. The city share of the rent is Mets affiliate, continued their domination of By Deborah Kolben that they pay even less to the city, $49,300. the Staten Island Yankees this week with The Brooklyn Papers two new reports show. The team also failed to pay wins Monday and Wednesday nights at Brooklyn Supreme Court In separate audits issued this $50,000 into a reserve fund for Keyspan Park and Tuesday night across the Judge Gerald Garson has been week, city Comptroller William future renovations or improve- Narrows — giving them six victories Thompson found that both the ments at Keyspan Park, a require- accused of turning his judge’s against the Baby Bombers in six tries this chambers into a marketplace 2001 New York-Penn League ment of the lease. -

2020 Nyc 2020 High School Admissions

2020 NYC HIGH SCHOOL ADMISSIONS GUIDE 2020 NYC HIGH SCHOOL ADMISSIONS GUIDE MySchools.nyc Explore. Choose. Apply. Visit MySchools ( MySchools.nyc) to explore your high school options from your computer or phone, choose programs for your personalized application, and apply—all in one place. Year-round, you can use MySchools to: 0 Search an interactive high school directory for programs by name, location, accessibility, interest areas, academic off erings, activities, sports, and more! 0 Explore programs across the city. During the high school application period, you can also use MySchools to: 0 Access your personalized high school application—your school counselor will tell you how. 0 Save your favorite schools and programs. 0 Schedule your specialized high schools admissions test (SHSAT) or LaGuardia High School audition by early October. 0 Add 12 programs to your high school application. Place them in your order of preference, with your fi rst choice at the top as #1. 0 Apply by the deadline, December 2, 2019. Be sure to click the “Submit Application” button. We’re here to help! If you need support with MySchools or have questions about high school admissions: 0 Talk to your school counselor. 0 Call us at 718-935-2009. 0 Visit a Family Welcome Center—locations are listed on the inside back cover of this guide. ABOUT THE COVER Student: Nova Stanley | Teacher: Carl Landegger | Principal: Manuel Ureña Each year, the NYC Department of Education and Cooper Hewitt, Smithsonian Design Museum partner on a cover design challenge for public high school students. This book’s cover was designed by Nova Stanley, a student at High School of Art and Design. -

Just a Nosh..Just Just a Nosh..Just John Ossoff, Left and Distorted Image

St. Petersburg, FL 33707 St. Petersburg, FL Avenue 6416 Central Tampa Jewish Press of Inc. Bay, Tampa The Jewish Press Group of www.jewishpresstampa.com VOL.33, NO. 2 TAMPA, FLORIDA A AUGUST 7 - 20, 2020 12 PAGES Hillel Academy to open Aug. 12 with new safety The Jewish Press Group U.S. POSTAGE PAID U.S. POSTAGE of Tampa Bay, Inc. Bay, Tampa of PRESORTED measures in place STANDARD By RACHEL FREEMAN Jewish Press Hillel Academy in Tampa is planning to re- open with in-person classes on Wednesday, Aug. 12 with a number of new health and safe- ty procedures in place to protect students and staff. Head of School Allison Oakes said that Hillel JustJust Compliedaa nosh..fromnosh.. JTA news service Academy, and most other private schools in the Jeff Halpern is an assistant coach with the Tampa Bay Lightning, which resumed play Aug. 3. area, are reopening as scheduled because they can change “environmental factors” more eas- ily. She attributed the two-week delay in open- Meet Jeff Halpern, a Lightning ing public schools to a lack of time spent plan- ning for the school year amid the COVID-19 coach and Jewish sports honoree pandemic while Hillel has been prepping since By BRUCE LOWITT as an assistant coach with the Tampa early June. Jewish Press Bay Lightning following 14 seasons as In an effort to alleviate potential fears about It was Wednesday night, Oct. 12, 2005, a player in the National Hockey League, the return to classes during a pandemic, a pan- and the Washington Capitals were suit- including two with the Lightning. -

Copy of Fall 2019 Data Pages 4 to End Incomplete SS.Xlsx

Enrollment Report Fall 2019 Office of Institutional Research Fall 2019 Enrollment Report Table of Contents Key Findings 3 Fall 2019 College Enrollment Summary 4 Graduate Student Profile 5 Fall 2019 Graduate Student Enrollment Summary 6 Applied, Accepted & Enrolled for Fall 2019, First‐Time Graduate Students 7 Graduate Applicants and Enrolled Student’s Most Recent Prior College 8 Graduate Enrollment at SUNY Campuses 9 Undergraduate Student Profile 10 Fall 2019 Undergraduate Enrollment Summary 11 Undergraduate Student Body by Gender, Permanent Residence and Age 2010‐2019 12 County of Permanent Residence, Fall 2019 Undergraduate Students 13 Distribution of Undergraduate Student Enrollment by Ethnicity Fall 2015‐2019 14 Applied, Accepted & Enrolled for Fall 2017 to Fall 2019, First‐Time Students 15 Applied, Accepted & Enrolled for Fall 2017 to Fall 2019, Transfer Students 16 Applied, Accepted & Enrolled for Fall 2017 to Fall 2019, Transfer & First‐Time Combined 17 Undergraduate Enrollment at SUNY Campuses 18 Undergraduate Enrollment by Student Type and Primary Major 19 Undergraduate Enrollment by Curriculum 2010 to 2019 20 New Transfer Students by Curriculum Fall 2015 to Fall 2019 21 New Freshmen Selectivity 22 Top 50 Feeder High Schools by Number of Students Registered 23 Top 50 Feeder High Schools by Number of Students Accepted 24 Alphabetical Listing of Feeder High Schools 25 Most Recent Prior Colleges of Transfer Applicants Sorted by Number Registered 49 New Transfer Students Most Recent Prior College 57 Fall 2019 Enrollment Report Key Findings Graduate Students Enrollment in the Master of Science in Technology Management program remained steady at 57 students in Fall 2019 compared to 54 in Fall 2018. -

'Look Both Ways'

PAGE 7-13 Including The Bensonhurst Paper Japan is in season Published every Saturday by Brooklyn Paper Publications Inc, 55 Washington Street, Suite 624, Brooklyn NY 11201. Phone 718-834-9350 • www.BrooklynPapers.com • © 2004 Brooklyn Paper Publications • 16 pages including GO BROOKLYN • Vol.27, No.5 BRZ • February 7, 2004 • FREE Gentile ‘SOB Marty’ comment brings hush to BRCC luncheon By Jotham Sederstrom A laughing Golden, who hosted the lunch- ton High School. Along the way, the coun- The Brooklyn Papers eon at his 76th Street catering hall, came up to cil has organized political, public and Gentile after and shook his hand. school board forums. Touting Brooklyn as a 2012 Olym- As always, the luncheon attracted Bay “Many organizations together can roar,” pic destination and home to future Ridge’s most active community board mem- said Sacco. national conventions, both Democratic bers, religious leaders, business owners, and Praising the council for “making Brook- and Republican, Borough President elected and appointed officials. Between bites lyn, Brooklyn,” Markowitz named Jan. 31 Marty Markowitz roundly praised of chicken or salmon, the audience applauded “Annual Luncheon Day in Bay Ridge,” a plans to build a professional basketball Ilene Sacco, chairwoman of the Bay Ridge similar honor to the one he bestowed last arena in the Downtown area for the Community Council (BRCC), who spoke of year, when he declared Feb. 1 as Bay Ridge National Basketball Association Nets, the past year’s successes and failures. Community Council Day. during his address at the Bay Ridge “We’ve won some and we’ve lost some,” Markowitz, whose idea it was to lure a Community Council’s annual Pres- said Sacco. -

Financial Aid Contact: Thursday, Oct.17Th 5Pm – 8Pm 3787 Bedford Ave

NEED HELP WITH FAFSA? Helpful Contact ATTEND AN EVENT BELOW Information Please remember to bring your family’s 2018 Tax Returns, Parents & Student’s FINANCIAL Social Security #’s (if applicable) For general issues/questions about Madison High School applying for financial aid contact: Thursday, Oct.17th 5pm – 8pm 3787 Bedford Ave. Brooklyn, NY 11229 FAFSA Hotline: 1-800-433-3243 AID Midwood High School TAP Hotline: 1-888-697-4372 Tuesday, Oct. 29th 5pm – 8 pm 2839 Bedford Ave. Brooklyn, NY 11210 For questions related to CUNY New Utrecht High School Colleges admission or financial aid, 101 Thursday, Nov. 7th 5pm-8pm 1601 80th St. Brooklyn, NY 11214 contact the following numbers below SUNY Downstate Medical Center CUNY COLLEGE ADMISSIONS FINANCIAL AID Saturday, Nov. 9th at 11am-2pm 395 Lenox Ave, Brooklyn, NY 11203 Baruch College 646-312-1400 646-312-1360 *RSVP REQUIRED* BMCC 212-220-1265 212-220-1430 Fashion Institute of Technology Brooklyn College 718-951-5001 718-951-5051 Saturday, Nov. 9th at 9am-1pm Seventh Ave. at 27th St, NY, NY 10001 City College 212-650-6977 212-650-5819 *RSVP REQUIRED* CSI 718-982-2010 718-982-2030 SUNY Welcome Center Monday, Nov. 4th at 6:30pm-8:30pm Guttman CC 646-313-8010 646-313-8011 33 W 42nd St New York, NY, 10036 *RSVP REQUIRED* Hunter College 212-772-4490 212-772-4820 SUNY Welcome Center John Jay 212-564-6529 212-237-8149 Monday, Nov. 18th at 6:30pm-8:30pm 33 W 42nd St New York, NY, 10036 Kingsborough CC 718-368-4600 718-368-4644 *RSVP REQUIRED* Laguardia CC 718-482-5000 718-482-7218 SUNY Welcome Center Medgar Evers 718-270-6024 718-270-6141 Monday, Nov.